From the Pen of ‘J.N.T.’

I’ve always been drawn to autobiographies—life stories spoken from the horse’s mouth, so to speak.

Yes, one can question their objectivity. But how many people keep diaries or journals with distortion or deception in mind?

This is what makes personal reminiscences—historic events witnessed or experienced firsthand, invaluable. No one—I say this as one who’s written 1000s of biographical texts—can tell us what it was really like better than someone who was there, someone who didn’t just observe, but who actively participated.

Someone who has walked the talk.

Someone like James Nealon Thain, mariner, businessman and adventurer, the subject of this, the first BC Chronicle for 2024.

* * * * *

Almost a century has passed since the initials ‘J.N.T.’ last graced the pages of the Victoria Colonist. It was back in the winter of 1881 that James Nealon Thain, popular Victoria businessman and member of an illustrious pioneer family, was “struck by paralysis of the brain” and died in hospital the same day.

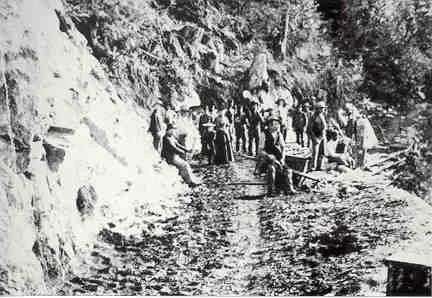

Unidentified members of a CPR survey team. Thain’s crew was but one of many during the laying out of a transcontinental railway route. —Wikipedia

With his death Colonist readers lost an amateur journalist whose columns, based upon a diary he’d kept as a member of a CPR survey party, had provided a fascinating look at the “great Chilicooten country” of interior British Columbia.

“My egotism,” the modest Thain had chosen as the title for his series in 1874, when he first begged the indulgence of Colonist readers with his reminiscences of the previous summer. Excerpts from his diary, he hoped, “may afford a few minutes’ entertainment to many who still very likely seek British Columbia for a livelihood".

One of the purposes of his taking up pen and paper, he explained, was to enlighten newcomers to the province as to the real conditions prevailing in the Interior: “Every person who leaves Fort Yale for the interior of B.C. expects to see wide-spreading fields of rain, and meadows of Timothy bursting upon his vision at every turn of the road; but such expectations are a disappointment; in fact, a vanity.”

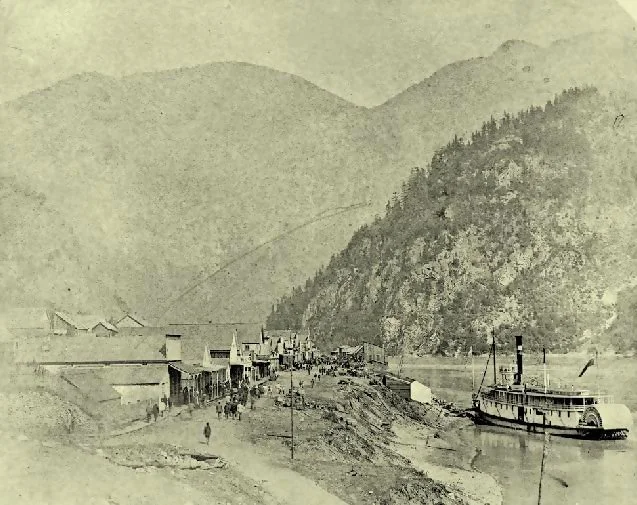

Yale, B.C. during construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. —Wikipedia

What the newcomer could expect to see was the famous Cariboo wagon road, winding its way through mountain and vale, high above the Fraser: a “stupendous causeway” which he termed a monument to the Royal Engineers whose skill and dedication had made the highway an historic reality.

“You are at times,” Thain marvelled, "apparently locked in deep gorges, where the mountain tops on the opposite side of the river tower thousands of feet above your head, covered with perpetual snow; and again you’re soaring over their side with perfect ease at the rate of four or five miles an hour [by stagecoach], and occasional straight stretches will give you a sight of the Fraser or Thompson River for miles....”

