Golden Bralorne Got Off to a Slow Start

Interest in the Bridge River Valley’s mineral potential dates all the way back to 1865 when a government-sponsored mining exploration party reported having found gold in “that part of the country lying between the Chilcoaten and Bridge Rivers,” specifically on Cadwallader Creek on the South Fork of the Bridge River.

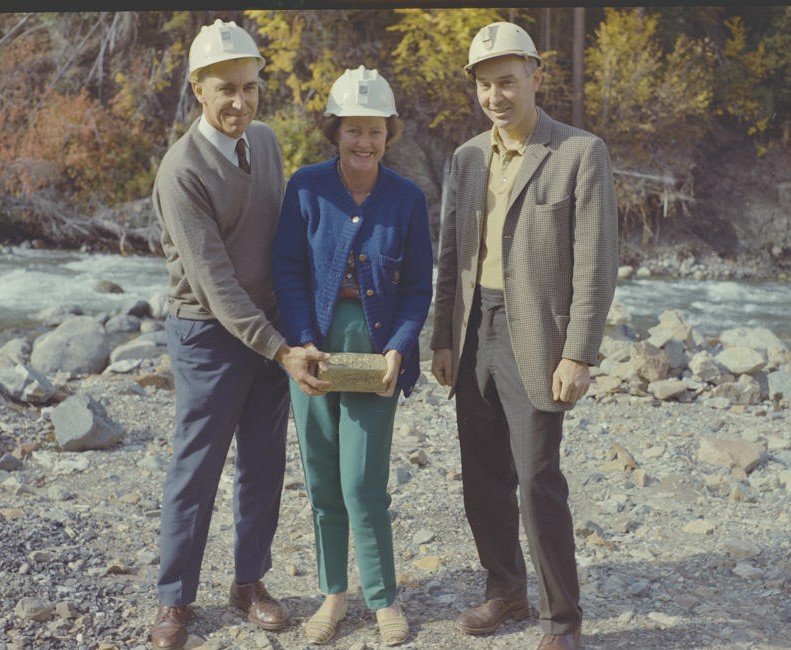

At the time this undated photo was taken, that ingot of Bralorne gold was valued at $30,000. —BC Government photo

They were almost out of supplies by then but, determined to do the job right before turning back, Andrew Jamieson instructed his men to build two sluice-boxes and to “wash as much...dirt as possible in the short time we had at our disposal” while he and Cadwallader examined several other creeks in the immediate vicinity.

They detected colour almost everywhere they tried, as much as $9 from a three-foot layer of gravel. As their crude set-up undoubtedly had allowed more gold to escape, Jamieson was duly impressed.

But three decades were to pass before miners again showed interest in the Bridge River country and what would prove to be one of the richest gold producing areas of British Columbia finally began to come into its own.

How rich, in a province that was founded on gold?

One of the richest in all Canada—four million ounces of gold and one million ounces of silver from eight million tons of ore, according to one source.

Another source puts it this way: “In 1932, Bralorne poured its first gold brick, weighing 393 ounces and valued then at $6,700. In 1943, with ore reserves estimated at over one million tons, averaging over one-half ounce of gold per ton, Bralorne was cited as the greatest lode operation in the world. In 1948 the stock market listed Bralorne’s value at over $10 million.” (Author’s italics.)

How ironic then that it had taken almost 70 years to put the Bralorne and Pioneer mines, on the map.

* * * * *

This 1940s photo shows Bralorne Company execs posing with yet another rich ingot. —BC Archives

The distant Bridge River country was long overshadowed by the more apparent and accessible wealth of the Fraser River and the Cariboo. One of the few who foresaw potential in this neglected region was Harry Atwood who, with a grubstake from Lilloet hotel keeper William Allen, decided to try his luck on all-but-forgotten Cadwallader Creek.

He named his claim the Pioneer after Allen’s hotel, then traded a half-interest with E.H. Kinder for a quartz mill to crush ore. The very term suggests machinery of some consequence and, according to another veteran prospector, A.W.A. Phair, Atwood took it for granted that Kinder’s mill was similar to a 10-stamper he’d seen at Anderson Lake.

