Did a Sea Monster Guard the S.S. Islander's Gold?

As a kid I thrived on shipwrecks--in magazines and books, anyway. Photos in National Geographic and travel magazines of rusted hulks on semi-tropical beaches, underwater scenes of Spanish treasure galleons, and of Second World War naval ships on the sea bottom in the southern Pacific really turned me on.

By junior high school I was into reading the salvage epics of Capt. Harry Ellsberg and others then, years later, watching on TV the underwater explorations of Capt. Jacques Cousteau and the incredible deep, deep dives on the Titanic by Dr. Robert Ballard.

Long before then I'd made the wondrous discovery that British Columbia had its own shipwrecks--1000s of them!

In fact, a stretch of the west coast of Vancouver Island was known as the 'Graveyard of the Pacific' and for 'a wreck for every mile'.

I set out to catalogue them; a pursuit I finally gave up as being too big, too time consuming and, arguably, to no real purpose. But I did begin to write about them--perhaps several 100 by now, in newspaper and magazine articles and two books.

I came to joke that I'd sunk more ships than Nelson--in print!

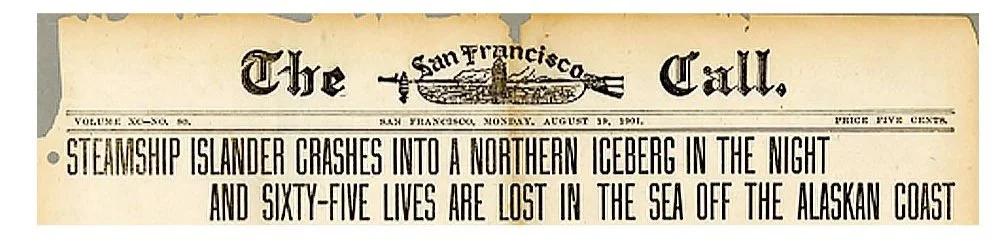

Fortunately for those aboard the sunken liner, the San Francisco Call's report of 65 lives lost was on the high side. --Alaska State Library

Early in that pursuit I'd read of the sinking of a coastal passenger liner, the S.S. Islander, after she struck an iceberg in Alaska's Lynn Canal during the Klondike gold rush. Little did I realize that the day would come when I'd have a direct connection to this historic tragedy.

That day is now and every day; the property on which I have my home, on Koksilah Ridge just south of Duncan, was subdivided from the large Keating estate. Andrew Keating Sr. and his two sons went down with the Islander.

There are three fascinating elements to the story of the Islander: her sinking with great loss of life, the subsequent attempts to salvage her reputed fortune in gold, and Mr. Keating.

Worthy of a 'sidebar' of his own, he was incredibly rich--t'was said that he once owned much of downtown Los Angeles--and he built a mansion (my neighbour) at 'Koksilah' which, long run-down, has since been restored and is itself something of a mystery.

* * * * *

The Victoria-based coastal passenger liner, S.S. Islander.

One of the more startling aspects of this maritime disaster is the speed with which the Islander, rated as a "fast, commodious and handsome craft," sank with the loss of 42 lives. It's a matter of record that she foundered within 17 minutes of striking an iceberg in Lynn Canal, the fjord-like approach to Skagway.

The tragedy began with the southbound flagship of the Canadian Pacific Navigation Co. racing through the canal' fog-shrouded narrows, early on the morning of Aug. 15, 1901.

Despite the limited visibility Capt. Hamilton Foote wasn't on the bridge--he was in the luxurious main saloon, presiding over a merry group of miners who, with their pokes, money belts and baggage packed with gold nuggets and dust, were celebrating their returning from the Klondike.

The officer actually in command during those final minutes was the Islander's pilot, Capt. Edmond LeBlanc who, equipped with night glasses, was on the bridge.

Again and again he squinted into the darkness, trying to see beyond the steamer's rapier-like bow. Despite Lynn Canal's notoriety for floating ice and the poor visibility, he made no attempt to reduce speed as the good ship S.S. Islander raced to her destruction in blissful ignorance.

At the helm was a third captain, Capt. George Ferry who'd boarded as a passenger and had assumed the role of quartermaster as a personal favour to Capt. Foote. But for an occasional correction of course, when the ship answered smartly to his caress, Capt. Ferry found himself with little to do other than to daydream and wait to be relieved of his watch as, up forward, LeBlanc continued his vigil. When, momentarily, the mist parted off the starboard bow and LeBlanc caught a glimpse of a small iceberg through his glasses, he made sure that it was well out of harm's way before returning to an 180-degree sweep of the canal with his glasses.

And so it went, as the Islander, both screws churning through the night at full speed, proceeded towards Victoria. A 10-year veteran of the Alaskan run, she'd navigated Lynn Canal many times without difficulty and had earned a reputation for speed, reliability and comfort.

