Anyox: The Town That Got Lost

Karma. It’s a curse, I tell you.

Hard as it is for me to believe, it’s been almost 50 years since I wrote Ghost Town Trails of Vancouver Island and it’s still in print after several changes of format and cover, and a slight tweak of the title and byline.

I also wrote two other B.C. ghost town books, on The Lower Mainland and Okanagan-Similkameen. There were to be several more: on the Cariboo, the East and West Kootenays, the Boundary Country and northern B.C. But life took a turn and, with the exception of some magazine articles, newspaper and online columns, and Riches to Ruin, my history of the copper mining boom on Mt. Sicker, I’ve drifted from a subject that has intrigued me since childhood.

But life, it seems, has taken another turn and here I am, looking into my vast archives on B.C. ghost towns again, thanks in part to Blake MacKenzie’s virulently popular Facebook website, Gold Trails & Ghost Towns.

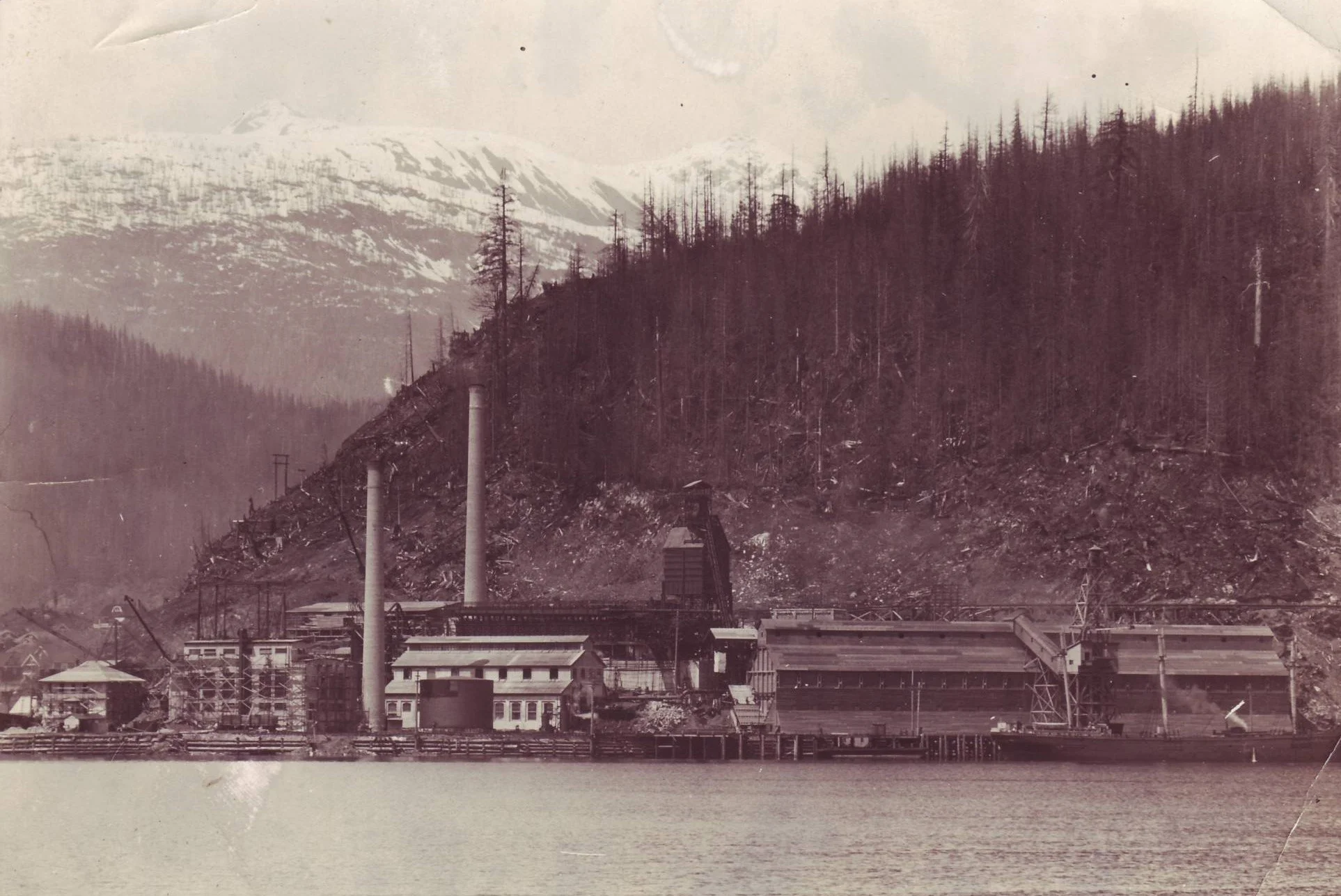

Anyox, B.C. —Courtesy Ozzie Hutchings

All of which reminded me of the late Ozzie Hutchings, the unofficial historian of the northern coastal community of Anyox (An-e-ox.). Back in the 1960s, Ozzie set out to compile and record the history of this copper smelting town on Alice Arm, just below the Alaskan border, which was abandoned by its owners in the 1930s.

The amazing thing is, because the Granby Co. built everything to last of concrete, much of the town is still there in the wilderness, 90 years later. You can even book a tour of the old town site which, for the most part, stands like a ghost from the past.

Ozzie Hutchings is long gone now but he left me his files and photos. Hence this week’s story of Anyox, The Town That Got Lost.

I should explain that I’ve borrowed the title from the only book ever written on Anyox, by the late journalist Pete Loudon who grew up in Anyox. As he was much too young to know its story from a personal viewpoint, having left when he was only 12, he used Ozzie’s research and, unintentionally, I’m sure, stole Ozzie’s thunder.

