Cowichan Lake Children Fought Cougar to Standstill

Tony Farrar, 8, and Doreen Ashburnham, 11. —Kaatza Museum photo.

We must go way back to Sept. 23, 1916. On that Saturday, Cowichan Lake’s Doreen Ashburnham and Anthony Farrer were walking along a forest trail on the South Shore, bridles in hand, to their pastured ponies.

They almost ran into the cougar, “lying quite still in the pathway”.

As they turned to flee, the animal pounced on Doreen, 11, from behind, knocking her to the ground. Eight-year-old Anthony, showing great courage, flailed at the cougar with his bridle, causing it to release Doreen and, rising on its hind feet, meet a combined attack with their fists.

“The hungry creature managed to knock the little fellow down on his side and began tearing his scalp with its claws,” the first newspaper account reported. “Filled with anxiety for Tony, [Doreen] jumped on the animal’s back, trying to drag his head back. Then she gouged at one of his eyes.”

The enraged cat continued to slash at Tony—until Doreen, in desperation, thrust her arm into its mouth.

Picture it: Doreen, all of 11 years old, is astride the cougar’s back, her arm clenched between its teeth as she yells for he companion to flee. Somehow she manages to free herself after looping her pony’s snaffle around the cat’s head, effectively muzzling it!

As the frantic animal tries to free itself she joins Tony in flight.

With his head start, a mauled and bleeding Tony made it home first and raised the alarm. Doreen’s father Lawrence and 17-year-old neighbour Charlie March had no difficulty in tracking, treeing and shooting the cat which measured almost eight feet long, but not before it slashed one of their dogs.

An examination determined that the cat was old, blind in one eye and hadn’t eaten for some time, weighing only 77 pounds. Numerous wounds on its underside showed the ferocity with which the children had whipped it with their bridles.

“The pluck of the children is most remarkable as they are both very timid by nature,” a newspaper reporter marvelled. Despite her own injuries—she’d carry the scars for life—Doreen’s sole concern was for Tony: “Don’t worry about me, take care of Tony,” she’d urged her parents.

To those who expressed their wonderment at her courage, she simply replied, “I had to save Tony because I was the oldest.”

Medical attention hadn’t been immediate. Mrs. Ashburham had had to leave first aid to their neighbours while she rowed across the lake to fetch Dr. R.N. Stokes, retired. Returning with her by the same means, he was able to make the children comfortable by the time Drs. Watson Dyke and Dr. Hall, and the head matron of King’s Daughters’ Hospital, arrived from Duncan.

For Tony, it was 36 stitches (it would take twice this many by the time he had surgeries to repair the wounds to his face and scalp) and a trip by car to the Duncan hospital. Her arm bitten through from shoving it int the cougar’s mouth, and other injuries to her hands and body, seem to have kept Doreen from the arduous drive into Duncan until four days later. Full recovery was the diagnosis for both if blood poisoning, a real threat in that pre-antibiotic age, didn’t set in.

Chief Justice Gordon Hunter of Shawnigan, who’d been staying at Cowichan Lake, publicly declared that he was going to nominate both children for the Albert Medal for Heroism.

Twelve days after the attack, Tony was still in hospital but making excellent progress. Doreen was by then an out-patient, coming to town only to have her dressings changed. Their mothers were said to be “most gratefully impressed with the conveniences and staff of the hospital.”

Tony’s return home came after their attacker, now stuffed, had been publicly displayed in Victoria and had earned $539.55 in ticket sales for the Red Cross.

Tony and Doreen pose with cougar pelt before it was stuffed and, presumably, mounted for display. —Kaatza Museum photo.

Five months after their horrifying adventure it was announced that His Majesty King George V had approved the awarding of the Albert Medal of the Second Class to Doreen and Tony whose case had been presented to London by the Royal Humane Society and ex-premier Sir Richard McBride. The youngest recipients of such an honour, they received their medals in a special presentation in Victoria by the Governor General.

The pair’s heroism brought them international attention. Former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt “congratulated British Columbia on having two such heroic youngsters,” and there was talk of their receiving the Carnegie medal. (“The Carnegie Hero Fund awards the Carnegie Medal to individuals in the United States and Canada who risk their lives to an extraordinary degree saving or attempting to save the lives of others.” Although both children displayed remarkable heroism, they did so to save themselves so, strictly speaking, they didn’t meet the criteria of the Carnegie Medal.)

