Alberni Coroner’s Inquest Was A Farce

In last week’s Chronicle, based upon my first interview as an aspiring young journalist, the late Charles Taylor recounted some of the Alberni Valley’s colourful, often tragic history.

This week, we cut out the middleman and go straight to the horse’s mouth, so to speak...

Scottish-born businessman Gilbert Malcolm Sproat was only 26 when he arrived on Vancouver Island to manage the British-financed Anderson Mill, established in August 1861 at the mouth of the Somass River where Port Alberni now stands. For five years, the company, which acquired almost 1600 acres from the colonial government, operated the first of several sawmills at this site over the next 160-plus years.

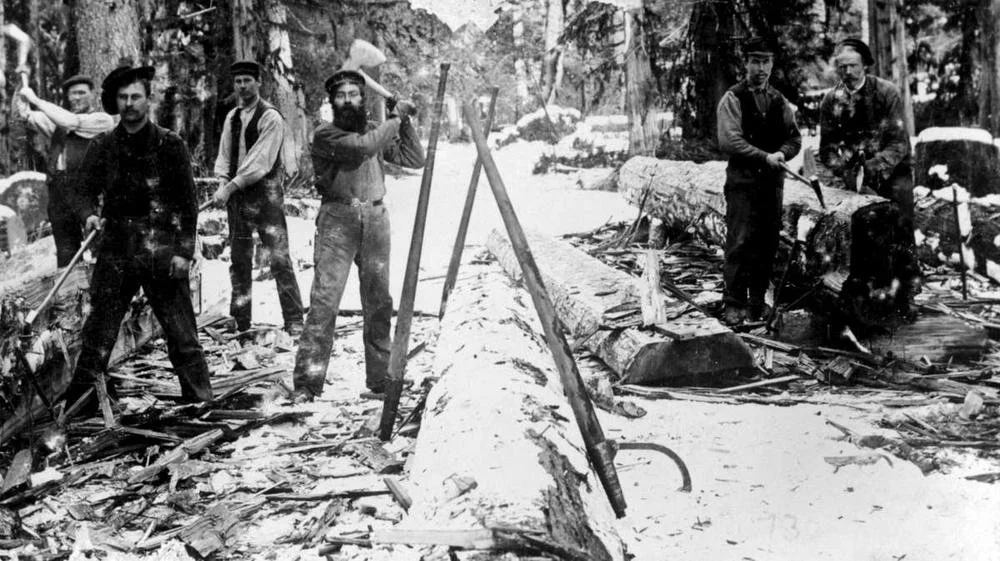

An 1879 sawmill at Alberni; just one of the many which have come and gone in the Valley’s logging history since the early 1860s —BC Archives

As described last week by Mr. Taylor, the company also obtained several hundred acres of good bottom land on the west side of the river. This was cleared and fenced in as a mill farm to grow vegetables and raise livestock, the operation being placed under the charge of an American identified only as Henry.

Mr. Taylor: “Henry planted potatoes in the lower end of the farm, adjacent to the slough that extended in from the harbour, and deep enough to float a canoe at high tide. When the potatoes were about matured and ready for digging, Henry, on looking over his field, discovered a number of rows had been dug and the potatoes removed.

“Nearby, he found marks in the mud where a canoe had landed, and prints of bare feet leading to the vegetable patch. Henry decided to wait for the thieves the following night at high tide. He loaded the musket with dried peas, but probably dropped in a few buckshot, and hid behind some bushes.”

Gilbert Malcolm Sproat, businessman, government officer and author.—Wikipedia

Soon he heard a canoe being stealthily paddled up the slough and landing at the bank. He could make out several figures stealing into the field and beginning to dig. Creeping closer, Henry raised his musket and fired at the nearest figure. The man fell dead over the bag of potatoes he was filling; the others escaped in the darkness.

Henry staggered back to the cabin, dazedly calling to his partner, "Jack, I'm afraid I've shot an Indian [sic].”

* * * * *

This is where company manager Malcolm Sproat, who also served as local magistrate, entered the story. Just a few years later, he recalled the memorable affair in The Nootka: Scenes and Studies of Savage Life, entitling Chapter 11, “An Attempt At Inquest.”

