B.C.’s First Gold Rush

“Great excitement has been recently produced in Victoria by the exhibition of a nugget of pure gold weighing 14 ounces, procured by the agents of the Hudson’s Bay Company from the Indians of Queen Charlotte’s Island. There is a generally prevalent impression founded on the discovery of gold in that island in the year 1851, that it will yet become a productive gold field.”

It was a gold nugget such as this that sparked an unwelcome rush to the Queen Charlotte Islands in 1850. —www.coinnews.net

Note the reference to 1851.

That’s a full six years before the first reports of the discovery of placer gold by First Nations prospectors began to seep out of the B.C. Interior and, in turn, start one of history’s greatest gold rushes to ‘Fraser’s River’ the following year.

That stampede, followed by an even greater treasure hunt in the Cariboo, placed virtually unknown mainland British Columbia on the world map, and set it on course to becoming Canada’s westernmost province.

But who remembers the Queen Charlotte (Haida Gwaii) gold rush of 1850, with its reports of fabulously rich gold deposits that were jealously guarded by its fierce residents?

Mainland tribes had no hope whatever of stemming the white tide. But the Haidas guarded their seaside ‘mines’ to the point of committing piracy...

* * * * *

El Dorado! This, it was claimed, was the vast, unknown hinterland of British Columbia in the 1850s.

Overnight, with the discovery of yellow pebbles in Mainland streams, the wilderness became alive with fortune seekers from around the world and B.C.’s future as a crown colony and Canadian province was assured.

All but forgotten or overlooked is the fact that the resulting stampede of humanity to the banks of the Fraser River came a full six years after our first gold rush. The history-making claim to being first belongs to what were then known as the Queen Charlotte Islands.

“Two pieces of gold, nearly pure, weighing 4 1/2 and 1 1/2 ounces, and a piece of auriferous quartz”—wrote James Douglas to his superiors in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s London office, in mid-August 1850, had been discovered by the Indigenous inhabitants of the west side of “Queen Charlotte’s island, near Englefield Bay and Cape Henry”.

Hudson’s Bay Co. Chief Factor James Douglas informed his superiors in London of the gold strike. —Wikipedia

Samples delivered to Fort Simpson understandably aroused the fur company’s interest although it wasn’t until May of the following year that Chief Factor John Work visited the area, to make four exploratory blasts and gather samples. A subsequent expedition led by Pierre Legarre was less successful, his men failing to find the “mine” but discovering that ‘Queen Charlotte Island’ was, in fact, a group.

Work then returned to the site with HBC Capt. W.H. McNeill aboard the company vessel Una with men and equipment.

HBCo. Chief Factor John Work found gold—only to lose it. —Wikipedia

Despite their efforts of almost a week, this party found little. The diggings, situated on the beach, Work noted, seemed to extend below the water’s edge as indicated by the fact that the best samples, in the form of “loose stones,” were found below the tideline. Local Natives had been the most successful, having found one rock containing nearly two pounds of “pure” gold and a second one weighing six ounces. These, they offered to sell to the traders at what Work deemed to be an exorbitant price so he and his party returned to Fort Simpson.

By this time, word of the strike was getting around—despite efforts by the fur company to keep knowledge of the Moresby Island ‘mine’ to itself.

Shortly after Work’s second visit, the sloop Geo. Anna, Capt. Rowland commanding, arrived in Olympia, Washington Territory, with “very interesting news from the goldmines on Queen Charlotte’s islands”. Not only did Capt. Rowland have a story for the Oregon Spectator, but samples as well.

“Some beautiful specimens of virgin gold bearing quartz, the latter of the richest quality [that the correspondent, A.M. Poe] ever saw.”

After testifying to Capt. Rowland’s credibility—he was a “gentleman of veracity and experience”—Poe described the “mines” as being “equal, if not superior to anything of the kind yet discovered. The gold is found on the surface of the ground near the beach, and is dug by the natives in great quantities, without anything like a pick or shovel—having nothing but such tools as they can make themselves, they manage to get from two to eight ounces per day.”

“They are very friendly to the whites and are anxious to have them come and trade and dig with them.”

So it may have been at the start—but the inhabitants’ attitudes towards white prospectors would change, dramatically, and soon.

