Diary of Death

“Been out of food for two months. For God's sake pick us up."

Whenever tragedy struck the west coast of Vancouver Island during the years immediately preceding the Second World War, it usually was a Ginger Coote Airways plane to the rescue. Sometimes, however, even its dauntless pilots couldn't help.

So it was for Vancouver trappers James H. Ryckman, 56, and Lloyd Coombs.

Zeballos in 1937. When trappers Ryckman and Coombs realized they were in trouble, the frenzied gold rush had peaked and air traffic had dropped off substantially. —BC Archives

The key to their tragedy apparently lay in Ryckman's confidence that he and his young partner would have no difficulty in flagging down a passing plane from their Vernon Lake cabin at the close of the trapping season. But, by 1939-40, the height of the Zeballos gold rush, when planes crowded the skies, had passed; it was too late for the trappers.

Rescuers found their remains and a grim account of their final days in a diary kept by Coombs. On a large piece of fungus, dated Jan. 30 1940, he’d branded: “We're both too weak to hike a mile a day. Can't do nothing but stay here until a plane comes in."

By the time they’d realized that no planes would pass overhead they were too weak to hike out. Then Coombs’ journal had become a diary of death as starvation stalked both men.

For the first weeks the entries recorded the daily chores of checking traps and fishing and heavy winter rains. By mid-December, a note of desperation was becoming apparent, as fishing was mostly unsuccessful and supplies were running low.

On December 17th, Coombs mentioned for the first time what was to become a desperate ritual: "Jim fished and watched for a plane.”

Ginger Coote; his company, Ginger Coote Airways, would merge with several others and become Canadian Pacific Airlines. Coote’s pilots had served as an airborne lifeline during the Zeballos gold rush until business slacked off. —BC Archives

Breakfast, December 18th, consisted of one-half a pancake each with fish for lunch and supper. The next day, they ate a raccoon caught in the traps and four trout. December 20th, they finished the last of their flour, three trout and a squirrel. In following days they survived on trout, squirrels and another raccoon. Christmas dinner was roasted ‘coon and a can of corn.

"We didn't have a turkey dinner but just the same we're not hungry, so we have that to be thankful for."

The weeks passed, the weather continuing to deteriorate, the partners existing on an occasional trout and any animals caught in the traps—“no plane yet.” By the end of February, both were almost bedridden, apparently from illness as well as malnutrition. February 26th, Ryckman captured 19 wild canaries, a trout, a marten—“and a darn nice A-1 fur too"—a squirrel, and collected bark.

February 26th, the bill of fare was “tea for breakfast, tea for dinner and tea for supper”.

Then Ryckman assumed writing the diary, Coombs being too weak, until March 10th, when the latter again resumed making the entries: “Jim too tired to write." A week later, Coombs wrote his last entry, addressing it to his mother:

“Jim died today at 2:00 p.m. This might be the last I’ll have the nerve to write, so if I do anything wrong please forgive me. I can't stick it out any longer. The Bible is packed in the bottom of my pack and I haven't the strength to get it out so I can't even say a decent prayer for poor old Jim.”

Then, in their haunted cabin beside Vernon Lake, Lloyd Coombs turned his rifle on himself.

When pilot Jim Haines finally checked on the overdue pair, it wasn't because he’d seen their pathetic distress signals, two white bed sheets erected on poles, or the SOS scrolled in red chalk on their little jetty: “South end of lake fishing. Been out of food for two months. For God's sake pick us up."

Provincial Police Constable and NJ. Winegarden, Corner Ralph Thistle and newsmen found the trappers in their bunks. Of the 1500 pounds of grub they’d taken in, not a scrap remained. The flour sacks had been beaten to “yield the last particle of flour and containers of sugar, rice, peanut butter and other foods had been cleaned out of the last crumb.

"Even the rotted carcass of a duck, discarded before Christmas, had been retrieved two months after. The only item of food left was a tiny quantity of tea in a jar.”

* * * * *

In August 2009, RCMP officers rescued a 77-year-old prospector who was reported missing near Eastlake in northern B.C. Former hockey player Ernie (Punch) McLean had been lost four days after falling 33 metres into a ravine while surveying a property for a gold claim near Dease Lake, 300 km east of Juneau, AL.

Disoriented, he climbed up the opposite side of the ravine then began going in circles. As was reported, he “had no photo, no GPS system, no emergency kit”. The survivor of a plane crash, several automobile accidents and being run over by a bulldozer later admitted, “It was a dumb move.”

