Cowichan’s ‘Hanging Tree’ (Part 1)

A grotesque memento of the American Wild West’s violent history of law and order, the ‘hanging tree’ of the appropriately named Vulture City, Arizona. —Wikipedia

With Truth and Reconciliation has come a new awareness of and sensitivity to our colonial history.

Everything about British Columbia’s formative years, once taken as gospel, is now under review.

Not all of this second-guessing has been objective; some of it is revisionist to the point of insult. Does any sensible person really believe that it was B.C. colonial policy to jack-boot its authority over the original inhabitants with fire and sword?

Some would argue, yes, because there were multiple occasions, well recorded in the press of the day and by the colonial and naval officials involved, when the Royal Navy administered “justice” with cannon fire by destroying First Nations villages.

These marine police expeditions sometimes resulted in death and injuries—what became known, cynically, as “collateral damage” in the Vietnam War.

Was this rule by terror? Or was it, as Vancouver Island then British Columbia colonial authorities believed, the only practicable way to impose law and order throughout a vast future province where Indigenous peoples, many of them armed and militant, outnumbered European settlers by the ten’s of thousand’s?

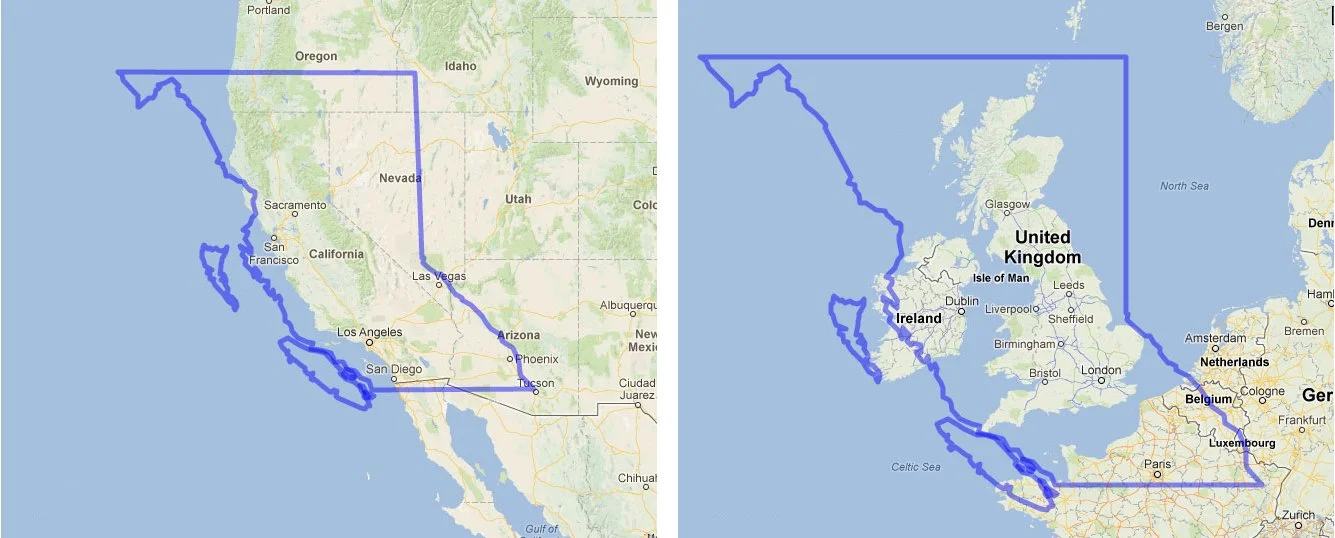

These maps show the comparative size of British Columbia. Technically 944,735 sq km, or 764,764 sq miles, it’s bigger than the United Kingdom and Ireland combined, and encompasses all of California and sections of Oregon and Nevada. This is the vast area over which the British colonial governments, first that of Vancouver Island then all of the B.C. mainland, tried to impose British authority and ‘justice’. —www.bcrobyn.com/2012/12/how-big-is-british-columbia/

Rightly or wrongly, it’s irreversible fact that Europeans (i.e. British) had arbitrarily staked a claim to all of what we know today as British Columbia. There was no turning back and many of the resulting problems remain with us today.