Late in October, the Una returned to the scene, Capt. McNeill directing his men in the work of blasting away the overburden. Upon their exposing and tracing the vein, they found that it seemed to lead up the hillside. More than ever, the mine looked promising but, this time, the locals—the same ones who’d been reported as friendly and eager to have the whites trade and dig with them—weren’t as gracious.

Now resentful of the HBC’s competition, they became decidedly unfriendly, stealing the traders’ tools and ore samples. When the whites protested, their hosts drew knives and McNeill decided it wise, after only three days, to abandon the venture for the time being.

The Una then sailed for Fort Victoria—and disaster.

Driven ashore on Neah Island during a gale, the vessel was looted and burned by resident First Nations, Capt. McNeill and company having to be rescued by the American vessel Susanna.

But if the HBC was having its difficulties with mining, there were those who were willing to risk any hazard. Capt. Rowland’s arrival in Olympia had coincided with the general realization that the gold boom in California had peaked.

Gone were the golden days of ‘49, and more and more disheartened prospectors were returning to their homes. Although disappointed, they were alert to any rumours concerning new strikes, and reports of gold in the Queen Charlotte Islands aroused the entire West Coast. Before long, the schooner Exact, loaded with Oregonian adventurers, cleared Portland for the treasure of Moresby Island which, the Spectator assured its readers, promised to be a sure thing.

Few paid heed to the fact that, among those aboard the Una when she stranded, were the men of the American vessel Georgianna—Capt. Rowland commanding—which had outfitted at Olympia and sailed for the new gold fields. Outbound, the vessel spoke with the Demaris Cove, commanded by another ‘49 veteran, Capt. Lafayette Balch.

Informed as to the nature of their expedition, Balch enthusiastically agreed to join them as soon as he rendezvoused with the brig George Emery. In due course the goateed mariner-miner learned that the Georgianna’s company, rather than finding their fortunes, had been wrecked and taken captive.

Balch immediately notified Colonel Simpson Moses, collector of customs in Olympia, and urged the formation of a relief party.

In turn, Moses alerted the army commandant at Steilacoom and sought the assistance of Factor Work, HBC officials having assured him that, due to the time of year, the Haidas likely wouldn’t agree to transporting the castaways to Fort Simpson. Dissatisfied with this response, Moses commissioned Capt. Balch to sail for the north with authorization to pay whatever ransom was demanded and to take with him a seven-man detachment of soldiers.

Seven weeks later, the Demaris Cove returned with the prospectors and their intriguing story of shipwreck and ordeal.

The wreck of the Georgianna, according to one of its company, had resulted from Capt. Rowland’s refusal to heed the advice of a Haida chief named John who’d been employed (upon the high recommendation of an HBC official) as pilot. Choosing his own anchorage, the captain apparently had such faith in his anchors and cables that he’d ignored a worsening gale and his exposed condition.

In the early hours of the following morning, the Georgianna began to drag her anchors then broke loose.

When her frightened crew attempted to make sail, “everything blew away as fast as it was set,” and the beleaguered vessel struck the rocks. At first she shipped no water although the waves made a clean sweep over her decks while her crew huddled below, “to save ourselves from exposure” amid the “greatest order and coolness”.

With daybreak, a volunteer made his way to shore with a lifeline while those aboard chopped away the mainmast. Suddenly relieved of its weight, the Georgianna “bilged and fell immediately”. Rowland and several others drifted ashore on the mast and, when it became apparent that the vessel, by this time floating freely, couldn’t be saved, the remainder of her company escaped to the beach where they were met by a growing assembly of Haidas.

The welcoming committee, some 150-strong, “taking advantage of our exhausted condition after coming through the surf, plundered us of our caps, weapons, and such clothing as they could pull off us”. Those who resisted were threatened with knives and tomahawks. Fortunately for the castaways, their pilot remained loyal and offered them the sanctuary of his home. After being shuttled by canoes, the men were “well received at John’s house”.

Once there, however, John showed his true colours by demanding that they build him a house. In exchange for a structure 36 feet square, and “built in the same manner as an HBC house,” he’d take them to Fort Simpson.

This, his unwilling guests refused to do, “considering it as the first step towards slavery. After a long conversation, John agreed to furnish us with a scanty supply of bad provisions until a favourable opportunity occurred to send an express to Fort Simpson.

“From the 20th of November to the 4th of December we had a succession of heavy east gales, with passing showers of rain. Passed the time in a most miserable manner, and received great annoyance from the Indians over whom the chief seemed to have but little power.”

