Charlie Cogger’s Tom Sawyer-style Summer on the Cobble Hill Frontier (Conclusion)

As I explained last week, every blue moon the Mountain comes to Mohammed.

By which I mean that a story, fully researched, comes to me.

Such is this week’s tale by Robin Garratt of England. In 2010, by which time he and his wife were in their 70s, they visited the Cowichan Valley for two weeks. Robin wanted to learn more about his maternal grandparents’ brief employment at Hill Farm in Cobble Hill just prior to the First World War.

Dave and Beth Keith, proprietors of Sahtlam Lodge B&B, very kindly passed the Garratts on to me and Robin shared with me the part of his family history that pertains to the Cogger family’s sojourn at what’s now 1200 Fisher Road.

The young English dairyman and his family travelled halfway round the world to an outpost called Cobble Hill that they couldn’t even find on a map.

Mr. Garratt’s father, Charlie, who was seven years old at the time, later recalled that adventurous time in his life. Here’s how he remembered their stay at Hill Farm...

* * * * *

Children enjoying a ride on a hay wagon. Too soon they would be old enough to help around the farm.

Archie, despite his initial reluctance to return to school, never played hooky, having developed a crush on the young teacher who allowed him to pass out and collect the text books. Nevertheless, said Charlie, Archie “still wanted to demonstrate to himself and to anyone near him that he had grown-up capacities”. After announcing that he'd found tobacco leaves, he attempted to roll a cigar between his palms from a “small sheaf of leaves in various shades of yellow, fawn or brown...but most were too brittle and crumbled to pieces. However, with a few more limp reinforcements he presently ended up with something approximately cigar shaped, put one end in his mouth, produced one of his phosphorous matches, and lit it.“

He puffed away energetically, stifling as far as possible his involuntary choking and coughing. I watched him with some admiration, and this egged him on to further proof of his manhood. He tried to swallow a mouthful of smoke so that he could then blow it out in a manly cloud. However, he got no further with the demonstration for his stomach revolted at such mistreatment, the 'cigar' disintegrated and dropped from nerveless fingers, he changed colour and exploded with an interesting mixture of coughing and vomiting.

“He reached out to steady himself against a tree trunk but bent over and slipped down to the ground.

“I became alarmed and went over to his shaking body as he lay on the leaves, his face a greenish-white, his fingers twitching, his eyes glazed, half-closed and unseeing. I felt he was dying, and tore off down to the ranch till I saw George [and] panted out that Archie was dying. He came at once but when we had climbed to where I had left Archie prostrate, he was sitting up though looking very sorry for himself. I explained he had found some tobacco leaves and smoked a home-made cigar.”

“Tobacco?” asked George. “There's no tobacco here. Show me the leaves.”

“I found some shreds of the leaves, part of which were burnt. George looked at them carefully and then found some whole ones like [them].”

“Are these the ones?” he asked. “Yes.”

“They're poisonous! It was lucky he was sick before he was poisoned. Archie, don't you ever do such a thing again!”

Then George grinned: “I don't think he will, either.”

“Don't tell Dad about it, will you, George?” Archie pleaded. George agreed in exchange for Archie's promise never to do such a thing again.