He didn’t know that Kinder had ordered it sight unseen from California for $125. Its eventual delivery by freight wagon to Allen’s hotel sparked hilarity among spectators, wrote Edward Norcross, who heard the story from an eyewitness: “The driver threw off package after package but no mill appeared,” while assuring Kinder that it was somewhere in the wagon.

“At last it was reached and, as a bystander observed when the general laughter had subsided, it was just big enough to make a good-sized coffee grinder.”

“It was a mill probably used by an essayer [sic],” thought Phair who was sure that Kinder, despite having a reputation for being a joker, was as surprised as anyone at its diminutive size. Small or no, to work it went, only to prove to be totally inadequate at just 100 pounds of crushed rock per day. In desperation, for half the profits, another deal was made, this one with Arthur Noel to build a water-powered drag-stone mill.

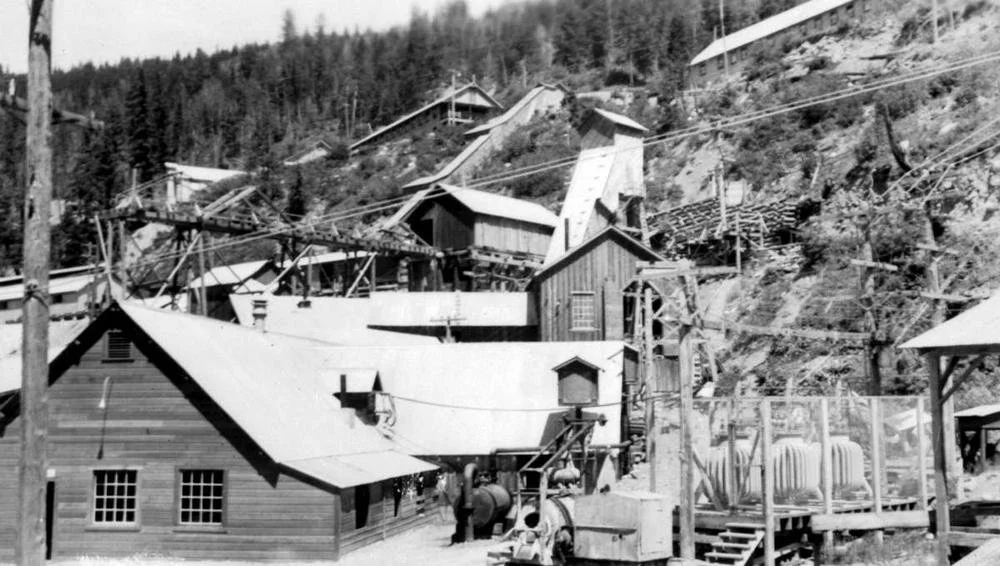

Some of the Bralorne Mine workings in 1937. —BC Archives

Supposedly the first to be used in all of Canada, it worked but was so primitive that it recovered only a fraction of the gold processed. But—that which was captured, was rich enough to allow its operators to make a living of $10 a day. For 10 years, Atwood having dropped out, Kinder and Noel earned every penny they made by packing the ore from the adit to the arrastra on their backs.

Then Kinder was left to work the claim alone for several more years, Noel having forsaken the excruciatingly hard labour for the board room, so to speak. In 1911, for $26,000, he, Peter and Andrew Ferguson, Adolphus Williams and Frank Holten bought the Pioneer property outright.

Four years later, now without Noel and Holten, Pioneer Gold Mines Ltd. was incorporated. Between 1914-17, using an improved mill and power plant, the partners produced $135,000 (you can multiply this by 20 for the current value). and put the mine up for sale. Incredibly, or so it seems today, despite some desultory interest, nothing happened until 1920 when a larger company secured an option for $100,000, only to lose it when they failed to make the final payment.

The musical chairs of proprietorship continued with another sale and new major shareholders, this time a Vancouver syndicate that, after investing a further $50,000 in development, suspended operations within two years. By this time, only the Ferguson brothers and Williams remained of the original syndicate.

