A Century After, Cariboo Mystery Still Resonates

Conclusion

It’s one of the Cariboo’s greatest mysteries—whatever became of the Halden family, Arthur, Adah and Stanley?

You won’t find headstones or a plot for the Haldens in the Quesnel cemetery because their remains have never been found. Or have they? —BC Archives

According to hired hand David Arthur Clark, they’d left their Quesnel farm by car in October 1920 to attend Arthur’s brother’s funeral in Spokane. But there was no brother in Spokane and they hadn’t returned.

Even Clark’s reference to a car didn’t ring true with B.C. Provincial Police Constable George Greenwood: Quesnel area roads, hardly better than rutted horse-and-buggy tracks, were almost impassable for 1920s automobiles in winter. He’d checked every other means of possible transport, and it would be another year before the Pacific Great Eastern Railway reached Quesnel.

This is downtown Quesnel in 1910, just 10 years before hired man David Clark claimed that the Haldens had left for Spokane by car. Even by 1920, Quesnel was almost cut off from the outside world in the winter. —Pinterest

The last confirmed time that Adah and Stanley had been seen was Oct. 28, 1920, when they’d come to town to stock up on groceries and supplies—a substantial order, all of $120 worth. When the goods were delivered to Grand View Farm, it was the hired hand who received them.

Sadly, as we’ve seen, although Constable Greenwood was convinced of murder, he had to settle for half a loaf by charging Clark with the theft and possession of Adah Halden’s jewellery, for which he was sentenced to two years in the penitentiary. Then Greenwood had him charged with forging a promissory note in the amount of $1250; for this more serious offence, Clark received a 10-year sentence.

Murder was still a hanging offence back then, but a total of 12 years in the Big House was certainly better than Clark getting off Scot-free and, adding insult to injury, gaining possession of the Halden farm. Besides, 12 years had given police ample opportunity to conclude their investigations.

But to no avail. Even hiring Indigenous trackers to examine the property for signs of burial sites, ransacking the Haldane house by tearing into walls and ripping up the basement, searching outbuildings, digging up the ground, sifting the ashes of stump fires and draining the well and creeks, then scouring the back eddies and gravel bars of the nearby Quesnel River, had yielded only three solid clues.

In the ashes of a fireplace, charred and twisted picture frames revealed that Clark had tried to obliterate all personal effects of his employers. What convicted him of forgery was a smudged blotter that, when held up to a mirror, showed how, again and again and again, he’d practised writing Arthur Haldane’s signature.

He needed, he thought, Haldane’s signature for the faked promissory note that would allow him to make a legal claim to Grand View Farm. (Ironically, this was an assumption on Clark’s part—Grand View was in Adah’s name.) Whatever the case, handwriting expert R.J. Sprott convinced the jury that the I.O.U. Clark produced was a phony.

The last, inconclusive but most intriguing clue was found in the ashes of a stump fire or “trampled in the mud in the pig pen,” depending upon which version you prefer. This was an upper dental plate, or teeth, again depending upon your source. All that the investigating police officers ever admitted publicly was that some dentures or teeth had been “sent away” for analysis.

Dentures, of course, are strictly for human use and human teeth can be identified as such but, three-quarters of a century before DNA, linking teeth to either Arthur or Adah Haldane just wasn’t forensically possible. (There’s no mention of police seeking out the senior Haldanes’ dentists or denturists.) The sad fact remains that none of the news accounts of the day offer a followup to dentures or teeth being subjected to scientific analysis and the results.

On May 18, 1928, B.C. Supreme Court Justice D.A. McDonald declared all three Haldens presumed dead. On the assumption that Arthur was the first to be killed, McDonald ruled that he died before Adah. Officially, the dates of death could only be guessed as “some time between Oct. 29, 1920, and February 13, 1927”.

“There is no question a tragedy occurred,” Adah’s brother M.A. Van Roggen told the Vancouver Province. “The bodies were never found. The murderer had three or four months to remove all traces.”

The S.S. Missanabie, the ship on which Adah Halden (as the widowed Adah Wright) and young son Stanley came to Canada from England to settle in Parksvillle, Vancouver Island. There, she met and married carpenter or engineer Arthur Halden, later taking up farming outside of Quesnel.

