Father Pat, ‘Hero of the Far West’

“The life of a missionary priest in Canada amongst settlers is not often an eventful one. It generally presents a record of hard, monotonous work like that of a poor priest in a scattered agricultural parish in England. There are, however, some points of difference...”

So wrote, in 1909, The Right Reverend John Dart, D.D., Bishop of New Westminster and Kootenay, in his preface to Mrs. Jerome Mercier’s forthcoming book, Father Pat: A Hero of the Far West.

Of B.C.s many dedicated men of the cloth, Father Pat Irwin was one of a kind. —www.anglicanhistory.org/canada

Having read numerous biographies of B.C.’s pioneering missionaries of various faiths of a century and more ago, I want to argue with Bishop Dart’s tepid testimonial to his peers. But not today. He did acknowledge that the Canadian priest must cover “much longer distances both walking and riding, and he must be more frequently away from home.”

Ergo, he needed to “be decidedly hardy and athletic”.

But that doesn’t even come close to the human requirements of missionary work on the Canadian, in this case the British Columbia, frontier. Most of those who accepted the call to carry their church’s message to the wilderness met Dart’s physical criterion. The real test was to the missionary’s character, to his (they were all men in those days) mental and spiritual strength.

Not just for the immediate, or even a commitment of several years, but for a lifetime.

And this is where the Anglican Church’s ambassador Rev. Henry ‘Pat’ Irwin stands head and shoulders above many. He was nothing short of extraordinary both as a man and as a priest. That he should have suffered such a sad ending must be one of the crueller ironies of B.C. history.

The good bishop came closer to the mark when he wrote, “It was because Henry Irwin always showed himself to be unselfish, sympathetic, and anxious to help others to the very utmost of his power, that he won his great influence amongst the pioneers of British Columbia and that his name and memory are held by them in affection and respect...”

But that small tribute, like the proverbial tip of the iceberg, only hints at the real Father Pat Irwin.

* * * * *

In his preface to Anne Mercier’s biographical portrait, Bishop Dart wrote that, soon after his arrival in B.C. in 1895, he received a letter from Irwin, then living in Ireland, offering his services to the diocese. As he’d already served as a missionary in the booming gold town of Rossland and as chaplain to Bishop Sillitoe, he “seemed, from the reports that reached me, to be just the man for the place.

“Accordingly, he was sent there, and the result answered my expectations....”

This is where Dart hints at the real Rev. Henry Irwin whom miners knew affectionately as Father Pat: “Very soon a spacious frame building was erected for a church, with rooms in the basement to serve as a lodging for the priest and a club for the men in the neighbourhood. But I do not remember ever finding Irwin in his own rooms. They were always giving shelter to poor people who had been reduced to want, whilst he himself had a shake-down in some friendly bachelor's ‘shack.’”

When Rossland became more civilized, as Dart put it, Irwin, missing the more rough-and-tumble frontier life of a mining camp, and its earthier citizens, chose to “take up pioneer work” in the Boundary Country. What followed were experiences and adventures and, finally, tragedy enough to fill Mrs. Mercier’s 108-page book.

For the purpose of the Chronicles, the challenge is try to convey the essence of this remarkable pioneer within strict space limitations. In short, readers will have to trust to my cherry picking this and cherry picking that to, hopefully, present the Rev. Henry Irwin—Father Pat—who truly was.

* * * * *

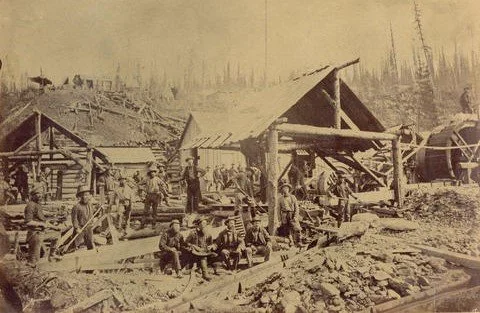

The CPR station in the boom town of Donald in 1887. Father Pat felt right at home among the work-hardened and worldly-worn navvies. —Wikipedia

Almost from the start, Henry wanted to be a missionary. The eldest of four brothers born in August 1859 “among the Wicklow Mountains,” 30 kilometres from Dublin, such an early ambition wouldn’t have surprised a family with three generations of church service. It’s said that his temperament ever hinted of a generous nature, of an innate need “to do something”.