A six-horse stagecoach near Ashcroft. James Thain and fellow passengers had to get out and walk when they came to steeper hills. —BC Archives

Charging along at full gallop, the four-horse, six-passenger coach followed a torturous pockmarked, 18-ft-wide roadway, slowing only for the steeper climbs, when passengers were asked to dismount and make the grade on foot; a periodic interruption which allowed them to exercise their sore muscles. Once over the hump, all would again embark for the descent, made at a “famous” pace, around hairpin curves.

“Every turn of the road presents a different picture and every few miles changes the character of the foliage of the trees along the lower parts of the road; but no change is visible in the upper parts, as you have ever before your eyes the spruce, fir and pine to look at and wonder from what source they obtain their sustenance (they surely do not subsist by breathing).

“Mighty roots are clasping solitary boulders with their huge claws, and penetrating far down into the crevices of the rocks seeking for mould and water, while their enormous bodies stretch their heads heavenward, 200 or 300 feet, blooming in gorgeous green, and oozing out [resinous] gums which fill the air with their healthful odours. The juniper, the maple and the cedar help to fill the measure of this scented atmosphere.”

For 451 winding, bumping miles, the Cariboo Road provided a panorama of rugged beauty virtually untouched by man.

Where small clearings the size of town lots in Victoria had been permitted by nature, roadhouses were built. Here, the express company took advantage of the naturally fertile soil by planting a rich assortment of vegetables and fruits. Deeper into the valleys, the first farmers had made their own clearings in the jungle-thick forest, with equally favourable results.

Such was the majesty of the B.C. Interior and, enthusiastic introduction aside, Thain turned to his brief career as a member of a CPR survey crew.

On Monday, July 6, 1874, he’d reported in Victoria to Dr. Trimble at noon for a medical, and, upon Trimble's nod of approval, he was held to be ready to leave town the next day. The following morning, he boarded the steamship Enterprise and sailed for New Westminster, noting, after an absence of several years, that the Royal City appeared to be “much improved,” although partly abandoned.

To reach Fort Yale, Thain took a riverboat such as the S.S. Charlotte, shown here at Quesnel. Note the firewood stacked on her foredeck. —Wikipedia

Boarding the riverboat Onward, he sailed upriver for Fort Yale, to express disappointment at the absence of “improvement,” in the form of civilization along the Fraser’s banks, other than a straggling collection of Native shanties. Even a Catholic mission and its cluster of homes brought scant praise, Thain merely allowing that it was better than its neighbours.

Chilliwack, Langley and Sumas, he conceded, had “a few respectable habitations in sight”. The value of all buildings between New Westminster and Fort Hope, he thought, couldn’t be worth more than $20,000. Fortunately for the retired businessman, the landing at Popham provided some excitement when the Onward disembarked a cargo of Chinese labourers.

The exotic scene of coolies in straw hats labouring under the weight of the poles over their shoulders, contrasted with the wide-eyed amazement of an ancient couple who viewed the proceedings from a tall platform set atop four cedar poles on the river bank, and served to draw Thain’s attention from the dismal architectural showing of Fraser River inhabitants.

Upon arrival at Yale in the evening of July 9th, he enjoyed a night of rest, undisturbed by the steamer’s machinery as Yale was her final stop before heading back downriver. Up at 4:00, “Mr. Hunter, the leader of our party on the alert,” Thain and companions left Yale aboard the stage 10 minutes after the Onward slipped her berth for New Westminster.

By evening, after an enjoyable day, the stage pulled into Lytton, some 60 miles “upcountry " of Yale.

Up even earlier the next morning, they left Lytton at 3:00, arriving at Cook’s Ferry by 8:00. So far, the ride by stage had been pleasant, “altho here and there upon the ridges of the mountains, a feeling of insecurity was felt; especially upon Jackass Mountain."