Twice, notes were dispatched to Fort Simpson as the shipwrecked fortune hunters waited impatiently for rescue. On the second occasion they’d succeeded in persuading John to canoe five of their party to the HBC post where Capt. McNeill was in charge. Despite the fact that McNeill provided these men with provisions and clothing, the Americans received the distinct impression that he was in no way eager to send for their “suffering companions”.

“He promised,” the Georgianna’s log continued, “to send, but made no seeming attempt to do so. The Indians in that neighbour of the fort were threatening to make war on the Haidas, and he seemed to be more anxious for his own safety than to relieve those who were in more imminent danger, although they were people of his own kind”.

Rightly or wrongly, McNeill took all of four weeks to see to their relief. The five men who stayed at the fort, in lieu of payment for the goods and provisions provided them, were made to stand guard daily for the duration.

Throughout this period the Americans suffered cold, hunger and the unbecoming conduct of their hosts. Almost naked, much of their clothing having been stolen upon their reaching shore, they shared accommodation with 10 Haida families, some 60 persons, and a host of dogs in a cedar-planked longhouse. Not all of the prisoners were mistreated (at least not in the accepted sense of the word), one of their number making himself quite popular with their hosts by entertaining them. He soon regretted his acceptance when an old woman who’d adopted him as her son, insisted upon chewing his food for him.

Finally the Demaris Cove, Capt. Balch and company, arrived from Olympia to ransom the captives for five blankets each. The only hitch in negotiations came when most of the Haidas (particularly the “mother”) demanded that the talented entertainer remain with them. At length, this was resolved and the Georgianna’s ill-fated company was released.

No sooner had details of their experiences been reported to American newspapers than the Oregonian renewed the excitement by stating that a crewman of the lost Una had displayed some of the gold he’d recovered with nothing more than a cold chisel. In half an hour he’d obtained an ounce of the “richest quality we have ever seen.”

The rush to the Queen Charlottes—whatever the mood of the Haida Nation—was on!

In a period of two months, six American vessels cleared Californian and Oregonian ports for Moresby Island, as many more planned to join them. Among the first to return was the Eagle, whose crew expressed disappointment. They hadn’t found any gold themselves, that which they brought back having been purchased from the Haidas “at quite double the value”. They did, however, offer hope to others by remarking that gold, as evidenced by the quantities in possession of the Haidas, must exist in quantity on the island.

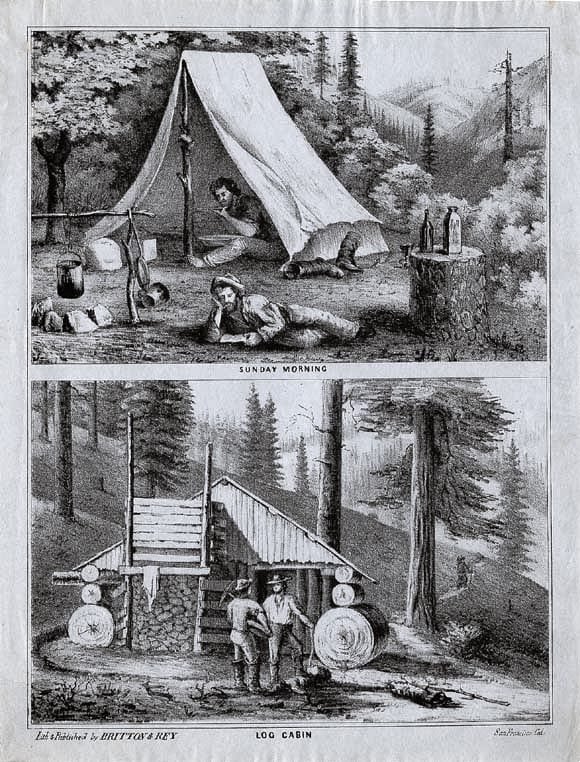

With the gold rush in California slowing down, 100s of frustrated latecomers jumped at the chance of finding their fortunes in the Queen Charlotte Islands—even if they weren’t wanted by the Haidas. — https://library.ca.gov/

Throughout this excitement, the Hudson’s Bay Co., legal claimants by their royal charter to any mineral rights, watched the situation with mounting concern. Douglas regarded the American fortune hunters as invaders and, so as to circumvent further incursions by miners, he ordered Chief Trader J.F. Kennedy and 40 men to sail for the mine site aboard the company vessel Recovery. But for all of their efforts they found gold only in a pocket near the beach, this vein quickly petering out.