Their celebrity came at a fearful cost: two weeks’ hospitalization and severe facial and scalp wounds requiring 72 stitches for Tony. Doreen, her right arm punctured through by the cougar’s teeth, bore the scars for the rest of her life.

They seem to have taken the emotional trauma and the resulting acclaim well. In California, where their mothers, girlhood chums as well as neighbours, had taken their families for the winter, they were interviewed by a San Diego newspaper. The reporter marvelled that Tony, who was still swathed in bandages months after the attack, spent much of the interview hunting “wild beasts” about the house with a cap gun. It’s from this source, not local news accounts, that we learn that Doreen was “pretty, blue-eyed and blonde,” and Tony was a “sturdy, chunky youngster whose eyes are firm and steady”.

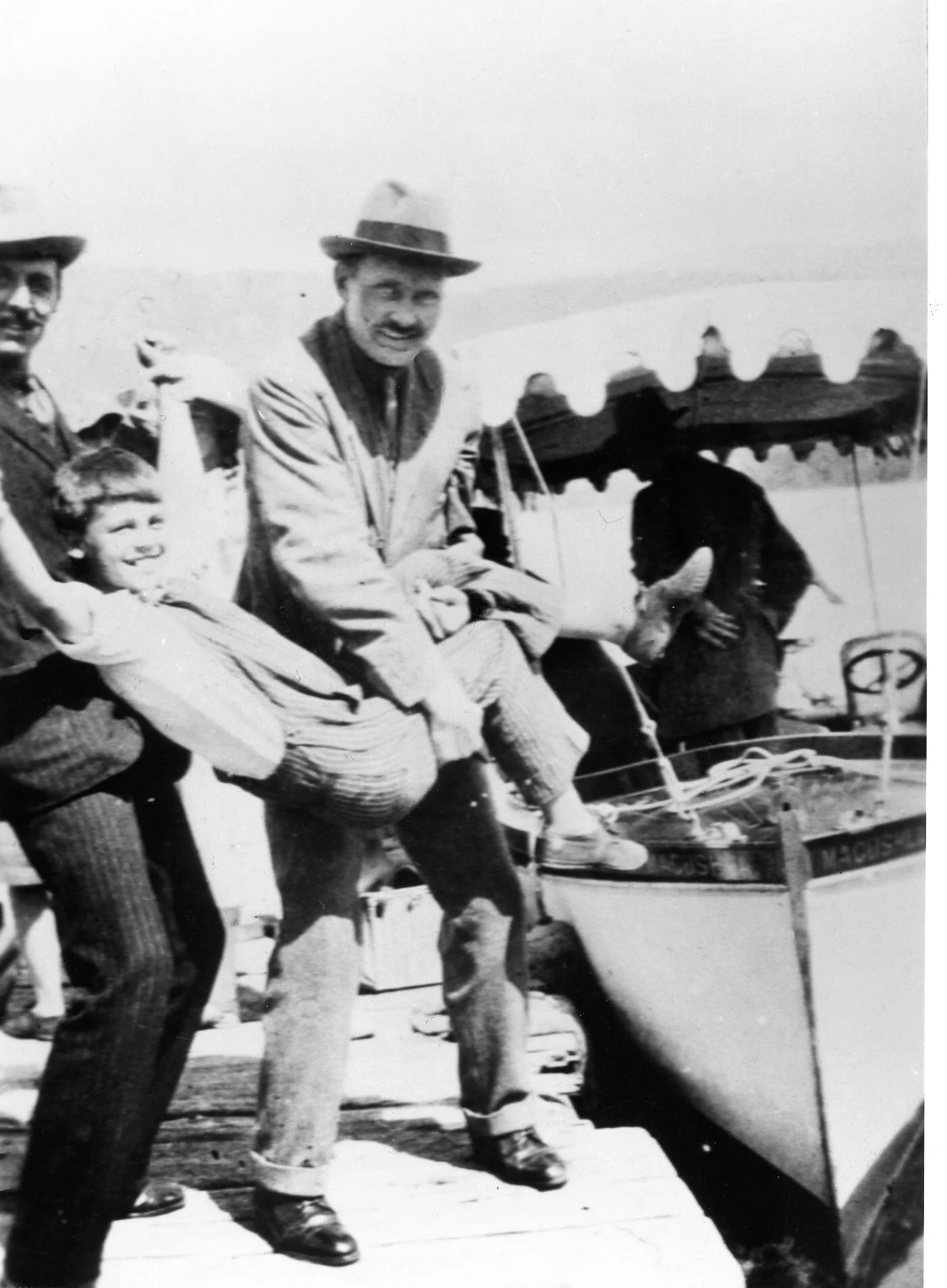

HRH Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, pretends to throw a recovered Tony off the Ashburnham’s dock. —Kaatza Museum photo.

Only his older sister Dot seems to have been nonplussed by it all. There’s a distinct note of envy in her expressed wish to “get into a fire or something or other that’s brave so that I can get a share of this”.

What ultimately became of these young heroes? It’s not often that newsmakers leave their recorded fates to posterity, their deeds usually being forgotten over passing years. Not so with Doreen and Tony. Fourteen years after his terrifying encounter with a cougar, Tony Farrar, by this time a 22-year-old army officer, again made newspaper headlines. A graduate of Brentwood College and well-known as an athlete, he’d served in the 16th Canadian Scottish Regiment before transferring to the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, Winnipeg.

A young Tony Farrar, seated second from right in front row, and classmates at Brentwood College. —Kaatza Museum photo.

At Manitoba’s Camp Borden, in July 1930, Lieut. J.L. Farrar’s life was ended on the firing range when he was struck in the head by a bullet during firing practice. It was a freak accident and an ironical ending for the former eight-year-old who’d helped to fight off a starving cougar with his fists.

