British Columbia Treasure Chest

Lost treasure is where you find it—quite possibly under your very nose!

I offer this as encouragement to armchair enthusiasts who confine their treasure hunting to television, movies and daydreams. Ironically, few realize that, while there definitely is gold in some of 'them thar hills,' it can also exist, in various forms, much closer to home.

In fact, it might well be under your very nose, unsuspected, at this precise moment.

Don’t believe me?

Check out these recent newspaper headlines:

• Unopened Nintendo game from 1987 sells for $870,000

• GP finds painting in Courtenay thrift store that could be worth a small fortune

• Rare Coin in a Candy Tin Sells At Auction For $350,000

Or, better yet, the so-called Saddle Ridge Hoard. I quote:

“One day in April 2014, a California couple was on a walk with their dog when they found a metal can sticking out of the ground, according to Dan Whitcomb of Reuters. Rusted from age, they were able to open the can after digging it out finding a large cache of gold coins inside...”

Okay, that one’s a real exception. But don’t kid yourself; treasure, like beauty, can be in the eye of the beholder and some valuables can look to be anything but.

Here are some case histories much closer to home!

* * * * *

Saanich youth Joseph Johnson was hired to excavate the basement floor of a home at 426 Dupplin Road, Victoria, for an oil tank. Young Joseph dug in—and struck pay dirt in the form of a piece of stainless steel containing five $100 bills, three $50 bills, 20 $20 bills and 10 $10 bills, for a grand total of $1,150. Dated between 1935 and 1937, the currency was in a good state of preservation and quite negotiable.

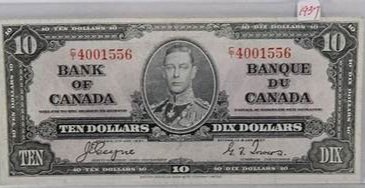

King George VI Canadian 10-dollar bill of the 1930s. --numismaclub.com

When Mrs. Mary Hilda Hawkins died at the age of 72, in September, 1964, official county administrator Ian Horne had found himself in custody of shopping bags containing stocks worth no less than $11,000. Mrs. Hawkins had lived in Victoria’s Beverley Hotel and in the York Hotel on Johnson Street for a week before departing for Vancouver, en route to Winnipeg. Taken ill before boarding the train, she died in hospital. At last report, her valuable treasure was being held for safekeeping by the provincial treasurer until any heirs were located.

A year later, a gardener working at the H.D. Twigg residence on Victoria's upper-crust Rockland Avenue, found a pair of Alexandrite earrings, a sunburst pin, and several other jewellery pieces in some bushes. Valued at almost $300, the treasure trove turned out to have been stolen 13 months earlier from a home on Terrace, one block distant.

A diamond-studded wrist watch and a ring containing a dozen diamonds, taken in the same theft, were not found in the Twiggs’ shrubbery.

Mrs. Flora McLeod, of Sardis, B.C., looked no farther than her own safety box during a visit to her bank, to find treasure. Upon opening the box, she discovered several three-year-old Canadian Superior Oils Ltd. stocks worth $19,000. Amazingly, Mrs. McLeod said she had no idea as to how the stocks came to be in her box.

“They were just one of those things you find in your box,” she shrugged in happy resignation. “I may have inherited them. I don’t know.”

Two months later, Walter Doerksen, 24, and Neil Woelk, 23, both of Cranbrook, made a delightful discovery when moving an old iron bed at the home of Doerksen’s parents. During transfer, they accidentally broke a caster off a leg and $700 in 1937 $10 and $20 bills, rolled up in an empty shaving stick container, had fallen out. Eagerly examining the leg closer, they uncovered a second $700. Doerksen’s parents had bought the bed at an auction 20 years before for $10, Walter sleeping in it for 15 years, before he married and left home.

He split the windfall, 50-50, with friend Woelk.

Lost treasure in the form of a pot of gold came to light in November 1969 when two Victoria brothers found 15 $20 gold pieces. Craig Hodson, 22, and his brother Kim, 15, made the tantalizing discovery when hiking. The honest adventurers handed over their treasure to Saanich police, who in turn forwarded the coins to Ottawa for expert examination.

Alas, although of real gold, the coins were counterfeit and as such automatically became federal property. Had they been authentic, their current value to collectors would have made them worth up to $6,000!

Sadly, they apparently were to go to the Finance Ministry to be melted down, the gold to be added to the federal coffers. At last report, the Hodsons had received no more than the thanks of Saanich police. “They deserve a lot of credit. They found a treasure and yet they turned it in. We want to express our appreciation for that,” said Inspector John Post.