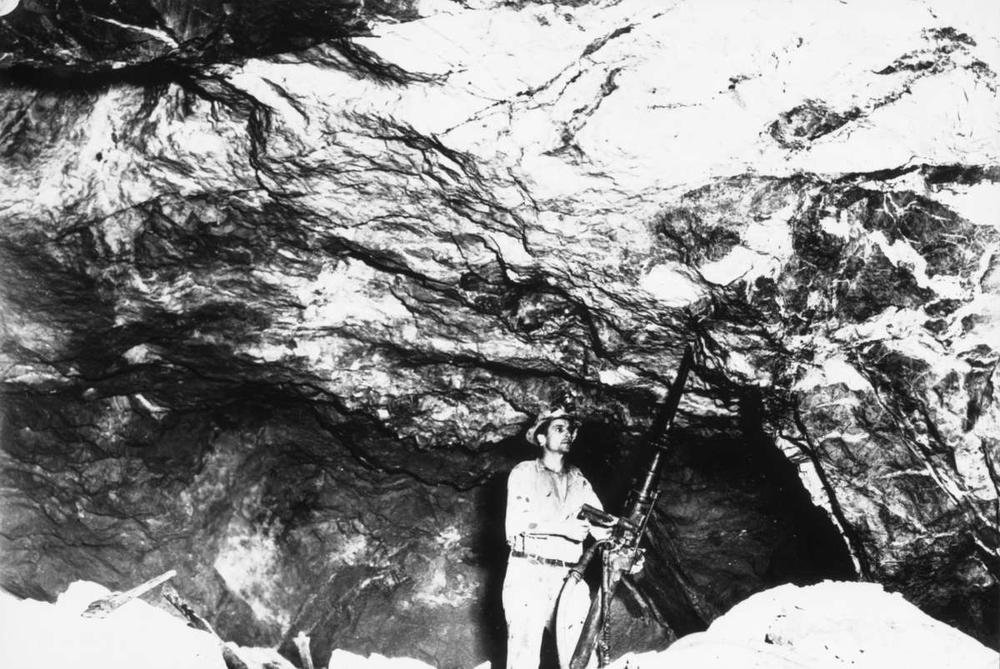

A ‘hard rock’ miner operating his pneumatic drill in the Bralorne Mine. Other than his hard hat he appears to be working without any other safety gear.—BC Archives

None of these bumps fazed mining engineer David M. Sloan who’d been hired to head development. He became so convinced of the Pioneer’s potential that he acquired his employers’ 50 percent option and sold half-interest to J.L. Babe. But the Pioneer’s apparent jinx continued; they were able to raise only $4,000, just enough to resume production on a small scale.

With 1928, Babe was gone, Col. V. Spencer was in—and the mine was finally in business.

The struggle to make a go of the Pioneer had taken a full quarter of a century.

* * * * *

Pouring ingots at Bralorne in 1937. —BC Archives

The rest, as they say, is history. As almost always is the case, however, there’s a remarkable story within the story, this one a tragic legal sideshow.

