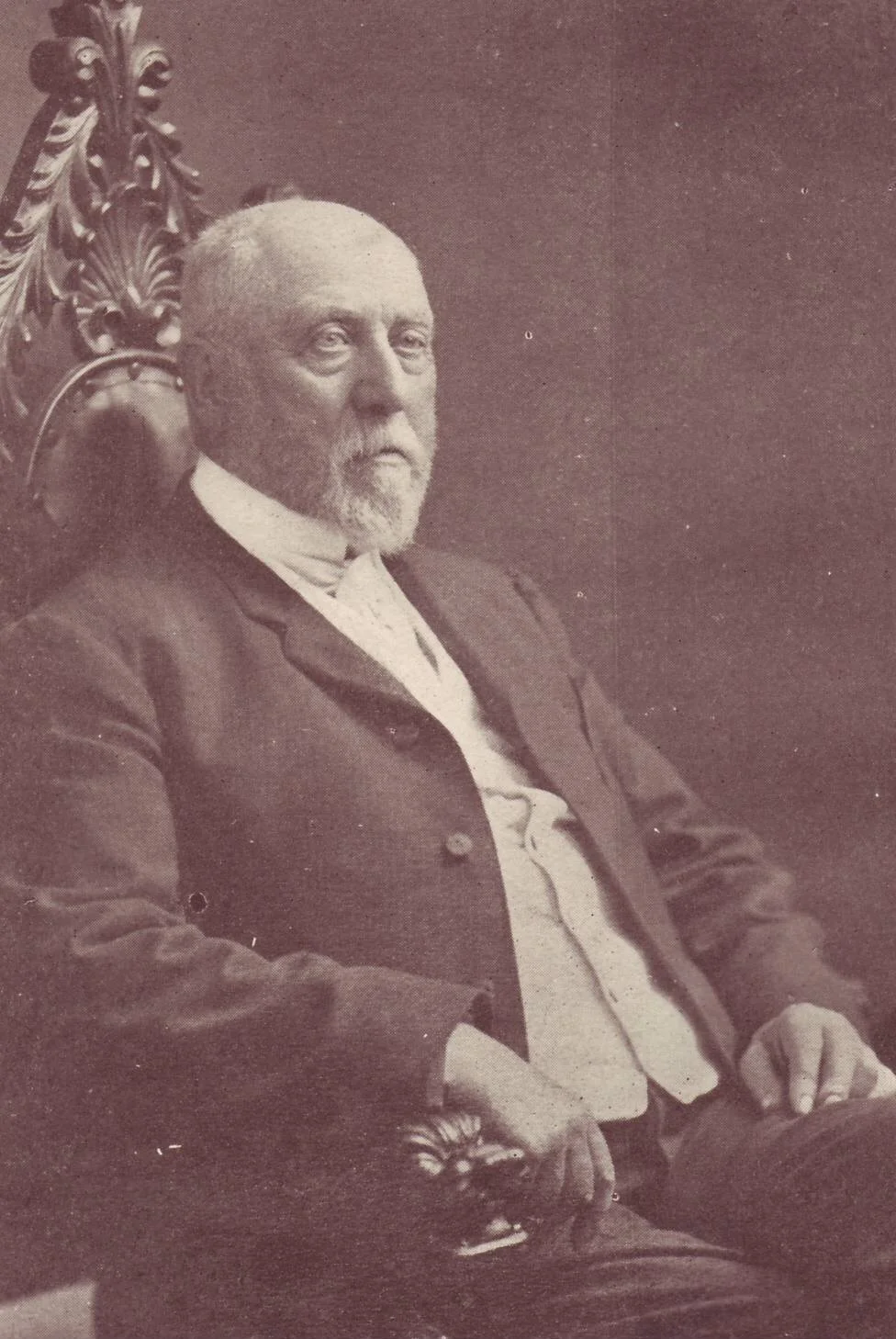

Happy Tom Schooley

A foggy fall shot of the historic Ross Bay Cemetery in Victoria B.C. So wrote Sheryl Walker of this moody scene used as a cover photo for the Old Cemeteries Society’s Stories Beyond the Graves in Victoria, B.C. It’s that imposing dark headstone on the left that prompted me to dig into my archives for this week’s Chronicle.