Columbia Valley housewife June Berg won—and almost lost—a fortune a month later.

For nine years, Mrs. Berg had used an old armchair bought in a secondhand store. Finally, she purchased two new chairs and asked son Archie, 13, and daughter Lenoa, 9, to burn the battered relic. Archie and Leona obediently complied. Hours later, another daughter, 14-year-old Carrie, asked Mrs. Berg “why I was burning Leona’s play money.” In Carrie’s hand were the charred remains of a $100 and $10 bill.

To Mrs. Berg’s horror, she recognized the currency to be genuine, although old. Ransacking the singed corpse of the armchair, she found $1,100 in bills. Some were so old they showed the portrait of Sir John A. MacDonald, Canada's first prime minister; the others were of King George V or George VI, it not being stated which.

Hastening to the bank with her blackened treasure, Mrs. Berg received just $412 in exchange, due to the fact that most of the bills were so badly burned they lacked necessary signatures and serial numbers. However, according to one news report, “the $412 was useful—it was spent on house repairs.”

But it would be a long, long time before the Berg family ceased to wonder, wistfully, just how much money actually went up in smoke!

Years ago, Margaret Williams wrote in the magazine section of the Victoria Daily Colonist of the history of Strawberry Vale district, a west Saanich suburb. Among anecdotes she told was the story of the old Rowlands Hotel, once situated at Burnside and Admirals Road. “There were many navy lads who had an account at Rowlands’ and it is said that one, who was plowing to work off a debt at the hotel, found a buried cache of gold pieces which were subsequently claimed by the proprietor.”

If local legend is correct we can but wonder who hid the treasure and when. And wonder, too, if, perhaps, there’s more there yet!

Some treasures can be deceptive in their appearance and usually require that their finder have some expertise. (You can always ask an expert!) In 2006 one of the most collectible books ever published on photography (Man Ray's Photographies 1920-1934) turned up in Saanich's Hartland landfill; it was retrieved by a man dumping off cardboard. He in turn sold it at a flea market where it was spotted by a rare book dealer who priced it, even in its somewhat battered condition, at $3500!

(You’re not allowed to retrieve items from civic garbage dumps or recycling centres any more, by the way.)

More recently, a Shawnigan Lake woman who spent 50 cents on a packet of Q-tips in a Duncan thrift store got considerably more than she paid for. As she later explained to a Times-Colonist reporter, “My eyes got big” when she opened the box. “I couldn't believe believe what I was looking at. I took out a string of pearls first, and when I did, all the rings started falling out.”

She returned them to the thrift store which re-sold them for more than $1000.

In 2012 a painting by the legendary Tom Thomson and a watercolour by Group of Seven artist Frederick Horsman Varley were purchased “on impulse” by an unidentified man (he chose anonymity) who took them to Maynard's Auction in Vancouver. They valued the Thomson painting at between $150-$250,000 and the Varley at $4000 to $6000.

Others have uncovered treasure, although not as easily.

The late Victorian and veteran prospector Charles Morgan found his pot of gold at the end of the rainbow in the Kettle Valley. “A CNR patrolman, George McInnes, told my partner and me of an old prospector who had been burned to death in a brush fire several years earlier,” Mr. Morgan recalled. “He said this old man used to pack out gold nuggets. McInnes knew where the fellow’s cabin was, and had been up that way once himself, but his legs were bad, and the country rugged so he hadn’t returned.

“He said there was a canyon with a wire rope running across it above a waterfall, which dried up somewhat in the summer. Anyway, after about a nine-mile hike, we found the old cabin. At the back of the shack was a pile of stones from the creek, which had been piled neatly. My curiosity got the best of me, as many of these old-timers hid their valuables, so we pulled the rocks apart.

We found two two-pound jam tins. Both were quarter-full of nuggets. They were smooth, meaning they’d been carried a long way by the river. We sold them to a bank in Vancouver, and we got a few hundred dollars for them.”

Mr. Morgan later returned with another partner. This time they were equipped with 30 feet of half-inch rope to string across the waterfall, the suspected source of the miner’s treasure. “But the day we got there, it rained and rained, and rain in that country is beyond description. So we returned to Vancouver and, of course, [his partner] went one way and I another. I’ve never been back but someday I’ll return. I’ve asked about, and don’t think any claims have been filed in there.”

(When I knew Charles Morgan he was retired in Victoria; to my knowledge he never did make it back to the old prospector's rich claim.—TWP.)

