Ancient Shipwreck Continues to Haunt Us

More than three-quarters of a century after she sank in B.C.’s remote Grenville Channel, an American army transport is back in the news.

Oil is leaking from the wreck of the S.S. Brigadier General M.G. Zalinski, posing an immediate environmental threat that must be dealt with, according to the Canadian Coast Guard. This, despite the fact that 44,000 litres of heavy oil and 319,000 litres of oily water were extracted from the wreck nine years ago.

The Zalinski, in the foreground, has been underwater since 1946 and has been leaking oil for decades with more feared to come. —www.navsource.org/archives

An estimated 27,000 litres of oil remain within the hulk which sits on a rocky ledge about 27 metres (88 feet) below the surface.

It should come as no surprise that the underwater wreckage 1100 kilometres north of Vancouver is deteriorating as the Zalinski was built way back in 1919. Sadly, she isn’t the only shipwreck that continues to haunt us from the grave.

* * * * *

The Zalinski has, in fact, made more press over the past 20 years than ever she did during her working career; even her dramatic end wasn’t considered to be all that newsworthy. But that was back in a less-enlightened environmental age and times have changed. Look at some of the headlines since 2002:

Storms pull legendary ship’s skeleton from beach grave

Natives on B.C. coast haunted by threat from sunken Second World War ship

Coast Guard to hire divers to patch and inspect wreck off B.C. Coast

Wreck filled with oil and bombs

Oil removal begins on WWII-era shipwreck in B.C.

Canadian Coast Guard announces significant environmental protection operation

For starters, who was her namesake, the real Brig.-Gen. M.G. Zalinski?

According to the NavSource Online Army Ship Photo Archive, Brig.-Gen. Moses Gray Zalinski, U.S. Army (1863-1937) was born in New York, enlisted aged 22 and served in the Artillery, ending up as an assistant quarter-master.

The army transport that would inadvertently immortalize his name had an equally bland career. Five years after she was launched in 1919 as the S.S. Lake Frohna, one of the many ships produced by the United States’ wartime crash shipbuilding program, she was bought by the Ace Steamship Co. and renamed Acer. She retained this name when she was sold again to the Terminals and Transportation Corp. of Duluth, Minn.

Come the Second World War and another crying need for shipping, she returned to government service as an army transport in 1941. This time she was assigned the name she’d carry to the grave: S.S. Brig-Gen. M.G. Zalinski, for the career artilleryman/quarter-master.

It was in the role of an army transport that the Zalinski found herself in B.C. waters, late in September 1946, while en route from Seattle to Whittier, Alaska, with a cargo of “army supplies”. On the 26th, in bad weather 55 miles south of Prince Rupert, while running without radar and relying upon the echoes of her whistle, she sought shelter in Grenville Channel.

Proceeding in a rain so heavy that it almost completely obscured visibility, she struck the rocks of Pitt Island, ripped open a 12-metre-long gash in two of her holds and began listing to starboard. Just 20 minutes later, she was gone.

Fortunately for her 48-man crew and Irish setter mascot, the tug Sally N and the Union Steamships’ S.S. Catala were on hand to rescue them.

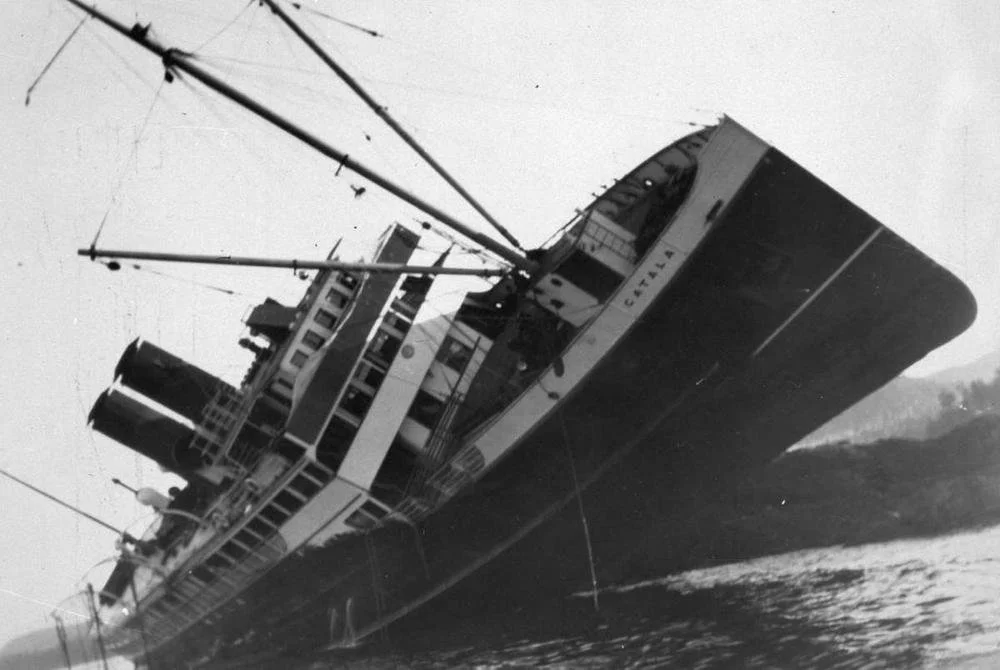

The Union Steamships’ coastal liner Catala helped to rescue the Zalinski’ crew. --Wikipedia

