Forgotten Heroes

So soon we forget; it’s almost part of the Canadian character, it seems.

How many times have I encountered cases of true heroism, often to the point of supreme sacrifice, during my extensive historical research. But even war heroes come and go in memory; civilian heroes rising to the call at home and in peacetime rarely rate more than a momentary ripple.

Monuments? Hardly. Immortalized in school textbooks? Not a chance.

Maybe a street or a building named after them before they fade into oblivion, but seldom more than that.

This week, I introduce you to four men who had at least three things in common: they were professional miners, they willingly risked their lives for their workmates, and they’ve been forgotten.

* * * * *

As it happened, two of our heroes died in Nanaimo’s No. 1 Esplanade Mine, Vancouver Island’s longest producing coal mine, the Island’s largest producing coal mine, and the site of the worst colliery disaster in B.C. history.

Nanaimo’s No. 1 Mine killed more men that any other B.C. coal mine. —Author’s Collection

First up, chronologically, is Sam Hudson. Don’t bother Googling him by name; even when you attach “Nanaimo, B.C. coal miner,” you get just generalized links to the city’s coal mines. Sam’s there—a single reference to the calamitous 1887 explosion that killed 150 men. Actually, 149 men died in the two blasts that rocked the No. 1 during the dinner hour of Tuesday, May 3, 1887.

Sam Hudson, the 150th casualty, gave his life while trying to save them.

A Wellington miner, 46-year-old Sam and his workmates rushed to the No. 1 when they heard the news to offer their assistance. Incredibly, with smoke pouring from the mine, with the threat of fire, further explosions, and gas—without breathing apparatus, not yet invented—Sam took the lead in heading underground, only to be overcome with after-damp, the carbon monoxide that’s the after-effect of a coal fire.

He left a widow and four children. At least, his heroism was honoured by his mates who subscribed towards the erection of an expensive headstone in the Nanaimo Cemetery. It’s still there, but you have to look for it.

* * * * *

If we were to measure a human life by wealth, fame, or by the esteem of those other than a person’s family, social and professional circle, Nanaimo’s William McGregor was a giant.

The manager of the New Vancouver Coal Co.’s No. 1 Esplanade Mine, his funeral procession was a mile long–the largest in the city’s history up until that time. He was just 43 when he died of injuries sustained underground, in November 1898.

When the afternoon shift failed to contain an ignition of gas in Lamb’s Incline on the main level of the No. 1, McGregor, fire bosses James Price and George Lee, timbermen Peter Hygh and Donald Ferguson, and miners Fred Hurst, E. Edmunds and H. Sheppard, took charge.

As they worked, a second blast of open flame seared their faces and hands. Lee was thrown against a wall, his leg broken. As his comrades, in agony from their own injuries, attempted to carry him out, they were overtaken by after-damp and had to abandon Lee to flee for their own lives.

McGregor, first to reach the surface, ignored his own injuries and, we can assume, suffering from excruciating pain, headed back down with fire boss Robert Adam and miner William Thorpe. By the time they found Lee he was unconscious and had to be carried to the foot of the main shaft. Once topside, Sheppard, Hurst and Edmunds were rushed to the hospital, McGregor, Price, Ferguson, Lee and Hygh being taken to their respective homes.

All but Lee were expected to recover in a month to six weeks, according to colliery surgeon Dr. R.E. McKechnie.

But the tragedy didn’t end there.

Next morning, when fire boss Morgan Harris was inspecting the damage, a third blast hurled him against the coal face, burned him and left him in a “weakened condition”. Three days later, George Lee died. The 50-year-old from Coventry, England who’d worked in the mines for 17 years left a wife and three children.

The next day, William McGregor also succumbed to his injuries. The Free Press expressed the universal grief felt by citizens: “Each one individually felt that they were on the eve of parting with a personal friend and that Nanaimo was about [to lose] one of her foremost and most highly esteemed citizens.”

