Chronicles Mailbag Adds to Story of Notorious Outlaws

One of the joys of publishing what really amounts to an online magazine is that it often draws a response from readers, usually as brief comments but, sometimes, something much more ambitious.

In my previous life as a weekly columnist in the Cowichan Valley Citizen, I condensed a chapter from my book, Outlaws of the Canadian West, which is a compilation of new chapters and ones originally published in 1974 as Outlaws of the Canadian Frontier then, again, in 1977, as Outlaws of Western Canada. (Don’t tell me I don’t recycle.)

Fast-forward to 2019 and its third incarnation, as explained above. But it was my weekly Chronicles column in the Citizen that drew a wonderful email from John McNab.

I’d been inspired, if that isn’t too strong a word, to run the story, entitled “Intensive Manhunt isn’t B.C.’s First,” by the fact that for two weeks the news media had been reporting a murder spree by two Vancouver Island teenagers who first were thought to be among the victims, then identified as the killers.

It reminded me of another manhunt that dated back to 1911 which I’d written about in Outlaws. The story of Moses Paul and Paul Spintlum is right out of the Old West, when the British Columbia frontier was almost as wild as the American frontier, the only real difference being that of law and order. We to the north of the 49th parallel had British justice, the RCMP and the Provincial Police as opposed to the Hollywood-style mayhem that prevailed to the south.

For no less than 18 months provincial police searched for Moses Paul and Paul Spintlum whose amazing saga began in the summer of 1911 in the appropriately named Suicide Valley, south of Clinton. The manhunt ultimately involved 100s of men, criss-crossed 100s of square miles of range land, cost untold 1000s of dollars and five lives.

It began at the shack of an elderly Chinese woodcutter and gardener named Ah Wye, on the historic Cariboo wagon road, just outside Clinton. On the hot afternoon of July 4, teamster William White (also referred to as Alexander Whyte), arrived at Ah Wye’s to buy eggs. A third man, Charlie Haller arrived with the same intent, when all were joined by 25-year-old, mustachioed Moses Paul (also called Coxey Mowie) of the local reserve.

White, Haller and Paul shared a drink then left Ah Wye’s for Suicide Valley to consume the rest of their bottle.

The next morning, teamster Louis Crosina, passing through the valley, discovered White’s battered body. When Provincial Police Constable John McMillan reached to the scene, he saw that White had been beaten to death with a blunt object. Although he found few clues at the scene, he had no difficulty in tracing the murdered man’s last movements and soon learned of his drinking bout with Charlie Haller and Moses Paul. It seemed likely that, after emptying their bottle, the three men had quarrelled and fought, either Paul or Haller – or both of them – having ended the argument with the bloody rock found beside the body.

McMillan arrested Haller, then proceeded to Paul’s shack. When a search of the cabin uncovered White’s watch he was charged with murder and locked in the decrepit Clinton jail with Haller. Brought before Magistrate Saul, both men were twice remanded. On August 12, Haller was released but Paul was remanded a further eight days.

It’s at this point that the script went awry, when McMillan over-estimated the security of the Clinton lock-up—and worse—forgot about Moses Paul’s erstwhile friend, Paul Spintlum. The stocky Spintlum, in his 30s, would quickly prove to be not only loyal but lethal, the authorities soon learning to their regret that he possessed daring and determination.

Spintlum had a file smuggled into the jail in a baked salmon and Moses Paul soon rasped his way to freedom. On August 15, they fled from Clinton and one of the most trying manhunts in Cariboo history was soon underway.

First they made a stop at the cabin at Ah Wye. It had been the old woodcutter who’d linked Paul with White in Suicide Valley, and, convinced that, with him out of the way, the Crown had no case, they, split his head open with his own axe.

At least so the police surmised although the coroner’s inquest was more circumspect in ruling that Ah Wye died as the result of “a blow of an axe, inflicted by a party or parties unknown”. The authorities, sure of Paul’s guilt, intensified their efforts to apprehend both fugitives who, they knew, had good horses, rifles and ammunition.

