Deja vu All Over Again – Chinese Spy Balloons Recall Japanese Aerial Bombardment of B.C. Forests

It’s uncanny how history mimics if not actually repeats itself.

Last month’s excitement over a series of so-called ‘scientific’ research balloons from China provided an eerie reminder of the Second World War. That’s when the Japanese attempted to ignite our forests with incendiary bombs delivered via the air currents of the aptly-named Japanese current.

Thousands were launched and many of them made it to the Pacific West Coast, from Oregon north through B.C., even as far east as Kansas. They caused the death of a picnicking family but, amazingly, as it may seem to us today, little in the way of the intended forest fires.

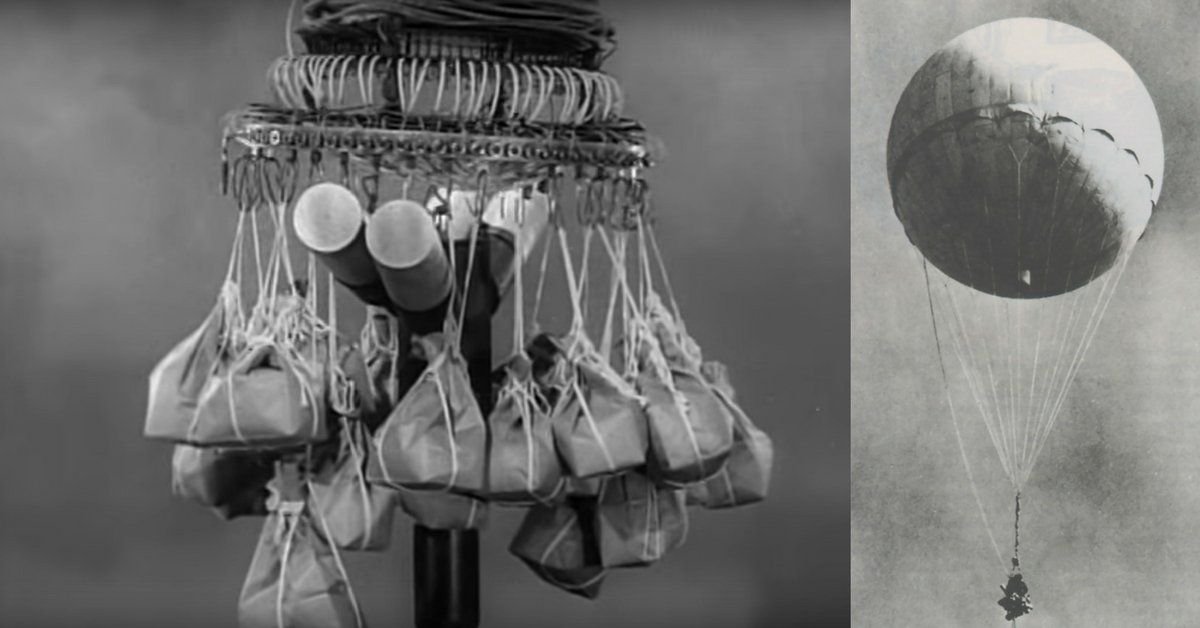

A sketch of the components of a fire balloon bomb. —utahhumanties

It was one of the best kept secrets of the Second World War.

That’s when Canada came under direct attack by the Japanese—not once, but hundreds of times. Possibly as many as 15 of those attacks involved the Cowichan Valley.

The Estevan Point lighthouse was subjected to a brief bombardment by the Japanese submarine I-26 on June 20, 1942. It has become folklore that the attack was staged by a ‘friendly’ naval vessel, likely American, to stir British Columbians to greater patriotic efforts. —www.ucte-ucet.ca

Although it’s generally accepted that Japan’s sole military strike against a B.C. target was the shelling by a submarine of the Estevan Point lighthouse on the west coast of Vancouver island in 1942, this isn’t the case.

An aerial assault on B.C.’s forests was conducted from late 1944 through early 1945.

* * * * *

The Japanese had first considered the possibility of using balloon bombs to attack the continental U.S. in 1933. But it was the momentous April 1942 Doolittle bombing raid of Tokyo that provoked the 9th Military Technical Research Institute to revive the idea of balloon bombs launched from submarines.