But he kept cool, sure he could find his way out, that it was just a matter of time before he was found. As proved to be the case, unlike two American prospectors who vanished despite the incredible efforts of two provincial police officers who braved every obstacle for an incredible 800 miles in search of them.

Their incredible story appeared in the Nanaimo Free Press in August 1926.

“On patrol, 193-” is all the caption tells us of these B.C. Provincial Police officers. They not only risked their lives in the line of duty but often experienced real hardship—all for 30-odd dollars a month. —BC Archives

I’ve chosen to leave it in the words of the unknown Nanaimo reporter whose reportorial style, although stilted by today's standards, adds to the immediateness of the story as it was published 98 years ago. (I point out that ‘Indian’ was the accepted term for First Nation or Indigenous people in 1926.)

“Constable C.D. of Muirhead, of the Provincial Police post at Prince George, was in charge of the patrol. His sole companion for the greater part of the arduous Journey was Const. Fenton of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The patrol set out from Prince George on May 18th and broke trail 400 miles into the [wilds] of the Canadian Cassiar district, reaching their base on return on July 28th.

In that time the two men faced untold hardships, being forced to shoot their pack animals and trudge through deep snow in a land where few white men have trod.

Recovering bodies was all in a day’s work for a provincial police officer. —BC Archives

They built rafts and shot rapids over the swollen streams dividing the terrain into innumerable inland islands, and continued on and on until the quest was done. Once, their food ran out and for hours together they trod forward through the snow with pangs of hunger adding to their hardships... At the very outset of the hazardous journey Const. Muirhead sprained his ankle. His companion, with the aid of Indians, carried him to shelter, but next day he proceeded through though the sprained member was swollen and progress forward was only possible with a stick.

Prospectors Lost

The patrol, searching for traces of McClare and Saunders, two United States prospectors who failed to return from a whole year in the wilds of the Northlands, beat a wide trail through the country, following a cross-country beat that connected up the scattered outposts of civilization on the backwoods frontier.

From Prince George they passed in turn through Finlay Forks, Fort Grahame, Wrede Creek, Sustut Lake, Thutade Lake, Tatlatui Lake to Brothers Lake, where they came on the end of their trail. For weary miles they stumbled over the snow, forcing the pack animals, until Indian guides, discouraged, cut the animals adrift in the night.

The officers shot the remaining packhorses left to them and continued on foot with what little food they had left.

Trace Slender Clues

At the second 100 miles of their journey they unearthed the trail of an Indian, one Lewis Peterson, who was supposed to have seen McClare and Saunders in the summer of 1923, at the outset of their ill-fated journey. After a long side trip into the wilds the officers found Lewis Peterson, only to discover it was not the missing men he had seen but two other trappers who have since returned.

Resuming the main trail, the patrol pushed its way. At Thutade Lake, 350 miles from their starting point, they picked up a trail of a Bear Lake Indian, Lewis McClean. From the Indian whom they traced and found, the police uncovered the fact that yet other Indians had seen McClair and Saunders and had worked for them in the summer and fall of 1923.

This information led the patrol to the western slope of Brothers Lake where they found McClair's cabin and where undoubtedly the two men had spent the winter.

Traces of a raft at the edge of swollen rapids and signs of camp fires in a country where none but Indians have been for years, with the exception of the two missing men, continued the story. At Brothers Lake, the officers came on Peter Himadam, a Cassiar Indian, who had sighted the McClair-Saunders pack train about a year after the two men had entered the woods.

A BC Provincial police officer on his rounds “in the north” in the 1930s. —BC Archives

Traces were not wanting that the pack animals had been shot and the men had wintered in the cabin on Brothers Lake. At that point, however, all trace of the two white men vanished.

With their food running perilously low and the snow growing deeper as they progressed, the officers made a careful note of all they had discovered and started the return trip. Again they had to ford swollen streams, shoot rapids on improvised rafts and cut their way through the bush on the 400-mile return journey, most of it across un-trodden country.

So ended the routine summer patrol of the B.C. Provincial Police at Prince George, undertaken as a simple matter of duty and carried out with fearless courage in the face of untold hardships”. (—Nanaimo Free Press, Aug. 12, 1926.)

Note that this incredible feat was described as “the routine summer patrol” for BCCP officers stationed in northern B.C.!

* * * * *

There’s another great story of ordeal during the Cariboo gold rush in my files, one that I wrote about back in 1999.

Englishman John Helstone, John R. Wright, and Canadians William, Thomas and Gilbert Rennie, struck out for distant Cariboo on May 15th.The first half of their journey had been by railway, riverboat and stagecoach; the rest of the way to the Fraser River they’d have to hike through the Rockies to the abandoned Hudson’s Bay Co. post at Tete Jaune Cache.