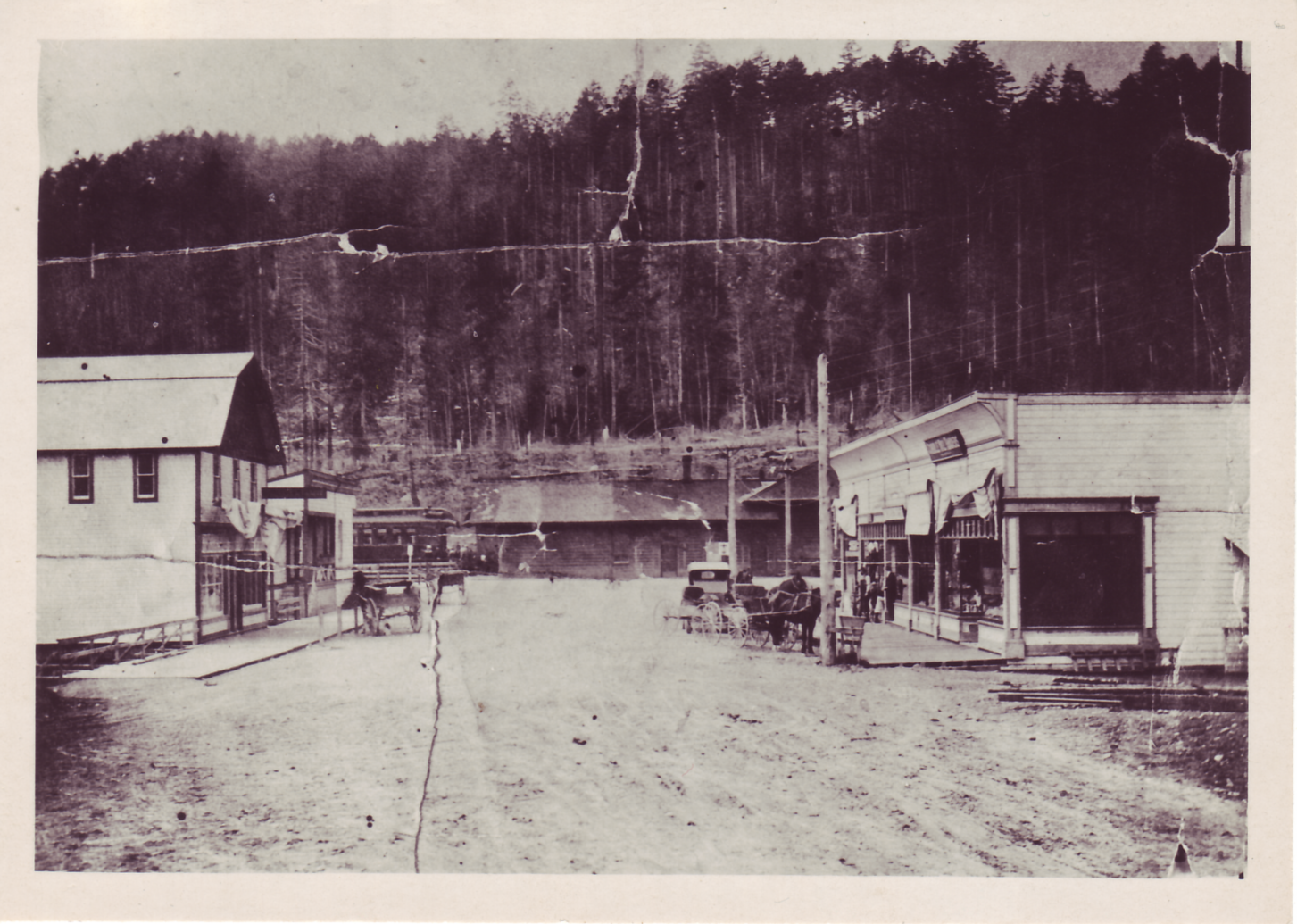

The Coggers couldn't even find Cobble Hill on a map!

And so the pact was made, with Charlie as witness, and, so far as he knew, kept.

On Matson's orders, the work of clearing the land continued; more fields meant more hay for more Jerseys. To do this he hired a contractor who brought in a gang of Chinese labourers, complete with their own portable bunkhouse. The first day they began work, the children, intrigued by their appearance and “sing-song” speech, were irresistibly drawn to their bunkhouse and peeped inside. “We were surprised that their hut looked empty except for the wide wooden shelves around the walls on which they apparently slept. Blankets were neatly folded at the end of each shelf and what intrigued us most, at the head of each space, was a block of wood where we would have a pillow. Part of the block had been hollowed out as if for the neck, and we marvelled that they could sleep so uncomfortably...”

That was as close as they dared come to these transient workmen whose alien appearance, speech and customs fascinated and repelled them at once.

Steadily, unrelentingly, they made the forest retreat, leaving just a waist-high stubble of stumps to be dealt with later. Charlie continues: “Every so often would come the only English word we heard from them, a long drawn-out 'Tim...ber,' the sound taking so long to cross the valley that the tree was over and down by the time we heard. Sometimes we would look and see a tree moving...then accelerate to a tremendous crash and crackle of broken branches. Then axe men would walk down the length, trimming branches from the trunk, which were collected a good distance away from the forest and burnt in a great bonfire. The clean trunks were collected separately and carried away.”

