Exploring a Railway Legacy

Guest column by Tom W. Parkin

Photos © TW Parkin

*****

B.C. history faces increasing challenges. Historic sites and museums are experiencing funding cuts, public figures who shaped our past are losing recognition, and railways that once built nations are being abandoned. Vancouver Island’s Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway (E&N)—although it’s not even called that anymore—is a prime example. Its last spike was driven in 1886 by Robert Dunsmuir and Sir John A. Macdonald. Today, just six miles of track within the City of Nanaimo remain in service.

Yet, where trains no longer run, people are finding new purpose for the track. Walking the rails has become a way to connect with history and appreciate an industry on the brink of disappearance. This guide highlights four accessible sections of the E&N, each with its own character. Along the way, I’ll share practical tips and historical insights.

Lace your boots, grab your camera, and let’s meander through southern Vancouver Island’s scenic and storied landscape.

(Bearing in mind that, legally, you’ll be trespassing. Readers are urged to use their own discretion. See this week’s Editorial for my own view of this.—TWP)

Before you begin, it’s important to know this railway’s right-of-way remains private property, and walking there is technically trespassing. In some areas, parallel trails have been established by local governments as alternatives. These descriptions, however, are for those drawn to sections where no trains have run for over a decade.

Stay safe and oriented by using maps on your phone. Watch for maintenance workers—they’re rare but worth treating with respect. Be cautious crossing roads and bridges, and note that railways measure distances in miles, not kilometers. Many structures and signals still bear mileage markers, referencing Victoria’s former station as Mile Zero.

* * * * *

Mile 35.5 to 37.9

Koksilah River section

Koksilah area

This 2.4 mile length of track has particular appeal for scenery, much of it running past the Koksilah River and hay fields. The route stretches between the former flag stop of Cowichan Station in the south and Miller Road crossing in the north. Miller Road is located directly across Highway #1 from The Old Farm Market.

Approaching Koksilah River E&N bridge in a frosty November morning. — © TW Parkin

Near the south end, Bright Angel Regional Park (https://www.cvrd.ca/150/Bright-Angel-Park) can be used as a rendezvous for those arranging pick-ups or drop-offs. It provides a well-maintained area for lazing about, picnicking, and excited children. If you prefer, a suspended footbridge over the river from the park to the railway can be used to cut off 0.9 mile of walking south to Cowichan Station (near Koksilah Road).

Koksilah Road at Cowichan Station. These abutments are sawn from sandstone, which replaced much timberwork when the C.P.R. first came to the Island. — © TW Parkin.

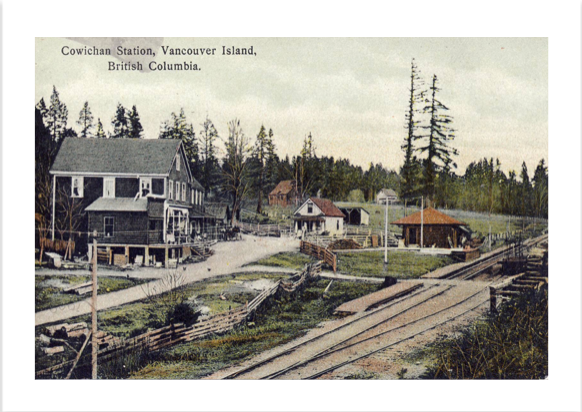

Cowichan Station as it appeared on a postcard at the beginning of the last century. Published by the local general merchant, who must have had great pride in, and dreams for, his establishment. —BC Archives

A passenger shelter at Cowichan Station bears a sign dated 1885, but means only that it stands on the site of the original shelter. After this you can picnic in a small riverside park beside a timber truss over Koksilah River. You won’t find many of these Howe trusses left in B.C., so take a walk across to admire this piece of forgotten B.C.

If you don’t want to walk this entire length of track, consider visiting an interesting steel through truss over the Koksilah River, just 0.2 miles south of Miller Road. This “basket handle” design was erected here in 1940. Like other CPR bridges, it was brought in after prior service elsewhere. A similar structure over the Tulameen River near Princeton still serves on what is now the Kettle Valley rail trail, so this Island bridge may once have been on that line.

Koksilah River bridge shows distinctive “basket handle” arches. One of the side-pipes is a conduit carrying TV cable. —© TW Parkin

* * * * *

Mile 39.3

Cowichan River bridge

Duncan

CP’s vintage Fraser River (Cisco, B.C.) bridge now erected over the E&N’s Niagara Canyon garners more attention, but this Cowichan River truss is more easily reached and has an even longer history. It dates from 1876 when bridge iron still incorporated Victorian flourishes like flower designs “just for pretty”.

Its designer was New Yorker Squire Whipple, and he was among the first engineers to understand the stresses which cause trusses such as this to ‘work’. Thus, it’s called a Whipple through truss. “Through” simply means it carries its load within its own structure, rather than, say, over it.

Ye ol’ swimmin’ hole beneath the Cowichan River bridge, Duncan. The structure was forged 148 years ago. Photo © TW Parkin

The manufacturer in this instance was Phoenix Iron Co. of Philadelphia, which made this span for the Pennsylvania Railroad at a location near Altoona, PA. Becoming too light for that purpose, it next helped the CPR cross the St. Maurice River in Québec, in 1892. The CPR moved it here in 1907 during upgrades to the line following its purchase of the E&N from the Dunsmuir family.

It reminds me of a Meccano erector set that I played with as a boy. That this bridge still stands is testament as to how well things were designed and built in an earlier century, long before modern metallurgy. The vertical columns, embossed with the Phoenix name, were patented structures which could bear more weight than previous designs.

