Green Gold - Jade

It took well over a century but the hardy Chinese miners who helped to carve a province from wilderness enjoyed the last laugh.

Today, decades later, thousands of recreationists throughout British Columbia are participating in a modern-day boom in their eager search for that once derided ‘green gold,’ jade.

Today’s prospector are called rockhounds but the name of the game is the same—the thrill of the hunt and the pride of achievement that comes from transforming a piece of stone into a beautiful gem.

British Columbia’s pioneer miners from the Orient who shipped unknown tons of the mineral home, often as ship’s ballast, prized jade for its potential in the making of jewellery and works of art; a devotion to beauty which, more than once, earned the derision of white prospectors who measured their own bonanza, gold, in terms of dollars and cents.

Actually, the Chinese prized jade for considerably more than its merits as a gemstone. In fact, Asians generally worship jade for its qualities of a very different nature, the Columbia Encyclopedia explaining, “Jade is prized by the Chinese and Japanese as the most precious of all gems.

“The Chinese in particular are known for the objects of art they carve from it, and they traditionally associate it with five cardinal virtues: charity, modesty, courage, justice and wisdom. Jade has been considered to have great medicinal qualities in the Orient as a general tonic and when swallowed shortly before death [in powder form, I trust], to prevent the decomposition of the body.”

Its very name is derived from the Spanish word for kidney stone, jade at one time being considered a cure for kidney ailments.

Although British Columbians tend to think of jade as being popular only in China, many peoples throughout the world have long prized the attractive stone for its implement-making qualities. As mentioned, the Japanese also cherish the stone, as did ancient cultures in such widely scattered countries as Mexico, Switzerland, France, Greece, Egypt, Asia Minor and New Zealand.

Perhaps it should be pointed out here that the term jade usually applies to not one but two similar minerals. The rarer variety, jadeite, is a sodium aluminum silicate which ranges from dark green to white. The more common, and therefore somewhat less valuable variety, is called nephrite, a calcium magnesium iron silicate which also ranges from dark green to white. This is the ‘jade’ which is found in mainland British Columbia but not on Vancouver Island.

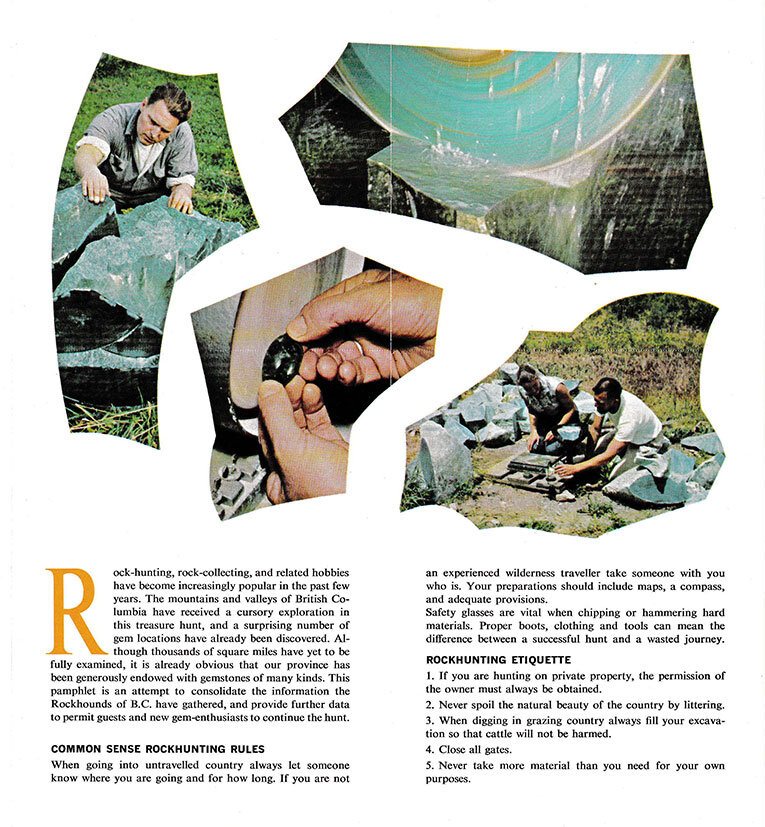

This B.C. Government brochure demonstrates the popularity of rockhounding.

Jadeite is located in Upper Myanmar, Tibet and (before being depleted) in China’s Yunnan province. Nephrite is found in New Zealand, Turkistan, Siberia and Silesia—and British Columbia.