Victoria-born McGregor had begun his career in the collieries as a ‘trapper,’ or ‘door boy,’ then worked his way up until he was appointed manager in 1884. It was said that he “most conscientiously devoted practically all his time and energies to the duties of his important position,” as well as serving as chairman of the school board. As manager of the largest, most productive coal mine on the Island, he “never spared himself, but was always foremost in every needed operation, no matter what the personal risk”.

Just as he had so clearly demonstrated by ignoring his own critical injuries to go back underground to rescue George Lee. What irony that he and Lee were the only two to be mortally injured.

* * * * *

William McGregor wasn’t the only manager to answer the call when disaster struck.

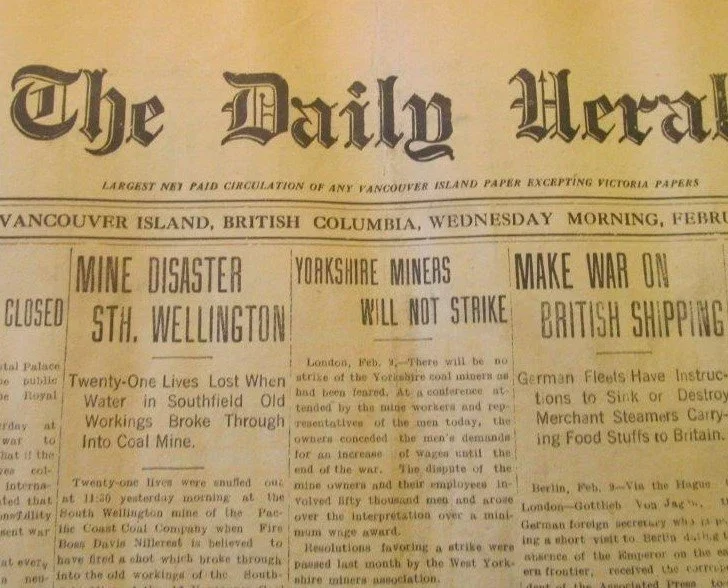

I’ve told the story of the Pacific Coast Coal Mine disaster of Feb. 9, 1915 (Doomed Miners’ Day in Court) when fire boss David Nellist fired a shot that broke through into the abandoned Southfield Mine and “the inrushing waters drowned all the men in the section of the mine affected...”

