A Winter Journey in 1861

Conclusion

For more than 30 years, respected civil engineer Robert Homfray kept his promise not to publish his account of a dangerous surveying expedition in search of a shortcut to the Cariboo in 1861.

Finally, in 1894, at the insistence of friends, he agreed to tell of his epic ‘winter journey of 1861’. That was when he and six others had suffered innumerable hardships and near-death during an attempt to survey a new, shorter route to the gold fields of the B.C Interior by way of Bute Inlet.

Robert Homfray and party’s assignment: find a shortcut through these mountains from the coast to the Cariboo in the middle of winter!. — https://vancouverisland.com/plan-your-trip/regions-and-towns/coastal-inlets/bute-inlet/

* * * * *

Businessman and dreamer Alfred Waddington. —Wikipedia

Note: Victoria businessman Alfred Waddington was convinced that a shorter route to the Cariboo via Bute Inlet could be found via northern Bute Inlet. He it was who sparked the ill-conceived Homfray exploration expedition that almost cost them their lives.

Eventual construction was thwarted by the massacre of a road crew followed by the hanging of several Tsilhoot’in (Chilcotin) chiefs that we know today as the Chilcotin War (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chilcotin_War).

* * * * *

Last week, we saw that Homfray and company, despite having little more than the clothing on their backs, two muskets, few tools and little food, pushed onward, each man watching desperately for the least human sign. But, always, the only reward was yet another view of birds and snow and ice. And so it went, the surveyors labouring forward as their strength diminished until, upon rounding a point of rocks, an overjoyed Homfray spotted a fresh footprint in the snow.

“We kept close together in a single file," he wrote, one musket in front and one in the rear. Suddenly, we saw a tall, powerful Indian and his squaw [sic], standing on the river's edge [and] looking cautiously about, having evidently heard us.

“Despite the cold the brave was almost naked, his body being protected from the frigid wind by no more than a coating of jet-black paint; an appearance made all the more ferocious by large vermilion-coloured rings about his eyes. Immediately upon spotting the strangers, the Indian shielded his wife with his own body and aimed his bow and arrow at them, as he danced up and down and war-who)ped loudly.

At guide Cody's advice, the surveyors rested their heads upon their shoulders to show that they were tired and opened and closed their mouths to indicate they were hungry.

Advancing all the while, they halted within several feet of the wary Native when Homfray, “being not afraid...went slowly up to him. He immediately seized me in his arms, and I was helpless in his powerful embrace.

“Cote ran up, saying, ‘Don't fear, sir, he shan't kill you.’ The Indian then slackened his hold, lifted up my arms, looked into my mouth, examined my ears, to see if I were made like himself. He had evidently never seen a white man before."

Upon satisfying himself that Homfray was indeed "made like himself," the man decided that they were friendly and pointed towards a canyon. After drawing a sketch in the snow with an arrow, he waved them on up-river. They followed his instructions and continued upstream, when several Indians appeared from "different holes in the ground, which startled us very much."

Also armed with bows and arrows, they repeated the first mans’ war dancing and whooping, when one, apparently the chieftain, walked with dignified step towards the explorers. As he neared, covered all the while by his men, he turned and retraced his steps until he came to a bush, when he hung “something of a red colour on a branch."

At this, Homfray and company took heart and moved cautiously forward.

Once again, they were examined from head to foot, then their hosts invited them into their “holes”. At first the visitors were afraid to follow, sure that, once underground, they’d be murdered, but upon realizing that they were no condition to resist, they entered the unusual homes.

However, no sooner had Homfray and Cote entered one of the lodges, the explosion of a musket sent them running outside, Cote yelling that their companions were being slaughtered. Much to their relief, it was another false alarm, their trigger-happy companion having again fired his musket while excited.

Although the shot terrified their hosts, the incident was quickly smoothed over and Homfray and Cote again followed the chieftain “on our hands and knees into the underground den.

“It was a place about 10 feet square and about eight feet deep. When we got inside we saw a very old squaw [sic] and her daughter. They had a small fire burning. When the explorers offered them their last piece of bread their host refused to touch it until Homfray ate a piece to show that it wasn’t poisonous.