Surprisingly, to again quote the Columbia Encyclopedia, “a number of other minerals are called varieties of jade; these include some found in the western United States and in Mexico.”

In his book Treasure Hunting in British Columbia, Ron Purvis lists a third major variety, chloromelite, mined principally in Peru by natives who valued hard, sharp characteristics for the making of tools and weapons.

For the technically minded, Van Nostrand’s Scientific Encyclopedia defines the popular mineral as being “either a compact actinolite called nephrite, a variety of amphibole, or jadeite, a mono clinic pyroxeme”.

Today, jade (okay, nephrite) is found in several areas of British Columbia, notably at Dease Lake in the north; at Wheaton Creek, 100-odd miles to the south; in the historic gold mining country of Bridge River; and at Tatla Landing near Fort St. James.

In 1968 the British Columbia provincial government recognized the honourable role jade has played in provincial lore and placed a Crown reserve on the Fraser River between Lillooet and Hope, long the most popular hunting ground for rockhounds. Then Mines Minister Donald Brothers explained: “It will be lawful for any person to search for and to remove jade from the area hereby reserved for his sole use and pleasure and without the need for acquiring a Free Miner’s Certificate.”

This far-sighted move, made at the same time jade was formally dedicated as the province’s official mineral emblem, was intended to insure that commercial interests did not gain control of the area.

Perhaps it is within this region that the fabled “mother lode” of jade is situated. Solid mountains of the mineral have, in fact, been uncovered in recent years; but I am getting ahead of my story. Indians around Lillooet long believed that Skihist Mountain was nothing less than pure jade, guarded by evil spirits which inflicted painful illness upon anyone who attempted to mine the fabled peak. Ironically, they were not far wrong (in the former sense), it having been found that rugged Mount Skihist does contain a mineral known as vesuvianite, a close relative of jade. Named after the Italian volcano where it was first discovered, this handsome mineral (also known as californite) is often mistaken for jade as it comes in striking green as well as in lime, yellow and brown.

Most jade in British Columbia is recovered in boulders from in the shallows of or in the gravelled backwaters of a river such as the Fraser. Jade’s most outstanding characteristic, of course, is its striking shade of green, although it is to be remembered that it also comes in varying shades of green and in white. Upon finding a promising stone (usually polished by the river to a smoother finish than its more common neighbours), a rockhound confirms its identity by dipping it in the stream or, if it is too heavy, wiping it with a wet palm.

Despite a weathered exterior, which has been described as looking “somewhat like liver before slicing by the butcher,” the stone should now be richer in colour, and the next step is to chip away a fragment with the rockhound’s indispensable rock hammer. Upon holding a fragment to the sky, one should be able to almost see through the thin, jagged edges, jade being opague or translucent, rather than dense.

This is the critical test, such misleading lookalikes as serpentine and bowenite permitting no passage of light through even the finest sliver. Serpentine also reveals itself by showing the scratch of a knife blade whereas jade, being much harder, remains unmarked.

Some rockhounds, however, are convinced of the authenticity of their find only after cutting and polishing a piece of the rock, jade then giving a burnished glow that is unmistakable and which accounts to a great extent to its ages-old popularity.

Unfortunately, as most novices soon find out, if all that is green is not jade, all that is jade is not valuable! As with anything, quality counts. Besides richness and purity of colour, jade is judged by its absence of flaws such as hairline cracks and darker spots which can give it a mottled appearance. Another fault not uncommon among jade toted home by beginners is over-zealouness, the ecstatic rockhound shattering his brittle prize with too many (or too hard) blows of the hammer!

Earlier, I mentioned the search for a mother lode, or ‘mountain of jade.’ Long a tantalizing legend among Indians and the first gemstone seekers, the idea of discovering a concentrated source of rich jade was discounted—until several husky British Columbians matched skill and determination and came up with what was reported to be nothing less than the Eldorado of jade.

Best known of these prospectors was Mrs. Winnifred Robertson, famed as the ‘Jade Queen,’ who, after years of studying and searching, found her mountain of green at the southern end of Takla Lake in 1968.

Others have been as fortunate. Months after, 45-year-old Bob Smith, his wife and his brother reported the striking of a rich claim of jade at Brett Creek, near Lillooet.

Smith told reporters that he and brother Ed had noticed jade in the creek and had eventually located the vein, tracing it for “a length of three miles... We opened up the area and went down 100 feet below the serpentine. There is a serpentine capping over it. Then we hit it. In the past month we have taken out 200 tons of jade of medium and gemstone quality.”

A year later, Harry and Nellie Street of Bralorne announced the recovery of a boulder of solid jade which they estimated to be worth $45,000.

