A Winter Journey in 1861

Part 1

For more than 30 years, respected civil engineer Robert Homfray kept his promise not to publish his account of a dangerous surveying expedition to the Cariboo in 1861.

Finally, in 1894, at the insistence of friends, he agreed to tell of his epic ‘winter journey of 1861’. That was when he and six others had suffered innumerable hardships during an attempt to survey a new, shorter route to the gold fields of the B.C Interior by way of Bute Inlet.

Robert Homfray and party’s assignment: find a shortcut through these mountains from the coast to the Cariboo in the middle of winter!. — https://vancouverisland.com/plan-your-trip/regions-and-towns/coastal-inlets/bute-inlet/

He’d agreed to take charge of the expedition despite the warnings of many who were convinced that he’d never return alive. His friends, in fact, had been quit explicit, arguing that it was “madness to attempt it in the middle of a severe winter”.

They also pointed out “the great danger of navigating the Gulf [sic] of Georgia for so long a distance in a frail canoe, on to the head of Bute Inlet, up an unknown river, and through an unknown country, among mountains covered with snow, surrounded by fierce and savage tribes who had never seen a white man; besides the great risk of being buried under avalanches, attacked by hungry wolves; not to mention the ever-to-be-dreaded grizzly, with the off-chance of perishing miserably in the snow from starvation and exposure... "

As Homfray admitted with a smile so long after, such advice did little to cheer him. but the challenge of “new and strange sights” and the fortunate possession of “a fair amount of courage” were sufficient to over-ride the most strenuous of objections and he looked forward to the adventure.

(Any question as to the secretary of the Philharmonic Society’s courage had been answered several months earlier, when he’d surprised two burglars attempting to break into his home in Trounce Alley. Upon Homfray’s answering their call with a cocked six-shooter, the men had fled into the night.)

Throughout the voyage by canoe to Bute Inlet, Homfray's aide, Cote, would be in command, Homfray acting as ‘Captain’ when ashore. Described as the HBC's best French Canadian voyager, and recognized as an expert with a canoe, Cody brought with him two other voyageurs, Balthazzar and Bourchier, a man named Henry McNeill and two Indians. as they’d be travelling light.

Even as the capital of the Crown Colony of Vancouver Island, Victoria was little more than a scattering of buildings in 1861. By this time the Fraser River gold rush had shifted to the Cariboo.

Their outfit consisted of one canoe, two tents, two muskets and ammunition (a surprisingly small arsenal under the circumstances), and some beads and trinkets for trade. Each man was allotted two blankets, two axes, a hatchet, a spade and a small supply of provisions. Their personal outfits had been kept to a minimum also, as all would have to be backpacked,

When all was ready, they paddled from Fort Victoria on a fair October morning and made good time before putting into shore to camp for the night. Upon getting underway early the next morning, they encountered heavy seas which opened the seams of their canoe and necessitated repairs; a routine of buffeting and patching which would become a ritual by the time you reached Bute Inlet.

After days of paddling against wind and tide, they passed Nanaimo and reached their final camp before crossing the Strait of Georgia. With a night’s rest they prepared to sail, Humphrey noting in his journal that the morning was fine, although the appearance of the Strait was far from encouraging. “When we were nearly halfway across it began to blow, and it looked as if a severe storm would overtake us before we could reach the opposite side....

“Several whales crossed their bow, which frightened us very much. Our canoe was often buried in the waves. However, we finally succeeded in reaching the opposite shore, our canoe leaking badly.”

Nine days from Victoria, the weary adventurous reached Butte Inlet, having survived near-disaster during one violent gale. Here, the wind rushed through the fjord-like inlet with hurricane force and with the terrifying “roar of a cataract”. Adding to this awesome symphony was the continuous rumbling of one avalanche after another as the peaks shed the snowy cakes.

Yet for all of this rugged majesty they weren’t alone as they came upon a party of Indians who were transporting a cargo of dried salmon in four canoes which they’d last together with poles. Immediately upon sighting the strangers, the Natives pulled for shore to land the women and children then paddled in pursuit, muskets levelled.

“Very greatly alarmed,” Homfray instructed his two Indian packers to signal the others not to fire. After several long and tense moments they succeeded in assuring the fishermen that they were peaceable, when the others lowered their muskets and accepted some small peace offerings in the form of some trinkets.

“Next day we saw a large canoe coming directly at us from a dark chasm in the mountains across the inlet, paddling hard. We regarded it with suspicion, and as the canoe came near us, Cote called out to McNeill, ‘Down with the sail! Down with the sail!’

This abrupt command upset one of their Indians; seated behind Homfray, he fired his musket into the air and almost upset the canoe when the others, thinking themselves under attack from the rear, wheeled about.

Within minutes, the strange craft, occupied by six half-naked Indians, all of whom were armed with muskets, came alongside. One of the grim-faced natives boarded their craft and pointed to the “chasm in the mountains from which they had appeared, and made signs to us to paddle hard. None of us spoke but quietly resigned ourselves to certain death.

As we came near to the shore there were deep mutterings among the half-naked Indians, and they picked up their muskets as they were just landing.”