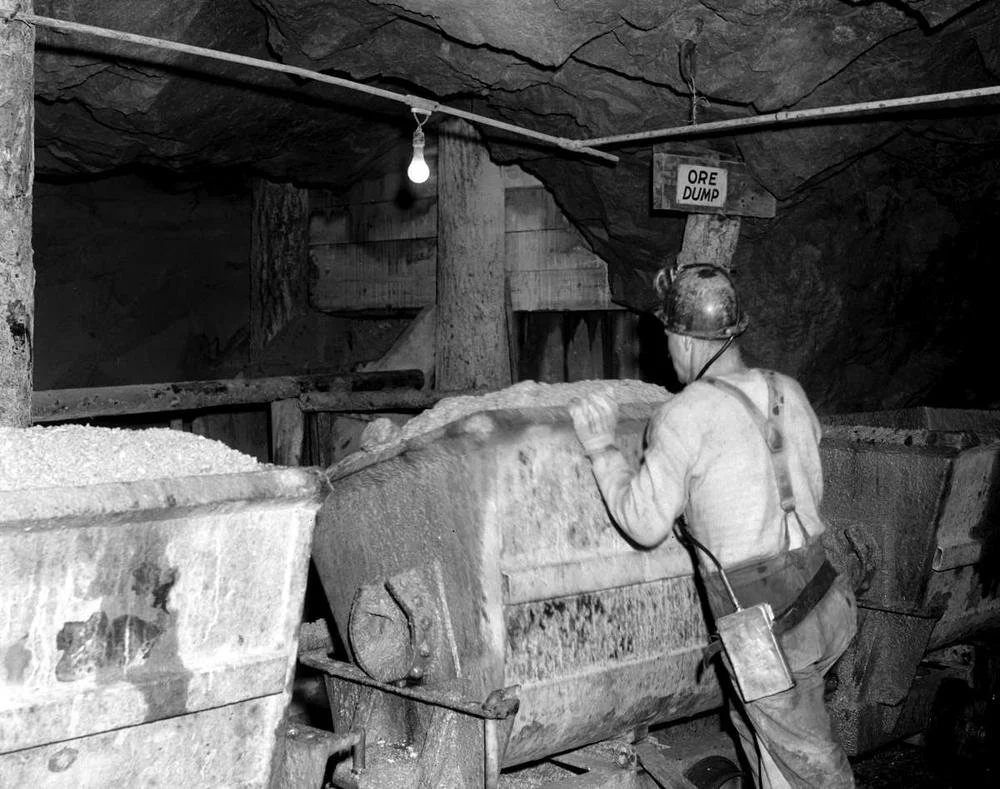

A miner fills an ore car at Bralorne in 1945. —BC Archives

Vancouver business writer Aileen Campbell told the story in some detail in 1975, beginning by reporting that three heritage-style houses on Robson Street were about to be demolished for a residential-commercial complex. Two of the houses, she wrote, had been built at the turn of the century by “long forgotten miner” Andrew Ferguson, once a part-owner of what became the Bralorne-Pioneer Mine, who’d died intestate in 1962.

With his brothers, Ferguson had made money in the Lardeau in southeastern B.C. silver boom, investing some of it in the Robson Street properties and, with partners Noel, Williams and Holten, in the Pioneer Mine in 1911.

They sold controlling interest, 51 percent, in 1924. By the early ‘30s, Andrew was in court, on his own behalf and that of his late brother Peter, suing the then-owners “for fraudulently conspiring to bankrupt” the company so as to not to have to pay them.

Ferguson contended that he’d been promised $50,000 for his share of the $1.5 million sale price. He lost his first suit but successfully appealed to the B.C. Supreme Court. It was a Pyrrhic victory, alas, that court ruling that the defendants were, in fact, guilty of a breach of faith—but faulted Ferguson for not having immediately sued to have the 1924 sale set aside.

After several years of legal wrangling, the Privy Court, the highest court in the Commonwealth, ordered a new trial. By that time, Ferguson had been forced to sell off his real estate holdings and was living in a tiny upstairs apartment in one of the Robson Street houses he’d built. Details of the settlement he finally reached with the Pioneer owners were never publicly disclosed.

A Bralorne miner dumps ore into a “grizzly,” 1945. —BC Archives

According to one of his lawyers who was anonymously quoted in the Vancouver Province, for all of his years of litigation, Ferguson realized little for his troubles and paid dearly on a human scale: “When I knew him during the case, he was a little man, meek and mild. The life had been squeezed out of him. He was not bitter, though there had been a battle, and he hadn’t won it.

“It was the 1924 sale and option to the new company (headed by Vancouver businessmen A.H. Wallbridge and A.E.Bull) that squeezed out the original investors.”