Despite the efforts of road crews, the route was marred by potholes, rotten cribbing and washouts, making the way hazardous. As usual, steep hills meant a stiff walk, the 200-pound, middle-aged Thain complaining that he felt the exertion more than his fellow passengers “as I am so soft”.

A road crew at work on the historic Cariboo Wagon Road. By 1874, the lifeline to the B.C. Interior was in sad shape. —www.pinterest.com

There were further signs of the state of depression in which British Columbia, indeed the entire Pacific Northwest, found itself in, in 1874. Besides the poor state of the roads, he noted that many of the bustling mining camps of 10 years before were virtually abandoned.

In 1863, 100s of miners and large mule trains were to be met on the roads; in 1874, just a few Natives and Chinese passersby, and 40-odd pack mules.

High above the Thompson, where the road skirted the cliffside, Thain recognized the spot where, in 1863, his horse slipped to its death; this, before completion of the road. By 8:30 p.m., July 11th, the crowded coach wheeled into Clinton, 138 miles from Yale, in 104° F heat, and, after a few hours rest, resumed their bone-jarring, defying journey.

Bridge creek, Lac la Hache and 150-Mile Post were passed in due course, the seven members of Mr. Thain’s party wedged into the seats and watching helplessly as the driver, who was “very expert, very cool and quite a gentleman,” surmounted every obstacle and virtually defied gravity as he guided his team within inches of the mountain’s edge.

On Wednesday, July 15th, the surveyors met their pack train which included none other than “Uncle” Billy Barker of Barkerville fame, who, Thain said, “afforded much amusement to everybody in his merry situation”.