While there they were joined by HMS Thetis, Admiral Moresby having arrived to preserve order.

It was then that the schooner Exact arrived in Victoria, its company having spent “a hard winter” exploring the Charlottes. Alas, their attempts at mining had been brief. After a single blast, they found they’d have to fight for everything they got. With insufficient tools for mining, and inadequate strength to guard against the Haidas, they spent much of their time surveying the islands’ harbours, mountains, lakes and rivers. Although they were convinced that “there is plenty of gold there,” the only precious ore that they’d seen for themselves had been in the possession of some Haidas—who’d taken it from the Una’s crew.

As time passed, and more seagoing prospectors visited the islands, the Haidas became bolder.

On Sept. 26, 1852, Capt. McNeill reported that the schooner Susan Sturges, British-owned but sailing under American colours, had been “plundered and burnt” by the Haida. None of the seven-man crew, he wrote, “were lost on the occation [sic[], and she had $1500 on board in gold and silver and a complete trading outfit all of which fell into the hands of the natives”.

McNeill had had to ransom Capt. Roomey, then clothe them upon their rescue as all had been robbed of their clothing This time, there was no accusation that McNeill had tarried in coming to the relief of the hostages, a Portland newspaper acknowledging the “commendable promptness” with which the S.S. Beaver had been dispatched to their relief.

Unfortunately, upon Factor Work’s arrival at the Haida village, the tribe refused to surrender one of their prisoners. When they resisted all pleading, bribery and threats, “it was thought that he has been butchered by them ere this time”.

Interest in the so-called gold mines of the Queen Charlottes had faded even before the undeniably great strikes of the Fraser River. Although James Douglas had been appointed lieutenant-governor of the islands in 1852, as a claim to British sovereignty, most Americans had abandoned the rush for fear of the Haida and in disgust of the poor returns.

Subsequent surveys confirmed what some veteran miners had suspected from the beginning, that the ‘mines’ of Gold Harbour were nothing more scattered small veins. Once the best of these had been exhausted, they said, there was no more.

The gold rush of the Queen Charlotte Islands—with its shipwrecks and Haida pirates—was history, although mapmakers have immortalized those exciting times with Una Point, Mitchell Inlet and Gold Harbour.

* * * * *

Which isn’t to say that there are no significant or promising gold deposits in Haida Gwaii. Just south of Massett are the Blue Jacket Creek beach sands where, in the 1920s, a company held hydraulic placer leases. As late as the mid-’50s it and its successors succeeded only in recovering modest amounts of gold and platinum.

There have been other attempts at full-scale gold mining, at Fife Point and Martell Creek on the coast of Graham Island, in the Oeanda beach sands. These are beach placer deposits, only dust and grains, but small nuggets amounting to 72 ounces were found on Shuttle Island in 1918.

According to the website, Gold Creeks of Haida Gwaii, “The gold content of the beach gravels was derived from erosion of small gold-bearing veins which outcrop along...the shore. The gold veins occur in the Karmutsen Formation.”

Total production of these sporadically operated placer claims appears to have amounted to just under 800 ounces.

As late as July 2021, it was reported that one of three active mining operations in Haida Gwaii, Taseko Mines’ Harmony property on Graham Island, which it had owned for 20 years, had been sold. The sale included 58 mineral clams covering 177 square kilometres. The estimated gold content of the property is three million ounces of gold. A Department of Mines report describes it as an epithermal gold property with a substantial undeveloped resource”.

* * * * *

As another reminder of the historic ‘Queen Charlotte islands’ gold rush, the Royal Canadian Mint struck a “proudly Canadian” $100,000 coin of 99.999 per cent pure gold bearing the design of the late Bill Reid, renowned Haida sculptor, carver, artist and master goldsmith.

The 180mm ‘Spirit of Haida Gwaii’ is said to be the world’s first 10-kg gold con of such purity and the “highest denomination non-circulation” coin in the world. (Another coin, produced in 2007, had a face value of $1 million.)

It’s just as well that no one carries change any more—this puppy would soon wear a hole in you pocket! —www.mint.ca

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.