Ozzie was crushed for a time but he did write a book, with my help, of northern B.C. stories, and his research material was used for a book on the history of neighbouring Stewart, B.C. that was published by that town’s chamber of commerce.

But the story of Anyox, as compiled and told by Ozzie Hutchings, remains in a filing box in my Archives.

Several years ago, grandson Gord Hutchings and his brother spent a week at the former town site and shot 100s of photos that Gord used in a fascinating power point presentation that he gave to local clubs and groups.

It’s hard to comprehend that Anyox achieved a population of almost 3000 residents and came and went in little more than 20 years. What follows is a brutally condensed sketch history of this remarkable smelting town based upon Ozzie Hutchings’ manuscript from his years of research and personal memories of living in Anyox as a lad then working as a machinist for the Granby Co.

* * * * *

But, first, what was and where is Anyox, B.C.? Here’s Wikipedia’s thumbnail:

“Anyox was a small company-owned mining town in British Columbia, Canada. Today it is a ghost town, abandoned and largely destroyed. It is located on the shores of Granby Bay in coastal Observatory Inlet, about 60 kilometres (37 miles) southeast of (but no land link to) Stewart, British Columbia, and about 20 kilometres (12 miles), across wilderness, east of the tip of the Alaska Panhandle.”

Over to Ozzie Hutchings:

For 20 years, Anyox was the largest copper producing and smelting plant in the British Empire. Today [he wrote in 1974], but for the odd concrete ruin at the headwaters of Observatory Inlet, little remains to indicate that here, half a century ago, 2700 persons lived and prospered.

Although this “company town” yielded more than 25,000,000 tons of ore during its 21-year history, by 1935 the huge ore reserves of the Hidden Creek Mine were almost exhausted., The resulting drop in production, coinciding with an all-time low in copper prices [this was mid-Great Depression—Ed.], forced the closure of the mine and smelter, and spelled the end for Anyox.

Within months, its population of 2700 souls had drifted away, never to return...