Convinced that they were about to be massacred, the captives waited in silence, when “a war whoop was sounded from across the water, then was repeated several times”. Homfray immediately noticed a change come over their captors who seemed to be undecided as to what to do next and. looking behind him. he saw a tall powerfully-built Indian in a canoe.

Waving his paddle in the air and yelling, the stranger approached rapidly, the prisoners taking advantage of the diversion to stand “shoulder to shoulder on the beach, determined to die together.

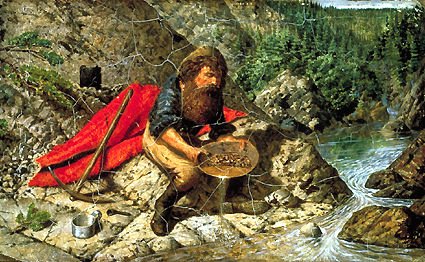

Following the discovery of placer gold in the Thompson and Fraser rivers, the Cariboo became the hot spot for gold mining in the B.C. Interior. But the overland route via Fort Yale was long, tedious and costly for freight and travel. Alfred Waddington was convinced of a shortcut via northern Bute Inlet and it was Robert Homfray and company’s job to survey a route. Attempting to do it in winter in unexplored territory proved to be just short of suicidal. —thecanadianencyclopedia.ca

With both muskets empty, they didn’t stand a chance of escape and waited for the end when, to their amazement and relief, their captors left into their canoe and beat a hasty retreat as the newcomers landed. Introducing himself as chief of the powerful Cla-oosh tribe, he explained that the pirates belong to a distant tribe which made their living by robbing and murdering the occupants of any canoe that fell into their hands.

The gracious chieftain then escorted his guests to the village where, “very weak and exhausted, " they feasted upon mountain sheep, bear and beaver meat. In turn, they made him gifts of trinkets and inquired as to a pass through the mountains. He admitted that there was such a route, but that it was deep in snow and ice at that time of the year and guarded by the ferocious grizzly bear.

Despite their courting with murder, the explorers were eager to push on and applied the chief with gifts and flattery until he agreed to show them the way.

In freezing weather, they proceeded inland. At the head of Butte Inlet, they came upon the debris of an avalanche half a mile wide, and proceeded up the Homathko River. Far in the distance they could see a snow capped peak where, said their guide, the river had cut its way through the mountains.

At a glacier nearby, they dug deep hole as a cache for some of their provisions for the return trip, covering it with logs, dirt and snow. They then headed up river against fierce rapids, two men remaining aboard the frail craft and keeping it off the rocks with poles as the others struggle along the river bank with a towline.

“At last we came to a great single “embassus” formed of drifted logs fallen on top of each other by the winter floods, about 20 feet high and half-a-mile long, stretching across the river.

“The water surged between the logs with great velocity. We had a dangerous task to perform as we had to lift the canoe over [and] into the water on the other side... The logs were very slippery and covered with snow; any misstep would have precipitated us into the raging torrent.. "

Digging a pit in the snow drifts, they pitched their tent inside where they were sheltered from the icy winds which shrieked across the glacier without pause. “The noise of the avalanches falling night and day were deafening. It snowed hard and bear tracks were consistently seen on both sides of the river.”

When they pushed on they found the carcass of a grizzly being devoured by vultures, their progress being watched by black bears and wolves. It was at this point that their saviour and guide urged them to turn back. After consultation, and having decided that “it would show great want of courage if we did not go on," they bade farewell to the chief, who headed downstream, all arguments to make him stay having failed.

Poling and pulling their canoes through the rapids. wading in the icy stream, they virtually wore the clothes from their backs, but still pressed forward, Homfray's log noting the grandeur of the glistening mountaintops, mountain slopes and glaciers.

Time and again, they courted disaster in the rapids but, always, they escaped; at least they didn’t suffer for want of food, the two Indian hunters keeping the expedition well-stocked with mountain sheep, deer and the surprisingly delectable beaver. For that matter, the ever present bear didn’t fare as well, having to rely upon nightly visits to the river in quest of salmon.

"The river was now full of rapids, 13 feet rise in 100 feet, and intensely cold. Then the tow rope snapped, sending the canoe shooting down the rapids like an arrow. We had great difficulty in recovering it. Two men were almost lost, and we found it quite impossible to proceed any further in the canoe.

“We realized too late that we should have followed the Indian chief's advice and turned back with him. We could now see a great canyon in the distance where the river came through the Cascade Mountains, but how we were going to get there we could not say.”

Once again they resoled to push on. After burying their canoe in the snow and tying themselves together like mountain climbers, with sounding poles in hand, they forged the river several times in the course of the day, “as it was so crooked. " Within seconds of leaving the water their drenched clothing was frozen solid, their beards and moustaches also freezing to the point that they couldn't open their mouths to speak.

Now too weak to carry their tent, and carrying only a blanket each and some food, they forced themselves to clamber over boulders which were coated with ice and gave the appearance of enormous glass balls. For mile after mile they struggled over glacier and mountain peak, their strength steadily failing. By this time all were aware of their danger as they must soon become exhausted.

Their only hope, said Cote, lay in encountering some Indians—an ironic turnabout from their arrival at Bute Inlet, when they’d camped without fire so as not too attract the attention of any hostiles.

(To be continued)