Victoria’s House of Horrors

*Here’s a sample article of what you will find when you become a British Columbia Chronicles Subscriber!

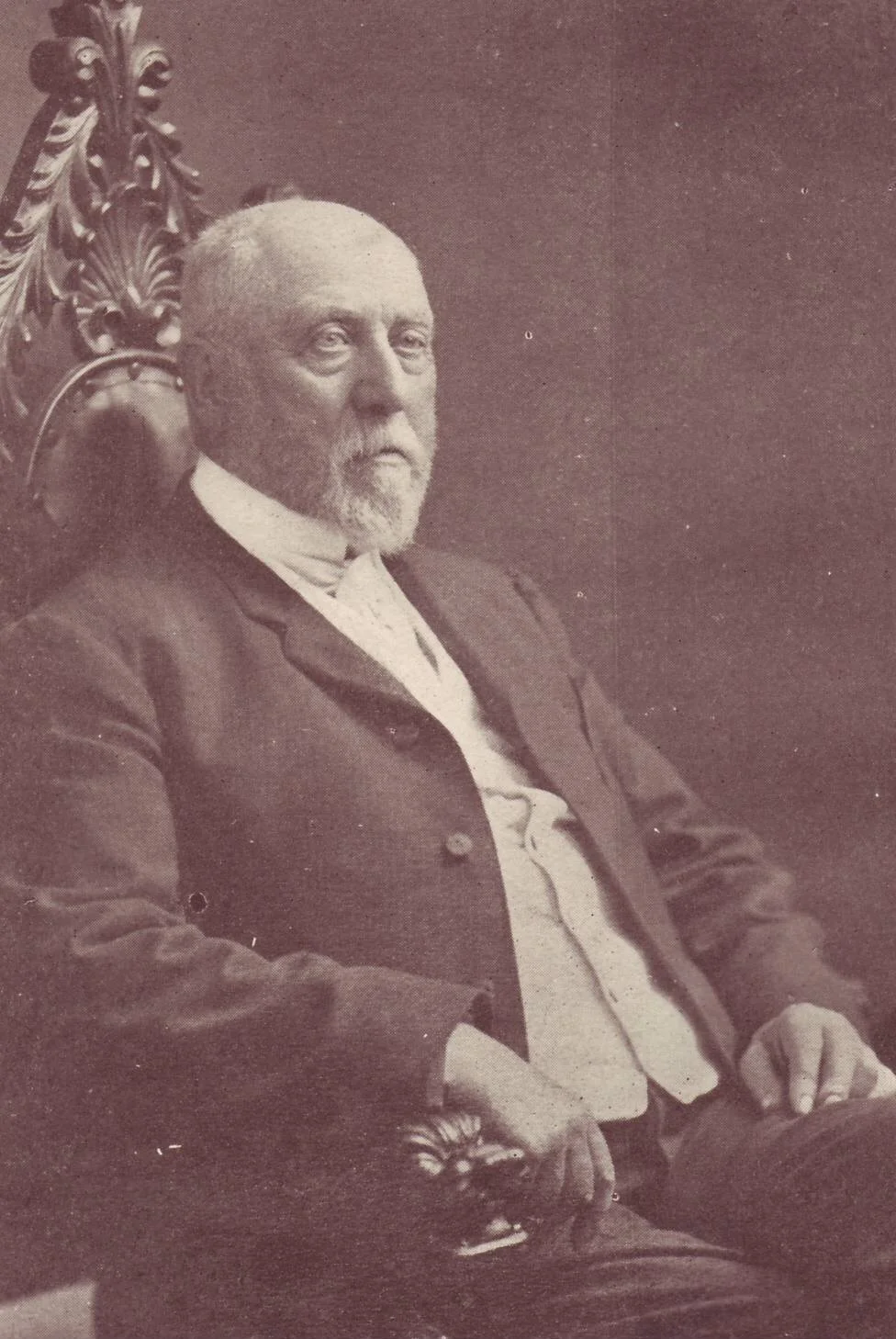

D.W. Higgins

This grisly tale of Victoria’s ‘Pest House’ was originally set down in print more than a century ago by Victoria journalist and politician D.W. Higgins. By then Higgins, who’d come to B.C. for the Fraser River gold rush, was retired and enjoying the role of raconteur in a weekly article in the Colonist.