As the years began to roll by, David Arthur Clark completed his second jail sentence and slipped into oblivion other than for, over the past 90 years, passing references in newspapers, magazine articles, several books, and now online.

In June 1942, a social note in the Cariboo Observer reported that Miss Jacquelyn and Harvey Godfrey of Victoria were passing through Quesnel while on vacation: “The Godfreys are nephew and niece of Mr. and Mrs. Halden, who mysteriously disappeared from their ranch on the top of Dragon Lake hill some years ago. No trace of the missing persons was ever found.”

Thirty years later, in a series of articles about Quesnel pioneers published in the Cariboo Observer, Jenny Dunn recalled interviewing Mrs. Bertha Tingley, former Quesnel mayor, whose husband’s parents and five small children had moved to Quesnel from Prince George in the summer of 1920. Unable to find living quarters immediately, they’d been cordially invited to stay with the Haldens.

(Left) The government building in Quesnel in 1946; from here, in the 1920s, B.C. Provincial Police Constable George Greenwood bent every effort to tie convicted thief and forger David Clark to murder. (Right) An unidentified BCPP constable poses for the camera in Quesnel in 1910.—B.C. Archives

She remembered the family as very friendly, wrote ‘Backwoods Philosopher’ Earl Baity in a 1978 recollection.

According to Mrs. Tingley, her mother-in-law was one of those whom Clark had told the Haldens had left “for the East Coast” in a car that October. “That, Mrs. Tingley figured, considering the condition of the mud roads at that time, and the quality of car tires, was impossible,” noted Baity.

By the time of Earl Baity’s retrospective article the Haldane house, which many had come to believe was haunted, had been demolished. Grand View Farm had been subdivided and so landscaped that the original site of the house was unrecognizable, although not forgotten. Quesnel resident Mrs. Marge McCallum, who remembered it from when she was a girl, said she still got a spooky feeling when she passed by.

Those with long memories experienced their own spooky feeling in 2002 when police, tearing apart Robert Pickton’s pig farm in Chilliwack while looking for human remains, recalled Quesnel’s Haldane horror. “The circumstances were different,” noted the Observer. “There were no prostitutes involved, but when Arthur and Adah Holden went missing in 1920, there was a similar small army of diggers at their Dragon Lake hill property, and the crucial evidence they were looking for could well have ended up suffering a similar gruesome fate...”

“All that was ever found of the Haldens was one upper dental plate. Someone dug it out of an old pig pen.”

In his book, A Walk Back in Time, Quesnel author Jack Nelson recalled visiting the Haldane farm on what’s now Valhalla Road in 1997. By then it was surrounded by new homes and a boarding stable for horses. Despite this development, the actual site of the Halden house that, for years, was thought to be haunted, was still detectable and a single, crumbling outbuilding survived.

“An eerie chill settled over me. Could the Haldens be buried right under where I stood?”

At the time of his last visit to the property, by then situated behind a motel and a restaurant, a crew was excavating for a gas line. He asked them if they’d unearthed anything of interest. “No bones, no harness, hardware, no nothin’. But I am still certain that they [the Haldens] are there!”

* * * * *

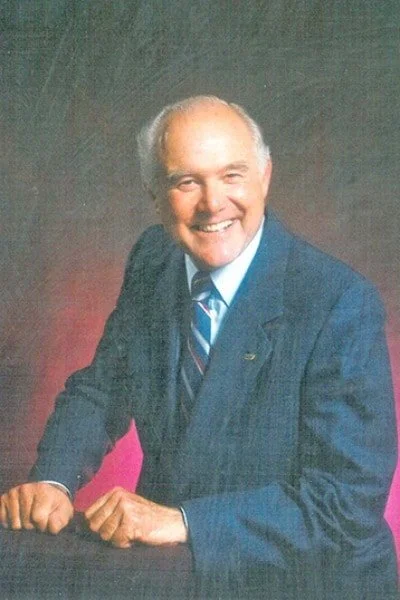

This newspaper photo captures suspected murderer David Clark’s slight smirk. He didn’t look like this after his hunger strike in jail, however. —Cecil Clark

Coincidental to 2003 marking Quesnel’s 150th Anniversary celebrations, Norm Godfrey of Nanaimo, a great nephew of Adah Godfrey, approached council for permission to erect a tombstone for the Haldens in the city cemetery.