An editorial in the Victoria Colonist praised his courage as a boy and as an athlete: “At rugby as a (wing) three-quarter he always made his way straight for the line, and was an intrepid tackler and never spared himself in any effort. ‘Tony’ Farrar was one of the type that makes excellent soldiers. His early training at Brentwood College, in the Canadian Scottish...equipped him with a character development that enhanced the admirable qualities he possessed. He has been cut off in the flower of his youth, but he has left memories to his generation of devotion, courage and sportsmanship that are well worthy of emulation.”

Young Lieut. Tony Farrar in uniform. —Kaatza Museum

Married less than a year, Tony was interred with full military honours in the Veterans’ Cemetery, Esquimalt. Hundreds attended his funeral at Esquimalt’s St. Paul’s Garrison Church.

In one respect, at least, fate had spared him. His scalp had been almost torn off by the cougar and, it must be presumed, restitched in place by doctors. To Doreen he’d confided a fear of eventually going bald and the ugly scars, no longer hidden, becoming apparent...

Upon her marriage Doreen Ashburham became Doreen Ruffner. In 1977 the San Pedro, Calif. resident visited friends at Maple Bay. Local journalist Ann Andersen described her as a “strong woman, almost overpowering but not quite, surrounded by an aura of experience and exuberance which threatened to overflow the sun-filled room where we talked”. Her face was lined but her vivacious manner, hand gestures and sparkling eyes” belied her 72 years.

Andersen was left marvelling by the youthful septuagenarian who’d experienced places and events of which you and I have only dreamed”.

An only child, Doreen’s early life in Essex, Eng., was one of privilege: imagine growing up in a 120-room mansion with 60 servants. (Mind you, it had just a single bathroom!) This modest homestead, a family hand-me-down, did her father, Lawrence Ashburnham, little good, however. As the fourth son he had to shift for himself, albeit with a handsome allowance, rather than enjoy outright inheritance which went to the eldest son.

It was because of Doreen’s fragile health, she later said, that the Ashburhams forsook the Old Country for, of all places, Cowichan Lake.

Life on the Canadian frontier wasn’t total hardship for them as Mr. Ashburnham commissioned the building of a 16-room house on their 500 acres. The lake “was a gorgeous place in those days. It was wild, it was rough, but it had a beauty we had never seen before. Of course, it was wrenching for my mother. She brought her maid and a nanny for me with her, but couldn’t even boil water when we arrived.