Ferguson became a recluse until his death in 1981, having had to live on his settlement, assuredly modest, with the bitter pill that, in 1934, in the midst of his courtroom battles, the Pioneer—“his” Pioneer—had yielded more than $1 million profit in a single six-month period and was described in a financial report as “the world’s richest mine”. Over nine years (1931-1942), which spanned most of the Great Depression, it paid shareholders $9.3 million in dividends.

* * * * *

Despite all the legalities and travails, Pioneer Townsite, 300 miles north of Vancouver, had come into being with all the amenities of a small city, including a 4,000-square-foot dance hall. In 1948, the stock market listed Bralorne’s value at over $10 million.

Operating the hoist at Bralorne, 1945. —BC Archives

In 1959, the Pioneer and neighbouring Bralorne Mine, composed of the Lorne, Marquis and Golden King claims, were merged as Bralorne Mines Ltd.—just in time for the pioneering Pioneer to be phased out of operation the following year.

In 1971, with gold still pegged at $35 an ounce, Bralorne was shut down and sealed, the company town sites sold for development or for year-round recreation purposes. Attempts were made to resume limited operations the following year, but not even rising gold prices in 1981 were enough to spark re-opening because of new mining royalties imposed by the B.C. government.

That changed with the record-breaking prices of gold in recent years, and it was back in business by 2011. Heralded the Bralorne Gold Mine’s website, “Recent discoveries between the Bralorne and King Mines have opened up significant new mineralization. Phase III development, now underway, is focused on expanding new zones and continuously stockpiling reserves for the 100 [ton per day] gold mill.

“The current Bralorne mill is permitted to operate at a capacity of 500tpd, so this will provide ample room for expansion. Bulk testing is complete and with all permits in place the mine is now gold producing once again.”

In May 2022, the Vancouver Sun noted that Bralorne Mining Camp, which reached as much as 5,000 feet below the surface, had yielded 4.5 million ounces of gold—$4.5 billion U.S.—over the previous 40 years. A combined average of 2,300 ounces per vertical metre mined placed the Bralorne mines among the largest, highest grade and longest producing mines in British Columbia.

* * * * *

My Bralorne file, consisting of newspaper clippings, government reports and reminiscences, is an inch thick. Here’s a random sampling of items and facts, including some from more updated websites. Keep in mind as you read that Bralorne was decades late to the party!

A 1960s shot of a Bralorne gold bar, one of 1000s poured on-site over the mines’ lifespans. —BC Archives

‘Bralorne’ owes its genesis to the combination of the development company, Bralco, that also owned the Lorne Mine as of 1931.

“Bralorne was a wild place in the 40s,” a former resident recalled.

Between 1931-1971, the Bralorne and Pioneer mines employed no fewer than 10,000 miners who, with their families, lived in two town sites with a combined population, at the high point, of 1,000. Both had their own schools, theatre, hospital and recreation facilities. However, the double whammy of higher production costs and gold still being fixed at $35 to the ounce, led to the mines’ closure and residents, far off the beaten track and jobless, began to drift away.

“Picturesque” Bradian, a third company townsite of 20-odd dwellings, was described as “one of the most intact ghost towns left in the province”.

Bought by Chinese owners for $1 million in 2014, it was back on the market within six months after they found themselves stymied by revised immigration laws.

During its 40-year run, the Bralorne and Pioneer mines yielded $145 million and employed 10,000 miners—“muckers, trammers, timbermen, motormen, brakemen, hoistmen, skiptenders, and pipefitters all made their way through the maze of tunnels at Bralorne”.

As early as 1943, Bralorne had paid nearly one-sixth of all dividends earned by all of British Columbia’ s lode mining companies since 1897. Upon closure, only half of its identified veins—one of them almost a third of a mile long—had been worked, after producing “more ounces of gold and silver than any other mining operation in the province”.

For all of the incredible wealth that has been industrially mined to date, amateur prospectors still pan for gold here, as did this man in 1979. —BC Archives

Bralorne area, just south of Gold Bridge, has become popular with outdoors adventurers for its hunting, fishing, prospecting, rock hounding and skiing opportunities. The historic community also has a museum that celebrates its golden past.