Lord knows, he had lots to choose from. There had hardly been an event of consequence over the previous 50 years nor a man nor woman who made the news with whom Higgins made no claim to having had, at the very least, a passing acquaintanceship.

His two books, The Mystic Spring and The Passing of a Race, compiled of his Colonist articles, are without equal for their colour and their flat-out entertainment value. Which makes them highly collectible, and which makes some historians take issue with Higgins’ exact reconstruction of conversations and events.

His repeated claim to have had an inside track does make one marvel how any one man could have been in the right place at the right time so often.

Victoria Harbour.

But all of this is an aside. As a storyteller, Higgins is one of the best and your Chronicler has unabashedly resurrected many of his classic tales in recent years. My interest in today’s drama, however, comes from a different quarter, my own research into a double murder on San Juan Island. A murder that, it turns out, was pre-staged in Victoria. Without Higgins, it’s unlikely that a later researcher such as myself would have been able to make the connection between Victoria’s so-called Pest House for quarantine patients and the Dwyer tragedy. Higgins saw the link because he was in the midst of it as a journalist. Bless him for telling us about it 50 years later...

He began by explaining how, in the early 1860s, it was rumoured that “a strip of land lying along the line of Dallas Road, south of Beacon Hill Park, was not included in the acreage re-conveyed to the Imperial Government by the Hudson’s Bay Company at the time Vancouver [Island] was created a colony, and that the strip in question was open to pre-emption. Several enterprising persons took advantage of the information and settled on the land. Amongst others a former Speaker (of the House), Dr. Trimble, and Geo. E. Nias, a publisher, impressed with the idea that there was something in the report, erected habitations thereon, after trying to record the claims at the lands and works office.

“Dr. Trimble had a small shanty erected and sent a man to reside in it; but Nias built quite a substantial cottage and a cow-shed and stable, fenced in the land to which he laid claim, and went there to reside with his family. The case came before the courts and was partially heard, and after one or two adjournments Dr. Trimble dropped out, and there remained only Nias to be dealt with. He held onto his ‘rights’ with true British fortitude, and continued to reside there under the belief that possession was nine points of the law. Neither the strip nor Beacon Hill park was then included in the corporate limits of Victoria city, and I cannot remember that any steps were taken to dispossess Nias by the Government.

I only know that he went away to Australia some years later.

“When his family moved off the land I do not know, but in 1871 the buildings were vacant, the doors swung wildly on their hinges, and the wind rioted through the broken windows, the panes of which had been broken by mischievous boys. Soon the house fell into a condition of dilapidation and disrepair, and if there are such things as ghosts and hobgoblins they must have had a gay old time disporting in the empty rooms and playing hide-and-go-seek through the stables and sheds. The strip presently began to be regarded as a sort of No Man’s Land, and the Nias homestead as belonging to anyone who might wish to occupy it.”

The issue of occupancy became one of expediency in 1872 when the San Francisco mail steamship Prince Alfred “crawled into Royal Roads with her ensign set at half-mast and the yellow flag flying” that warned of contagion on board. A young female passenger had been diagnosed with smallpox and the ship was quarantined.

As were the 75 passengers who were landed at Macaulay Point and placed under armed guard. For weeks, food, mail, newspapers and gifts could be taken in but no one could leave until it was determined that none were infected. Not that they seem to have suffered unduly, Higgins noting that “every necessity and luxury, including ice-cream and strawberries, and the best of wines, liquors and cigars,” were provided for them.

Which was considerably more than could be done for five-year-old Bertha Whitney.

She was confined with her parents, the Alfred’s second officer (because he’d carried her ashore) and a ship’s steward who also showed signs of the disease, in the abandoned Nias house at Holland Point which had been requisitioned for use as a “pest house,” the term then used for a place of quarantine. Shortly thereafter, the girl died and was buried in the immediate vicinity, beside today’s Dallas Road. Although her exact grave site isn’t known a granite marker memorializes “Bertha E. Whitney, age 5 years, passenger on the steamship Prince Alfred inbound from San Francisco who died of small pox June 23, 1872. Other unknown victims were also buried here. The pest house stood nearby on Dallas Road."