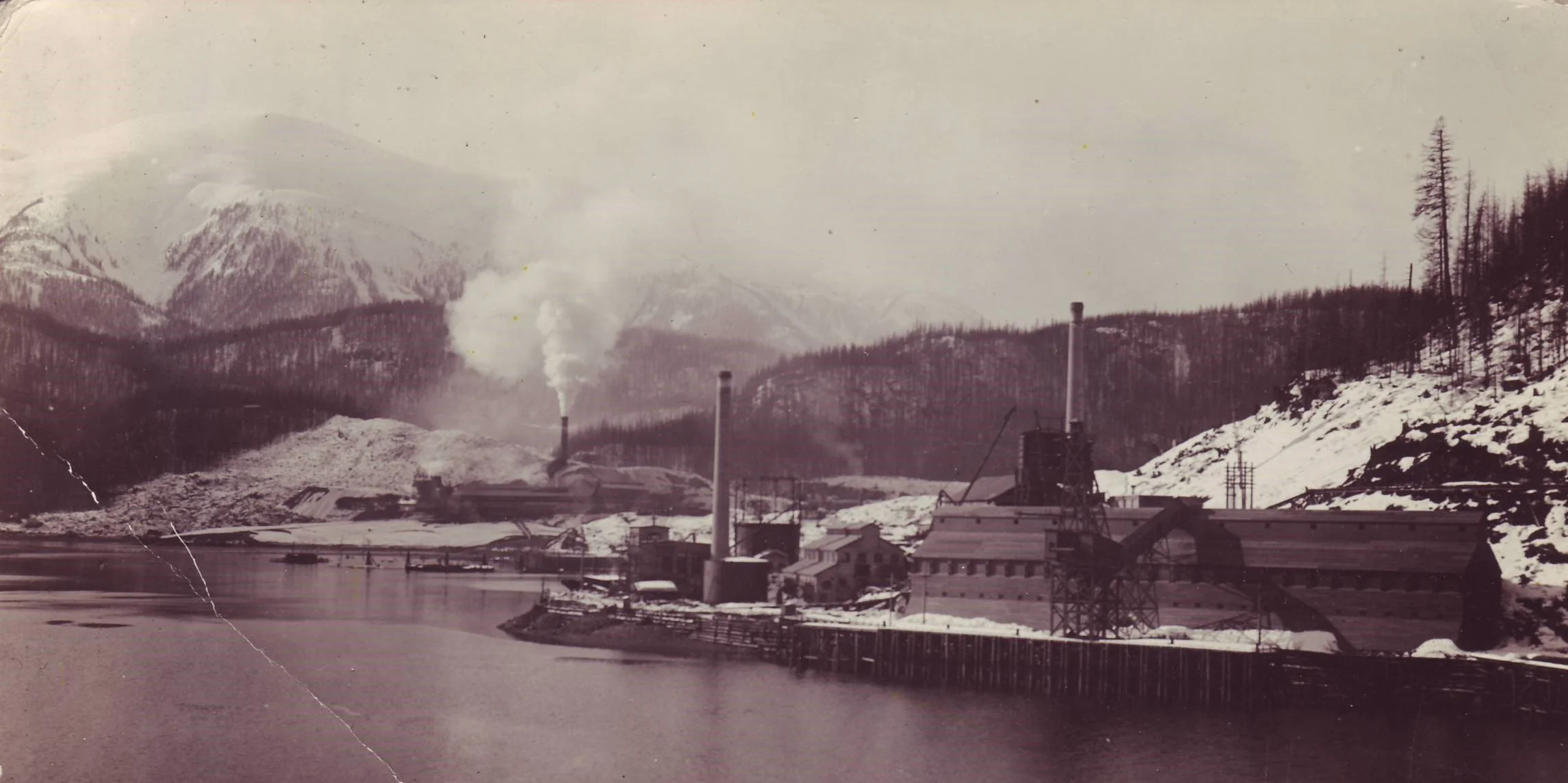

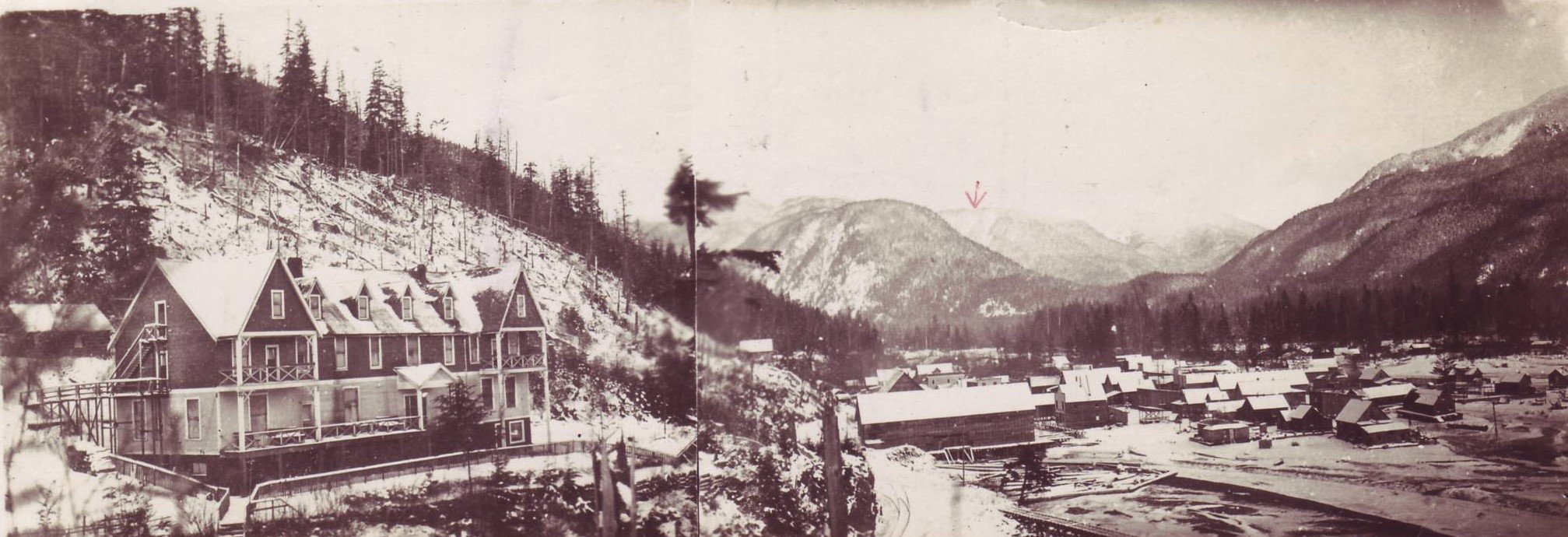

As these photos show, Anyox was no shack-town! —Ozzie Hutchings

Tucked away in the mountainous country of northeastern British Columbia, Hidden Creek flows through a small valley into Goose (Ecswan) Bay, which is about 40 miles north of Kincolith (Place of Scalps), the Indian settlement at the mouth of the Nass River, some 16 miles west of the headwaters of Alice Arm, and 18 miles south of the headwaters of Hastings Arm.

The nearest city is Prince Rupert, 120 miles to the south.

Although the first commercial interest in this isolated region dates back to 1831 when the Hudson’s Bay Co. established a trading post at Stan Meliksh on the Nass (shallow water and terrific winter winds forcing the post to be moved in 1834, to what is now Port Simpson, 40 miles to the south), the first recorded evidence of miners being in this region was the date, “Aug. 1874,” carved into a tree near what became the famous Dolly Varden Mine, 20 miles northeast of Alice Arm.

This tree would have been blazed during the Cassiar gold rush.