When greater priorities for the submarine fleet forced a change of plan, the idea of launching the balloons bombs, known as fusen bakuden, in the Pacific jet stream was initiated. Experiments by engineers and meteorologists throughout the winter of 1943-44 confirmed that balloons carrying four incendiaries and a 30-pound high-explosive bomb, could reach the American coast in 60 hours.

Hence the order from high command for the production of 10,000 bombs, their paper skins made from the bark of the Kozo tree fabricated by schoolgirls.

* * * * *

Not until October 1945, two months after Japan’s surrender, did official secrecy begin to lift and Valley residents begin to learn of their repeated near-calls with airborne incendiaries. At that time, Allied intelligence officers sifting through captured Japanese documents estimated that 9000 (actually 9300) hydrogen balloon-propelled bombs had been launched from Japan and carried at an altitude of 25,000 feet by the jet stream to land amid west coast Canadian and American forests.

Fortunately, most of the bombs that reached the B.C. coast failed to ignite or simply burned themselves out. But that’s not the reason that the Japanese finally abandoned the effort. It was because they had no way of confirming, local and national press coverage having been forbidden, the results of their bombing campaign.

For all they knew, for all the good it was doing their war effort, they were launching their bombs into outer space.

One bomb did claim the lives of a woman and five children enjoying a Sunday School picnic when they innocently examined a bomb which had landed nearby. Mrs, Mitchell was five months pregnant. They have the sad honour of being “the only Americans to be killed by enemy action during World War II in the continental USA.”

So far as is known, none of the thousands of other balloon bombs caused serious injury or damage.

By today’s standards everything about the Japanese fire bombs seems quite primitive—but they were deadly all the same. —www.pinterst.com

When some of the un-detonated bombs were examined, the U.S. Army apprised Canadian officials of what we, too, had to contend with. Because of the clampdown on secrecy, however, American and Canadian civilians were left completely unaware of what was happening.

Among the few who were in the know in B.C. were the Pacific Coast Militia Rangers, the unit best equipped for the job, the civilian Aircraft Det3ection Corps, forestry officials and police. Both the PCMR and ADC were assigned regional zones and men and women posted on lookout.

Alerted RCAF pilots shot some down after being advised to do so in a way that the device could be recovered for study. They did this by using their aircraft’s slipstream to steer the bomb in the desired direction before shooting away the balloon.

Civilians who reported discovering an exploded balloon were sworn to secrecy with the result that, “So well was this secrecy order observed by all those concerned that the Japanese failed to obtain the information [results] they so eagerly sought.”

As a result, the balloon bombing campaign was abandoned on April 1, 1945, just four months before the war’s end.

In March 1944, a balloon bomb “obligingly” failed to explode upon alighting in a snow field near Nanaimo Lakes and a trapper wisely didn’t tamper with its 26-pound explosive payload before informing the police. Disarmed, it was rushed to Vancouver for examination and for use as a demonstration model.

Its recovery, when made known to those in on the secret, sparked a flood of reports to Pacific Command of other “robot” balloon devices which, until then it seems, had been dismissed as harmless curiosities or, perhaps, downed weather balloons.

The Cowichan Valley, obviously, was on the balloon bombs’ flight path as there were numerous reports of their having landed or passed overhead, beginning with that of Mrs. R.C. Mainguy and Ranger D. Chaster and J. Cain who spotted one, March 28th, drifting north over Richard’s Trail in North Cowichan’s Westholme area at 6 p.m.”

Five weeks later, there was a 6 a.m. balloon report from unidentified parties at Deerholme, southwest of Duncan.

Reports of balloon bombs became more frequent:

May 28—Another 6 p.m. event.

June 13—A balloon is seen drifting from the Nanaimo area towards Salt Spring Island in the early evening.

June 14—Employees of Lake Logging Co. spot a balloon at high altitude southwest of Honeymoon Bay.

June 14—A second sighting at noon of the same day, also made by loggers, this one of a balloon (the same one?) over Hill 60.

June 15—Another doubleheader: Mr. and Mrs. George Potts, Duncan, report a balloon high over Cowichan Bay at 6 a.m., and CNR employees sight a balloon at Mile 48 in the Shawnigan Lake area.

June 18—Another sighting over Cowichan Bay.

June 25—This reported balloon isn’t actually seen but is suspected to be such, based upon a loud explosion over Heather Mountain. There’s no mention of a fire as a result.

