Cowichan Bay Pioneer Was the Original Neighbour From Hell

I’ve often wondered why some people seem hyper-sensitive to their family histories; sometimes to the point of burning old papers, photos and other memorabilia that should have been passed on to future generations.

Personally, I’ve often joked that if my great grandfather was hanged for cattle rustling I’d revel in the fact. (Think of it as colour!)

Well, a lady researching her family history approached me in October about one of her forefathers whom I’d written about, years ago. As it happened, a fellow scribe had just picked up on that very issue of the Citizen back when the Chronicles appeared there, so I forwarded her a copy of his post.

(It saved me having to dig into my files.)

From his post, which he based on my column, she clearly saw that her antecedent on her mother-in-law’s side of the family was both a cattle rustler and an attempted murderer whose chosen career as a frontier hellion was cut short by the dreaded ‘Hanging’ Judge Begbie.

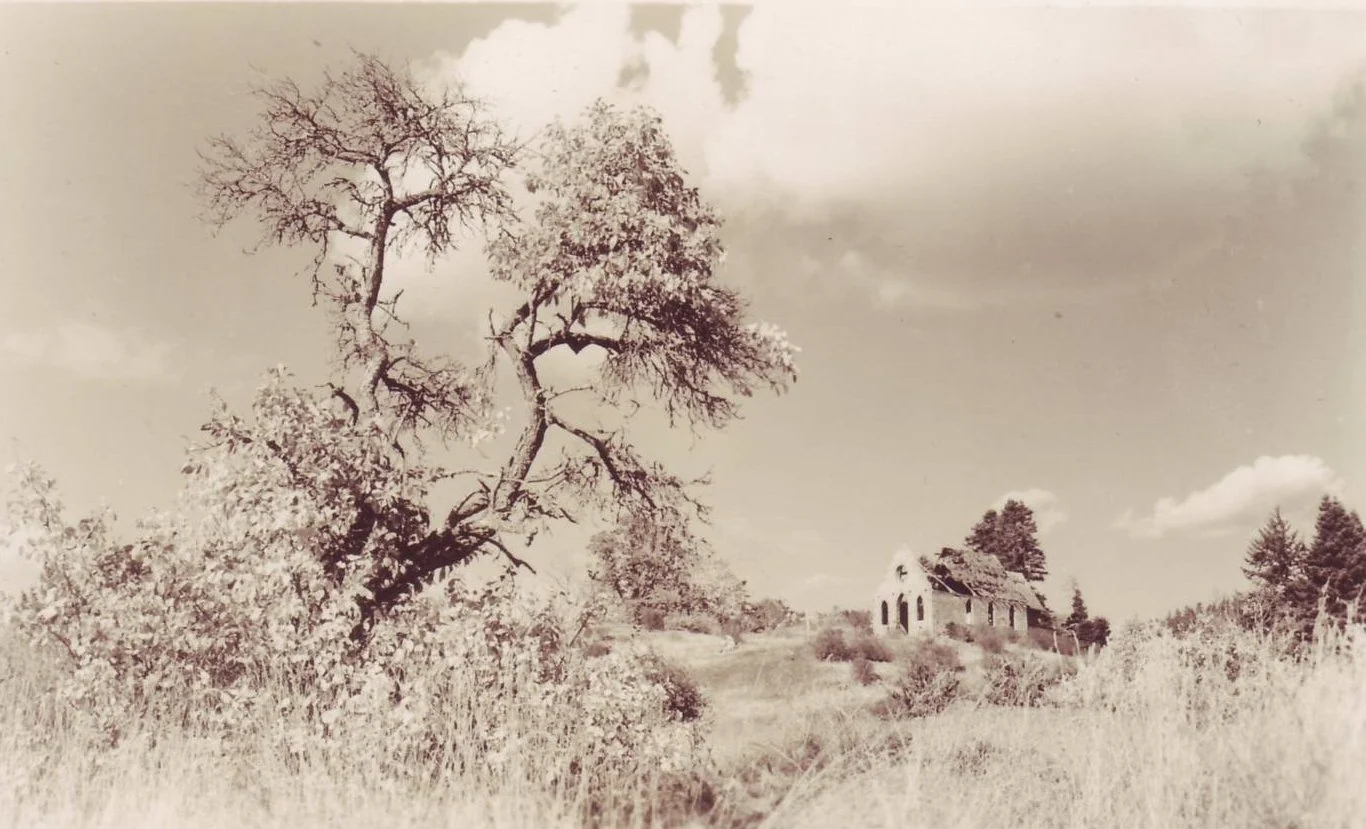

As if farming on the Cowichan frontier wasn’t challenging enough, having a gunslinging cattle rustler for a neighbour was salt in the wound! —Author’s collection