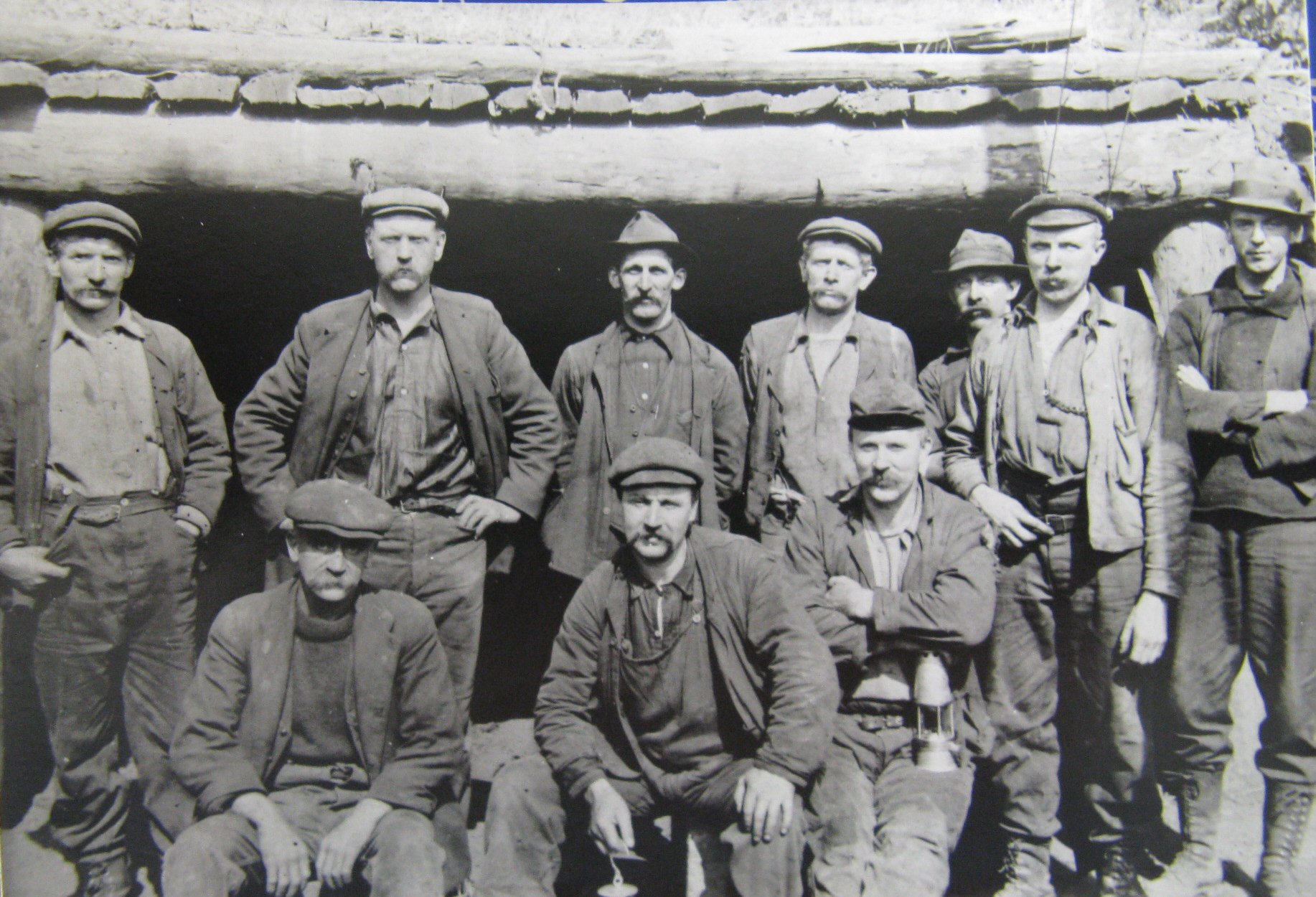

Miners pose before the entrance to the PCC Mine, South Wellington. —Courtesy Helen Tilley

Only one man, W. Murdoch, was initially reported to have reached safety after a terrifying struggle in the darkness. Among the dead were Joseph Foy, mine manager, and fire boss Nellist who detonated the fatal charge.

It’s Joseph Foy, I’m writing about today. He’d been on the surface minutes before the break-through, but, “upon hearing of the old workings being tapped,” he rushed below to order the men out.

When he opened a trap door to the old stope, a wall of water smashed him against the timbers.

Foy was 48, with a wife and eight children.

Two other heroes that day were Thomas Watson of Chase River, and William Anderson, who were working with the first shift when tragedy struck. Both men had reached a place of safety but chose to go back in search of their comrades.

These men’s actions defy our imaginations.

To deliberately enter the pitch darkness of a mine that’s on fire, with the imminent threats of cave-in, explosion and gas, or knowing that the mine is filling with water so violently that it’s smashing timbers and sweeping before it heavy coal cars like toys...

Why would they even think to do such a thing? Because fellow miners—their workmates and comrades—were in need, and would do the same for them.

* * * * *

Sam Hudson, William McGregor, Joseph Foy, Thomas Watson, William Anderson. How many other acts of selflessness have never been recorded, let alone remembered?

Which brings us to another unsung martyr, Frederick Dunn Alderson.

His place of birth reads like a street directory: Sunderland Bridge, Durham Unitary Authority, County Durham, England. That’s where he was born in October 1874; he was 36 at the time of his death in Bellevue, Edmonton, Alberta in December 1910. A professional miner, he’d left his wife and four children to work in South Africa, India and Mexico before coming to the Nicola region of B.C. and joining the Hosmer mine-rescue team.

Fred Alderson, right, with fellow members of his mine-rescue team wearing their Draeger pulmotor breathing apparatus. —Fernie Museum

He was working as a fireboss in the Hosmer Mine when it became known that an explosion had ripped the West Canadian Collieries Mine at Bellevue, just over the Alberta border, trapping 47 men. Alderson, holder of a B.C. First-Class Certificate of Competency in mine rescue, was one of the first to volunteer his skills.