Mr. Morgan, who'd hiked over many miles of rugged British Columbia terrain in his search for elusive metals, even had a crack at the fabled ‘Lost Creek Mine’ of Pitt River. Surprisingly, he never searched for a considerably more accessible “lost lode,” near Vancouver Island’s historic Leechtown.

“One day, a couple of years ago, a fellow, who also worked at the shipyard, brought some ore samples to me. I asked him where he got them. He said, ‘Oh, I was out fishing and just picked them up.’ He’d found the samples somewhere near Leechtown. He had three or four pieces of chalcopyrite—copper. It was beautiful stuff, high-grade. I asked him if he could find the spot again and he said, ‘I’ve no idea. I never even thought about it, just picked the stuff up because it’s rather attractive.’

When not rainbow-hued as in the first example, chalcopyrite, copper, is often mistaken for iron pyrite—fool’s gold. --www.irocks.com

“It was really nice stuff, beautiful stuff—at least worth further investigation.”

My point is, you don't have to search (not always, that is!) rugged mountain peaks or brave lethal blizzards in quest of treasure. To give another example:

Victoria’s Hillside Farm, once owned by John Work of the Hudson’s Bay Co., experienced a minor rush in the 189s. Reported the Colonist: “The gentlemen interested in the development of the Work Estate quartz claims met the property owners yesterday, but failed to arrive at any satisfactory arrangement with them.

“One of the property owners submitted the proposition that they be let in as equal shares of the profits, but exempt from all assessments. This did not meet with the approval of the would-be miners, and it’s possible that the disputed points will have to be disposed of in the courts.”

(I was going to do a little prospecting of my own at the provincial Department of Mines to see if they have record of the controversial claims’ locations, but never got around to it even though I can now do so from my own library.)

I also wanted to find the long-ago Victoria address of a Mrs. Benjamin Gonnason, who discovered a gold nugget “the size of a small white bean” in the crop of one of her black Minorca hens. When the hapless hen had stopped laying, Mrs. Gonnason had promptly decided to make it Sunday’s dinner. While preparing the stew, she found the nugget. As the hen had been hatched on her property, and had never left the yard, Mrs. Gonnason naturally deduced that “there may be a gold mine about the property.”

Upon publication of this incident, in 1970, Mrs. Gonnason’s daughter had telephoned me to reminisce about the exciting hunt, and recalled, “We found no more gold—but the chicken was certainly good!” The mysterious source of the nugget, she had to conclude, had been the chicken feed.

Ten years before Mrs. Gonnason’s adventure, one William Miles of Alberni had made himself something less than popular by exercising his rights as a miner, choosing to stake his claims smack in the intersection of Government and Courtney Street in the heart of downtown Victoria!

Even in 1897, these were busy thoroughfares and Victoria City fathers understandably frowned upon the enterprising prospector’s attempts to dig a shaft underneath the shining new post office.

This amusing state of affairs had begun days earlier, upon Miles’s arrival in the city with a shipment of ore from his up-Island properties. While waiting for a streetcar, at the above-named intersection, he sat on the wooden sidewalk, idly glancing about. Suddenly, his eye caught the winking of yellow in a rock outcropping beside the road.

Upon investigating, Miles found, much to his amazement, that the tiny reflection was caused by gold and, upon looking closer he could see that the entire outcropping was mottled with the golden flakes. He wasted no time in staking his Douglas Claim (as he christened it), then set to work at convincing city council that he should be allowed to excavate. Officials, however, were adamant: the cost of surrounding real estate was considerably higher than the estimated worth of his claims.

Miner Williams miles wanted to dig up Victoria’s new post office! --Flickr.com

Miles’s claims had extended from the waterfront to Government Street. Said Charles Hayward, who claimed to have told Miles of the ore: “I saw the gold in the rock originally as I was walking over it, and having my glass [an indispensable aid in those days—Ed.] in my pocket, I at once examined the stone carefully, the free gold being plainly visible. The ledge is, too, a well-defined and properly placed one, for it has been traced to the water’s edge, on Wharf Street, a distance of 200 feet from the discovery post.

“I saw specimens today from the waterside, well mineralized but not of equal value with the samples from the location point, and not sufficiently good to justify the expensive operations that would be necessary to development.”

Among the “expensive operations” that Mr. Hayward had in mind was a rough estimate of the local real estate’s value: $350,000 [which you probably multiply by 25 for today’s value—Ed.]

Poor William Miles never managed to mine his bonanza, but he did prove my argument:

Gold is where you find it, sometimes even under your very nose!

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.