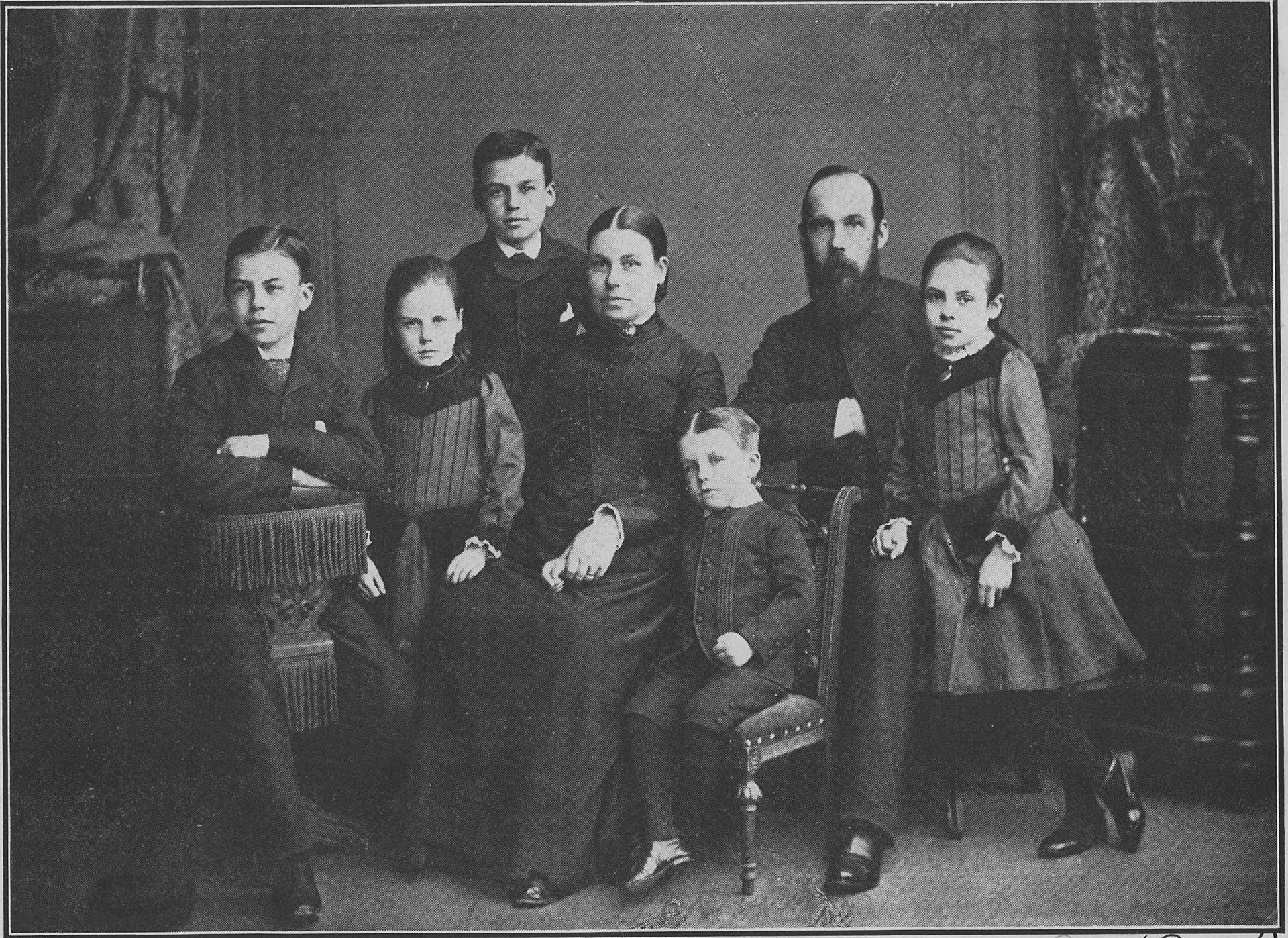

There was further mining interest in this area in following years but it was not until 1898 that development which would ultimately result in the establishment of Anyox, was initiated. Somewhat surprisingly, it was none other than the illustrious Archdeacon W.H. Collison who first learned of a “mountain of gold” at the head of Hastings Arm, through three Indian chiefs.

W.H. Collison and family circa 1890. —Wikipedia|

—Unknown author or not provided - U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Public Domain

Upon investigating, the missionary met Albert Flewin and Dan Robinson who agreed to accompany him. As a result, the Eureka group of mineral claims was located on Hastings Arm, Upon their return trip, while hunting, Collison noted the reddish colour of the rock lining a creek bed, and he and his partners staked the co-called ‘Bonanza’ group also.

With the staking of these pioneer clams, mining interest in the region increased steadily, initiating development of the Bonanza group yielding promising results. Collison, in June of 1899, staked two new clams at Mammoth Bluff, on Hidden Creek, which he called the Alpha and the Beta.

The following year, a large American mining corporation obtained options on the Bonanza and Mammoth Bluff claims for $50,000 and $6,000 respectively. However, by 1902, work on the Bonanza group was abandoned. Despite continued faith in the claims on Hidden Creek, work was later discontinued there also.

And so it went, as others tried their luck in this region, Rev. J.B. McCullah of Aiyansh Indian village, staking one claim on the abandoned Hidden Creek property which he named the Alpha.

This and adjacent claims were later consolidated by a man named Rudge. Two years after, J.E. Hills obtained an option on this property for $55,000, investing heavily, with good results, until the “panic” of 1907 halted further development when Hills sold his option to M.K. Rodgers for $135,000.

Once again, new management invested heavily, with the result that, in 1911, the giant [Granby Consolidated Mining, Smelting & Power Co,] purchased controlling interest in the Hidden Creek Mine for $500,000.

And with the Granby Co.’s arrival, some eight owners later, a new town—Anyox—was born.

The Anyox Hotel on the left. —Ozzie Hutchings

Originally known as Goose Bay, then changed to Granby Bay with the construction of a modern city in the forest, the name Anyox was chosen. The English form of the Indian name for the town’s location, it’s generally translated as Hidden Creek, after a winding creek which passed through a low piece of land originally concealed by a thick growth of timber.

Due to its natural seclusion, “Hidden Creek afforded a refuge more than once for the Indians of Goose Bay who hid, with their families and possessions when the fierce Haidas raided the tribes on Observatory Inlet.

Anyox, therefore, seems more correctly translated as “a place of refuge.”