B.C. was a leader in the use of mine-rescue apparatus known as Draeger Breathing Apparatus at that time.

The Draeger Pulmotor was introduced in Germany on 1907 and helped to save many a B.C. coal miner’s life by allowing rescuers to back-pack their air supply into a mine to reach miners who were trapped by spreading toxic gases. —https://www.woodlibrarymuseum.org/museum/draeger-pulmotor/

To quote the Dept. of Mines Annual Report, “it fell to the lot of our inspectors, managers, and volunteers to render our first aid of this kind to a neighbouring Province, and it is to be regretted that in this noble attempt to save the lives of their fellow-men, one noble life was sacrificed from among the rescuers...”

James Ashworth, “Esq., H.E.,” general manager of the operating department of the Crow’s Neat Pass Coal Co., who directed one of the rescue parties without the aid of oxygen helmets, described the hellish situation that faced the rescuers who included Fred Alderson.

He and Mines Insp. Robert Strachan were the first to enter the mine, both wearing Draeger pulmotor which consisted of a helmet attached to air cylinders (each backpack weighed 30 pounds) that gave them two hours’ oxygen supply. But they’d only gone about 600 feet when Alderson said there was something wrong with his helmet. It isn’t stated whether he repaired it or if he exchanged the helmet, as they carried on and found a group of men clustered around a compressed-air pipe at No. 124 chute.

As Ashworth explained, the problem then was how to bring these men back to another compressed-air outlet at No. 84 Chute, 2000 feet distant through toxic air.

“It was agreed that Strachan should go out and take one man with him by the aid of Alderson’s Draeger outfit, and thus Alderson was left inside with the men without any rescue apparatus. Mr. Strachan then started in again with his two-hour apparatus and carried another complete apparatus for Alderson. Alderson then put on the apparatus, and Strachan stripped off his own and put it on another man, whom Mr. Alderson then took out to No. 84.

“Alderson again started in in his outfit, and carrying another full suit for Mr. Strachan’s use; the load, however, was too much for him, and he dropped it on the way. On reaching Mr. Strachan he had his chin-valve open, and said he thought his potash cartridge was played out, and consequently he was himself very exhausted. He then took off his apparatus and remained inside with the men to be rescued, and who were still in good form, having the high-pressure air to keep them alive.”

Strachan donned the helmet Alderson had dropped, which operated correctly.

By this time, Draegermen Birmingham, Matusky, Evans and Huby had arrived with two sets each of apparatus with half-hour and two-hour oxygen cylinders, and potash cartridges. Matusky, the first to reached the survivors, was alarmed to find everyone in a state of collapse.

“One man, the firehoss, was standing, and was just able to speak, but was incapable of assisting Matusky in putting the half-hour apparatus on him. Matusky then left the half-hour apparatus with the man, and hastened out to report the serious state of affairs. A messenger was then dispatched...to bring in additional help, and a conference was held to determine what should be done to save the men at No. 124 chute.

“It was decided to make a dash and pull out the men without waiting for the extra oxygen or for a rope, which had also been sent for. This ‘forlorn hope ’ party then formed themselves into a string of about 10 feet apart. Mr. [Strachan] led the way, and carefully tested the air as he advanced, [detecting deadly firedamp with his safety lamp] before he reached the unconscious men.

Picture it: 21 survivors, a weakened Alderson, and their would-be rescuers, with only eight sets of breathing apparatus between them, having to, as Ashworth put it, sauve qui peut (run for their lives) a distance of 2000 feet in air thick with methane and carbon monoxide.

There was no real running, of course; rather, they shuffled and stumbled along like drunks, with only their headlights and a few hand-held safety lamps to light their way. All the while, trying not to breathe the toxic gases by taking turns with the resusitators. There was no pain, just a growinging weariness that made a man want to sit or lie down and go to sleep. Some of the men had to be goaded onward.