Chronicles readers can judge for themselves over the next several instalments how they think the governments of the day should have acted as they read the amazing saga of ‘Cowichan’s Hanging Tree.’

* l* * * *

There are two outstanding characters throughout this narrative, both of them the keys to the series of events recited. One of them is deservedly well remembered and is now regarded as an historical giant whose influence and mark still resonates in the 21st century as the province continues to grapple with First Nations land claims.

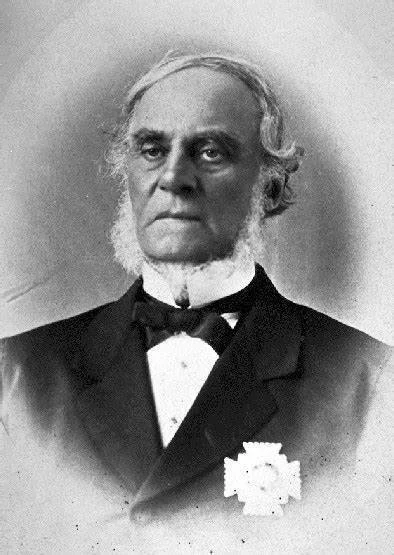

This is Hudson’s Bay Co. chief factor then colonial governor and, later, Sir James Douglas. To place him in historical context, here’s what the editors of the Encyclopaedia Britannica have to say about Douglas, “Canadian statesman”:

“Sir James Douglas, (born Aug. 15, 1803, Demerara, British Guiana—died Aug. 2, 1877, Victoria, B.C., Can.), Canadian statesman known as ‘the father of British Columbia.’ He became its first governor when it was a newly formed wilderness colony.

“Douglas joined the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821 and rose to become senior member of the board, in charge of operations west of the Rocky Mountains. After the establishment of the southwestern boundary with the United States, he moved the company’s headquarters from Oregon to Vancouver Island in 1849.

“As governor (1851–64) of Vancouver Island when gold was discovered on the Fraser River in 1858, he extended his authority to the mainland in order to preserve Britain’s foothold on the Pacific in the face of an influx of settlers from the United States. His action was approved by the British government, which then created the colony of British Columbia.

“Douglas became its governor in 1858 after severing his connection with the Hudson’s Bay Company. He was knighted in 1863 and retired in 1864.”

Fur trader, colonial governor and “statesman” Sir James Douglas. —www.biographi.ca

This is but an abbreviated outline of one of the most remarkable characters and careers in Canadian history!

It was James Douglas who was at the tiller of British colonial authority in the 1850’s and who ordered the punitive expeditions that ultimately culminated in Cowichan’s Hanging Tree.

* * * * *

Ironically, the other leading character is almost unknown to us now. In fact, I’ve described him in previous writings as B.C. history’s ‘invisible man’. So will-o-wisp was he that we’re not even sure which of more than half-a-dozen names by which he was known is correct.

But make no mistake:

To his employers, who needed his abilities and who begrudgingly tolerated, even blinded themselves to his frailties, and to the coastal First Nations who initially respected then feared and hated him, ‘One-armed’ Tomo Antoine was a man to be reckoned with.

For all that, more than a century and a half later, this Iroquois-Chinook voyageur, hunter, trapper, guide and interpreter is almost more phantom than fact. There’s no doubting that he played an essential role in Vancouver Island’s early explorations, that he was deeply involved in naval police keeping operations, and that he personally, if inadvertently, precipitated Cowichan’s single recorded hanging.

His employers, the Hudson’s Bay Co., rarely and barely mention him, can’t even agree on his name:

Was it Tomo/Toma/Thoma Antoine, Tomo Aumtony/Omtany, Thomas Anthony, Thomas William Anthony or Thomas Williams? After his fall from grace the company and Chief Factor (later Governor) James Douglas distanced themselves even further and, with passing years, Tomo Antoine (1823-1869) as he will be called throughout this narrative, slipped ever deeper into the murk of antiquity.

It’s known that his father, Toma Omtammy, was a French-Iroquois Metis who was employed by the HBC and who has been described as “a daring white-water canoe man and experienced voyageur”.