The woman, apparently pleased by the gesture, then brought out a wooden bowl which she held up before the fire to see if it were clean. Satisfied, she spit into it several times and wiped it dry with her long, matted hair as an appalled Homfray watched in grim fascination. She filled the dish with some evil smelling concoction as Cote, noticing his discomfort, whispered that they must eat as the food was undoubtedly intended as the woman's finest offering, and to refuse would not only offend her but, quite likely, insult the whole tribe.

Fortunately for the surveyors who, but hours before, had feared starving to death, the woman was almost blind and they were able to slip the contents of the dish to the dogs lying behind them. Smiling broadly, they rubbed their stomachs as a gesture of appreciation and indicate that they wished to sleep. There amenable hosts immediately turned in, unaware that, through the night, at least one of their guests kept watch over the camp.

With morning, Homfray inquired by sign language whether there was a trail through the mountains at that point.

Much to his disappointment, the Indians, by drawing in the snow, explained that the way was blocked for “many suns" by snow and that they should return by the way in which they’d come. They couldn’t ask the explorers to remain with them for the winter as they had barely enough provisions to feed themselves.

So, mourned Homfray, weary and footsore, with their clothes nearly worn out, “we began our homeward journey. We hardly cared what befell us on the way, as it seemed impossible that we could reach the Inlet alive.”

But, somehow, they made it down-river to where they’d hidden their canoe and supplies. Launching the battered craft, they entered the rapids for a swift descent, time and again being threatened with capsizing before they were swept into the wrong channel and swamped, although without injury. Despite this near- miss, Homfray's journal notes, the men weren’t immune to the wonders about them:

“We were fortunate enough to witness a grand sight just after sunrise.

“On the opposite side of the river, nearly a half mile from us, we heard a sharp crash followed by loud rumbling sounds high up on the mountain and in full view. A large avalanche came thundering down with a frightful noise; the whole side of the mountain for fully a mile in length was in motion.

An avalanche in motion.—www.encyclopede.environment.org

“Pine trees went down before it like a swath of mawn [sic grass. It lasted several minutes, the ground sensibly shaking from the violence of the shock which sent enormous masses of rock crashing down into the valley below. As soon as it was over, dense clouds of steamy vapour or rose, caused by the heat from the friction of the immense boulders grinding against each other in their descent.”

Minutes later, they swept around a bend in the river—and into a floating tree.

Impaled on the branch, their canoe filled rapidly, the men having just enough time to clamber onto the trunk and rescue two tents, some blankets, part of a sack of flour, three iron pots, a musket—Homfray’s notebook—their spade, and some matches.

Thus marooned on their "raft," they had no choice but to wait until the tree drifted into the riverbank, when they discovered to their horror that their axes were still in the bow of the submerged canoe. Fortunately, they succeeded in salvaging the precious tools before the bottom of the craft fell out and plunged the rest of their equipment to the river bottom.

“The Indians were crying and beating rocks together, saying they would never see their children again.

“We were very thankful our lives were saved, but what was to become of us now, God only knew. It was a very long way to where the Indians lived on Desolation Sound, perhaps 90 miles further, with no other way of reaching them except by water. With our canoe lost, death seem to stare us in the face..."

Converting their spade into a crude dish, they boiled some water to drink.

They had no tea or coffee with which to give it flavour but it had to do. However, even this seemed to taste good in their loneliness and cold, and, spirits somewhat revived, they decided to build a raft. Chopping down three trees, they tied them together with cedar bark and launched the float. Two of the logs promptly sank, the third being so waterlogged that it would hold only two men.

Cote and one Indian volunteered to go on the raft, Cody saying that the two on the raft might be lost, and those who walked along the bank might be saved. Slowly, painfully, they made their way downstream, wading through the frigid water and clambering over dead-falls that were treacherous with ice.

All the while, they worried that Indians had found their last remaining food cache. Four days later, they found it intact, at which “we quite greatly rejoiced.

“We were now at the head of Bute Inlet, very weak from cold and exposure, our clothes constantly freezing as we waded through the many streams. We were in hopes that we might see some Indians who would take us in their canoes, but there were none to be seen. All our hopes of safety vanished. Our only hope was to cut down a tree, and on it float down the inlets into Destination Sound....”