He loved people and animals, was generous and forgiving, athletic and physically fearless as he explored the countryside on horseback. These were the qualities that his brother would later attribute to his success on the Canadian frontier: “All through his school and college life he studied to train and harden his body in all kinds of manly exercises, always with the one end [missionary work] in view.”

Aged 12, Henry enrolled in St. Columba’s School (now College), the Irish Eton, where he devoted himself to his studies and sports while showing religious devotion, “always taking the right line, as if by instinct, in matters of discipline, such as bullying and protection of the weak, and in matters of moral tone”.

A diligent if not gifted learner and star cricketer, he reaffirmed to fellow students and teachers his wish to become a missionary “in a cold climate”.

Following matriculation at Keble College in 1878, he continued to demonstrate his character: “Upright and clean in nature, full of spirits and goodwill, studious, but not attaining to a high rank in scholarship, he was every man's friend, and universally loved and trusted.”

Ever the athlete, he continued to excel in cricket while taking up football and competitive rowing, and joining the college’s Missionary Association. By this time known to friends as Pat because of his Irish origin, he graduated in 1881. During a year and a-half as master of a boys’ school at Yarlet, his restlessness was apparent.

“His ideas of the future had not then taken any very definite shape,” recalled Rev. Walter Earle. “His heart was always hot within him, and he threw the whole of that heart so much into the immediate present that it was absorbed in his life with the boys, their work, their play, their everything.”

Described as a man of large sympathies, sunny, patient, untiring, earnest and loving, blessed with “a vigorous healthy body and sunny nature,” he was the ideal schoolmaster who always saw the better side of everybody's character, every boy’s real friend and helper. "His life [here] was naturally made up of (so called) little duties, but he was too thorough a man not to find a full sufficiency of greatness in the daily drudgery... I cannot remember a grievance or rub; all was outspoken, nothing misunderstood, offence impossible.

"It was a cloudy sad time when he came to tell us that he had made up his mind to take Holy Orders and devote himself to parochial work; but his mind was a strong one, and what he meant, his resolution soon put into doing.”

“...I felt he saw a larger future, and that his spirit had subtle powers and latent capabilities that ought to be free to choose what range they fancied.”

As it happened, the Rev. Earle, who so clearly recognized Irwin’s strengths and virtues, also saw his fatal weakness: “...I quite believe[d] that he would wear himself out with work: he could not understand any half measures: 'all in all, or not at all,' was his motto.”

Not until he learned of Irwin’s death did Earle realize that he’d predicted his friend’s ultimate fate.

* * * * *

Here, I’m going to fast-forward to the start of Irwin’s career on the B.C. frontier. After being ordained he taught briefly at Rugby until the spring of 1885 when he offered himself to “labour in the distant diocese of New Westminster”. Not among the Native population of a cold climate as he’d dreamt of in childhood, but among his own kind, immigrants.

Biographer Mercier: “What led Henry Irwin to select this special field for his labours, we do not exactly know, though it is said to have been suggested to him by a sermon which he heard... After correspondence with the Bishop, Acton Windeyer Sillitoe, it was decided that [he] should begin work in Kamloops on the...Canadian Pacific Railway, as assistant to Mr. Horlock, the Vicar, and thither he proceeded in 1885.”

If the diocese of New Westminster sounds “civilized” to us today, it wasn’t so during Father Pat’s time—an area as large as France, larger than the United Kingdom.

Kamloops at the time of his arrival didn’t even have an Anglican church; services being held in the courthouse, and railway workers were a motley mix of nationalities, characters and backgrounds, “many of them wild and rough”. For all that, his natural good nature and humour quickly endeared him to most as Father Pat.

