Forgotten and Forlorn: the Ghost Town of Donald, B.C.

In February, Chronicles readers met guest columnist Tom W. Parkin (TW2 here at the BCCs.ca) who wrote about hiking a stretch of the beleaguered E&N Railway.

I’m pleased to say that he’s back this week with a photo feature on the little-known B.C. ghost town of Donald, a construction camp during the building of the CPR.

The cemetery at Donald was established in the mid-1880s, alongside the construction of the CPR’s transcontinental line through the valley. Donald flourished briefly, its future once looking bright, only to fade away almost as quickly as it arose. This burial ground is a poignant reminder of how transient life and prosperity can be. —Photo © TW Parkin

Guest column by Tom W. Parkin

Forlorn and forgotten; these were the words that came to mind during my last visit to the overgrown cemetery at Donald, B.C. As Tom Paterson has observed, cemeteries hold a unique allure. I’m often drawn to them, even when I don’t expect to recognize any names. Sometimes I stumble across people whose names I do recognize from historical reading.

Exploring these quiet places deepens my understanding of British Columbia’s history and provides a tangible connection to the past. It’s why I’m sharing this story of a secluded cemetery tucked away in the forest at Donald.

Perhaps it will inspire you to stop and explore the site the next time you’re travelling the Trans-Canada Highway—though only in summer, when the area is accessible.