With the wind blowing at hurricane force and constantly threatening to topple trees onto their camp, the worried explorers readied themselves for the final challenge--when they were attacked by 12 wolves. Returning to their fire, they faced the growling, snapping horde by throwing “fire boards” at them. The wolves finally retreated but this assault, coming on top of all the other hardships, was almost too much to bear.

An attack by wolves was almost the breaking point. —Animal Corner

Two of the men began to cry, further dampening the spirits of the others, and dinner, such as it was, was consumed in silence.

Now on very short allowance, and having lost all of their cutlery in the canoe, they ate with their fingers, taking turns at drinking from their solitary cup, a baking powder tin.

They then started to build another raft. The first two trees they cut, split in half. “The next one the seemed all right. It was 30 feet long. We cut a long hollow in it eight inches wide. It took us 10 days to make it, as we had but two blunt axes to work with.

“We rolled it the short distance to the water, and then nearly every everyone refused to get on it; the men said they would sooner die on land and be drowned. Eventually, however, they were persuaded, and we all got in with our things."

As the log lacked a keel, it tended to roll at the slightest motion; each and every man clinging to it sides painfully aware that, should it turn over, they had not a chance of regaining a hold on its slippery flanks. Several times, the log attempted to capsize and its passengers "expected to go down at any moment”. They rode on without speaking. By following the shoreline, they came to a safe landing place and prepared for the three-mile crossing of the Inlet.

Now reduced to half a bag of flour, a musket, some powder and a few bullets, they made camp and debated their next step. After some discussion it was agreed that Cote and three others (as many as could hope to navigate the Inlet on a log) would proceed to the other side, Homfray and two companions remaining on shore.

Then, convinced that they’d never see each other again, each man shook hands with his companions, and Cote and crew cast off.

After raising their sail, a torn flour sack, they headed to sea. For hours Homfray and companions watched their comrades make steady progress, until they at last vanished in the distance. Cote’s plan was to proceed to Desolation Sound where he’d attempt to induce the Indians to return for the others. If all went well, he’d be back in 10 days.

Today a playground for kayakers and recreationists, Desolation Sound was anything but friendly to the explorers of 1861. —BritishColumbia.com

In the meantime, Homfray's party remained hidden on the beach. worried that they might be spotted by the piratical Natives who’d captured them at the start of their expedition. They constructed a screen of bark and kept a constant watch.

One morning, the lookout sighted a dark spot on the water a long distance off. As Cote hadn’t had sufficient time to get back, the lookout was greatly distressed. “I told him to cheer up and be brave.." said Homfray.

Half an hour passed, the dark form rapidly approaching until they saw it was a large canoe, paddling hard with a tall Indian standing in the bow. “Presently, we heard a loud war whoop sounding across the water... Cold perspiration came over me. Neither of us spoke. A short time later, another war whoop sounded, louder and longer than before. We resigned ourselves to our fate."

Moments later, their agony was ended: it was Cote. After thanking God for their escape, Homfray chided the guide for having frightened them by instructing the chieftain to issue his war cry.Then all returned to the village at Desolation Sound.

After resting and regaining their strength, they headed for Victoria in two canoes with several of the tribesmen. Days later, they crossed the Strait of Georgia in the midst of a squall which almost swamped them, and landed near Nanaimo.