A former school chum said of his ability to earn respect and to make friends: “He was always the same straightforward, simple, fearless, true-hearted character; and it was this simplicity and utter fearlessness that gave him the power which he possessed, especially among men of the roughest class, and made him attractive to a very large circle of friends.”

Kamloops is cattle country where, in Irwin’s time, the men were men and even some of the horses were out to get you. —BC Archives

There was another side to this man of the cloth—stubbornness. He graphically demonstrated this refusal to accept or to admit defeat when local wags introduced him to a stallion that was notorious for trying to maim or kill those who dared to ride him.

Kamloops is cowboy country and this adventure began with Irwin being asked, in seeming innocence, if he could ride a horse. When he said he was “born in the saddle” and had ridden many horses, saddled and bareback, in Ireland, he was invited to demonstrate his skill with the stallion—which immediately bucked him off. Although shaken, Irwin insisted upon trying again, with the same painful result.

He was about to try a third time when friends interceded and told him he was being gulled.

By this time even his tormentors were impressed with his pluck and never again was he called “milksop,” even behind his back.

He found B.C. air to be “light, bracing and health-giving”—which was just as well, as he was required to cover the surrounding territory on horseback in all weather conditions.

In a letter home he gives a clue to his work.: “The year and a half I have been here I have had fairly hard but the pleasantest of work. Most of the time I have been in the saddle. Our district is so large, and the population so small and scattered, that there's nothing for it but galloping from Sunday to Sunday, and often on Sunday itself we have fairly long rides between services...

“I cannot tell you how miserable it is meeting men from the mines who have lost their all, tramping over the country with their blankets on their backs, and not a cent in their pockets, getting a meal here and there for love, and trying to obtain work."

Only a relatively few struck it rich in the gold fields; for those who didn’t, as Father Pat well knew, it often meant poverty and hunger. —BC Archives

Even a great heart such as that of Father Pat recognized that not all were worthy of sympathy, there being those who preyed upon their fellows. But such was life; he had his hands full building a church “here in Donald, a little railway town of 600 men, and if you know any people who would like to give us help towards furnishing it, I should be thankful for the smallest trifle”.

The proffered “trifle” duly arrived in the form of modest funds, a brass cross for the altar of St. Peter's Church at Donald, a silk veil and some linen for use at celebrations of Holy Communion.

In another letter, dated Kamloops, August 19, 1887, he wrote: "Thank you for the clothes, which arrived safely and are a great blessing to me. You cannot think how nice it is to feel respectable out here, where one has to put on, and up with, almost anything in the way of coats. There is no great symmetry, as you know, in ready-made clothes, and when a parson has only the rainbow colours to choose from it is hard to be quite sombre, and certainly there's little in the ready-made clothes here of the dim religious light.

“You would hardly know me in many of my costumes.

“Last trip I started with those riding pants you sent me, but after about 300 miles they went to pieces, and I had to get into a vile kind of garment they call overalls, striped like the zebra, and cut like a sailor's pantaloons. You would open your eyes wide to see a parson at work out here...”

B.C summers were quite unlike those at home: “...It is hot, and no mistake; up to 101 in the shade. But after a certain amount of broiling one's skin gets quite hardened. I am now as hard as a cake and a browned one at that. You can guess that one has a benefit when you have to ride from early morning till the evening under a sun like ours, and that for perhaps a month at a stretch.

“I finished in June a trip of 570 miles in the saddle, and by the end of that time I was a dirty brown, very like an Indian... I think that the longer I live here the more I wonder why people leave quiet peaceful homes in the old country to rough it in Colonial life. There is absolutely no comfort here for the first five years, and a man must have quite a small fortune with him to give him a good enough start to make a home in that short time.

His muse about “why people leave quiet peaceful homes in the old country to rough it in Colonial life” appears to be as close as Irwin ever came to complaining of his chosen life or to expressing homesickness.

(To be continued)