Ernest Chenoweth: Is He British Columbia’s Youngest Murderer?

I’ve never understood the human fascination with crime but there’s no denying its universal appeal. Crime stories, particularly those about true murders, unsolved and otherwise, are the subject of movies, plays, books, magazines and websites; they’re on television and radio, and among the headliners of daily newscasts.

While none of us favours criminal activity, particularly within our own communities, most of us enjoy a “good murder story,” me (heaven help me) included. Crime and romance, polar opposites are, in fact, the two most popular entertainment genres of all.

Certainly British Columbia has and has had its share of criminal activity, some of it so bizarre as to all but defy belief. But the facts speak for themselves and the Chronicles simply wouldn’t be complete without an occasional crime story.

So said, this week I introduce you to Ernest Chenoweth. He may not be British Columbia’s youngest murderer but he’s the youngest British Columbian to be tried for murder—a particularly cold blooded one at that. He was just eight years old when he pulled the trigger then stood in the prisoner’s dock in the Nelson courthouse.

* * * * *

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of many murders isn’t the crime itself nor even the “who-dun’it,” but the motive—the ‘why.’

This certainly is true of the case of Ernest Chenoweth of Rossland in May 1900. When the identity of the murderer became known, the question on everybody’s lips was, why did he do it? Whatever would have possessed a lad of just eight years to shoot his family’s Chinese cook in cold blood?

Certainly it wasn’t the usual suspects of greed, lust or revenge.

Police and the provincial criminal authorities of the day couldn’t comprehend his logic. And, 121 years later, for all we’ve since learned about human psychology, I seriously doubt that we can comprehend, either...

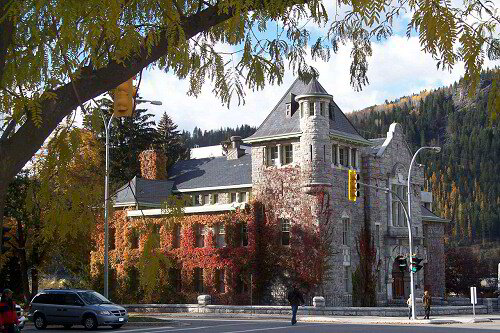

Last week I mistakenly told you that Ernest Chenoweth was tried in the Rossland where he lived. His two-day trial actually was held in Nelson whose beautiful courthouse is shown here.--www.geocaching.com

The Rossland of West Kootenay region of south central British Columbia at the beginning of the last century was young but booming and already claiming to be the third largest city in the province. This meteoric rise had occurred in just 10 years thanks to a handful of mines, in particular the Le Roi which had proved to be one of the richest gold mines in all of B.C. Which was saying something when you consider the incredible riches that other provincial mines had yielded over the previous 40-odd years. For Rossland, the Le Roi and company brought riches to some, jobs for many, and a thriving business community.

It also drew Chinese immigrants looking for work and they’d settled in in Chinatown, a typical frontier-style ghetto offside the white community. As ‘aliens’ of second and third-class status in colonial society, they had to offer their services for lower pay if they wanted a job, any kind of a job. This put them on a collision course with the white worker majority who, fearful for their own welfare, bitterly resented and feared the competition.

Not that it stopped people from hiring them, of course. Why not, when they could have hard working labourers or domestic help for half the going wage of one of their own? So it was in the case of the Chenoweth household and cook Mah Lin.

The Chenoweth family was hardly rich but didn’t need to be to have domestic help, thanks to the desperate need of the Chinese who’d work at almost any price. So what that they lived in a four-room shack. There, on 3rd Ave., Ernest resided with his mother Mary and two stepbrothers, Roy and Merton Stephens, 19 and 17. A third brother, Hugh, 14, had already left home and there was no Mr. Chenoweth, Mary’s second husband, having deserted them the previous year.

Which was just as well because the house was so small that the rooms would have been claustrophobic with five occupants. Even four, three of them adults, made for a tight fit. The kitchen in which Mah Lin worked was only 63 square feet—nine feet by seven feet, smaller than most bathrooms of today—and of the rest of the house, there was a dining room and the parlour which doubled as Mary’s bedroom, the bedroom serving all three brothers.

Within weeks of the tragedy, for $16 per month drawn from the wages her older sons earned as miners, and from her own small wage working as a cook at the Allan Hotel, Mary hired Mah Lin to come twice daily to make her sons’ morning and evening meals. So it was, on the fateful afternoon of May 23, 1900, that he arrived on schedule to set to work in the tiny kitchen to cook their suppers.

Ernest was playing in the yard when he arrived at 4:30. Just an hour later, Mrs. Louise Aylward, a friend and neighbour, stopped by to visit and spotted Mah Lin’s body through the window. Thinking he needed medical assistance, she entered the house; he was lying on the kitchen floor, covered in blood from what would prove to be a bullet wound in his head. On the stove, a pot of potatoes was boiling over and she calmly removed it before calling for help.

Rossland Chief of Police Jack Ingram immediately began an investigation but, initially, there was little to go on in the way of clues other than that the cook been shot at close range and had died instantly. This had only been determined after the two doctors who attended wiped his forehead and exposed the wound. There was so much blood on the body and the floor that their initial surmise was that he’d died of a hemorrhage.