Genealogists have a field day with Vital Statistics; they’re a treasure chest for family researchers and historians alike.

But, of course, they really don’t tell you much beyond the barest of bones. Take, for example, this one:

BIRTH 1826

DEATH 22 May 1874 (aged 47-48)

Victoria, Capital Regional District, British Columbia, Canada

BURIAL Unknown

Now what’s an author/historian/storyteller supposed to do with that?

Not a heck of a lot, obviously, unless you have access to other sources. So, to answer the old puzzle, which comes first the chicken or the egg, the answer is to seek out details like vital statistics after we’ve discovered a story.

Often that source is a newspaper. Which is how I chanced upon the fascinating man whose statistics are given above. When I worked for The Daily Colonist, as it was when I was still a lad, I’d spend my evening supper break in the morgue, or library, digging through what were known as the vertical files—clipping files of old news stories, some of them going back decades.

Or straining my eyes on the microfilm machine with its green light and purple print. How I cursed the genius who came up with that colour combo; an hour or so was almost sure to bring on the start of a headache even for young eyes.

But the point of the exercise, after all, was to access the wealth of old Colonists and Victoria Daily Times with their millions of stories on those rolls of 35mm film. To a newbie such as I, who just beginning to grope my way into the incredible repository that is our provincial history, that microfilm machine, for all its crudity, was the key.

So I carried on, straining my eyes, making notes then advancing to using a typewriter alongside. To get to the point, one of those great discoveries came when, working my way through the British Colonist a year at a time, I came to 1904—and to D.W. Higgins.

I’ve introduced you to D.W. several times in these pages, even letting him tell you about the Christmas dinner that almost cost him his life, in his own words. What I found in those 1904 Colonist’s were a series of articles, reminiscences, he later compiled in two books. Highly collectible today are The Mystic Spring and The Passing of a Race.

Modern researchers such as the late, local David Ricardo Williams have criticized Higgins’ claim to have been on the inside of almost every major news story over his 50-year-long journalistic and political career, most of it in Victoria. In particular, they fault him for his use of reconstructed dialogue.

So be it. I accept that Higgins was, in fact, privy to details of the great political events, many of the leading pioneer personalities and details of the major crimes of his day. I do acknowledge that his accounts aren’t always 100 per cent accurate (who is?) and that he likely embellished his own role in them.

But I refuse to look a gift horse in the mouth. To read Higgins’ stories, for all their purplish prose, as judged by our contemporary standards, has been a joyful voyage of discovery for me. The subject of this week’s Chronicle was one of the very first of D.W.’s stories that I found and I’ve been following in his shadow ever since.

The story of ‘Happy’ Tom Schooley, as told here, is as much mine as it is D.W.’s but he experienced and recorded it first, a fact I respectfully acknowledge.

Speaking of cold statistics or officially recorded facts, as I did earlier, here are two more. The inscription on the headstone in the photo reads: FORMAN, Henry, Age: 45 y, d. 1874/01/23 Victoria, BC, Plot: A.48.25.E

And this one: Thomas Schooley: Miner, age 38 (sic), executed for the murder of Henry Foreman.

Ah, now we’re getting somewhere!

* * * * *

As noted earlier, there was little that David W. Higgins failed to see or do during his career as a pioneer journalist. Whenever anything of note occurred, you could be sure Mr. Higgins was on the scene or soon learned the “inside” facts.

Of all the characters he met, from brawling gold camp to provincial legislature, one of his most memorable acquaintances was “Happy Tom”.