* * * * *

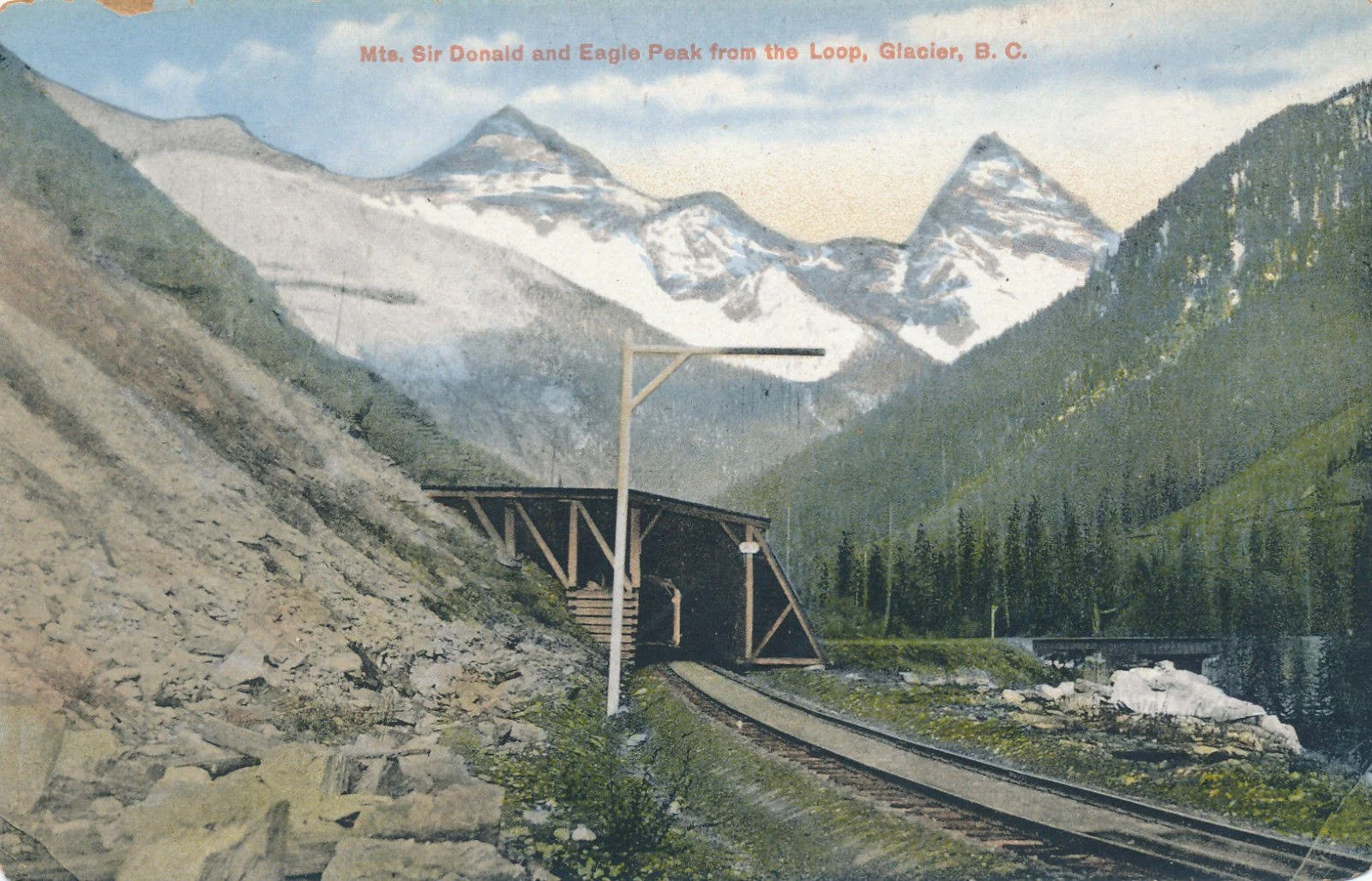

Mount Sir Donald on the right skyline. The post in the foreground suspends a “tell-tale,” a safety device of ropes hanging from its horizontal bar. These ropes would brush against a brakeman walking on the roof of a moving train, warning him to duck to avoid being struck by an upcoming obstruction—such as the snow shed seen here. ——Postcard, circa 1910.

* * * * *

Forlorn and forgotten, but not forsaken. While many wooden headstones at Donald have succumbed to time and weather, sporadic upkeep suggests that dedicated individuals are determined not to let this legacy vanish into the undergrowth. The headboards offer glimpses into the lives and times of the people buried here, with their inscriptions, symbols, and carvings reflecting culture, faith, and family connections.

I’ll never forget the moment I discovered my great-grandparents’ names for the first time, engraved on a granite spire in Ontario. It was a discovery no one in my family had made, revealing where our ancestors came from and where they now rest. I even have a photo of myself embracing their gravestone, overcome by a profound sense of connection to people I’d previously known only through genealogical research.

It was my passion for railway history that drew me to Donald, once a Canadian Pacific Railway (now CPKC) divisional point.