Whatever the origin of its name, Anyox now spelled progress and prosperity as the Granby Co., proceeded to carve a modern, thriving industrial empire from the surrounding hills and forests. Prior to its arrival, considerable work had been done at the Hidden Creek Mine and a small dock had been constructed at the beach.

Adjoining this dock were the first buildings of what was to become the thriving community of Ayox. These first, crude structures comprised the “beach rooms” (a boarding house) and the mess hall, able to accommodate 50 men, the employment office and a log cabin later used by the provincial police constable (for many years my father, John Hutchings).

This original dock soon became too small to handle the increase in shipping and the company anchored a large buoy in the bay to which barges could make fast, their freight being ferried ashore in scows.

The road to the mine, about a mile and a half to the north, followed the “side-hill,” as we always called it (actually it was the base of the hillside) from the dock and was built entirely of wood (mainly 2-by-12 planking laid side by side, crosswise). This was widened and improved when the Granby Co. was ready to build at the mine site. Large bunkhouses, a mess hall and a number of residences with all modern conveniences were built; also a library, the superintendent’s office and storage buildings.

Two stories high, the bunkhouses had shower baths, drying rooms and lockers for the workers’ clothes in the basement, the ground floors being divided into separate rooms, and the upper floors consisting of one common room furnished with cots. These were called the “bullpens.”

Initial construction at the beach consisted of the laying out of the first section of the town site. The main road and new homes were soon started, as well as wooden bunkhouses and a mess hall. Development here increased dramatically in 1911 when the Granby Co., which originally had planned to ship all ore to the smelter at Tacoma, decided after investigation that they had all the requirements for their own smelter at tidewater on Granby (Goose) Bay.

With the decision to build a smelter, work on the town site and mine was stepped up, construction of the dock facilities, town site and power plant at the beach proceeding at all possible speed.

The company also had to build a railroad to the mine and smelter sites to handle the heavy machinery and supplies for this tremendous undertaking, the first steps being the logging-off of large sections of the proposed town site.

Once the surveyors had done their work, three trunk line sewers were laid, then streets of 2-by-12 planking, so laid out as to follow the contour of the land. In the meantime, more bunkhouses and an enlarged mess hall had been completed, down on what was known as the Flats, work proceeding rapidly on the railway right-of-way and on No. 1 powerhouse and dam.

“Early stages of the Big Fire 1923, at the Beach town site.” —Ozzie Hutchings

One of the many benefits of building here was the fact that Granby Bay is very deep; so deep that an ocean-going vessel could dock even at low tide. Consequently, the dock was built parallel to the shore for a length of 800 feet. Fifty feet wide, it had two sets of railway tracks and three sets of travelling ore bunkers which moved with the electric cranes.

The actual town was built with the same care and attention to detail as went into the construction of the smelter and mine. A 60-pound pressure waterworks system was installed and connected to each of the 85 houses (all of which had three to seven rooms, indoor plumbing, electric lights, water and sewer connections).

Also constructed were a large recreation hall, complete with billiards and pool tables.