Not so fortunately, her cargo—said to be “at least” 12 500-pound (230 kg) bombs, “large amounts” of .30 and .50 calibre ammunition, an estimated 700 tonnes of bunker oil, truck tires and axles—wasn’t saved and went to the bottom, in her case a ledge, 27 metres down.

End of story—not.

In September 2003, the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Maple reported an oil slick off Lowe Inlet. (How ironic that Lowe Inlet Provincial Park is described as “One of the busier, most attractive and most regular stops on the Inside Passage due to the wondrous site of the waterfalls and migrating salmon viewing.”)

Verney Falls, Lowe Inlet Provincial Park. The horrendous effect of old bunker oil in these waters can be imagined.—Lawrie MacBride, Wikipedia

Three days later, the Canadian Coast Guard’s Tanu took samples but was unable to identify the source. When the CCG revisited the scene after a commercial airline pilot reported a large slick, they found that three miles of shoreline had been fouled.

Suspecting an old wreck in the area, they went to work with a remote control underwater vehicle which located the bones of the Zalinski, resting upside down, and divers were sent down to plug the holes in her hull. For three months, teams of divers were stationed on three large on-scene floating camps with a command post in Prince Rupert.

S.S. Catala was no stranger to shipwreck herself, having become an almost total loss after stranding on Sparrowhawk Reef in 1927. Repaired and returned to service, upon eventual retirement from service she became a floating hotel until she was wrecked off the Washington coast—this time for good. —Wikipedia

According to a private company involved, Western Canada Marine Response Corp., “The operation involved close collaboration between WCMRC, the Canadian Coast Guard and the Gitga’at Nation, on whose territory the spill occurred. WCMRC’s Fisherman Oil Spill Emergency Team, as well as wildlife advisors and shoreline assessment teams, were also involved.”

Holes were drilled into the hull to allow the extraction of tonnes of bunker oil and oil-fouled water. This relieved the immediate threat but, as has been seen, only bought time. Then operations were temporarily halted when research unveiled the old transport’s cargo of munitions.

While a plan of safely dealing with the rest of her oil was devised, mariners were warned to stay clear by at least 200 metres (660 feet). In July, 2013, the federal government undertook a “significant environmental protection operation,” returning to the site in 2015 and 2018, at a total cost of $50 million.

That was 11 years ago and the oil is still leaking from the Zalinski. It’s estimated that 27,000 litres of oil remain in the wreck. In 2022, it was the turn of the Gitga’at and Gitxaala Nations to work with their emergency partners, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the B.C. Ministry of Environment and Climate Change.

It was reported that the rapidly disintegrating Zalinski was in a precarious state, resting bottom-up on a rocky ledge and beset by five-knot currents and tides in an area subject to extreme weather conditions. She’d also begun to collapse within herself. All of these factors made the work of divers highly hazardous while contributing to the spread of the leaking oil.

Over the years, the wreck has been kept under a careful watch by the CCG.

None of these later news reports mentioned other toxic undesirables in the Zalinski’s cargo. Cowichan blogger Larry Pynn (www.sixmountains.ca) did that in Hakai Magazine in 2017. These included: 100 tonnes of possible pollutants that included gasoline, oil and lube, paint, turpentine, and carbon tetrochloride.

Besides the munitions mentioned in other reports he cited 32 boxes of bomb fuses, 20 cases of blasting caps, 26 boxes of hand grenades, 10 boxes of tear gas grenades and 473 boxes of small ammunition.