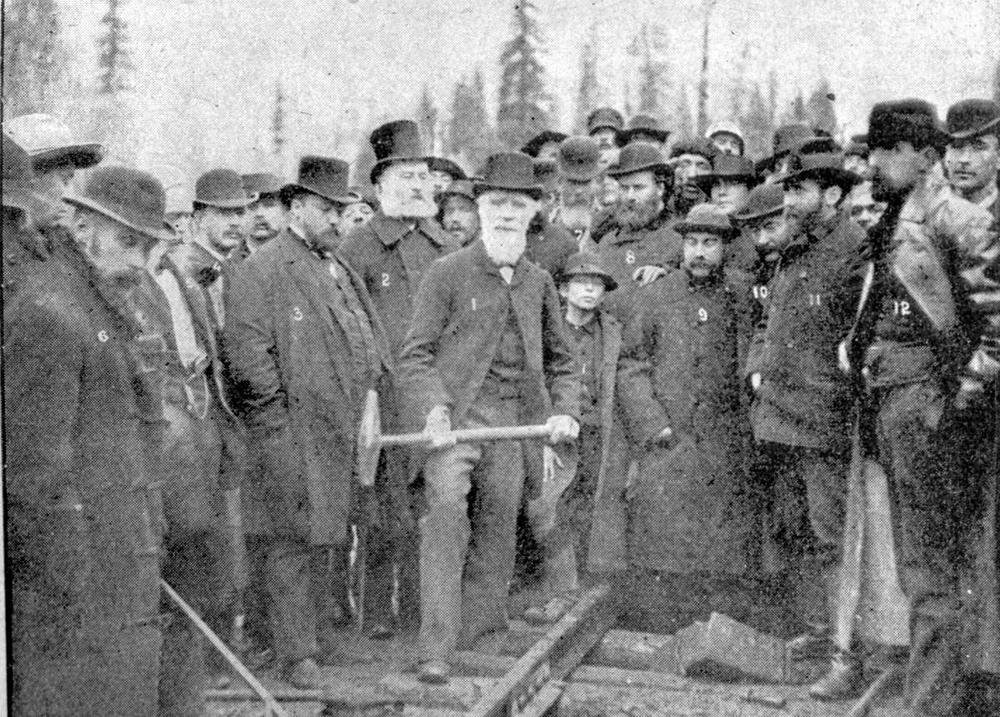

Donald was named for Sir Donald Smith, the Scottish financier who famously drove the Last Spike at Craigellachie, BC. Smith was instrumental in the CPR’s early success, and Mount Sir Donald, towering over nearby Glacier National Park, also bears his name.

One of the most famous railway photos of all time, showing Sir Donald Smith driving the Last Spike of the Canadian Pacific at Craigellachie, Nov. 7, 1885. —BC Archives

Though Sir Smith isn’t buried here, I feel a personal connection to this remarkable man—he once owned Colonsay, the Hebridean island from which my ancestors left for Canada in 1859.

CPR roundhouse and crew at Donald, circa 1887–89. Water barrels can be seen on the roof for fire-fighting purposes. In those wood-burning days, the funnel-shaped stacks on locomotives, such as the one on #376 seen on the turntable, were designed to catch sparks. The tender is piled high with cordwood, ready for the journey.

Two dogs are also part of this group, which appears to include nearly everyone in the vicinity. Having one’s photo taken was a rare event, so participants struck deliberate poses. The dapper gentleman with the bowler hat in the foreground is likely Frederick E. Hobbs, the shops foreman.

The tall man in the back row to the right wears a blacksmith’s leather apron, identifying his trade. Can you spot other trades represented here? —Glenbow Museum photo NA-2216-4.

* * * * *

After the railway’s completion in 1885, CPR crews running east from Revelstoke would stop at Donald before picking up another train for the return west. Today, those same crews continue past Donald to Field, deep in the Rockies. This shift underscores the challenges of railway operations in the late 19th century. Back then, crews could manage only 79 miles (127 kilometres) in a day, labouring over steep grades, precarious track conditions, and with regular stops to refuel their steam engines with wood or coal, plus water.

The white building on the left is the Selkirk Hotel, one of Donald’s key establishments during its heyday. To its right stands Forrest House, another hotel serving the bustling railway town. Photo by Bailey Bros., circa 1891. —City of Vancouver Archives #Out P54.2.

* * * * *

In its heyday, Donald was home to 500 residents. While many lived in CPR housing, the town also supported mining and lumbering. Substantial buildings, including a station, locomotive roundhouse, school, courthouse, three churches, four hotels, and significant residences, made up this lively community.

The cemetery, located on the edge of town along the railway tracks and overlooking the Columbia River, was as serene a spot as one might find in those days, with the forest still encroaching on the settlement. A great-uncle of mine operated a sawmill here at the start of World War II but was defeated by the heavy snow and, ultimately, his untimely death. Today, little remains of his operations—or of the town site itself.

IN LOVING MEMORY OF THE INFANT SON OF SIMON AND LORRIE FRASER DIED DEC. 11TH, 1895 SUFFER LITTLE CHILDREN TO COME UNTO ME

* * * * *

Years ago, the Golden Historical Society took on the cemetery as a project, clearing trails and installing a large sign detailing the names of those buried here. Even then, trees were reclaiming the site, and today it has nearly returned to nature. Among the native flora, one can find lily-of-the-valley—a fragrant white flower with symbolic roots in the Victorian era. Introduced intentionally, it was meant to signal the Second Coming and a symbol of hope for a better world.

For the grieving, it provided comfort—a gentle reminder of life’s enduring connection to eternity.