Particular care was given to burning the debris during the summer for fear of starting a forest fire but, one hot day, not even George's precautions sufficed. “It started spontaneously,” George recalled. “Elsie was looking down the long vista from the ranch house towards where the men were working, and saw a small tongue of flame at the foot of a tree at the edge of the forest, a little to the left of the tree fallers.”

“Look!” she said, pointing. “I think that's a fire.”

“We scrambled up and ran towards it, for we knew we must give the alarm before it got out of hand. We shouted, but the men went on working. Then a small flame, like a squirrel, ran along the ground to the next tree on the right, as if it were alive and purposeful, and knew where it was going. The second tree burst into flame, and we yelled as we ran. Just then came a shout and the men stopped what they were doing and ran with shovels and sticks and anything they could lay their hands on. Their high-pitched gibberish [sic] was soon smothered in the crackling and roaring.

“Fortunately, there was no wind, and they managed to contain the outbreak by pouncing on flames, branches and pieces as they fell, and [the resulting] sparks. The fire seemed to lose its appetite. Most of the men went back to their jobs but they left four or five at the two trees that were burnt to watch for, and beat out, the life of any squirrels of flames that tried to escape. Soon the trees were blackened masts, gaunt reminders. [By] next day [they] had cooled, were cut down and burnt in the bonfire.”

Even more exciting for the youngsters was the blowing up of the stumps.

After scooping several holes around the base of a stump the foreman packed each hole with sticks of dynamite, ran wires to a detonator and put the soil back in place. From a safe vantage point Charlie watched, wide-eyed: “When he was satisfied he gave the word and the Chinese scampered around, yelling, and all withdrew. Then the [foreman] pushed the handle down smartly, and there was the most glorious group of explosions.

“First we would see the earth and stumps open up and lift skywards, breaking up as they went. They were chased by orange-coloured flames and smoke. Each stump-site produced a fountain of dirt, rocks and pieces. Then came the shattering roar of the explosions...then the rattling and thumps of debris falling around, the bigger pieces bouncing satisfyingly.”

But it was while he was exploring the woods on his own that Charlie had his most memorable experiences, the last one all the more so as it could have proved deadly. That afternoon, another afternoon of playing hooky, began idyllically with his seeing and following a butterfly in the hope that it would land and allow him a closer look. He could scarcely believe that such a beautiful creature could have begun life as a lowly caterpillar.

“Now it airily zig-zagged and danced away through the shafts of sunlight, and seemed to belong more to a fairy world...

The butterfly settled momentarily on a flower, and I crept up holding my breath; but it saw me coming or was disappointed in the flower and danced off with a burst of speed that left me standing. Five or six yards away it paused and danced derisively and was gone.

“I looked round and suddenly realized I had not the slightest idea where I was, nor in which direction home lay. I moved on again and crossed a forest track, dry, dusty and rutted. I had hardly made up my mind to follow the track, one way or another, when there was a snorting, crackling, rumbling noise, growing bigger and more frightening as I listened. I looked around for safety, for whatever it was, it was certainly approaching along the track. Just off the road I found a tree with low horizontal branches and scrambled up as high as I could. I had to bend and wriggle this way and that but there were plenty of close-paced steps and I was 10 feet up and safe, I thought, when 20 or more cattle came stampeding along the track, churning up the dust, tossing fearsome horns, wild-eyed and flecking strings of foam.

“Those at the back were jostling those in front, and occasionally one would ride over the hind quarters of another. They passed beneath me and I tightened my grip until my fingers ached. Without pausing they receded along the track and turned a corner and were out of sight. I could still hear them, but the sounds died away and presently the silence of the forest crept back. I never found out whether they were wild or belonged to someone and had escaped or what... There was no [one] with them.”

Only when he was certain that they were gone did he climb down.

But now the dirt lane through the trees “seemed to me to be a dangerous place, and I struck off through the forest at right angles to it. There was much to see and I was not unduly alarmed at being lost, for I thought I would be bound to come across some dwelling sooner or later, and they would direct me. In addition, the relief I felt from avoiding damage from the cattle made me buoyant. I walked on, sniffing the pine-laden air with relish. There was so much to see, so much that was still strange and different from Epping.