Capt. LeBlanc was the first to realize that Islander's luck had run out when he suddenly spotted the iceberg, towering directly overhead. Even as he shouted the order to alter course and reduce speed he knew that it was too late, the ship continuing to charge its floating nemesis with almost suicidal glee.

Seconds later, with a heartrending crash and tearing of steel, she shuddered to a stop, her bow ripped wide by the rock-hard ice.

Immediately upon impact, the ship's spinning helm was torn from Capt. Ferry's grip. As he fought to regain control he instinctively forced the wheel towards the nearest shore in the hope that the Islander retained enough headway to drive her onto the beach. But she'd been ruptured by the force of the collision and the water rushed into her wounds with overwhelming speed.

Within seconds, the ship was down by the head and sinking rapidly. When her screws rose out of the water she lost her last chance of manoeuvrability.

Just as Capt. Foote, his face an ashen mask of disbelief, reached Ferry's side, a deckhand rushed into the wheelhouse to ask whether the crew should lower the boats. But Foote, unaware or unwilling to believe that his ship had only minutes to live, replied, "There is no need to lower them yet," and merely instructed the seaman to have them swung over the side.

Then time seemed to stand still as the Islander seemed to pause at a crazy angle, her bows awash. As Captains Foote, LeBlanc and Ferry stood side by side on her sloping bridge, they could hear the cries of terror as panic-stricken passengers began milling about her tilting decks in confusion.

For several moments the ship remained suspended, neither officer daring to contemplate the result should her bulkheads give way before the force of the sea.

The Islander's Scottish builders had done their work well but it was an impossible contest and, a quarter of an hour after striking, there came a blood-curdling groan from deep within. As she began her death plunge, Capt. Ferry looked at his old friend and sighed, "Captain, I guess we will have to go."

Together they fought their way through swaying passageways to the boat deck when, with a deafening explosion, the boilers burst, hurtling both officers into the sea. Afterwards, Ferry described his life-or-death race to the rail, recalling how he'd overheard the Islander's barber, George Miles, say to a companion as both prepared to jump over the side, "I don't know what may happen to me but if I go down and you are saved, bid goodbye to my wife for me."

Days later, the friend reached Victoria to carry out his lost shipmate's last request.

Just seconds before the boilers blew, Foote recounted, he'd noticed an old woman. Bent with rheumatism and wearing a life preserver, she'd been sitting on the deck. She'd caught his attention by the calm with which she'd obviously been awaiting the end.

The stories told by other survivors of their miraculous escapes were many and, in several cases, heartbreaking. That recited by Dr. W.S. Philips was one of outright horror, the Seattle medic graphically describing the loss of his wife and four-year-old daughter.

They'd been asleep in their stateroom when the Islander crashed into the iceberg and threw them from their bunks. Upon rushing from the cabin and battling their way towards the upper deck, the passageways were at an almost impossible angle and awash as the ship's nose was already under.

Somehow Dr. Philips and his family made it to the main deck--where their agony began.

Deep within the dying steamer the flooding seas created tremendous suction and as the terrified trio passed a large ventilator, the draft from below drew them, slowly and inexorably, to its gaping mouth. Philips was able to grasp the ventilator's lip but his wife and little daughter weren't strong enough to hold on. As he watched in wide-eyed horror, they were sucked below as the monstrous vacuum drew him steadily into the ventilator's jaws.

Then his chin struck the lip. The next he knew, he was at the rail and preparing to jump. Then the Islander slid under, drawing him down with her. When he came to he was sharing a door as a raft with two other survivors. Hours afterwards they were taken ashore where, overcome by shock and exposure as he huddled on the cold beach, he became delirious and began to call out for his family.

Suddenly, he heard a child crying and he rushed to her side. But the little girl was a total stranger.

Poor Dr. Philips' ordeal was by no means ended as, upon regaining his exposure, he joined in the task of recovering the dead who'd washed ashore with the tide. Upon dragging a body, that of a child, from the surf, it proved to be that of his daughter. This final shock was too much for the hapless doctor who fell to his knees on the rocky shores of Lynn Canal, clutching his little girl and sobbing hysterically until sympathetic hands separated them.

One of the heroes of the Islander's sinking was Second Officer Powell who, immediately upon her striking the 'berg, had assumed charge of lowering the boats without waiting for the order to do so. Calmly, methodically, he'd led frightened passengers to the boats and operated the davits until the ship began her plunge.

He shouted to those remaining to jump. Only then did he run for the railing himself--as a teen-aged girl threw her arms around his neck and begged him to save her. Seconds later, still embraced, they hit the icy waters of the canal.

But when Powell surfaced, his unidentified companion was gone.

Upon swimming alongside a nearby raft he found the float was occupied by several survivors including Captains Foote and LeBlanc. But, as Powell later testified at the inquiry, as he reached for a lifeline another survivor, a passenger, ordered him away. When he persisted in attempting to board the raft, the man drew a revolver and threatened to "blow his brains out".