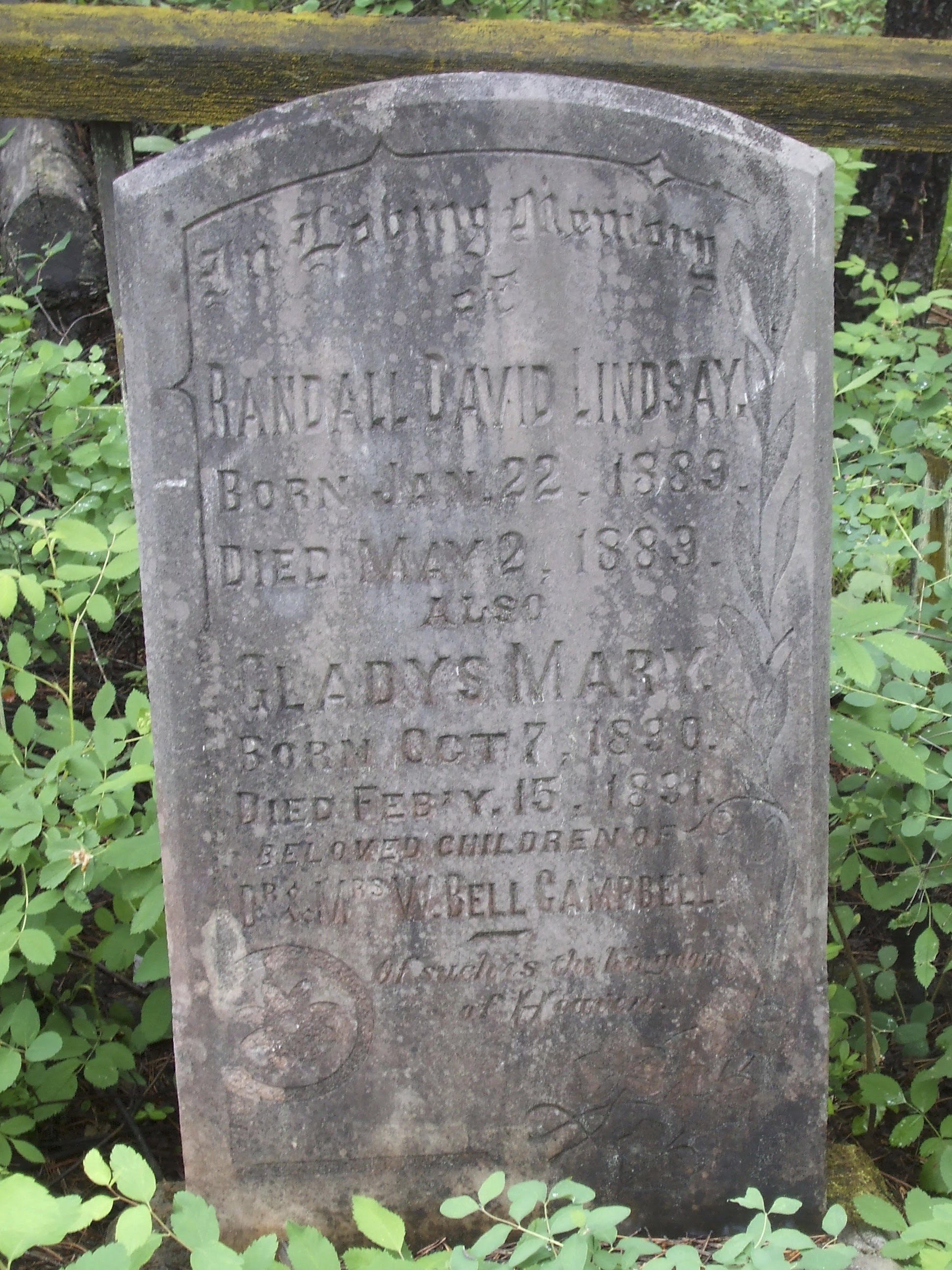

In Loving Memory of RANDALL DAVID LINDSAY BORN Jan. 22, 1889. DIED May 2, 1889.