As the song says, it as dark as a dungeon down in the mine. This 1908 shot of a miner at work in the Extension Mine was illuminated by the photographer’s flash. —BC Archives

When one rescuer went ahead to alert those waiting at the entrance of the situation, a Dr. McKenzie, eager to help, grabbed a pulmotor but only made it partway before he, too, collapsed and had to be helped back to the entrance with the help of a rope towline. Somehow, rescuers and rescued made it to where all could be revived by artificial respiration.

All but one miner and Fred Alderson who, when found, were lying side by side in death, Alderson having shared his breathing helmet with the other man until both succumbed to gas.

In reconstructing events afterwards, it was thought that Alderson, in his haste to reach the survivors, had overtaxed his breathing apparatus by over exerting himself and inhaling more oxygen than it was capable of supplying. When he removed then replaced his helmet, he’d inhaled foul air and, in effect, poisoned his air system. It was suggested that an auxiliary cylinder of compressed air be attached to the apparatus to allow for future contingencies.

* * * * *

The lost Bellevue miners left 21 widows and 42 children.

The Bellevue, Alberta Underground Mine Museum honours its “black past.” —Wikipedia

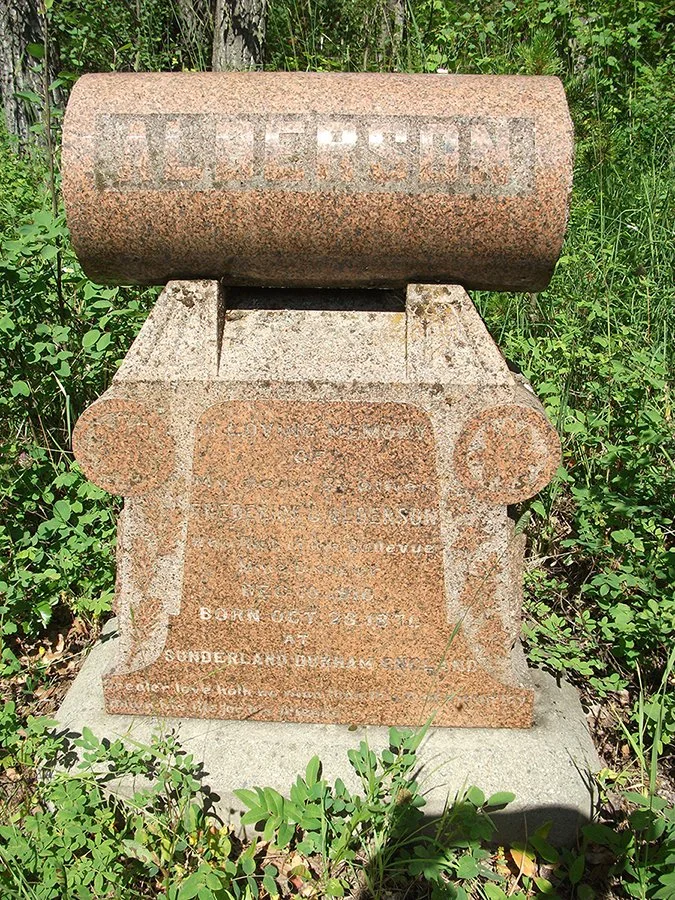

As for Fred Alderson, it’s said that fellow miners, the public and the B.C. and Alberta governments contributed substantially to his family who were still in England, never having made it to Canada. Fred was returned to Hosmer for burial where his pink marble headstone bears the slightly edited inscription that has adorned cenotaphs and military monuments since the First World War: ‘Greater love hath no man than this—that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

Fred Alderson’s handsome pink granite headstone in the Hosmer, B.C. cemetery.—www.findagrave.ca

Unlike the other martyrs mentioned here, you can find references to the “Hosmer Hero” on the internet; sites such as Find A Grave and When Coal Was King. In 2016, Fernie historian and coal miner John Kinnear proposed that Fred Alderson be awarded a posthumous Medal for Bravery by the Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum.

I’m not aware that anything came of Mr. Kinnear’s suggestion.