Rather than cringe with embarrassment, she wants to know more. I quote: “I was in the Cowichan Archives searching for a possible family member from the 1800s. In the file for Patrick Brennan were notes about articles you had written about him. As the latest Cowichan Citizen starts in 1996, these are not on newspapers.com.

“Do you have them on your site or anywhere else? I did not ask at the Archives as they were busy...

“My mother-in-law, soon to be 97, maiden name is Brennan and her grandfather was born in Wellington. I am finding connections to Patrick, but he was Brannen in this area, possibly because of his prison term. However, I am trying to see if there is a family connection as the properties abutted here to my Brennan’s in-laws.”

I’m going to leave it to Louise to confirm a definite link between ‘Brannan,’ ‘Brennan’ and her family. But I do have a file on Cowichan’s Patrick Brennan who made quite a name for himself in the 1860s as one of the Valley’s first white settlers.

Not a good name, as will soon be apparent.

* * * * *

Look closely; this isn’t a painting of the Butter/Old Stone Church but a great 1970s postcard by the late Duncan commercial photographer Charles Worsley. Patrick Brennan’s contested acreage was just beyond, to the right of the photo (west as the crow flies). —Author’s Collection

An Irish immigrant, he appears to have come to Vancouver island via Ontario and California; it’s known he and friend and future neighbour Tom Shaw were in Victoria in February 1859. The first reference I have for him is in the British Colonist, in August 1865. It’s tame enough—and certainly out of character. The letter to the editor is signed by L.L.B.

“Sir, among the many jovial parties of which I have been a partaker, I must say I never saw a more happy reunion than the one I attended last Saturday evening at the dwelling of Mr. Brennan. The house was neatly prepared with seats for the accommodation of all the settlers who were present in great numbers, and manifested the liveliest feelings of neighbourly joy and good fellowship.

“The dance was a long one occupying from seven p.m. until half-past six a.m. [!], with an interval of two hours, and was opened by Mr. Brennan who proved himself an expert at dancing break downs and waltzes. It would be lavidious [?] to mention the names of those who carried off the palm in the various kinds of dances.

“The only thing that seemed to be unanimously deplored was that the fair sex were few in number. But still all enjoyed themselves most heartily and we indulge hope of seeing one day in Cowichan an even proportion of each sex.

“When the company was about dispersing Mr. W. Smith [Cowichan pioneer William Smithe who later served as premier?] was called on for a speech to which he responded by remarking that it really did him good to see so many happy faces before him in Cowichan, and that such joyful meetings were a sure sign that Cowichan was progressing [?] and socially.

“In concluding he reminded them that they owed the joys in which each individual was participating to Mr. And Mrs. Brennan...”

The sun was well up when the party dispersed at 6:30 a.m., after a round of cheers for Mr. Brennan.

This is all so out of character with what we know about Patrick Brennan today as to suggest an almost Jekyll-Hyde personality. Certainly his immediate Indigenous neighbours upon whose reserve he’d encroached weren’t sharing or cheering his “neighbourly joy and good fellowship”.

(I should point out that, according to former Duncan mayor and MLA Kenneth Duncan, who wrote a retrospective article in the Cowichan Leader in 1935, Mrs. Brennan was Cowichan’s first white woman settler, having arrived in 1861. But not even The Pioneer Researchers, authors of Memories Never Lost: Stories of the Pioneer Women of the Cowichan Valley...have learned her first or maiden names.)

When next the Colonist mentions Mr. Brennan the other shoe has dropped, the headline reading, Shooting at Cowichan.

“On Thursday Patrick Brennan, a well known resident of Cowichan, was brought down from that district and lodged in gaol, under a warrant of commitment from Justice Morley, to await trial at the Assizes.