“A different smell mixed with the forest smells and I quickly recognized it. It was the smell of the sea. [Satellite Channel, probably just south of Cherry Point—TWP.] The trees thinned out and I found myself on a low cliff of bald rock overlooking a blue calm sea, with green pine-covered islands with lace-trimmed petticoats and, beyond these, a broader sweep of sea backed by distant mountain peaks. To my left the cliff rose higher and at its foot was a dark, pebbly shore, with here and there grey-white tree trunks lying askew like the carelessly strewn bones of a pre-historic monster. In this setting anything seemed possible.

“Just floating at the edge of the sea below the grey trunks were darker, fresh tree-trunks huddled together. I did not understand this and scrambled down over rounded rocks to the pebbles to have a closer look. I made my way along, slipping and stumbling on the dark, wet, smoothly-rounded stones that made up the beach. When I reached the log raft I found the logs were just floating in shallow water and I could wade out, I reckoned, to the nearest without getting wet higher than my knees.

“This turned out to be a miscalculation.”

(At this point in his narrative I feel compelled to remind readers that Charlie was then just seven years old and a stranger to the comparative wilds of the Cherry Point area. He was not only alone and lost in an unpopulated area but, because he was supposed to be in school, no one knew even where to begin looking for him once his absence was noticed. On this particular afternoon the cattle stampede proved to be only an introduction to danger...TW)

Charlie continues: “Folk memory of over a million years past now stirred me into action. I re-enacted the discovery of primitive man; I scrambled cautiously onto the nearest log and re-invented the boat. The log bobbed slightly and shifted sideways, uneasily, like a friendly cart-horse who is not used to having anyone on his back. I liked the feeling of buoyancy but at the same time felt insecure. I clung with hands and feet and knees, and kept very still. Things settled down and I moved gingerly along the trunk. There was another log floating athwart my log at the far end of it and I inched my way towards it. Presently, I was near enough to venture a transfer.

“But this demanded that I stand up in order to step across.

“As I straightened up I must have shifted my weight, for the log slowly started to turn. This was treachery! Panic clutched me. I leaped. And the moment I landed on the next log I knew I had done the wrong thing. This log, too, came alive, shrugged slightly and began to turn; but this one, askew, turned in a different plane direction, confusing my apprentice sense of balance. There was a wild waving of arms, a lifting of one leg as counter-balance, a slipping of wet leather sole on hard tree-bark, and I learned painfully the abrasiveness of rough bark on tender shins. Mercifully, as I dug my fingers, cat-like, into the crevices and froze in horror at impending disaster, the log stabilized and I could breathe again.”

Here, he interrupted his narrative to leap forward by 58 years when, on holiday in British Columbia, he attended a Loggers' Sports Day in Squamish. Watching professional log-rollers compete “triggered...memories of my first and only [log rolling] efforts at Cobble Hill. I re-lived the thrills and felt my nerve-endings tingling.”

As for that memorable afternoon, however, he'd had enough thrills for one day.

“The deepening shadows urged me to get ashore and go home... I don't remember how I got ashore—only that I did. I turned into the forest and made my way with the sea at my back... I was incredibly lucky. I found the track and crossed over it at right angles and pressed on. For some minutes I went on, trying to remember where the sun was when I came, and making allowance for its changed position with the passing of time. But I had no idea how long had passed. I was hungry but this was normal... I was getting worried when I smelled burning wood. The smell permeated through my body and strengthened my weary limbs. My clothes had dried on me, and when a few minutes later I broke free of the forest, the tree-felling gang were a short half-mile away, and the ranch house stood our clear and toy-like across the valley, and the finger of blue smoke from its chimney beckoned a relieved adventurer.”

“You're late, Charlie,” said Mother. “Did you have a good day at school?”

“I walked a bit in the forest,” he carefully replied. “I saw a dear little chipmunk.”

If this all sounds a little bit Tom Sawyeresque, it was.

But, already, ominous shadows were forming on the Cogger family's new and happy life in the New World. Back in Europe, in a little-known country called Serbia, the assassination of an arch-duke and his wife proved to be the spark that culminated years of growing political tension between Great Britain, its world-wide empire and allies, and Germany and its allies. Not even distant and diminutive Cobble Hill was immune.