“These people were pioneers, and it's a pioneer cemetery,” said Mayor Bellow who supported the idea. Councillor Dalton Hooker disagreed; cemetery markers were put up out of respect to the people buried there; he feared making an exception for the Haldens, who weren’t interred there, could set a precedent.

Councillor Mary Sjostrom thought Godfrey’s proposal “a nice idea” but suggested that “another area” be chosen and Council passed the matter to the Museum Commission for consideration before any decision was made.

Norm Godfrey’s request prompted Cariboo Observer publisher Darcy Wiebe to suggest that Quesnel residents “remember all of our past” by bringing some form of closure to “a disturbing piece of Cariboo history” after 83 long years. After briefly reciting the details of the historic mystery, he pointed out, “There is no memorial to the Haldens in Quesnel, no burial plot. There were no bodies after all. Eventually their farm was sold and then later developed, and no trace remained of the high-profile family...”

Fast-forward 20 years and there is no Halden tombstone in the Quesnel cemetery; instead, a memorial bench was installed in Chuck Beath Memorial Park on Highway 97 near the Quesnel River Bridge. Named in honour of a former Quesnel fire chief, its “picnic tables under an umbrella of Cottonwood and Aspen trees offer a pleasant setting for a meal...[and] serves as a northern entrance point to the Riverfront Trail just a few steps away.”

The bench was unveiled on a Saturday morning in August 2003 at a special 9:30 a.m. ceremony attended by Godfrey and fellow members of the Nanaimo Concert Band. Said to be one of Canada’s largest community bands, they’d detoured by special arrangement from their Barkerville visit to perform in Quesnel.

Publisher Wiebe had encouraged citizens to attend the memorial service even though “there probably aren't a whole lot of people in Quesnel who remember the Haldens, if any.” However, as citizens celebrated their heritage in that special 75th Anniversary year, he thought they “might want to make a point of strolling down to Chuck Beath Park to catch this concert and to help honour a family who remain a part of the fabric of Quesnel's history.

“It's a dark passage, for sure, but one that bears remembering. Let's go out there and make sure that Norm, and cousin Dan Godfrey, who will be flying in from England for the event, know we still remember.”

The 45-minute-long program of music and Halden family history recited by Norm Godfrey was well attended. His second cousin Dan Godfrey and his wife were there, too, having come all the way from Newark, England to lay three red roses on the bench in memory of the vanished Arthur, Adah and Stanley Halden.

The cousins had met just once before at a family reunion in the 1990s. Thanking them for coming, Norm declared it “a symbol of how strong family ties can be”. Later, in a letter to the Observer, he offered his thanks to his 35 fellow members of the band who willingly altered their tour to attend the dedication, and the citizens of Quesnel who helped him organize it:

“The Halden family dedication service was held in Chuck Beath Park on August 3 as planned. The event went extremely well, and I was very pleased with the assistance I received from everyone in Quesnel I approached in the planning of this special event.

“Many people in the audience spoke to me afterwards to express their appreciation for the ceremony I had planned to commemorate the memory of the Halden family. Members of the Nanaimo Concert Band were also very supportive and spoke to me about how moved they were to be part of such an unusual ceremony and what a thoughtful gesture the Godfrey clan was making in dedicating a park bench and plaque in memory of great aunt Adah, her husband Arthur, and adopted son, Stanley.

“The location for the bench couldn't have been better. Chuck Beath Park is a beautiful spot, and I'm sure many folks will find time to sit and take in the view. The plaque will help keep the memory of the Halden Family alive, and the terrible circumstances which surrounded the their disappearance from the Grandview Ranch...”

Had he known earlier that 2003 was the 75th anniversary of the founding of the city of Quesnel, he’d have arranged to have the band perform at the local park as we did in Kamloops and 100 Mile House, while on our way to and from Barkerville...”

He concluded by wishing everyone in Quesnel well and saying he hoped the ongoing softwood lumber problem would be solved before too long, and the forest fire situation quickly brought under control.

* * * * *

Halden family descendant, professional forester and lifelong trumpeter J. Norman Godfrey, who was born eight years after their disappearance, passed away in Nanaimo in 1920.