“There were no roads and we came down the lake on a boat. The train came once a week and there was one general store and post office combined” in Lake Cowichan.

Young Doreen’s health steadily improved, no doubt the result of conditioning.” I can’t count the number of times I had all my clothes taken off and was thrown into the cold water. That soon toughened me up.”

As she so ably demonstrated in September 1916 when she and eight-year-old Tony battled the cougar with nothing more than their ponies’ bridles and their fists. She proved the ferocity of the attack by rolling up a sleeve and showing some of her scars.

(Every other year she attended ceremonies in London for winners of the George Cross which had replaced the Albert Medal originally awarded to her and Tony.)

After recovering from the cougar attack Doreen remained at Cowichan Lake other than attending school in Victoria and spending winters in California with her family; in 1925 she was presented as a debutante to King George V. Later, after being taught how to play by Will Rogers, Doreen joined the first U.S. women’s polo team. Then she was off to Europe to compete internationally as a show-jumper before, at the age of 30, acquiring a pilot’s license. This, not long after Lindbergh flew the Atlantic. During the Second World War she was one of a group of civilian women who piloted military aircraft from the U.S. to Great Britain.

“About the only type of plane I haven’t flown is a jet,” she modestly claimed.

Not until 1962 did she marry a civilian professor with whom she had a daughter.

In another interview Doreen said she’d trained in wrestling, boxing and ju-jitsu—“More useful to me in my checkered career than you could possibly imagine”—“and had had her nose broken “about three times” while attending an exclusive private school in the U.S., her tuition gratis because of her heroism.

Although overweight in later life she claimed to have “muscles of iron” and invited her interviewer to feel them.

Altogether, quite an exciting life if she is to be believed. The late Duncan researcher Doris Benjamin, to whom the author is indebted for many of the details of the Ashburnham-Farrar-cougar saga, believed Doreen to have been “a real storyteller: She had much excitement at age 11, the rest of her life story had to have events and actions to compete with it.”

Others have openly challenged Doreen’s veracity, particularly in regard to her stories of her exploits in adulthood. But none deny her courage on that terrible day in 1916 when she and little Tony met a cougar on the trail and had to fight for their lives.

So Soon We Forget...

History is a funny thing. In July 2000, three-quarters of a century and half a world apart, the old and new made headlines in the same issue of a Victoria newspaper.

On Tofino’s Vargas island, it was reported that a 23-year-old university student was mauled by a wolf in one of the very few such incidents on record in B.C.

And in London, a George Cross medal for heroism won by a Cowichan Lake girl in an encounter with a cougar was to go on the auction block where it was expected to sell for $18,000.

The British Merchant Navy version of the Albert Medal For Lifesaving (www.naval-history.net/WW1MedalsBr-AM.htm).

The George Cross, the civilian version of the military’s Victoria Cross.

This was Doreen Ashburnham’s George Medal, of course, “the youngest recipient of a British gallantry award [sic]”. Tony Farrar, her younger friend and companion on that historic day, went unnamed in this account which was both inaccurate and unfair.

To explain: According to www.naval-history.net/WW2MedalsBr-GC.htm “The Albert Medal was abolished in 1949, being replaced by the George Cross, and the second class of Albert Medal (in bronze) was only awarded posthumously. In 1971, the Albert Medal was discontinued (along with the Edward Medal) and all living recipients were invited to exchange the award for the George Cross.”

Instituted by a Royal Warrant in 1866, the Albert medal originally was intended to recognize saving life at sea. A further Royal Warrant in 1867 created two classes of the Albert Medal, the first in gold and the second in bronze, both enamelled in blue.

By invitation in 1974, Doreen had exchanged her Albert Medal for a George Cross. Thus it is that Doreen Ashburnham is listed in the Register of the George Cross, which is “aimed at recognizing the valour of citizens and service personnel...for feats of the greatest heroism or of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme danger”.

The George Cross consists of a plain silver cross with a circular medallion in the centre, surrounded by the words ‘For Gallantry.’ The ribbon is dark blue.