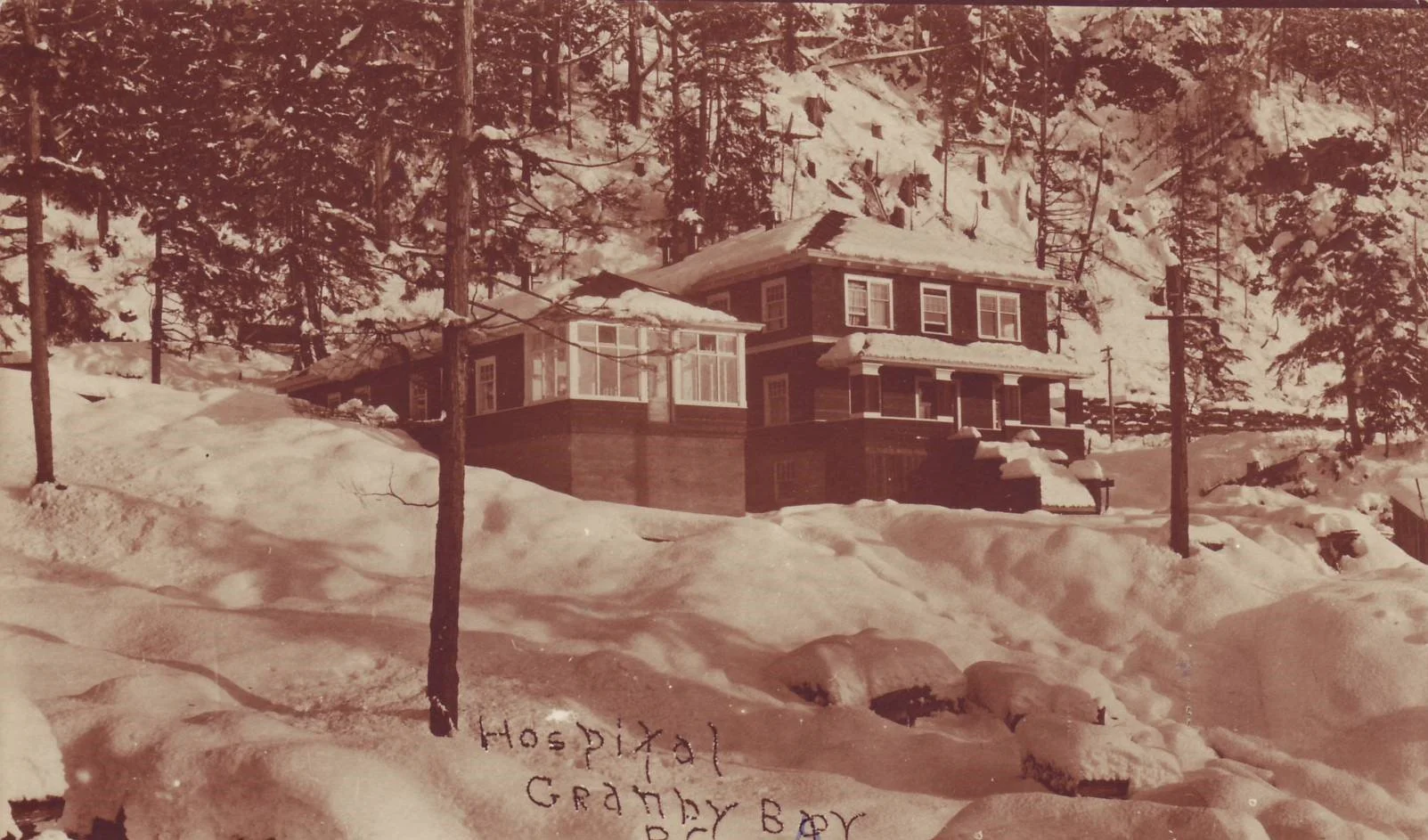

The floor above was the theatre which doubled as a dance hall, and a hospital equipped with the latest in X-ray equipment, A fully modern 45-room hotel boasted steam heat, hot and cold water, and telephone service in every room. A steam plant in the basement of a two-storey office building heated the telephone exchange and offices upstairs, as well as hospital, hotel, recreation hall and general store.

A three-storey, fireproof concrete department store with refrigeration plant was erected at the west end of the dock. On the main road from the dock to the smelter, a variety of buildings was erected, including a sawmill, brickyard, a paint shop and the foundry (castings of all shapes and sizes, up to eight tons) being made here under the careful eye of foreman Bill O’Neill.

Other structures included the main carpentry shop and tin shop, a number of bunkhouses and some rooming houses.

When a long, one-storey rooming house, built near the bridge which crossed Hidden Creek, connecting the town with the Flats burned down, the company replaced it with two new rooming houses of concrete. Most of the new rooms were for double occupancy, containing two single beds, a dressing table with a mirror, two chairs, hot and cold water, and private entrance.

There was overhead lighting, blinds and curtains at each window, and steam heat. These rooms were brushed out and tidied, the beds made, daily. Linen was changed twice a week, the floors washed weekly.

Looking more like an expensive private home, the Anyox hospital. —Ozzie Hutchings

The housekeeping chores were performed by Chinese employees, all of whom did their work conscientiously and were well liked. For all of these amenities, tenants paid $40 per month for double rooms, $45 a month for singles.

Nearby was the mess hall which could seat 250 men at a time, complete with all of the latest innovations in kitchen facilities, cold storage, bakery and laundry. For a dollar a day, workers enjoyed good food and service from a multi-national staff which consisted of an American chef, Chinese cooks and kitchen staff, and numerous waitresses of many different nationalities.

After a hard day’s work in the smelter, or out in the cold weather, the men appreciated a little service with their meals and many of these girls married the men upon whom they waited...