What struck Ingram most was that there were no signs of an intruder and the shot hadn’t been fired through the kitchen window. Mah Lin had been preparing dinner—a boiling pot of potatoes was still on the stove and beans were spilled on the floor. The murderer had had to have been standing in the entrance to the kitchen from the dining room.

A rifle in the boys’ bedroom, owned by Roy, had recently been fired but all of the brothers, including Ernest, had used the gun for target practice and this was before ballistics tests could match grooves on a lead slug to the barrel of the gun from which it had been fired.

With no immediate motive or suspect at hand, a coroner’s jury had little choice but to rule that Mah Lin had been shot to death by a “person unknown”.

Popular rumour inspired by the racial mindset of the day had it that he’d been murdered by his own countrymen, that he was a victim of the tong rivalry for which Chinese immigrants were said to be notorious. Stung by a headline of the Rossland Miner—“A Chinaman [sic] Did The Deed,” followed by the ludicrous statement that “a deliberate murder of a Chinaman by a white man is out of the question,” the Chinese Benevolent Society pressed Chief Ingram to solve the case. Stymied, although he’d already formed a theory of his own, Ingram more or less left it to the famous Pinkerton’s Detective Agency to solve the case, they having been called in by the Provincial Police.

Ingram didn’t believe the tong angle for a moment. But who then?

There were no witnesses, Mah Lin having been in the kitchen alone, young Ernest playing in the front yard. Was it possible that someone had entered the house through the back door unseen, fired the fatal shot and disappeared without Ernest hearing or seeing anything?

Or was it more sinister than that—one or both of the older Chenoweth boys, say, when they came home from work expecting their dinner?

Was there an argument? One of such fury that it ended in gunfire? Ingram had formed a low opinion of the family: the mother, in his mind, was just short of being a prostitute, and the two older sons, well, they were real toughs. They weren’t your typical respectable working class family.

But why shoot Mah Lin? For this Ingram didn’t have the answer but he was convinced that eight-year-old Ernest was the key. He’d been playing in the front yard, it was a small house. Surely he’d heard or seen something. Was he covering up for his brothers?

There was the rub: how to find out. Ernest was a child. He couldn’t just be called in for questioning like any other criminal suspect. How could Ingram interrogate him and get him to talk?

Two months went by before Ingram realized that the answer was right in front of him: the Pinkerton’s Seattle supervisor, P.K. Ahern, who was conducting the case personally. Ingram would, unofficially, ask Ahern to question Ernest. Ahern, who was also sensitive to Ernest’s age, agreed to do it but decided to play it safe by taking along one of Ingram’s officers. Together, they called upon Mary at her hotel job and somehow—one can’t help but wonder what they said, threatened or promised to persuade her—got her permission to let them take Ernest down to the basement and question him. Ahern promised he wouldn’t take more than half an hour.

It’s Ernest’s tender age that we have to keep in mind here. He was just a child and obviously didn’t think and act as an adult. Young or no, he could also be expected to show family loyalty. If Ingram was correct that one of the older brothers shot Mah Lin, he was in effect asking Ahern to get Ernest to inform on his own kin. And what did Mary stand to gain from this? Each or all of her sons were under suspicion; if any or all of them were charged with Mah Lin’s death, she stood to lose one, two or, heaven forbid, three sons.

The fact remains that, willingly or otherwise, she let Ahern and the policeman take Ernest downstairs and, in the privacy of the hotel basement, interrogate him—not for half an hour as promised, but for four hours. It only ended then because Ahern had what he wanted—Ernest had talked.

Not of covering up for his brothers but of having shot Mah Lin himself.

Ahern—an American private detective, remember—then had Ernest sign a dictated confession. Coming from the lips of a young boy it’s all the more chilling for its coldblooded tone that would become positively boastful over time. Also startling is that Ernest appears to have shot Mah Lin almost for the joy of it and not only showed no remorse, but smirkingly described the last few moments that passed between himself and the cook who was preparing supper when Ernest entered the kitchen with a loaded rifle.

Originally, he’d told police that he was playing in the front yard when Mah Lin arrived. In his confession, he stated he was actually watching a neighbour’s chickens a little after 4 o’clock on the afternoon of May 23:

“I remember it was the day before the Queen’s birthday. I saw Mah Lin, the Chinaman employed by my mother as cook, enter the kitchen by the back door. I went in by the same door shortly afterwards and he was slicing potatoes.

“I said to Mah Lin, ‘I killem you.’ meaning I kill you.

“I left the kitchen and passed through front room into the bedroom, and took a .32-calibre Remington rifle which belonged to my brother Roy, which was standing in the corner of the room at the back of the bed, and left the bedroom and passed into the front room. Before going into the front room and while I was on the bed I raised the trigger and snapped it, then I went towards the Chinaman Mah Lin.

“I said, as I raised the gun and aimed at him, ‘Now, here you go, John.’