Arriving there on October 4th, they encountered some snow “but the weather was very fine and black flies caused great annoyance," one of the Rennie brothers wrote. It was so mild, in fact, that some of their precious dried meat spoiled. Eleven days were spent building a canoe to navigate the Fraser.

With just enough supplies to see them to Fort (Prince) George, they experienced their first delay, a three-day portage, then made fairly good time until October 29th, when, about 100 miles above Fort George, they struck a sunken rock.

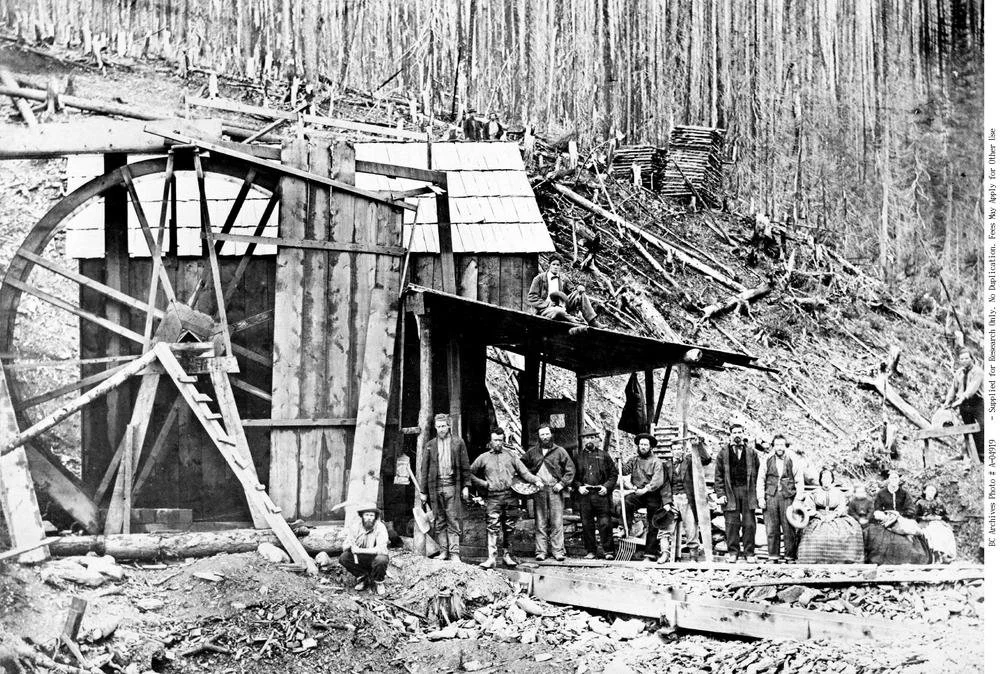

Stouts Gulch, 1868. The four adventurers of our story never made it to Cariboo. —BC Archives

“On both sides of the canoe was a boiling rapid rendering it impossible to reach the bank,” reported the Victoria Colonist. "Every effort was made to get...off but without success, and they remained there for three days and two nights during heavy falls of snow with nothing but dried meat to eat.”

Sixty hours of below-freezing temperatures on their bobbing Island for Gilbert and Thomas Rennie. The others fared considered considerably worse, having failed in an attempt to reach shore. On the second day of their stranding, Helstone and Rennie were rescued, but Wright was swept a mile and a-half downstream before he managed to land and hike back to his marooned comrades.

By means of a rope braided from strips of moose skin, all made it to shore, although the stranding had cost them most of their equipment and provisions. The adventures who’d so eagerly set out from Ontario five months before faced miles of deadly rapids before they reached Fort George.

Only by igniting gunpowder in a dry handkerchief were they able to make a fire, dry out, cook a meal and erect a shelter. It then took them days to build, with frost-bitten hands, a bridge of rocks and debris to reach their stranded canoe.

That night, they agreed that William and Gilbert Rennie “should proceed to Fort George which they thought was not more than five days’ journey there and back”.

They were unduly optimistic; instead of a five-day round trip, the race for help would take them all of 28 days. When they finally staggered out of the bush, across the river from the fort, they hadn’t eaten for 15 days and William had to be lifted into the canoe.

A relief party that finally reached the camp of Helstone, Wright and Thomas Rennie was appalled by the sight that created them: "The poor men had been reduced by starvation and cold to the last extremities and had actually killed and eaten one another."

Ironically, the last survivor was killed by passing Natives when he violently repelled their attempt at rescue.