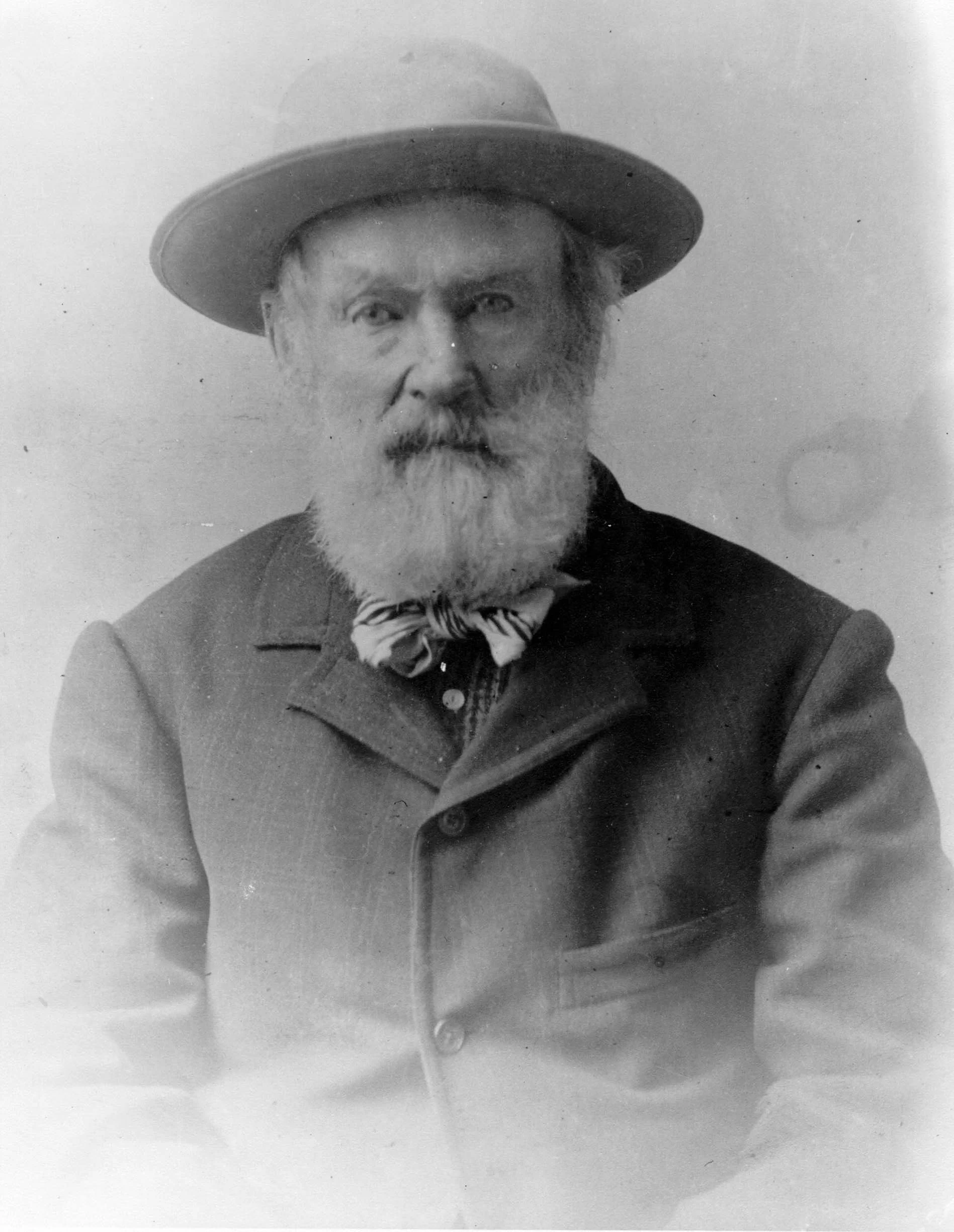

The legendary Billy Barker whose rich gold strike created Barkerville. Like many others, rich and poor, he died penniless. — www.barkerville.ca

The following day, they set up camp at the head of Williams Lake, the trout fishing being reported as very good. On the 17th, the actual survey work was begun in heavy rain, Thain smashing the crystal of his watch while crossing a creek.

Fording the stream became an uncomfortable routine necessitated by the fact that their work was on one side of the river, their camp on the other. Why this was so, considering that navigation usually took considerable time and effort, Thain didn’t explain. On Sunday, he didn’t care, having the day off to do his laundry and to write letters.

Daily shifts usually were 12 hours long, according to Thain’s diary, the work being described as “heavy”. Daily progress was noted in chains. On Tuesday, July 21st, he wrote: "at the chains all day". Thursday, they “chained up to 372 chains," the crew having covered 250 miles from the head of Williams Lake to the Fraser River. On Friday, despite heavy rain which almost ruined their breakfast and made life uncomfortable, the crew surveyed 461 chains.

On Saturday, Thain and his assistant had to complete their section over a 400-foot precipice—“rather ticklish work” for Thain and near-disastrous for his companion, who narrowly avoided a rockslide.

But, with Sunday, he enjoyed a peaceful day with his laundry as most of those in camp passed the day by panning for gold. On Monday morning, it was back to work, moving the camp across the river into ‘Chillicoaten country”.

On Tuesday, July 28th, he glumly noted: "My knees are growing very stiff and swollen. I am losing heart; rain with thunder and lightning. We have chained up to 516 chains at 100 feet each, counting from the commencement, not counting the triangular survey of the crossing of the Fraser River, or changes of root consequent upon errors as to the height of grade...”

Despite his low spirits, he wasn’t immune to the splendours of the wild flowers, then in full bloom.

Even when in pain, James Thain noticed the beautiful wild flowers around him. —Encyclopedia of BC

But continuing rain and electrical storms did little for Thain’s morale; neither did his wound, caused by a sharp stick which penetrated his thigh when a log upon which he and others were sitting collapsed. Nevertheless, it was back to work. Fortunately, that Saturday was a holiday, enabling him to rest up. Sunday was spent in moving camp. Monday and Tuesday were spent in camp, Thain taking advantage of the wealth of the lull to life flat and still upon his back due to the tenderness of his injury.