In short, in an era when the term “company town” was bandied about in rather unpleasant terms, life in Anyox, but for the isolation, was not only equal, in my opinion, to life in the “outside” towns of that day, but superior.

Company housing was good, with water, light, toilet and bath in every home, complete with telephone if you wished. We had excellent medical and hospital care at reasonable rates, good schools and all the entertainment we could have wished.

In fact, the only thing “missing” from Anyox was a slum!

The Granby Co. Dam is still there! —Ozzie Hutchings

All of the amenities, such as housing and public facilities operated by the Granby Co. were done so at cost; the rents were reasonable, the prices at the company store competitive. Anyox was a fine place to work and a fine place to live. When the Depression and failing mine production forced the company to close down Anyox in 1935, there were few of its residents who were not sorry at the prospect of leaving the town in which they had raised their families, many of them having lived there since the beginning, in 1914.

One of the ironies associated with this “company” town is the fact that Anyox was built to last. Consequently, when changing fortune decreed otherwise, the little city on Observatory Inlet was reluctant to die. What the salvage firms could not recover was left in the wilderness, forest fires destroyed those wooden structures remaining, and the plank roadways.

But even today, some 35 years after [as of 1974], many of her concrete ruins stand as silent monuments to a wonderful town. One which many former residents now scattered about the globe will long remember with affection: Anyox.

* * * * *

Thus, in 2000 words, Ozzie Hutchings condensed the story of Anyox’s 23 years. His unpublished book manuscript is over an inch thick.

If his account seems to border on the idyllic, perhaps, by the 1970s, he was viewing his memories of his own life and that of his family in Anyox through the rosy hue of time. I don’t know why he made not even passing mention of a bitter strike by Anyox mine workers who, in 1933, complained that their living accommodation was consuming half their wages. They demanded a 20 percent cut in boarding and rents, and a pay raise of 50 cents per day. This was, remember, in the middle of the worst economic depression in history.

The Granby Co., as had so many mining companies before and since, responded with a call for police protection and imported private security personnel. When the strike was called off, more than 300 disgruntled employees left. It was all academic by then; with the ore all but run out and depressed copper prices, the company announced closure.

They’d already shuttered their Vancouver Island coal mine (1917-1932) at Cassidy, V.I. where, it should be noted, there had always been a waiting list of those hoping to work in what has been described as the perfect company town. Just as they had in Anyox, the Granby Co. had built a model community for workers and families.

It, too, was stripped of its salvageable assets and all but vanished.

* * * * *

In 2011, grandson Gord Hutchings and his brother set out to see for themselves what was left of the wilderness community that Ozzie had recorded with his writings and his fold-out Kodak camera. Arriving by kayak via the more modern ghost town of Kitsault, they spent five days exploring the extensive town site and gorging on the huckleberries which grow in profusion in the acid soil and which attract grizzly bears from afar.

The lush vegetation that prevails today, it should be noted, is the result of Mother Nature having had to totally regenerate this stretch of the Portland Canal as, when the smelter worked 24/7, the toxic fumes killed all vegetation for miles around.

One of Gord’s key goals was the 175-foot-tall smelter smokestack, still standing, which Grandfather Ozzie had climbed when it was new, to take what would have been a breathtaking photo from the top. But, having got there after an exhausting climb up the steel rungs inside the stack, Ozzie realized that trying to work with his cumbersome Kodak while trying to hold on would have been perilous in the extreme.

So, no picture.

As it turned out, no breathtaking photo from the top of the smokestack for Gord, either. The stack with its steel ladder is still there but he isn’t comfortable with heights, so...

But he did fill another goal, also at some risk. After jury-rigging a ladder in the powerhouse he was able to retrieve a light bulb. But not just any light bulb.

This one, which he knew from reading Ozzie’s unpublished manuscript, was embossed STOLEN to discourage employees from taking them home for personal use. Better yet, it still works! It’s but one of a kayak-load of artifacts—old bottles, insulators, pieces of electrical apparatus—that he was able to haul home.

His third wish was to find the town’s cemetery. It took some doing but was worth the effort. All but overgrown, the moss-covered graves of ex-servicemen have an unusual marker: army helmets cast of concrete.

It was Granby Co. policy to employ returned soldiers whatever their physical limitations resulting from their military service. Those who died prematurely now sleep peacefully in the trees and rarely disturbed by visitors.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.