Which explains why, in 2000, 84 years after her fateful encounter with a starving cougar, Doreen Ashburnham-Ruffner was honoured as the GC’s youngest recipient.

But not Tony Farrar. Because his family didn’t exchange his Albert Medal, he has no George Cross, the civilian equivalent of Britain’s and the Commonwealth’s highest military honour, the Victoria Cross. So, when her daughter placed Doreen’s famous GC on the auction block in July 2000, a brief news account failed to even mention Tony by name.

So goes history. For Doreen Ashburnham-Ruffer, formal recognition and, of all things, her own website.

For Lieut. Tony Farrar, three years her junior, every bit as brave and truly the Commonwealth’s youngest designated hero, a tragically short career as an army officer and a forgotten grave in Esquimalt’s postcard-perfect Veterans’ Cemetery.

Lieut. Anthony J.L. Farrar takes his final rest in ‘God’s Acre.’ Established in 1868, it’s one of only two cemeteries owned operated by Veterans Affairs Canada and is a designated National Historic Site. —Royal Canadian Signals Corps photo. (RCSigs.ca)

* * * * *

Fast forward to 2016,and an email from fellow member of the Cowichan Historical Society, Allison Irwin who’d just visited London, Eng. with husband Tony and their son. I’ll let Allison tell you about it herself:

“When [we] were away last month, our last major stop...in London was the Imperial War Museum. Once inside the building, the three of us headed off in different directions to see the exhibits. I made it up to the Lord Ashcroft Gallery on Level 5; that’s where you can read about people who have been awarded the Victoria Cross and the George Cross.

The Doreen Ashburnham exhibit with the eye-catching skull of a cougar. —Photo courtesy Alison Irwin

A close-up showing a picture of Doreen and both the Albert Medal and George Cross. —Photo courtesy Alison Irwin

“As I walked along the last row in the gallery, a skull mounted by one of the displays caught my eye! It was a cougar’s skull, and below it was a picture of a young girl, Doreen Ashburnham. Having worked at the Cowichan Valley Museum in town, I recognized the story and was thrilled to see an item with a connection so close to home.”

* * * * *

We’re not quite done. In February I received an email, care of the Cowichan Valley Citizen. ‘M’ wanted to know who holds the copyright to two photos which ran with one of my articles on this most famous of all cougar attacks. (They were used with permission of Kaatza Museum.)

“I am an Old Boy (1960-67) of St. Michael’s [University] School in Victoria,” ‘M’ explained. “Anthony Farrer [sic], the boy in the attack, went to St. Michael’s from 1919-23. The story was told to my class [60] years ago. For the last several years I have been volunteering in the archives at S. Michael’s. [A] cougar head was discovered in a box in a storage room a week ago, and I was asked what I knew about it.

“Quite a bit, actually. So now I am writing up this story for a school magazine.”

He and the school magazine editor thought it essential that the article be accompanied by archival photos hence his query to me about Tony Farrar’s adventure as a child.

M’s reply: “The bare bones of the cougar head discovery almost literally are bare bones. Last week, two employees of the school were cleaning out a storage room and, in a box underneath a bunch of papers, suddenly found the head glaring up at them. One of the employees is connected to the school archives and asked me if I knew anything about such an animal.

“By extreme coincidence, the story had been told to my class at St. Michael’s 60 years ago and I remembered it. During the course of my work in the archives a few years ago I came across a boy’s name and a reference to a cougar, and realized then that this was the boy of the story. When I was asked the question 10 days ago, the connection was right there...

“From that point in the current story, it was easy to google Anthony...to find out the details of the attack, its aftermath, and something about the rest of Doreen’s and Anthony’s lives...”

It’s intriguing to speculate as to the St. Michaels University School cougar head which had been so long stored away that it was forgotten. It’s not likely that it’s that of the cougar in the story which was stuffed and mounted, although what ultimately became of it I can’t say. Then there’s the skull in the Imperial War Museum.

Unfortunately, St. Michael’s magazine editor never did respond to my requests for a photo to accompany today’s Chronicle.

PS: If you’d like to see how big a full-grown cougar really is, close up, there’s a stuffed one on display in the B.C. Access Building, Duncan.

Say, you don’t suppose—?

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.