“I then pulled the trigger. I was standing near the door of the kitchen. He smiled as I said, ‘Here you go.’ He had a dish of beans in his hand. I pulled the trigger and he fell towards me, his head towards the front room door. He kicked around, and there was blood running from his mouth and nose. He did not speak, but made a gurgling sound. Then I put the gun back where I found it, and then went to the kitchen and said, ‘Did I kill you, John, did I kill you?’

“I then ran out the back kitchen door and went down towards the [railway] depot, and met Johnnie Perry there at the depot. I then went down Lincoln Street, and met my brother and Mrs. King coming up from town. I did not tell her I killed Mah Lin, but I killed him. I didn’t want to tell her for fear she would whip me. I told my mother about it before the inquest in court. She told me not to say anything about it. She was the only person I told of having killed him. I put the gun back in the corner again after I shot him. I was standing in the dining room when I shot him.”

The signed confession, the one that was dictated for transcription by Pinkerton’s Detective Ahern and dated July 22nd, was later signed and witnessed by Edward Bowes, Coroner, and F.E. French and Dan McDougall as witnesses.

At its conclusion, Ernest was asked if he had been afraid when he shot Mah Lin. His answer is so callous that it leaves us to ponder how one so young and who, without any known previous engagement with the Chinese citizens of Rossland, had already developed a fear bordering on paranoia for their race. Did his older brothers poison his mind? Poor Mah Lin’s only sin, it seems, in Ernest’s eyes, was that he was a despised Chinaman and the Chinese were to be feared.

As for having been “much scared” when he shot the cook, he replied, “No, not much. I was glad one Chinaman was out of the way. I was afraid of the China[men] for fear they would kill me. That was the reason I didn’t tell the truth at the investigation. He smiled at me when I pointed the gun at him, but the smile left his face mighty quick when I shot him.”

His trial was held in Nelson in August before Justice G.A. Walkem. Twice Ernest and mother Mary took the early morning train and didn’t get home until evening. Seated in the prisoner’s dock, Ernest amused himself by playing with toys he’d brought with him.

No doubt because of the singular circumstances of the case, which was widely publicized, the deputy attorney general led for the Crown. But he did so with his hands tied. He couldn’t use Ernest’s confession because of its questionable origin, the possibility of duress, and because Ahern had indiscreetly (and obviously without authority) assured Ernest that it wouldn’t be used in court. And, speaking of Ahern, whose testimony about how he obtained the confession was vital to both prosecution and defence, he refused to make himself available for the trial.

All the Crown had to go on was the medical evidence indicating the killer had to have been inside the house when he shot Mah Lin, the unproven probability that the murder weapon was Roy’s rifle, and the testimony of several city workers who claimed that Ernest had bragged to them, “I never saw a son-of-a-bitch die as quickly as the Chinaman.”

And: “The Chinaman can not stand much shooting. He fell like a log.”

Was this just childhood bravado?

After two days of listening to various witnesses, the jury didn’t even have to leave the courtroom to give their verdict of Not Guilty.

Such is the story of Canada’s youngest person ever to stand trial for a capital crime.

The obvious question that comes to mind is, whatever became of Ernest Chenoweth? Did he go on to become a hardened criminal, a mass murderer? Or did he try to redeem himself? Neither, so far as is known. In 2012 Rossland Telegraph columnist Alyyson Kennie revisited the murder of Mah Lin. She learned that Roy Stephens, who continued to live in Rossland after the murder, had received a postcard from his younger stepbrother in 1925. Ernest was alive and well and living in Chico, Shasta County, Cal., where he was a member of the Socialist Party.

He was still only 33 years old in 1925. What became of him thereafter remains unknown, alas.

* * * * *

In 1993 retired Duncan lawyer, author and historian David Ricardo Williams told the story of Ernest Chenoweth and Mah Lin in his book, With Malice Aforethought: Six Spectacular Canadian Trials. In his review of the book, Andrew Fong of Chinacity Books, Edmonton, noted the case’s socio-political backdrop and summed up, as had Williams, why the prosecution’s case had been doomed from the start:

“In most instances, [a confession such as Ernest’s] could be tendered at an accused's trial. In Canada, however, no statement made out of court by an accused to a person in authority over the proceeding against him can be admitted into evidence unless the prosecution can show to the satisfaction of the trial judge that this statement was made freely and voluntarily. The statement in the case of Chenoweth was ruled inadmissible and, in the end, the jury was never made aware of its existence.”

This had doomed the case for the prosecution from the outset, the prosecutor at the preliminary inquiry had no enthusiasm for prosecuting the case; even the judge who presided at the preliminary inquiry didn’t want to order the accused to stand trial in the B.C. Supreme Court. Instead of dismissing the charge outright, he “took the highly improper step of referring the question to the Attorney General. The Attorney General, in turn, through his Deputy, asked the preliminary inquiry judge to commit the accused to stand trial. The trial judge reluctantly agreed...”

After two days “the trial judge's charge to the jury left no doubt in their minds that they should acquit."

Would a capital crime involving an eight-year-old child have a different outcome today? Mr. Fong didn’t think so, noting that today’s Young Offender Act has a cut-off age of 12 (that is, the accused’s age at the time of the offence). Besides, in this particular case, Ernest’s alleged confession would never be admissible by today’s standards.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.