It was after his death in an ambush that Mrs. Omtammy, a member of the Columbia River Chinook tribe, gave birth to the future mystery man, Tomo Antoine.

Born neither white nor full-blood First Nation, he grew up in the chasm between the two castes, absorbing the best and worst of the fur trade and Indigenous cultures and early demonstrating his natural linguistic ability which would make him Chief Factor James Douglas’s go-to man for negotiating with the various tribes. (So good was he as an interpreter, even by his teens, that it’s said he could switch between English, French patois and several Native dialects without a blink.)

He was also smart, shrewd, fearless and totally at home in the outdoors with just a musket, knife and blanket.

These were his good points; his negatives were an extremely violent temper, his distrust of almost everyone but Douglas, and, increasingly over the years, a preference for lying and his fondness for rotgut liquor which invariably fuelled his anger.

Interestingly, it’s to HBCo. outsiders that posterity is indebted for knowing anything at all personal about him.

Capt. T. Sherlock Gooch estimated that he was about 45 years old in 1857, and a full-blooded Iroquois “of lower Canada,” of slight, wiry build, his copper-coloured face “lit up by keen, intelligent eyes” who spoke “the French dialect of that province well, and also English, and many Indian languages”. In short: “A valuable addition to any pioneering expedition in North America”.

Nanaimo mayor and coal mine manager Mark Bate remembered him as being a very handy man despite the loss of his right arm—”It was surprising with what celerity and power he could swing an axe”—and capable of conversing with most Island tribes in the Chinook trade jargon or their own tongues.

Roman Catholic Bishop Modeste Demers, who employed his linguistic abilities, wrote that “the Iroquois named Thoma, a devout young man, assisted by interpreting sermons and teaching [the Cowichans] hymns and prayers in their own tongue”.

Bishop Modeste Demers praised Tomo’s linguistic skills. —Wikipedia

Another who came to admire Tomo as a guide, interpreter and woodsman was Robert Brown, leader of the publicly sponsored Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition.

Tomo had shown up seeking work at Brown’s temporary office in the John Bull Inn, Cowichan Bay; he came in obvious penury but with glowing references. “He was at one [time] high in favour with Governor Douglas whose constant factotum he was on every expedition.” However, despite Tomo’s “unrivalled” abilities as a guide, hunter and interpreter, Brown had been reluctant to engage him because his notorious reputation had come to overshadow his acknowledged attributes.

Brown has left us one of the best descriptions of this historical phantom he referred to as Toma, noting (contrary to some other accounts) that he “spoke English without an accent, besides understanding nearly every Indian language on the Island...”

“He stood five feet odd in his ragged trousers and woollen shirt, a grey cap was set jauntily on his head, and a pair of wooden-soled boots, made by himself, were on his feet.

“More than that he had not. He borrowed a blanket from his friend the chief, and we supplied him with a rifle; so he declares with a big oath, as he squints along the barrel, that ‘he is a man once more,’ and in two minutes he is asleep under a tree, with the gun between his legs.”

In his report, and again in his memoir of the historic exploration expedition, Brown recorded much of the Native lore that he’d learned from ‘Toma’. Because hire him he did, and but for a single, memorable lapse—while in a drunken rage it took the combined strength of the entire company to subdue him—Tomo did all that was asked of him and more.

A fine hunter, he kept the expedition fed with wild game, interpreted the various tribal dialects and kept the party’s outnumbering Indigenous hosts in a state of respectful awe through his personal strength of character that, for all his diminutive size, bordered on intimidating.

One of Tomo’s most invaluable skills as yet unmentioned was his service to Douglas, whom he venerated like no other man, as a scout and spy among the Island tribes. The moccasin telegraph had never known the need for self-imposed censorship or restraint. Indigenous people talked openly without fear of recrimination and most of it, it seems, reached Tomo’s ears and, in due course, Douglas’s office.

Such was the extraordinary man known as Tomo Antoine, the gifted but flawed semi-phantom who would provoke the tragedy of Cowichan’s ‘Hanging Tree.’.

(To be continued)