ALSO… GLADYS MARY. BORN Oct. 7, 1890. DIED Feb 15, 1891. Beloved children of Dr. & Mrs. W. BELL CAMPBELL Of such is the Kingdom of Heaven.

Tragically, even the children of doctors were not immune to the ravages of disease in the days before antibiotics. —Photo ©TW Parkin

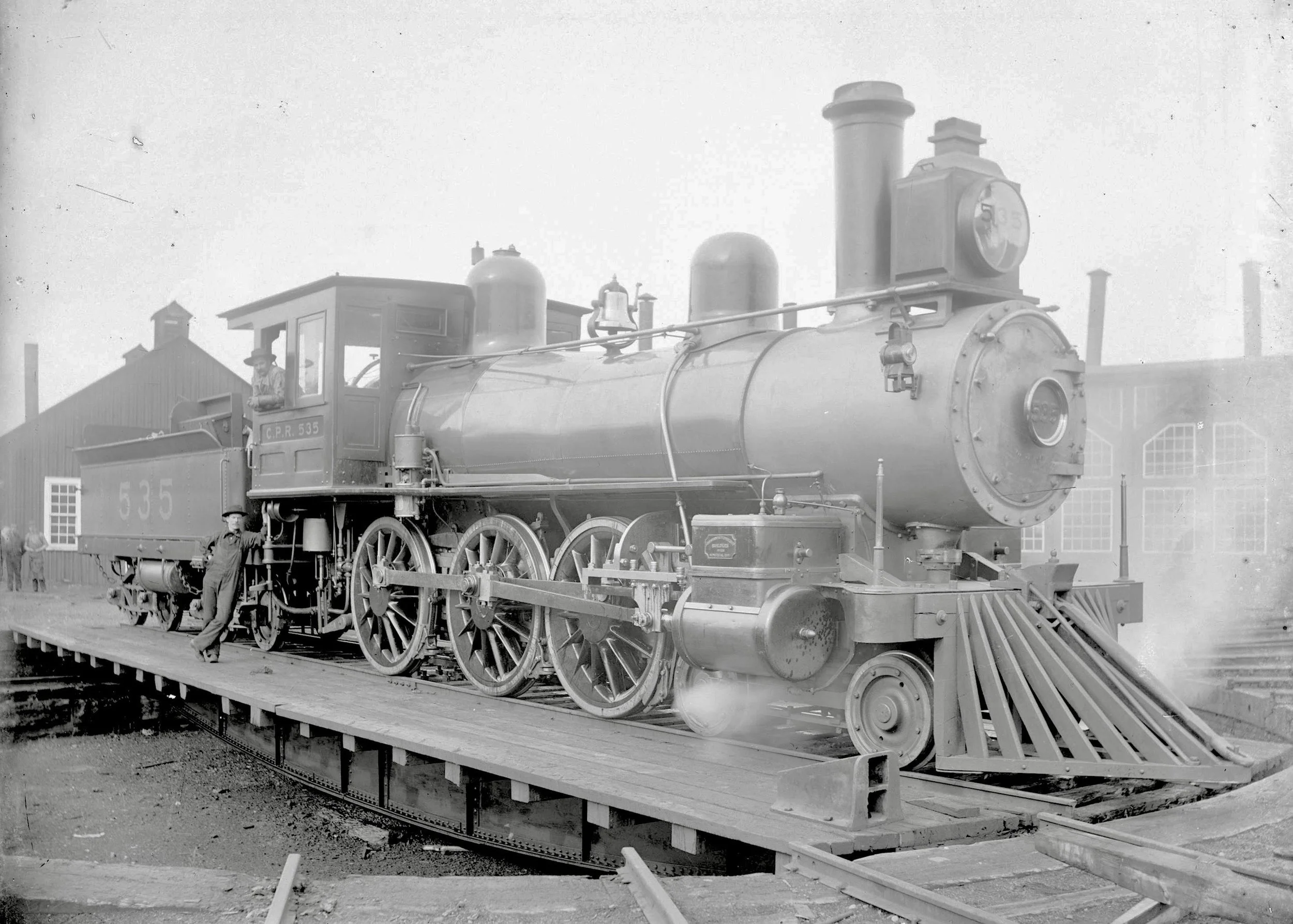

This standard road engine ran between Canmore, Alberta, and Donald, B.C., where it appears here on the turntable. Note the metal receptacle into which the tapered timber lying nearby was inserted. This was for turning the table by “the Armstrong method". The “cowcatcher” (properly called a pilot), is also made of wood. Photo by Norman Caple, circa 1891. —Vancouver City Archives #LGN 652