As becomes apparent, his reference to “an attempt” at an inquest is because the only qualified jurors were Henry’s workmates and friends. Objectivity, need it be said, would prove to be in short supply.

(Disclaimer: The author has come to employ First Nations, Indigenous and Native in place of ‘Indian.’ However, when quoting extensively from authors and sources of old, in this case a book published in 1868, conversion becomes unnecessarily problematic.

Please note that the term ‘Indian’ is neither intended to be nor is in fact demeaning, simply the name that was given to native North Americans from the arrival of the first Europeans, five centuries ago, and in general use until recently.)

Sproat’s subhead hints at the content: “Depredations of the Indians - An Indian Shot With Peas - English Staff Surgeon - Soft-hearted Yorkshireman - Absurd Verdicts of the Jury.”

I was roused from my bed one dark, rainy night at Alberni by a messenger from our farm up the Klistachnit River, bringing word that the man in charge of the farm had shot an Indian. The farm was about two miles distant, and being on the opposite side of the river, could not be reached by water. Not knowing very well what to do, I asked Mr. Johnston, a gentleman in our service, to take a few men and go to the farm and see what happened.

Originally, Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia forests were prized for their towering Douglas firs that made excellent ships’ masts. —BC Archives

This party had some difficulty, owing to the darkness, and getting their boat past the drift-trees at the entrance of the rapid stream, but in an hour or two they reached the farm. Two men were employed there—an American and a Yorkshireman—who both were sitting in the kitchen, looking at the fire, when Mr. Johnston entered the house.

It appeared that the foreman, the American, had for several nights past been watching a field of potatoes which the Indians were plundering. They came in numbers up a long creek, and half-filled their canoes in a few hours, and before morning were many miles distant. The foreman, two nights previously, had caught one of these Indians, a fellow who seemed a ringleader, but he had escaped by slipping off his blanket and running naked into the forest.

The same Indian had again returned with his plundering gang on the evening in question. The foreman went out to watch the field, and took with him his gun, loaded with five hard peas, thinking that, if he could not catch an Indian, he would frighten them by shooting the peas among them.

The raiders would half-fill their dugout canoes then escape in the dark—until Henry disturbed them and opened fire. —BC Archives

As usual, the depredators were in the field filling their bags, and as soon as they became aware of the former’s presence, they ran to their canoes. He could not overtake them, but having fired his gun with as good an aim as he could take in the dark at the supposed ringleader, he was horror-struck to see the Indian fall flat upon the ground.

Rushing back to the house with his discharged gun, the foreman cried to his companion, the Yorkshireman, on entering, "Jack I've shot an Indian.”

These particulars being learned, Mr. Johnston and two others took a lantern and visited the field, where, after looking about for some time, they found the Indian lying dead. He had fallen over his potato-bag, and his hands were still clutching the soil. The body was dragged to the river; but the men forming Mr. Johnston's party objected to take it on board the boat, and proposed tying a string around the ankle, and towing the body astern.

Finally, however, a small abandoned canoe was found, and the body was placed in this and towed behind the boat to the settlement, where it was put into a room full of old casks until the morning.

After breakfast next day I proceeded to examine into this affair. The peculiarity of the case was that everybody in the district was in my own employment. I took the word of the American that he would appear when wanted, knowing this to be a better security for his appearance, than locking him up in a room from which he might have escaped.

The feeling among the settlers as to the death of this Indian was that nothing was required to be done. Several men came to me and said, "You're not going to trouble Henry about this—are you, sir?”

Mill manager Sproat found himself having to serve as a justice of the peace to conduct an inquest into the man’s death. He had no experience in legal matters, no one to turn to for instruction, and a reluctant jury. He was on his own!—Pixabay

I could only answer that we must do what the law required us to do. It was easy to summon a jury, but where could we get a doctor to make a post-mortem examination of the Indian's body? The difficulty was solved by a workman advancing from a gang employed in carrying wood, and asking to speak with me. He was a careworn man, dressed in common clothes.

We went into the room that served as an office or court-room, and on entering into conversation, this man told me that he had been a staff surgeon in the British army, and that he had his diploma and the certificates of service in his chest. He brought me these, and they proved the truth of his statement—so, of course, I gladly accepted his services.

The next step was to get a jury.