“Brennan and a farmer named Shaw had a misunderstanding about cattle, and in the altercation that ensued Brennan fired one shot from a revolver at the other man. The shot missed its aim and Brennan was taken into custody. A feud has existed between the parties for some months and both the parties were before the County Court at its last sitting –the one as plaintiff and the other as defendant.”

What a dramatic difference between these two accounts, five years apart—from genial host to would-be murderer!

The problems, not just with Shaw but with almost everyone around Brennan, go back to the very beginning when he squatted on tribal land just eastward and across Tzouhalem Road from today’s St. Ann’s Church cemetery, then demanded that the colonial government rubber-stamp his title to the land. None other than Bishop Modeste Demers made this plain in a letter in 1864:

“Mr. Brennan has been at Cowichan about four years. Since he has been there the Indians [sic] have continually complained of the harsh and unjust way in which he treated them and of the depredations committed upon their crops by his cattle and hogs.

“During last May, he shot a valuable dog in the supposition that it had killed some of his pigs. It was afterwards discovered that the pigs were all safe—when he shot the dog it was lying in a house and two women were sitting close by at the time.”

Read that again: Brennan, without foundation as it turned out, shot the dog inside its owner’s house!

The Bishop’s reference to depredations committed by Brennan’s cattle and hogs on his Cowichan neighbours’ crops wasn’t confined to him alone, however. It was a common problem throughout the Valley and continued for decades as is confirmed by newspaper reports that go well beyond the turn of the last century.

In short, few settlers, white or otherwise, wanted to be put to the expense of fencing in their livestock; with the result that their neighbours’ gardens and crops served as free fodder to their roaming animals.

Patrick Brennan wasn’t the only bad apple is this respect, but, added to his other sins against his neighbours of both races, it made him public menace number one.

The Bishop put his finger on what was really a community problem when he suggested that potato patches be fenced. Note that the both he and the authorities laid the onus on landholders protecting their property from marauding livestock rather than placing the blame, and the solution, where it belonged, with cattle and hog owners who let their herds run wild.

Even Vancouver Island Expedition explorer Robert Brown, who was just passing through and had no stake in local affairs, crossed swords with Brennan. In his case he was able to get even, of sorts, by immortalizing the fiesty settler in his published report.

“...An Irishman has built and fenced in a farm on part of the Indian Reserve and carries things with a high hand. The best landing place is at his house and he refuses to [canoe] anyone across [the bay] except at high figures beyond reach of the settlers’ means.

“His pigs run out among the Indians potato patches and if they remonstrate they get nothing but abuse and ill usage and the other day he shot poor little Lemon’s (The Indian Boy) dog because he thought Lemon [Lemon’s father, surely—TW.] had killed one of his pigs. The ball passed between two [women].

“The men were much excited and begged of the priest to be allowed to kill him. The man ought certainly to be punished.

“The whole of the whites speak of him as the Black sheep in their midst and the Indians hate and despise the man.”

Quite a testimonial to Brennan’s character who seems to have owed his continued good health to the becalming counsel of Farther Rondeault.

Patrick had his own version of the affair, of course. In a letter to Victoria Police Magistrate Augustus Pemberton he complained that his cattle had been “maimed and injured”. Pemberton wasn’t too sympathetic, however, having heard so many times of “the general character that he bears in the country.

“He seems to be very violent and harsh in his treatment of the Indians. I think it desirable that he should be removed.”

Unfortunately, Brennan was able to flash a Surveyor-General’s statement, dated July 27, 1861, granting him a “legal claim to not less than 20 acres and improved by him at the entrance of the Cowichan River, on Indian reserve”. Read that again, carefully; he was deeded 20 acres even though it was situated “on Indian reserve”.

There appear to have been some resistance on the part of Indian Affairs, however, as in 1866 he was served with an eviction notice. The final result, alas, was that, in August, the Colonial Legislature confirmed his ownership. On Dec. 23, 1867, he obtained his certificate of ownership to 20 acres upon payment of $48.50. Another entry in the lands registry notes he got his Crown Grant on June 31 [sic], 1871.

The bottom line is he now owned the land legally, period. And we wonder why First Nations peoples believe they have been unjustly dispossessed of their lands?