In 1899, the CPR closed its Donald operations and moved everyone, including personal homes, the courthouse, and two churches, wherever people needed them. It was at this time that the famous incident of the “stolen church” occurred; but that’s another story which Tom might tell you about. (Indeed I will, in next week’s Chronicle.—TW.)

Most CPR employees ended up in Field and Revelstoke. The town was at its lowest ebb at this time. Let’s now look at a few of its former inhabitants:

Revelstoke Herald 23 March 1898

A prospector named Corrigan, of Donald, was found dead in his cabin on Bold Mountain on Tuesday. It seems that he went out some time ago to a claim which he owns on the mountain. The trip seems to have exhausted him, for he had evidently just got inside his shack, shut the door and dropped dead while in the act of taking off his clothes and going to bed. He had been dead a long time. Volunteers were called for at Donald yesterday to bring the body into that town. He was 60 years of age.

Revelstoke Herald 6 April 1898

Residents of Donald deny in toto that there was any unseemliness about the burial of the old man Corrigan, who was found dead in his shack at Bald Mountain. From the posture into which the body was frozen it was impossible to put it into an ordinary coffin, so one was made for him of the best cedar in town and the funeral service was conducted with all reverence by the Donald school teacher.

Corrigan’s burial is recorded at Donald, but no trace of his grave remains—perhaps he was too poor to afford a marker. After the CPR moved its operations to Revelstoke, some older and displaced men found refuge in the remnants of the town, living frugally and often in isolation. A railway acquaintance of mine once visited an old squatter in his shack during the mid-1950s. Curious about the contents of a pot boiling on a battered tin stove, he lifted the lid—then quickly slapped it back.

Supper was two gophers, fur still on, simmering away!

Not all stories of Donald are so sombre. Personalities were larger-than-life in those days, and several CPR men have had their names immortalized—not in the cemetery, but across the landscape. Sheriff Stephen Redgrave ensured order in a bustling railway town—to the extent he put his own son, a constable, in the clink for murder.

CPR superintendent Richard Marpole had a Vancouver neighbourhood named for him, and CPR civil engineer John Griffith must have been well-liked by the local editor:

The Truth, Donald 20 October 1888

The boys tell this one on J.E. Griffith, engineer-in-chief of this division of the Canadian Pacific. A pressing engagement called him east last week. The evening of the second day he ate a hearty supper, partaking liberally of Welsh rarebit, a favourite dish. At the usual hour he retired to his berth in the sleeper, and was dreaming of levels, cross sections, tangents, glance cribs and 4 1/2 percent grades.

Just as he struck the latter subject, he imagined the train was climbing the Big Hill, that the train had parted, and the sleeper was taking the back track down the western slope of the Rockies at a rate of a mile a second. He jumped out of his berth, made for the rear platform, and set the brake so tight that it almost stopped the train.

While twisting the brake he awoke, only to find the night wind flirting with his shirttail, and the train moving slowly over a dead-level Manitoba prairie.

Although a sign on Highway #1 (west side of the Columbia River bridge) marks the turnoff to the Donald cemetery, it’s not a tourist attraction. Next time you pass by, take an hour to peek into Donald. There, you’ll find a poignant reminder of the railway’s impact on western Canada.

Whether educating children about our shared history or simply reflecting on the lives of those who came before, you may leave with a deeper appreciation for the society we enjoy today—and for the people who built it.

* * * * *

About the author

Tom W. Parkin focuses on uncovering stories about western Canada’s road and rail history. He has articles in current issues of Canadian Rail and Branchline magazines. Readers are invited to read others on his website: https://tomwparkin.com/publications.