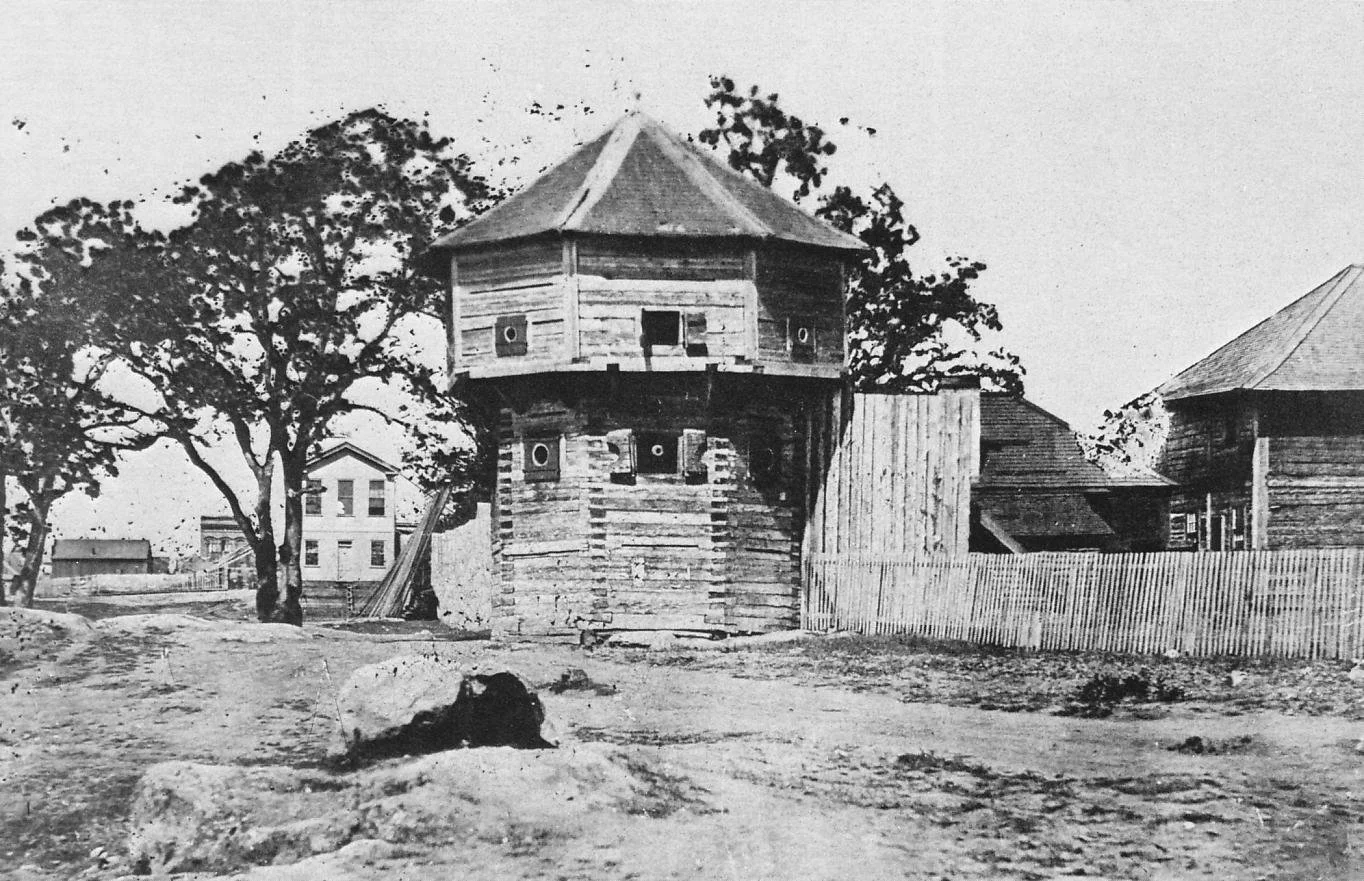

Last stop, Fort Victoria.

Then it was on to Fort Victoria, their considerate guides being astonished, off Cadboro Bay, by the sight of their first cows, a thrill which was forgotten off Beacon Hill when they caught their first glimpse of riders on horseback. Upon landing at the Hudson’s Bay Co. wharf, they were met by company officials and Alfred Waddington who’d prompted their expedition). All expressed amazement at their ragged and half-starved condition.

“The Indians were afraid they were going to be separated from us and would not leave us," Homfray noted. "The company put up a tent for them on the lot where I lived. They would not go outside the fence for a week as they were afraid the other Indians would kill them. At last we persuaded them to visit the HBC Store where the company gave them as many blankets, muskets, etc, as their canoes would carry."

They were then sent partway home by steamer so as to prevent their being robbed and massacred by Southern tribesmen.

And that was that. For 30 years, Robert Humphrey withheld publication of his memorable expedition to Bute Inlet in deference to Waddington who, he said, “feared my descriptions of the many dangers encountered would prevent parties joining him and making the road through to the Cariboo”. This, it should be noted, was long after Waddington’s attempt to build a road through the mountains ended disastrously for the builders and for the local Indigenous people.

Finally, in 1894, Homfray gave his story to posterity. Today’s maps honour this heroic adventurer with a channel, two creeks and two lakes.