I selected twelve of the most respectable and intelligent workman, and opened the court: this jury consisted of Canadians, Americans and Englishmen. We inspected the body, and did everything in proper form. The doctor proved that death was caused by wounds in the chest, and he produced a pea, which he had found in the left lung.

The Yorkshireman, who lived in the farmhouse with the American, a fine young fellow about six feet in height, was next examined. He stood in the middle of the room with his cap in his hand, the jurymen standing half-a-dozen on each side of the room. I asked the Yorkshireman to tell the jury what happened that night. He said, his “chum” had gone out of the farm-house, and had come back in about an hour.

He took his gun out and had brought it back. The witness had heard a gun-shot. He knew no more.

I asked this witness what his companion had said when he returned to the house? At this question he blushed, and then grew pale, and twirled his cap round, and said nothing. He seemed embarrassed, and did not reply. Noticing he was ill at ease, I left him alone for a little, and then asked him again the question in a mild tone.

His agitation increased, the cap fell from his hands, he staggered, and finally fainted where he stood. Some of the jurymen caught him in their arms, and carried him outside. I have never seen a strong man faint from mental agitation before or since this occasion; it is probably a very unusual occurrence.

The witness must have had a large heart, and he believed that his evidence as to the words of his companion, "Jack, I've shot an Indian," might be fatal words.

The examination continued, and, after several other witnesses had given testimony, I stated the case to the jury, and sent them into another room for their finding. There was, it appeared, a long debate; for nearly half an hour passed before they returned to my room. One after another entered, and when they had had ranged themselves again on the side of the room, I inquired what their finding was.

The answer was, “We find the Siwash was worried by a dog." [Siwash is Chinook jargon for Indian but is now viewed to be disrespectful.—Ed.]

“A what?” I exclaimed. "Worried by a dog, sir," said another juryman, fearing that the foreman had not spoken clearly.

Assuming, with great difficulty, an expression of proper magisterial gravity, I pointed out to the jury the incompatibility of this finding with the evidence, and went again over the points of the case, calling particular attention to the medical testimony, and the production by the doctor of the pea found in the body of the Indian; after which I, a second time, dismissed the jury to their room, and begged them to come back with something, at all events, reasonably connected with the facts of the case.

A longer time than before elapsed. The jury, on this occasion, left their room, and walked about the settlement, and I saw knots of men conversing eagerly.

There was some hope now, I thought, of a creditable verdict. When the jurymen at length sidled into my room for the second time, I drew a paper towards me to record a finding which I expected would suitably end this unpleasant inquest.

"Now, men, what do you say?” Their decisive answer was, "We say he was killed by falling over a cliff." I shuffled my papers together, and told them that they might go to their work; I would return a verdict for the jury myself.

The farm, I may mention, for a mile every way from where the dead body was found, was level as a table. I could not but think it strange the jury did not decide upon an open or evasive finding, instead of these those extraordinary absurd ones. The fact was the men were determined to shut their eyes, and they shut them so close that they became quite blind.

Not a bit of a joke was in their minds; they acted with perfect seriousness throughout, and this made the comic parts of this tragic-comedy still more ludicrous.

I arrested the American, and sent him in our steamboat to Victoria in charge of a constable, but he escaped from custody. He was an excellent fellow, and I am sure had no intention of killing the Indian. The victim belonged to a distant tribe, but they were too much ashamed of the circumstances of his death to send for the body.

We accordingly buried it in the forest. The Indians who lived beside the settlement were rather pleased than otherwise with the death of this Indian, and many of them pointed to his body and said, “Now you see who steals your potatoes; our tribe does not.”

I beg the reader to observe that the foregoing statement is not in the slightest degree exaggerated or distorted; it is a mere simple statement of the facts of the case as they actually occurred.

So wrote Gilbert Sproat in 1868. Two years later, he wrote Education of the Rural Poor which, according to Wikipedia, “argued for the extension of elementary education to all, including agricultural labourers”. Following Canada’s entry into Confederation in 1871, Sproat served as agent general for B.C. in London for five years. He returned to Victoria then lived in the Kootenays as a government officer for 15 years; upon retirement, he continued to write until his death in 1913.

* * * * *

In conclusion to his telling me the story of the potato patch tragedy, Charles Taylor noted that the local tribe had insisted that, when the man was buried, some potatoes be buried with him “for his long journey”.