Constable McMillan and his posse know they were up against two expert woodsmen; other than a few moccasin tracks about the murdered man’s cabin, there was no trace of them. Moses Paul and Paul Spintlum had vanished.

As retired Deputy Commissioner Cecil Clark of the British Columbia Provincial Police noted half a century later: “…As successive generations of Cariboo lawmen will testify, it’s no easy matter to run an Indian [sic] to earth in that part of the world. Especially if he has friends to supply him with grub and fresh horses. You can couple this to the fact that no foxier pair existed than Paul and Spintlum.”

Despite healthy rewards ($1,000 for Paul, $500 For Spintlum) offered by the authorities, come the spring of 1912 they were still on the loose.

By then, Constable McMillan had been replaced by Constable T. Lee of Savona who, in turn, had been replaced by “Mr. A. Kindness, late of the Vancouver Police Force [sic[,” as reported by the Ashcroft Journal” on Dec. 23, 1911.

It was months later, on the morning of May 3, 1912, that ranch hand Charles Truran stumbled into the wanted men’s camp. (We’ll come back to Mr. Truran in due course.) According to the Journal, Truran had immediately recognized them but he pretended to be unconcerned and “managed to leave their camp without arousing their suspicion” and galloped back to his employer’s ranch to raise the alarm. Alerted to the outlaw’s campsite,

Constable Kindness and a five-man posse headed for the Pollard ranch, Kindness was accompanied by Constable Forest Loring and civilians George Carson, James Boyd, Bill Ritchie and Charles Truran, At the Pollard ranch, Charles Pollard and his son John assumed the place of Truran, who, fortunately as it turned out, had decided to retire from the chase.

Despite its being “heavy brush country,” the posse steadily gained on the fugitives and, after six miles, overtook the pair’s abandoned horses and camping gear.

Kindness, rifle in hand, and Loring approached the animals first, the others following just behind them on the trail. Suddenly, one of the outlaws fired from his hiding place behind a log, the bullet slamming into Kindness’ chest. According to the astonished Loring, his colleague doubled up in his saddle and, hands clutching his chest, cried, “Oh, you beggar!”

Amid a volley of shots, Loring whipped his horse around and retreated for cover then leapt from his horse just as a bullet shattered his forearm. From the shelter of a tree, although wracked with pain, he drew his revolver and returned the outlaws’ fire and when one of them jumped from behind his log, he charged after him, firing as he went.

“The posse,” reported the Journal, “were scattered in the dense brush and although several shots were fired at the murderers none took effect. On returning to the place where they were ambushed they found young Kindness laying on his back, stone dead. He had been shot through the heart. It was useless to pursue the Indians in the dense foliage covering the hills, so the party divided, some staying to watch for possible signs of the murderers whilst the others came to Clinton for reinforcements.”

Not surprisingly, word of Kindness’ murder threw the town “into a great state of excitement,” it being reported that the young Scotsman, who’d been assigned to Clinton but weeks before, had been “a fine specimen of manhood and deep regret is felt amongst his friends at the sudden taking off of such a promising young officer”.

A fresh posse returned empty-handed from the ambush scene as Chief Constable W.L. Fernie arrived from Kamloops with a special detachment of Indigenous trackers who’d participated, several years before, in the hunt for the notorious American train robber Bill Miner. It was generally accepted in Clinton that it would take at least “30 good men” to catch the killers who’d obviously been helped with food and ammunition by their friends. It was also believed that Paul and Spintlum would fight to the death when cornered.

By this time the provincial government had increased the rewards to $3,000 for both men ($1,500 each, Spintlum now enjoying equal billing with Paul). Constable Fernie’s first move was to arrest all relatives and friends of the fugitives, thereby reducing their hopes of securing further help and provisions.

Then Fernie and his squad of veteran trackers hit the trail. For three wearying weeks they dogged the outlaws’ movements, as Paul and Spintlum tried everything they could to throw them off. Slowly, the posse gained on them and the murderers were forced to abandon much of their equipment and supplies to make better time.