In January 1970, Kuan-Yin Jade Industries Ltd., Toronto, announced claims in British Columbia’s Ogden region to be worth between $400,000 and $20 million at the current market price of between $1 to $50 a ton.

During Expo ‘70, a 23-ton jade boulder valued at $1.5 million was gently loaded aboard a freighter for the trans-Pacific voyage to Osaka where the giant green stone, one of its sides polished to a mirror-like finish, was to be displayed at the British Columbia pavilion. Despite its being dropped during unloading (damaging the freighter), the cumbersome giant reached Osaka intact.

Ironically, despite jade’s legendary reputation as a good luck charm, it may have led to the deaths of two Americans in an air crash near Prince George, in September 1970. Investigating RCMP found that the pilot and passenger had attempted to fly out 1200 pounds of jade—200 pounds over their Piper Commander’s load limit—when they plummeted 100 feet onto the runway during takeoff.

This small piece of jade is just a sample—there are mountains of the semi-precious jewelry stone in British Columbia.

At that time at least two Vancouver firms were exporting gem quality jade around the globe, the price, depending upon quality, ranging from 75 cents to $50 a pound. Both companies claimed to be in control of mountains of the mineral and able to supply world demand for years to come.

In 2008 it was reported that Jade West Resources, which was mining 250 tonnes annually from the mountains around Dease Lake in northwestern British Columbia, couldn’t “dig fast enough to feed China’s insatiable appetite for the green gemstone”. That’s because the minesite, near the Alaskan panhandle, was so remote and subject to extreme weather conditions for much of the year. Ninety per cent of the company’s $3 million annual production went to China where even some of the Beijing Olympic where the gold, silver and bronze medals had jade inlays. (In 2008, by the way, jade prices ranged from $2 a kilo for tiles to $100 per kilogram from gemstone quality.)

However, as Jade Queen Winnifred Robertson found out, development does not necessarily lead to riches—not because the jade is lacking in quality but because the Western world, with the exception of Germany, showed little interest in the beautiful stone which is almost revered in the Orient.

At last report, Mrs. Robertson was undiscouraged and marshalling her energies to promote jade in a totally new field: as a building stone which, she said, would rival the best Italian marble in handling and in beauty.

Why not? More than a century ago, remember, aside from the Chinese miners, you couldn’t give jade away!

And do not despair that all the good jade (nephrite) has been found; it is believed that British Columbia is “home to half the world’s jade resources”!

Some Favourite British Columbia Gem Hunting Locations

(as suggested by the British Columbia government):

Blue-grey Agate – Shaw Springs, halfway between Lytton and Spences Bridge on the Thompson River

Green Hyalite and common Opal – on the south slope of Savona Mountain

Agate, Hyalite, Jasper and Petrified Wood – in the banks of the creeks which flow into the eastern end of Kamloops Lake near Transquille

Agate, Amethyst-filled Agate Geodes – in Robbins Creek on the Robbins Range Escarpment just south of Monte Creek

Agate – south end of Monte Lake

Blue-Grey Agate, Prase and Amethyst – Squilax Mountain and Turtle Valley, six miles south of Chase

Agate, Jasp-Agate, Jasper, Opal, Feldspar Crystals – four miles south of Penticton

Rhodonite, Hausmannite and dark red Jasper – western boundary of the Village of Keremeos

Agate, Petrified Wood, Opal, Opalized Wood and Fossils – Vermillion Bluffs on the north side of the Tulameen River, two miles west of Princeton

Amethyst and Agate – Scottie Creek, 18 miles north of Cache Creek

Rhodonite – Sheep Creek Bridge on the Fraser River, 15 miles west of Williams Lake

Agate Nodules and Opal - Macalister, south of Quesnel on opposite side of the Fraser River

Thunder Eggs (weighing up to 40 pounds!), Opal, Jasper and Agate – in the area of the historic Gang Ranch in the Empire Valley

Agate, Jasper, Amber, Opal, Sand Concretions and Thulite – 50 miles northwest of Quesnel in the Blackwater Creek area

Red Agate (aka Omineca Agate) – on the shores of Francois Lake Petrified Wood and Jasper Agate – in the dry bed of the Nechako River

Rhodonite – at the site of an old manganese mine on Hill 60 near Lake Cowichan, Vancouver Island

Agate, Garnet, Grossularite, Jasper, Jade, Nickel Silicate, Porphry, Rhodonite, Serpentine, Sillimanite and gold – in the bars of the Fraser River at low water (winter).

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.