Detail of Cowichan River bridge. I’m reminded of the Meccano set I had as a boy. Whipple trusses such as this gained popularity with railways because they had superior strength. —© TW Parkin

At one time, the CPR was mocked as “the Cheapy R” in recognition of its thrifty nature. Whether by design or happy accident, the railway has preserved one of the most significant heritage bridges in Canada, and the only Phoenix through truss. It's a piece of history few expect to find in Duncan.

For more information, also see Turner and MacLachlan’s authoritative The Canadian Pacific’s Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway: the CPR Steam Years, published in 2012.

The bridge and the river are on land claimed by the Quwʼutsun Nation, but everyone can splash in the river, come summer.

* * * * *

Mile 57.3

Holland Creek culvert (20 feet)

Ladysmith

Substructures are as interesting as bridges because the oldest of them involve the lost craft of stonemasonry. When the C.P.R. took over Dunsmuir’s aging system, it knew his wood structures needed stone and steel replacements.

This site is reached from a sharp turn onto Roland Road, itself off Chemainus Road. Drive straight past Pamela Anderson’s house and park on the left shoulder at the corner nearest the tracks. A five-minute trail takes you to where Holland Creek enters Ladysmith Harbour. In the fall, chum and coho salmon pass through a culvert here to spawn upstream of Highway #1.

The high embankment above this culvert’s portal was originally a timber trestle in 1886, following the standard practice of prioritizing speed and economy. It wasn’t until 1908, after James Dunsmuir sold the railway, that a lasting sandstone culvert replaced it.

The handsome culvert of locally quarried sandstone.—© TW Parkin

Like the underpass at Cowichan Station, this culvert is built from sandstone cut from the quarry near there. It was used in many bridges and culverts along the E&N line prior to the introduction of concrete. The strategy with culverts was standard: assume the creek is naturally in its ideal position. Divert it temporarily so stone blocks can be built over a sturdy formwork, forming an arch stabilized with precision-cut keystones. Loose gravel was then dumped from rail cars leaving no trace of the timber’s existence as the fill became the new foundation for the track.

Once done, remove the formwork, pave the stream bed to prevent erosion, and route the creek back into its original position. With the creek under control, gravel would be dumped from rail cars on the trestle, gradually burying it until its crossties were supported by the fill itself. If any fill settled with time, another ‘lift’ of gravel was added until all was level again.

To continue hiking, drive back across Hwy #1 and park at the shopping centre. Behind Save-on-Foods, choose a trail on either side of Holland Creek and hike uphill to the nearest footbridge. Return on the far side of the creek for variety. The town keeps it all in good condition, and the route is popular.

* * * * *

You won’t have to be looking over your shoulder when you hike the E&N today. No steam ;ocomotives of old, not even the diesel-powered Dayliner is going to disturb you. Very rarely, an ICF maintenance vehicle.—BC Archives

Mile 86.8 to 89.6.

Nanoose S-bend

Nanoose Bay

Ladysmith Standard Saturday, 11 July 1908

VICTORIA, B.C., July 8. — Twenty miles of seventy-two pound rails are expected to reach Ladysmith any day for shipment from Wellington [today in urban Nanaimo] thence to the western terminus of the new trans-island railroad which will connect Nanoose Bay and Alberni, effecting a junction with the E.&N. line. These will be laid without delay on the first section of the grading which, it is reported has practically completed for the initial twelve miles … The weight of the rails to be used on the road to Alberni, the new western terminus of the C.P.R., is considerably above those now in service on the E. & N.

This rural mileage has four road crossings, creating optional short returns should you want off the track for any reason. Northwest Bay Road also passes two service centres where food and drink may be purchased. Use Google maps to understand the lay of the land. Turn off Highway 19 at Nanoose Beach Road and park away from the rails and off the road. Start walking to the north.

Nanoose Beach Rd 86.6 X-ing.

Nanoose station 86.7 Former siding, 982 feet, park here

Bonell Creek 86.8 66-ft deck plate girder, 1909

NW Bay Road 1 86.9 X-ing

Nanoose Creek 87.2 46-ft deck plate girder, 1909

NW Bay Road 2 87.8 X-ing

Powder Point Road 88.1 X-ing

NW Bay Road 3 88.6 X-ing

Private X-ing 89.0 No public access

Sanders Road 89.9 North end, Bryn siding

The core of this pastoral walk is barely two miles, one way. These end points are Nanoose Station Road and Northwest Bay Road crossing #3, but extensions from either end are possible. The grade rises gently with the rising mileage, and passes through an area of rural acreages with curious sheep, alpacas, and the occasional backyard dog. The encroaching natural vegetation still allows walkers to pass without getting snagged in broom or blackberries. Birders and wildflower photographers may find subjects of interest.

Back at the beginning (Mile 86.7), south from Nanoose station (toward Nanaimo), the track parallels the shore of Nanoose Bay. For those seeking a longer walk, this extension offers views of tidal flats, oyster farms, and ships at the Canadian Maritime Experimental & Test Range across the water.

From NWB #3 to the north, the route is less scenic. After a mile it reaches the former flag stop of Bryn*, now marked by two derelict buildings and a 1,434-foot siding. Its north end reaches a switch at Sanders Road, where walkers might pre-position a vehicle for their return drive (3.1 miles by road). First though, slake your thirst at nearby Rocking Horse Pub! With good timing, you can also catch a southbound bus back to the Island Highway #19. Check its schedule on Regional District of Nanaimo transit route #91.

*Bryn is short for Brynmarl, the name of a former post office which operated intermittently here. Brynmawr is Welsh for "high hill”. This name must have come about because this is the top of the rise which the railway has to climb using an elongated S-bend.

* * * * *