July 9—John Dick “and others” report seeing a balloon dropping towards Somenos Lake. When search parties fail to find it, it’s surmised that it was carried on over the Quamichan area then over the saltchuck.

July 19—Yet another balloon is seen in the Quamichan area, this one drifting towards Salt Spring Island.

August 31—The last report is that of a balloon over Rounds logging camp in the Gordon River area, headed towards Lake Cowichan.

Several false alarms were attributed to sightings of the planet Venus which is highly visible in summer months. There also were reports of explosions occurring in the daytime and at night; most of them were attributed to blasting operations and one to a boy experimenting with a home-made mortar, but several remained unexplained.

Again, no fires were reported.

During the emergency, PCM Rangers investigated several spot fires without ascertaining their causes, conducted regular fire patrols in forested areas and prepared trails to assist firefighters should they be called into action.

The public were cautioned that the danger remained as it was highly likely that there were un-exploded balloon bombs in the woods; they were advised not to handle them but to report them to the authorities.

Although a failure, Japan’s balloon bombs campaign goes down in history as “the longest ranged attack ever conducted in the history of warfare” up until that time.

* * * * *

Friend Jennifer tells me that she’s convinced that she and her ex-husband found the remains of a balloon bomb on the Chemainus River side of Mount Sicker while bottle digging in the 1960’s. By then just the basket remained; likely the explosives had become detached when the balloon hit the trees or ground as, perhaps happily, they weren’t evident.

Several years ago, Roy Carver emailed me to say that he believed “all if not most light[house] keepers on the B.C. coast knew of the Japanese fire bombs during the 1944-45 war years.

“I remember seeing two fire bombs pass over near the light station as a small boy on Kain Island Light Station where my father was the station keeper. I think our wet climate helped a lot in not allowing the bombs to do their jobs.”

* * * * *

A collapsed Japanese fire balloon that landed near Bigelow, Kansas, Feb. 23, 1945. —Wikipedia Commons

Perhaps the final B.C. footnote to the balloon fire bombs occurred as recently as October 2014 when two forestry workers found one, half-buried in the Monashee Mountains near Lumby, B.C.

“They confirmed without a doubt that it was a Japanese balloon bomb,” said RCMP Cpl. Henry Price. “This thing has been in the dirt for 70 years.”

Seventy years or no, no one was taking any chances; the area was cordoned off and a Maritime Forces Pacific bomb-disposal squad dispatched to the scene. The explosive payload was said to be large, with a half-metre of metal casing buried in the soil and 15 to 20 centimetres showing above-ground.

The original explosive cargo would have consisted of two larger bombs and four smaller ones, designed to detonate on impact.

“It would have been far too dangerous to move it,” said Price. “They blew it to smithereens.”

* * * * *

In his book Deadly Allies: Canada’s Secret War, John Bryden reveals that the Canadian and American governments had initially had greater concerns than the fire bombing of forests—the very real and deadly possibility that the balloons were intended as weapons of biological warfare.

Without explanation, west coast civil and military officials were alerted to watch for any outbreaks of “unusual diseases”. In both countries the recovered balloons were frozen until they could be examined not just for their explosive cargoes but by the Surgeon General’s office for evidence of virulent microbes in the sand or water used as ballast.

Coincidentally, this enabled the U.S. military to identify the balloons’ launching pads—American merchant ships having participated in a pre-war program to retain samples of the sea bottom for study whenever they anchored in a Japanese port!

There’s a disturbing sidebar to the balloons’ potential use as biological weapons, author Bryden relates. The Canadian government prepared to respond in kind. A bomber loaded with several tons of ground peat was kept on 24-hour standby at Ottawa’s Uplands Airport, ready at a moment’s notice to take off for Vancouver, Hawaii then Japan.

Just before takeoff, the peat would have been infected with a deadly virus.

* * * * *

After causing excitement for weeks, the recent spate of high-flying balloons with their suspected high-tech spyware ended in a whimper when several of these reported visitors were shot down over Alaska and northern Canada.

The last news report was headlined, “No indication downed objects [sic] were operated by foreign state, MPs told.” This, after U.S. officials had declared that the first balloons ordered destroyed by President Biden were definitely high-altitude spyware launched (admittedly) by China.