“When, six weeks later, the quarantine was lifted, she was the only fatality and Nias’s old house was again abandoned to “the rats and bats and owls and hobgoblins... And so it remained, forlorn and tumbling gradually to pieces [until] the mysterious and tragic incident I am about to relate directed renewed attention to it,” Higgins penned in 1904.

The second part of our story began on the 28th of November, 1872, when a respectably attired man registered at Victoria’s Angel Hotel as “P. Locker, San Francisco.” He said he’d just arrived by steamer and intended remaining for some time. Assigned a room, he came and went as did most of the other guests, seeming to be without employment or other visible business interests.

The plot thickens...

Locker kept to himself but, Higgins tells us, he “had the air of a person upon whose mind rested a heavy weight, either of guilt or fear. When at the dining table he would always sit so that he commanded a view of the front or entrance door, and narrowly watched every person who might enter. Being a good checker-player, he was very much in demand at the tables, but it was remarked that he never would play except with his face turned towards the door.”

Locker attended church morning and evening each Sunday and sometimes dropped out of sight for four or five days while retaining his room in the Angel. Come Monday morning, he’d reappear at the office to pay his bill in advance. “Taken altogether, Locker was a model boarder,” in Higgins’s view, “but he was not very communicative, and on no occasion volunteered any information about himself, beyond that he was a native of Scotland and had lived in New Brunswick. To one man he said he was a landscape gardener. On another occasion he described himself as an architect, and again as a merchant. His object in giving these various descriptions of himself was probably to destroy all trace as to his identity.”

Shortly into 1873, Locker mentioned to a fellow guest that he was expecting his wife from the East and that he’d decided to settle in Victoria. Did the guest know of a good house available? The man, as a joke, directed him to the abandoned Nias place on Dallas Road. Much to his surprise, however, Locker later told him after that he was planning to rent it for a year after doing some repairs. When informed that it had been used as a pest house for smallpox patients, that a girl had died there, he said he didn’t care; he’d had the pox and his wife wouldn’t fear it, either.

Higgins continued: “After that Locker made many visits to the pest house.

“He was seen sitting in the stable reading a book, he was seen examining the dwelling, and on one occasion he was observed mending a fence with hammer and nails... One day a young man, known as Rufus, who had boarded at the Angel, reported that he had seen Locker standing near the pest house talking earnestly with a tall woman. As he neared them, the pair ceased to converse, and turned their eyes seaward. Rufus touched his hat as he passed, and Locker bowed in return. Rufus continued that he had placed about [300] feet between himself and the others when he heard an exclamation, and turning quickly, saw the woman strike Locker in the face.”

Locker seized her hands and held her until Rufus, minding his own business, hurried on. That evening, Locker took his accustomed seat at the hotel table with his face turned towards the door as usual. Across his cheek and nose Rufus saw a red welt “as if made with a stick or whip”. Locker was even less communicative than usual and retired early.

For two days and nights he was away, not returning until the third day to pay his bill and resume his checkers. Although Rufus had told other hotel guests of the scene he’d witnessed between Locker and the woman, no one broached Locker on the subject and he said nothing. “Whoever or whatever else she was,” wrote Higgins, “the woman was never seen again by mortal eye in or near Victoria. If she was Locker’s wife, he never mentioned the fact to anyone, nor did he ever speak again of his intention to occupy the pest or any other house. Gradually the occurrence faded from men’s minds, and Locker came and went as before, unquestioned and disregarded.”

On a mid-February afternoon about a month after Rufus witnessed the scene near the pest house, a man walking along the Dallas road casually looked into the Nias stable. He was startled to discover a man’s dead body lying on the floor near one of the stalls. He’d been shot through the head, the ball entering the centre of the forehead and lodging, as was afterwards determined, in the brain. As no pistol lay near the corpse, it was instantly suspected that he’d been murdered. The body was taken to the Bastion Square Police Barracks to be exhibited “in all its ghastliness” for the purpose of identification.

Several of the boarders at the Angel thought the body resembled that of Locker.

He hadn’t been seen since the day before its discovery, although the corpse was clothed in a ragged coat, a coarse shirt, patched trousers, and shoes, unlike Locker’s usual neat and respectable attire, and, nearby, lay a dirty old hat. There was no vest, and the watch Locker was known to have carried was not found. Although the body at the police barracks wasn’t identified, when police examined Locker’s hotel room they found a pencilled note which read, “I give the landlord everything.—P. Locker.”