Even this drastic rebuff failed to deter Powell who retorted, "Shoot away, for I guess you'll soon follow me. Anyhow, I believe your cartridges are wet."

Several other members of the Islander's crew who'd reacted heroically made the supreme sacrifice. When the liner had slammed into the ice two of the firemen had instantly volunteered to close the valve connecting the forward compartments and the engine room--only to be drowned before the eyes of their comrades.

At this, the remainder of the black gang had joined in a human chain to make a run for the deck. Just as they began their mad dash for safety, Second Engineer Allan had yelled, "If we meet, we meet, and if we don't, we don't. We'll make a bold dash for it, anyway!"

When survivors were finally brought together it was learned that all of the engine room crew who'd formed the chain had survived--all but Allan who'd been married only four months.

A second, grimmer tragedy had been enacted deep within the Islander.

Shortly after clearing Skagway, 12 stowaways had been found and put to work in the hold, passing coal to pay for their fares. Unknown to the chief engineer, these men were still in the bunkers when the steamer struck. He'd immediately ordered the holds sealed so as to slow the flooding, an act which undoubtedly saved lives by delaying the ship's plunge by several minutes.

But for 11 of the stowaways the engineer's order had meant death, only the 12th man surviving because he ran from the bunkers at the instant of the crash.

Sixty years after that fateful morning one of the Islander's survivors recalled his narrow escape from her sloping decks. Ex-Mounted Policeman Edmund Waller of Nanaimo had been en route to Victoria with two other constables after two years' duty in the Yukon and was in their cabin when the ship struck.

"We were just settling down," he said, "when we felt a jar. Then the engines stopped. A strange silence settled over the ship. There was no outcry. No shouting. We lay in our bunks and listened and wondered what had happened."

He and his companions soon realized the gravity of the situation when the ship began to settle forward. By the time they rushed topside the saloon was awash, the main deck empty, the lifeboats gone. Just then they they heard voices and made their way around "the housework to the other side of the ship. It was black dark. We could see a boat pulling away from the ship. It was the last one."

Faced with no other choice but to swim, the three leaped over the side and struck out for the departing craft, to be pulled aboard. The overloaded boat was just 150 yards from the ship when her boilers exploded. The ear-splitting roar, said Waller, was followed by screaming. Then silence.

Few of those in the glacier-fed waters of Lynn Canal survived for long and by morning the shores were littered with dead. Once the survivors were rushed to Juneau, the grim task of recovering the bodies of 42 men, women and children was begun.

At the inquest in Victoria, Second Officer Powell accused the man who'd threatened him with a revolver with having been responsible for the death of Capt. Foote. The passenger, he said, had accused Foote of incompetency and driven the dazed master from the raft. This, the unidentified passenger denied, saying that he hadn't had a gun but his pipe which he'd used to bluff those with life jackets from forcing their way aboard the dangerously overloaded float.

Capt. Foote, he said, had left the raft of his own accord. Once in the water and overcome by cold, Foote began to babble deliriously and bade them farewell several times. Then, with a final, "Goodbye, boys!" he raised his arms, allowing his lifebelt to slip up over his shoulders, and "sank like a stone".

For Mrs. Foote, the news of the Islander's sinking and of her husband's death had come with cruel suddenness, it being reported that she "was walking along the street on Sunday evening when a small boy stopped her and said, "Mrs. Foote, the Islander is wrecked and your husband is drowned."

"Dazed by the sudden shock, she went home, where soon afterwards she learned that it was all too true, for a former shipmate of the dead mariner had come to break as best he could the sad news, only to find his sorrowful tale was already known..."

After due deliberation the inquiry ruled that he Islander's company had, as a whole, acted bravely and unselfishly, that Capt. Edmund LeBlanc, pilot, was censurable for having failed to reduce speed upon seeing ice in the canal, that Capt. Foote had been negligent in leaving the bridge without giving his officers special instructions.

As a special rider to that verdict, and in response to rumours which had been circulating, the members of inquiry ruled that there was no evidence of intoxication of any of the ship's officers.

For Capt. Hamilton Foote the tragedy meant not only the loss of his ship and his life but, with the ruling of negligence, his professional reputation as well. It was an ironic turn of events for the veteran master who'd encountered ice in Lynn Canal once before.

Not two years earlier, when in command of the S.S. Danube, he'd been holed--just a few miles south of where the Islander foundered. But on that occasion, the Danube's bulkheads had saved her, Foote eventually coaxing his ship into Juneau with her nose flooded. It was thought that he'd been confident that the larger, newer Islander's bulkheads would save her that foggy morning of Aug. 15, 1901.

But the Islander had been mortally wounded and 42 persons died with her in the fog-bound reaches of Lynn Canal...

(Next week: Conclusion)

* * * * *

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.