Despite such tactics as their separating, utilizing the tracks of wild horses, and reversing the shoes of their ponies, the posse held on and were right behind them when they reached Bonaparte Creek. But, at Kelly Lake, the killers reached harder ground and their trail petered out. His trackers, for all their efforts, couldn’t follow farther and Fernie had to to turn back.

By Autumn, the manhunt had passed the year mark, with the outlaws still on the loose after two further killings. As 1912 neared its close, the authorities decided to enlist the support of the region’s tribal chieftains and T.J. Cummiskey, Inspector of Indian Agencies at Vernon “summoned together three Indian chiefs at Clinton” in mid-November.

Six months later, Cummiskey termed the pow-wow “one of the most important events in the year’s work,” recalling that he’d appealed to the tribal leaders “through a sense of justice and to their consistent belief in Christianity which I knew was implanted in their hearts by their missionary priests”. After considerable discussion, much of it heated, and after noting that “It is not good policy in dealing with Indians to make a display of physical force and to fail – moral suasion is a better weapon,” he convinced the chiefs to surrender the wanted men.

So it was that, on Dec. 28, 1912, after a year-and a-half of pursuit, Moses Paul and Paul Spintlum were taken into custody without a struggle. Their capture, after so many months of bitter searching, through wilderness and in the worst of weather, was anti-climactic. It seems that Indian Agent Cummiskey had employed something more than the “moral suasion” he’d mentioned, the Journal reporting that he’d given the chiefs the ultimatum that, if Paul and Spintlum weren’t handed over to the police by year’s end, their “official dignities as chiefs would be cancelled”.

Taken to Ashcroft, Paul and Spintlum were said to be “somewhat emaciated [but] not in such a deplorable condition as might be expected from long exposure and hardships, and as they quietly smoked their cigars in the waiting room of the Ashcroft Hotel they did not seem like the desperate criminals which they really are. The captives left Ashcroft on the 4:30 train for Kamloops, where they will in all probability await trial at the spring assizes.”

Their lawyer, Stuart Henderson (known as “Canada’s Clarence Darrow”), succeeded in having the venue changed to Vernon, where a jury listened to extensive and vivid testimony by the members of the ill-fated posse on the day Constable Kindness was shot. In the way of more circumstantial testimony, James Robinson said that he’d sold cartridges to Spintlum on the day that Paul broke jail. For all that, the jury disagreed and a new trial was ordered for the June Assizes at New Westminster.

This time the Crown offered overwhelming evidence and, on June 27, 1913, despite a “brilliant plea to the jury” by defence counsel Henderson, Paul Spintlum was found guilty of murder. Sentenced to hang on September 12, he went to the gallows at Kamloops on Dec. 12, 1913.

Moses Paul, who’d set the tragic chain of events in motion, was sentenced to life imprisonment, having been convicted on the lesser charge of accessory after the fact! Ironically, he might have been better off being hanged, as he soon succumbed to tuberculosis, thought to have been contracted during the 18-month-long ordeal on the run in the bush.

There’s a revealing footnote to the tragedy.

The province struck silver medals for the chieftains who’d been instrumental in surrendering the wanted men to justice. They, however, resolutely refused to accept the ‘honour.’ With that, after an argument with Agent Cummiskey as to the original terms of their agreement to turn in the fugitives, the amazing saga of Moses Paul and Paul Spintlum was, officially, closed.

It’s quite a story, I think you’ll agree, my memory of it being twigged by the recent manhunt for the two teens. Which brings us back to my preamble about letters to the editor (me). Last April, John MacNab wrote, “I read with great interest your story ‘Intensive Manhunt Isn’t B,C.’s First’...

“A bit of that story has been passed down thru the ages through our family but no where the full story as you presented it. We are originally from Big Bar, BC about 55 km from Clinton and our great great grandmother Questoria Sapenac had a sister named Lucie Bones. On January 1, 1905 Lucie married William Truran who was the brother of Charles who, in your story, stumbled into the outlaw[s’] camp.