Throughout all his difficulties with his neighbours, Brennan steadily prospered. Mind you, if local suspicions were correct, he was able to keep his overhead load by rustling some of his neighbours’ cattle from time to time although, for years, these allegations couldn’t be proved. To show how well he was doing, in just a few years, he was believed to be one of the Valley’s wealthiest farmers, with two oxen, two horses, 30 cows and eight pigs.

But, finally, he got caught altering brands on a calf owned by Fred Crate for which he was fined $25. He was luckier on a second charge of rustling, this one pressed by Francis Decede who accused him of “wrongfully branding cattle” from FD to PB; he got off with a tongue lashing from Justice Needham. Threatening Bill Chisholm with a gun earned him another fine and, in another neighbourly feud, he fired his revolver at James Morley.

For five tempestuous years his neighbours had hoped Brennan’s application for title to “not less than” 20 acres “on Indian reserve” would be denied. But, as we’ve seen, he was upheld and they were stuck with him.

Ironically, when Patrick did vacate the premises, not long afterwards, it wasn’t by his choice—he was taken away in handcuffs!

This was far more serious than rustling. After yet another of his run-ins with his neighbours, he and a former best friend Thomas Benjamin Shaw, who seems to have been as cantankerous as he was, had become sworn enemies.

Reminiscent of their Wild West days in gold rush California, when they ran into each other in Tom Bishop’s general store, it was no holds barred.

Harsh words led to Shaw calling Brennan a liar—a challenge to the death south of the 49th parallel.

Armed, just like in the good old days of the American frontier, Brennan went for his gun as Shaw headed for the door. Twice the gun misfired but a third shot penetrated Shaw’s coat although it didn’t wound him. A warrant was issued for his arrest and served by Provincial Police Constable Thomas Mitchell.

Based upon newspaper reports of the affair, the late Cecil Clark, then retired as deputy commissioner of the B.C. Police and the author of a series of true crime articles in the Colonist’s weekly Islander magazine, speculated the “revolver’ must have been a derringer as, according to Mitchell, the seized weapon had two barrels; one was empty, one was loaded.

At his trial before Judge Begbie, despite the testimony of witnesses (among them Father Rondeault) that Shaw had threatened to shoot him on sight, Begbie was having none of it. He instructed the jury to render a verdict of guilty of shooting with intent of murder or to do grievous bodily harm.

After half an hour’s deliberation the jury obliged by convicting Brennan of, in their words, “shooting with intent to do serious bodily harm” and recommended mercy.

The misnamed ‘Hanging’ Judge Begbie had no sympathy for Brennan. —The Canadian Encyclopedia

When his lawyer pleaded for a light sentence because of his wife and children and supposedly poor state of health, the irascible Begbie snapped that he should have thought of all that earlier. Begbie, who seems to have been unable to resist Biblical analogies, wasn’t done. In this case it was Balaam’s Ass: “Am I not thine ass: have I not always done thy bidding.”

Or, as Begbie translated it, “So might the pistol have thought. Am I not your pistol—have I not always done my best for you and am I not not now doing all I can [referring to the two misfires] to save your neck?”

“But, no! The devil then came to your aid and the pistol went off!”

In short, no sympathy from Begbie who, it appears, thought Brennan lucky, thanks solely to his gun’s malfunctioning, to have escaped killing Shaw for which he’d have faced a hangman’s noose. As it was, he sentenced him to two years with hard labour.

Patrick Brennan, un-lamented Cowichan Bay farmer, cattle rustler, would-be murderer and all-round bad neighbour, served his time in the Victoria gaol where, infirm or no, he likely contributed to repairing the city’s streets while serving on the chain gang.

There’s no record of his having returned to the Cowichan Valley and his house and acreage were bought by Swedish couple named Nelson then the Edward Marriner family.

160 years later, his contested acreage just eastward and across Tzouhalem Road from St. Ann’s Church cemetery, remains a cultural island, surrounded by, but alienated from, reserve lands.

Footnote: When Patrick Brennan made the news in September 1867 it wasn’t about his feuding or rustling but because he was exhibiting “a fabulously rich quartz sample” that Tom Shaw had found at the foot of Mount Tzouhalem”. Unfortunately, because it was a piece of float, no one knew its source.

Could there be, as a writer in the Colonist pondered long ago, be a potential mine on Mount Tzouhalem?

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.