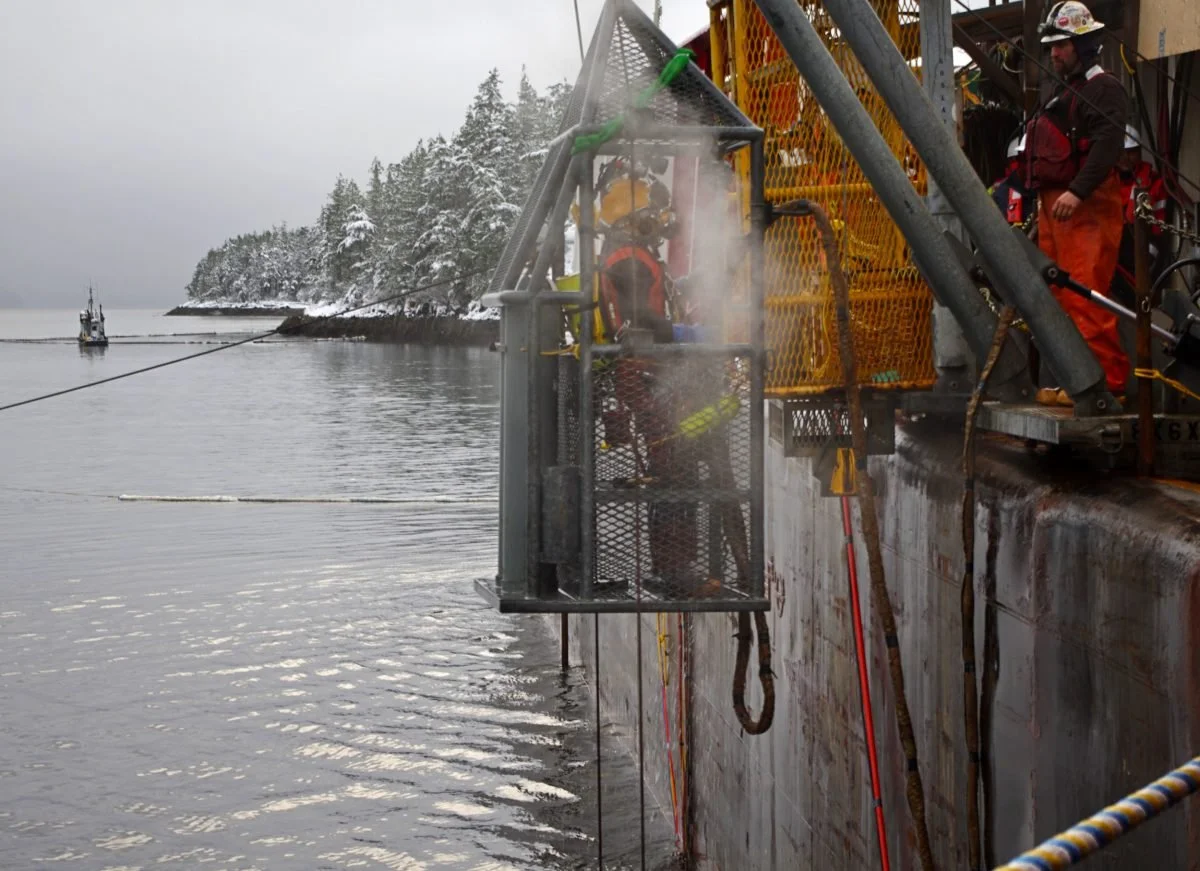

Even if it can be assumed that these were quickly disseminated in Grenville Channel, or have been disarmed, so to speak, by exposure to salt water over the past 78 years, the remaining oil is still a threat to all forms of sea life in the area. Hence, this year, the federal government awarding a $4.9 million contract to an American company to use a proven successful extraction method called “hot tapping.” The month-long operation involves cutting a 10-centimetre hole in the steel plate of the wreck without spilling any of the oil inside.

“That’s a challenging thing to do,” explained a company spokesman.

In another interview he summed up the operation this way: “We’re patching what hasn’t worked in previous operations, as well just trying to seal down the hull as much as possible.”

Divers prepare to descend upon the wreck of the Zalinski in another attempt to stem her leaking oil. —Canadian Coast Guard

Effectively, it’s going to be a matter of letting a sleeping dog lie by allowing what’s left of the ca 1919 Brig-Gen. M.G. Zalinski rust in peace. “We can’t remove such a sensitive, fragile thing in one piece. And if we did decide to do that, we’d still know that there are little pockets of trace oil throughout the hull and it may not be best for the environment.”

History all but repeated itself in March 2006 when the B.C. ferry Queen of the North struck Gil Island, just south of Grenville Channel.

Crew members and all but two of the 59 passengers survived but the Queen slipped under, 90 minutes later, with 225,000 litres of diesel fuel, 15,000 litres of light oil, 3200 litres of hydraulic fluid and 3200 litres of stern tube oil. The fact that she’s down deep, 430 metres below the surface, led officials to believe that most of her lighter fuels were dispersed by wind and tide or evaporated with minimal environmental damage.

Adding to the irony, the Queen had just passed the wreck site of the Zalinski when she impaled herself on Gil Island.

This time, the Gitga’at people aren’t taking any chances and are keeping watch on the grave site for any signs of leaking oil.

* * * * *

There’s another underwater ticking time bomb, the wreck of the 3286-ton S.S. Trader, off Cape Flattery.