“As a side note, my great grandfather Serapio Leon had boarded with Charles at his place outside Clinton (on a lake, forget the name of it). Serapio worked for Cataline the packer as his farrier and cowboy.

“Here’s the notes I have from the family ‘bible’:

‘Some brothers killed a Chinese man for his gold. Then they killed the sheriff who was hunting them with his posse. Their camp was well supplied by someone and when they were caught, they had a list of people to kill. Lucie was on that list.’

“There are slight differences such as the Chinese man killed for his gold rather than revenge and the fact they weren’t really brothers. It has to be the same event because how many sheriffs [sic] were killed in that era in the Clinton area? It confirms a story which has been passed down but [is] hard to believe.”

John concluded his email with the obvious question, “Why would Lucie be on a hit list? That never made any sense and seemed like a tall tale...”

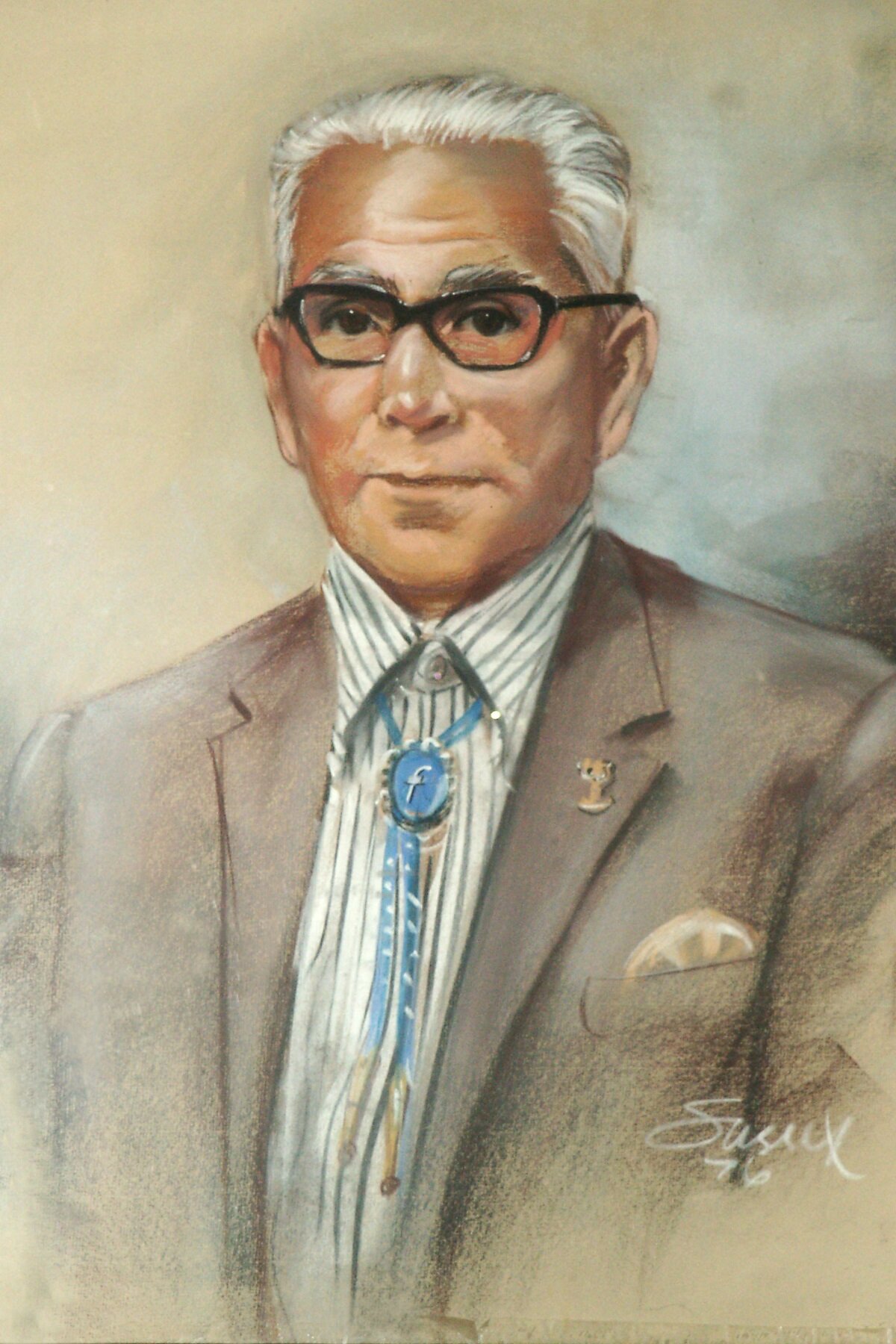

He also sent along a photo of Lucie Bones Truran, Charles Truran’s sister-in-law, who was born at High Bar in 1878. She died at Ashcroft, July 25, 1956 and is buried in Whispering Pines Cemetery, Clinton.

I thanked John profusely and asked if I could pass everything along to readers of the Chronicles. He graciously consented and here are the family photos with John’s captions slightly edited:

Lucie Truran

Lucie (Bones) Truran was born at High Bar in 1878; her maiden name was Elizabeth Violet Mary Bones. She had brothers Jacques (Felix) Bones, Joseph Bones (who was a mute) and a sister Questoria Sapenac (Victoria Hinck).

Lucie had a son Charles Augustus Richardson. Charlie was born in Big Bar, Dec. 14, 1903. Victoria and Elizabeth Hinck were in attendance at his birth. His birth was registered June, 1936. On the birth certificate it states that Lucie had four children, Charles Richardson, Rosie and Mary Jamieson and Lily and James Truran.