“We children were all at school when the news reached our back-water. The train arrived at the depot with continuous clanging [of its bell] which normally would have stopped as soon as it had made its regular announcement of the train's arrival. The clangour continued feverishly, until it was clear that something was up. Shouts rang out which penetrated the school log-house and the teacher being as curious as we were, closed school abruptly, gathered together her belongings without bothering to clean off the blackboard, and hurried off to find out. We beat her to it.

“At the depot the train was still hissing importantly, and the fireman was still hauling vigorously on the bell rope. Union Jacks had been tied on to the front of the engine, the driver was leaning out of his cab and talking to the people below who lifted their faces and listened. Late arrivals joined the back of the small crowd and asked others what it was all about, and some were retailing to the newcomers what they had just heard, and some were asking the driver afresh for the news they had not quite understood. Then there was a general cheer, and we finally understood the excitement:

“'Britain is at war with Germany!'

“We [children] didn't see what this meant or how it could affect us, the but the citizens were enthusiastic, and proud that Britain was once again about to assert her authority. Most of them were immigrants from Britain, or descendants of such.

“We took the news home and Dad was hard to convince. Then he thought that this was so far outside our experience that we could not have made it up. He got out the buggy and drove into town to find out for himself, and a long time later, came back looking grave and thoughtful. We were sent to bed early that night and when Mother came to say goodnight her eyes were shining.

“Next day we didn't go to school. Dad said soberly that he would have to give up the job, and we would all have to go back to the Old Country to help fight her enemies. The patriotic fervour of the South African War had permeated his being when he was young, a substantial residue remained and emotions overpowered reason.

“He arranged the sale of the furniture which had only arrived three weeks earlier, including the piano that Mother prized because her father had given it to her.

“But settlers locally had little money. Bidding sagged because it was clear that the stuff would go anyway, without reserve. The piano went for five dollars, and this cheapening of her childhood's darling saddened her more than its loss. Years afterwards, I heard her regret that she had not left it in England in the care of her sister, Mary.

“Dad gave in his notice, without weighing the sacrifice, jettisoning our hopes for a bright future in Canada. Mr. Matson both regretted and admired [his] decision. Everything seemed to happen in an undignified scramble [but] the war excused unusual behaviour.

“We found ourselves once more homeless, took [the] train to Victoria, thence by ferry to Vancouver, then endless waiting while Dad disappeared into offices, hurried meals in restaurants and a pervading sense of uncertainty...”

For all his willingness to serve, James Cogger didn't make it into the army, developing pancreatic cancer and dying in 1920.

The outbreak of war shattered the Coggers' colonial sojourn. Cobble Hill, Hill Farm and Sam Matson would become little more than distant and fleeting memories but for the impressionable Charlie who, most of a lifetime later, with the help of sister Elsie, would eloquently recount his childhood adventures for future generations of the family.

Hence, in 2010, the visit to the Cowichan Valley by the Garratts, as Robin sought to learn more about the maternal Coggers' brief stay. Hence, too, through Sahtlam Lodge B&B, his graciously sharing with us this fascinating glimpse at a way of life long gone and now alien to those of us who live in the Cowichan Valley today.

Charles Cogger's gift with a pen shows vividly in his memoirs, a skill he appears to have honed during his professional career. His father's premature death left his mother with four young children and little in the way of money. Charlie's contribution came in the 1920s when he became old enough to join the army. In 1939-1945, Robin tells us, Charlie was the Official Shorthand Writer to the Director of Military Operations in the War Office. This post allowed him “the most fascinating insightful career at much of the top-level goings-on at the war cabinet in their bunker under Whitehall, accompanying his military bosses and Churchill to Washington, Yalta and so on...”

It also earned him the honour of an MBE (Member of the British Empire).

“After retiring as [a private school] headmaster he set out about his memoirs, until the onset of senile dementia. Many years after he died I had access to a bundle of his carefully typed foolscaps, but muddled up in several carbon copies of several different drafts with much missing.

“I managed to get this into a reasonable order for distributing to the children, family, etc.”

Robin's one regret was having not found anyone home in 2010 when he and Carol popped in at 1200 Fisher Road which has been owned since 1938 by the Baird family. What a shame; Margaret Baird, a lifetime stalwart of the Farmers' Institute and the Cobble Hill Women's Institute, would have been pleased to answer his questions and to have learned something more of Hill Farm's pre-Baird history. Now Margaret Ellen Baird is gone, too, having passed away in May 2017.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.