Despite the pain, he managed to complete a mental survey of the area's farming potential, concluding that small farmers with limited capital would have difficulty in making a go of it upon the Fraser's flatlands, although those with backing would be able to build the extensive irrigation systems required.

From his cot, he also observed the wildflowers in bloom, as the other members of the survey returned to camp with the news that they’d have to find another route as they’d encountered 1400-foot high bluffs.

Two more days passed, with 100° heat, as Thain remained in camp. His wound was healing slowly but the heat made him extremely uncomfortable; almost as uncomfortable as the men engaged in rerouting the survey around the bluffs. That Saturday, camp was moved again, Thain making the shift on foot at a cautious pace.

That night, feeling better, he marvelled at the beauty of the star-studded sky.

“The heavens looked like a blaze of glory, the stars shone with the brilliancy of a winter’s night; it was exceedingly beautiful; our camp amid the shade of the tall dark pines while the rippling of the brook over its rocky bottom made music enough to lull one to slumber.”

With Sunday, all remained in camp to launder and mend clothing, Thain writing letters and looking forward to returning to work, “although not well”. On Thursday, he attempted to rejoin the others, only to be ordered back to camp. Much to everyone's surprise, the temperature ranged from a low of 35° at night, with frost, to 80° at noon. despite heavy overcast. Thain had no complaints as he was at last permitted to return to work—only to be ordered back to camp at noon, with the others, because of a thunderstorm.

However despite continuing bad weather, they continue to make progress. One day, their work was made all the harder when the man in charge of the horse has lost his way on the trail, forcing the survey teams to hike all the way back to camp after a long day, Thain not stumbling to his tent until after 10:00, when, after a hot cup of tea, he fell into bed.

But, with Sunday, August 16th, he was able to sleep in, a welcome day of rest as his knees were again swollen and painful.

When the entire camp moved the next day, he attempted to keep up with the main party, but was forced to fall behind. Losing his way, he stumbled about in the tall grass in timber for some time before coming upon the survey line. After resting and eating beside Meldrum’s Creek, he learned that almost all of the others had become lost also, when he said out to rejoin the group. He hadn't hiked two miles when a rider galloped up to order him back to the Meldrum farm house where the men were to reorganize.

Upon reaching the banks of the Fraser, all piled into a barge, so overloading the craft that Thain was terrified they’d capsize in the swift current. "I am fond of dash and energy myself,” he swore, "but I must certainly say that I consider this passage of the Fraser was courting danger for no motive whatever...”

After a very close call, the crowded barge reached shore safely with its relieved cargo.

With this, Thain gratefully severed his connection with the survey. Throughout, he’d carefully observed the country, concluding that, for the most part, it afforded unlimited potential for farming and ranching although prospective settlers would require adequate backing and organization to succeed.

One other matter had attracted his notice: the state of the animals used in the pack trains throughout the Cariboo. Although he couldn't remember ever having heard anyone else comment as to the manner in which the poor beasts were treated, he couldn't overlook the cruelty of most packers.

"To see you their [animals’] chafed bones and miserable hips sticking nearly through their skin is disgusting; and all to reduce the price of sugar 1 cent per lb. or to make a glass of whisky a little stronger...” He expressed the fervent hope that the pack trains’ owners, most of whom remained in the Old Country, would face legal action in Victoria for the abuse meted out to their animals.

As for the fellow members of the survey team—those " high-spirited and gay-hearted young men"—he left their company with regret and gratitude; this despite their one failing—profanity.

Just 7 years after, James Thain was dead at the age of 59, having followed his brother John by two days. Respected as a pioneer businessman of San Francisco and Victoria, and as one of those responsible for the formation of Victoria Fire Department, James also had been involved in the initial navigation of the Fraser River between New Westminster and Fort Yale.

Among James N. Thain’s accomplishments was his role in forming the Victoria Fire Department. —Vicfdbc

Perhaps more than anything else, James Thain had been a remarkable observer and student of Nature, foreseeing the day when a collection of shanties along the Fraser would give birth to modern communities and a booming province.