Lucie used to show her grand-daughter, Lila, a big white rock and said that was where Lucy’s father was buried. It was about two miles from Henry Hinck Jr.’s place. Lila and Lucy used to pick choke-cherries there. Lucie used to tell Lila about High Bar Flats where they came from.

Lucie’s son Charles Augustus Richardson

On May 27, 1911, Charlie started working for the Empire Valley Ranch. The store records show that he bought a pair of socks and a blanket for $6.50.

The Richardson brothers.

Charlie Richardson Senior is the fourth man from the left (holding the horse) in the back row.

Back to John MacNab: Charlie Senior died July 7, 1921. He was 56 years old. His death certificate said that he was English and that he was married. His occupation was listed as ranching at the Gang Ranch. He is buried in Ashcroft, B.C.

Lucie married William Truran Jan. 1, 1905. She was 27 years old and he was 49. His occupation was farmer. William was born in Cornwall, England. His parents were James and Mary Truran. The marriage certificate gives Lucie’s maiden name as Spenny and her parents were listed as Rousakrat and Brigette. William’s mother, Mary, died at Pollard[‘] Ranch on June 4, 1900. She died of pneumonia. Lucie’s husband William died May 2, 1908 in Kamloops. His profession was listed as a labourer.

Lucie and William had a daughter, Lily, and a son, James. Lily Truran was born January 13, 1905. Lily had a daughter Lila Grinder. Lily died December 13, 1938 from appendicitis and gallstones. She was working at the cannery in Ashcroft. Lila remembers Eddie bringing her mom’s body back to Clinton in the back of his old Model A Ford. She was buried in Clinton. Lily’s daughter, Lila, was raised by her mother Lucie and her brother Jimmie Truran in Jesmond.

Lucie’s son, James, was married to Agnes (maiden name Bill) and they had a son, William. Agnes died Oct. 15, 1969 at the age of 62. She is buried in the Indian Cemetery in Clinton. William was born June 8, 1937 and died Feb. 27, 1969. He was 31. William died of acute alcoholism, exposure with freezing on the Trail on Lime Mountain. James died in Kelowna, Aug. 31, 1980, age 72.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.