This 22-year-old nondescript workhorse made naval history in June 1942 when she became the second merchant vessel to be sunk off the Pacific Coast during the Second World War. Sailing under charter to the U.S. Army from Port Angeles to San Francisco with a cargo of newsprint, she was torpedoed off the entrance to Juan de Fuca Strait, 35 miles southwest of Cape Flattery, on June 7, 1942.

This was six months after the same Japanese submarine sank the first American merchantman of the war on the first day of the war, Dec. 7, 1941.

That victim, the Honolulu-bound Cynthia Olson, went down with all of her 35- man crew; happily for the 57 men aboard the Trader, despite some injuries from the explosion, there was but a single fatality.

Two weeks after sinking the Trader, the I-26 shelled Vancouver Island’s Estevan Point lighthouse.

Unaccountably, despite repeated sightings of Japanese submarines off the west coast, and at least 15 attacks on merchant shipping over the previous six months, Capt. Lyle Havens had contended himself with posting lookouts but not setting a defensive course. Consequently, the I-26, running at periscope depth, had easily closed to within firing range.

According to HistoryLink.org, the torpedo truck the Trader just aft of her number four hatch, shortly after 2:00 on Sunday afternoon of June 7th, blew off the hatch covers, sent 2000-pound rolls of newsprint flying into the air, and toppled her main mast and radio antenna.

Engines stopped, her holds filled with steam and ammonia fumes from her refrigeration plant overcame some of the crew as they began lowering the lifeboats. As her radio operator continued to send SOS signals despite her broken antenna, they managed to launch the port lifeboat and two cork rafts and to evacuate the ship in calm seas. The ill-fated Coast Trader slowly sank, stern-first, 40 minutes after she was hit.

A halibut schooner picked up the survivors in the lifeboat late next day after they rowed all through the night in the belief that their distress signals hadn’t been heard. By the time the fish boat could arrive, however, the weather had turned stormy, with 60 knot winds and the lifeboat had become separated from the rafts. Those in the boat, by this time cold, wet and miserable, the injured suffering from their unattended wounds, were taken to the Coast Guard Station at Neah Bay.

It was dawn of June 9, some 40 hours after they abandoned ship, before a search aircraft spotted the rafts. The Canadian corvette HMCS Edmunston picked up the remaining survivors but too late, sadly, for 56-year-old cook Steven Chance, who'd succumbed to exposure.

The U.S. Government, loath to admit a torpedoing so close to its shores, attributed the sinking of the Coast Trader to “an internal explosion.” And so the record shows to this day.

The Trader’s hulk, largely intact, was found, 140 metres down, in 2016, just inside Canadian waters—not in Washington's Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary as was long believed. Underwater archaeologists joined with James Ballard's Ocean Exploration Trust of the RMS Titanic fame to examine the Trader with a robotic submersible.

She's one of 87 shipwrecks of concern to the U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration for their potentially harmful pollutants as they continue to deteriorate. The Coast Trader was carrying more than 7000 barrels of heavy Bunker C fuel.

As of eight years ago, it appeared that they hadn’t leaked—which is just as well as their contents will, according to computer projection, wash ashore on Vancouver Island’s west coast.

* * * * *

Even more recently, seeping engine oil from the sunken Holland-America freighter M.V. Schiedyk required environmental remediation. Today, there are polluter-pay regulations but, back in 1968, both the ship’s owners and insurance underwriters were able to legally wash their hands of the wreck and any environmental cleanup.

So, again, two years ago, the Coast Guard, on behalf of the Canadian Government, had to step in with the aid of private contractors, all at public expense.

Shortly after the Schiedyk cleared Gold River, Jan. 3, 1968, with a cargo of grain and wood pulp, her rudder failed and she struck a submerged reef off Bligh Island in Zuciarte Channel. Her crew of 34 escaped unharmed but, hours later, she slipped under, coming to rest on the reef and taking 600 tonnes of Heavy Fuel Oil down with her.

The Schiedyk begins her death plunge.—https://www.nationalmuseumsni.org/

Attempts were made to control the oil that began seeping from her tanks and at some point she slid off the reef, landing upside down as had the Zalinski, and the leakage seemed to cease. However, in mid-September 2020 a “mystery” oil sheen was reported to the Ministry of Transport. Historical and physical research identified the almost forgotten Schiedyk as the villain.

An Integrated Response Plan as it’s now called was put together that included several federal ministries, the province and the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation.

Only a bureaucrat could have written this summary of the massive operation: “The multi-phased response included the identification and protection of sensitivities, containment and recover [sic] of oil; a technical assessment of the wreck by Resolve Marine utilizing ROVs [remote controlled underwater vessels] for non-intrusive, and then intrusive surveys; a bulk oil removal operation; and a final recovery and monitoring phase.

“This response is the longest ongoing operation the Canadian Cost Guard has ever been engaged in.”

It remains to be seen if the final bills are in for the recovery of oil from the Brig.-General M.G. Zalinski.