According to Higgins this discovery only fuelled the mystery even though it was now generally accepted that the corpse was that of Locker: “If it was a case of suicide, where was the pistol? How did the corpse come to be clad in such indifferent garments, for when last seen Locker wore good clothes? Who was the strange woman with whom Locker had had the altercation four weeks before?” Not until 40 years later did journalist D.W Higgins connect the dots.

At first the police were baffled.

The mystery of the body found at the former pest house with a bullet in the head and thought to be that of P. Locker, likely would have gone unresolved but “for an accidental discovery”. A day after the body was found, a native youth appeared at a second-hand store. He wanted to sell a pistol. The dealer, unsatisfied with the boy’s story of how he came into possession of the weapon, held him until police could be notified.

Their interrogation led them to a hut where another pistol and a quantity of clothing were found. The occupants, having been placed under arrest, claimed that two others, Joe and Charley, had found a man lying dead in the stable with a pistol at his side. They’d taken the gun and Charley had exchanged clothes and shoes with the dead man. When arrested, Charley was wearing Locker’s trousers, coat, vest and boots.

This didn’t sit well with the coroner’s jury which wasn’t convinced that Locker had committed suicide and returned a verdict that there was no evidence to show by what means, or by whose hands, he met his death. Nevertheless, Joe and Charley were released. The intriguing question of just how the mysterious Locker met his fate, and the whereabouts of the unknown woman with whom he’d been seen arguing, “soon passed from the minds of people thereabouts”.

But that’s not the end of our story by any means. In fact, we’re just warming up!

Two months passed. On a beautiful spring morning while plowing a field on his San Juan Island, former Nova Scotian and Victorian Capt. James Dwyer, 35, was shot dead by two killers bent upon robbery. Mrs. Dwyer, 20 and pregnant, who’d witnessed her husband’s cold blooded murder from her front steps, attempted to bar them from the house but they broke in and shot her, too. When, not killed outright, she pleaded for her life for the sake of her unborn child, one of the slayers “crushed her face and chest with the boots that he wore”.

It later came out in evidence at the trial for the murders of Henry and Selina Dwyer that the accused, Joe and Charley, were the pair who’d stripped the body at the pest house–and that the boots Charley wore when he kicked Mrs. Dwyer to death had been Locker’s boots.

The Dwyers were brought to Victoria, and buried from the Odd Fellow’s Hall “amid the tolling of the church and fire bells,” Charley (Joe having testified for the Crown) was hanged at Port Townsend, Washington Territory, and the pest house was destroyed by fire a year or two later.

All of which should have been the end of the tragic cases of Locker, of the mystery woman with whom he was seen to quarrel outside the pest house, and of the Dwyers.

But not quite. Again, but for the remarkable recall of D.W. Higgins we wouldn’t know that there’s a fascinating sequel. Let’s give him the last word:

“With respect to the tall, dark woman, little or nothing was ever ascertained. The only clue that reached the police was furnished by a householder. He said that a woman, giving the name of Gourlay, applied for and hired a room in his house on the 3rd of January, 1873, paying a month in advance. She did her own cooking in a chafing dish, and all her belongings were contained in a small hand valise.

“The impression of the landlord was that [she] was very poor. She seemed to be an utter stranger and to know no one. When she left her room it was always in the afternoon, and she returned about dusk. She went out one afternoon about a month before Locker’s body was found, and never came back. Her valise, when searched, contained very little of value, and not a single scrap of paper that might show whom she was or where she belonged. The day of her disappearance coincided, as nearly as could be ascertained, with the date on which Rufus saw a woman struggling with Locker on the Dallas Road.”

Forty years after, Higgins drew his own conclusions as to what became of the woman who called herself Gourlay, and why, perhaps, a month after, in a dilapidated stable overlooking windswept Juan de Fuca Strait, the enigmatic Locker had pointed a pistol to his own forehead:

“I often think that some day, should exploration be made near the site of the pest house, that another body [besides that of the smallpox victim], that of a female, will be uncovered.”

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.

Subscribe to The Chronicles

Want to read more articles like this? Subscribe and receive expanded weekly articles, special gifts and more.

Only $24/year (50c a week)!