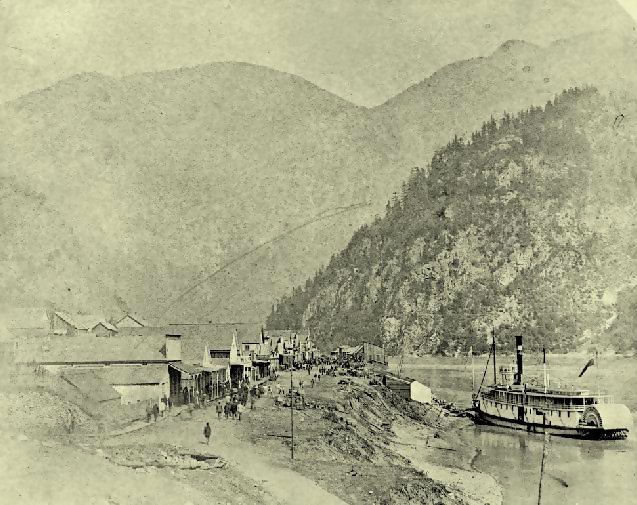

It was in a 1904 newspaper article, 30 years after, that he told the story of Tom Schooley. A tragedy which began one bright morning in the boom town of Yale, and ended, on another spring morning, in the grim courtyard of Victoria’s Bastion Square.

In 1859, Nova Scotian Higgins, having temporarily forsaken his pen for a gold miner’s pick, found himself among the rowdy populace of Yale.

The riverside main street of Yale, B.C. where Higgins met the young whistler. —Wikipedia/Public Domain

“I had risen early,” he recalled, “and after a dip in an eddy in front of Yale flat, was slowly picking my way along the bar towards a trail that led to the bench where the principal business houses were located when I saw approaching a tall, slim youth of perhaps 18 years.

“He leaped from boulder to boulder as he advanced, seeming to scorn the narrow path which led around the rocks. He was active enough for a circus acrobat, I thought, as I paused to watch his agile movements.

“As we neared each other the youth began to whistle, pouring forth from his lips the most melodious sounds. The airs selected were from songs that were popular at the time and the execution was so exquisite and harmonious that I paused to listen so that I might draw in every note.

“When he found that he was observed, the youth ceased to warble and, dropping from a boulder on which he was perched, bashfully awaited my approach.”

If the ragged young stranger were shy, Higgins was not. Striding forward with outstretched hand, he introduced himself and asked the youth why he was so happy. Had he struck it rich?

Quite the contrary, replied the other; he’d found nothing. He whistled from the sheer joy of living. As their conversation developed, Tom–“My name’s only Tom; call me that and I’ll always answer” –expounded his light hearted philosophy to the cynical journalist.

“I never let trouble bother me—I shed it like a duck sheds water from its back. I can’t imagine how any man can be unhappy so long as he walks straight and acts right. I don’t mean to do anything wrong in all my life, and if I don’t have good luck I’m never going to fret.”

The world-weary Higgins couldn’t have been more delighted than Diogenes finding his honest man. Laughing, he christened the youth ‘Happy’ Tom.

“Your philosophy is sound and good and your face shows that you have a light and happy heart!”

They became friends, Tom proving to be a popular favourite in Yale. As he walked its dirt streets he “filled the air with melody and people ran to their doors to listen to the sweet sounds”. No social gathering was considered complete without the friendly whistler.

By the time Higgins moved on, in 1860, he’d grown quite attached to his friend, hailing him as “an exemplary young man. He would neither drink liquor nor smoke. He was witty without being coarse, rude or offensive. Swear words were strangers to his lips, and honesty of purpose and kindly thought shone from the depths of his clear eyes and lighted up his ingenuous countenance.”

“I had many conversations with him,” he wrote long after, “and found him very intelligent. His uniform good nature was magnetic and he grew upon me.”

Came at last the sad farewell. As the journalist’s canoe swept downstream, his last memory of Yale was that of Happy Tom “perched on a huge boulder, still pouring forth his happy soul in sweet and far-reaching melody”.

The years passed with Higgins busily reporting public affairs, becoming active in politics and advancing with his adventurous times. He ultimately owned both the Daily British Colonist and the Victoria Chronicle and, by 1874, the prospering newsman had long forgotten his exuberant friend, Happy Tom.

When their paths did cross again, it was under circumstances far different from those of their first meeting...

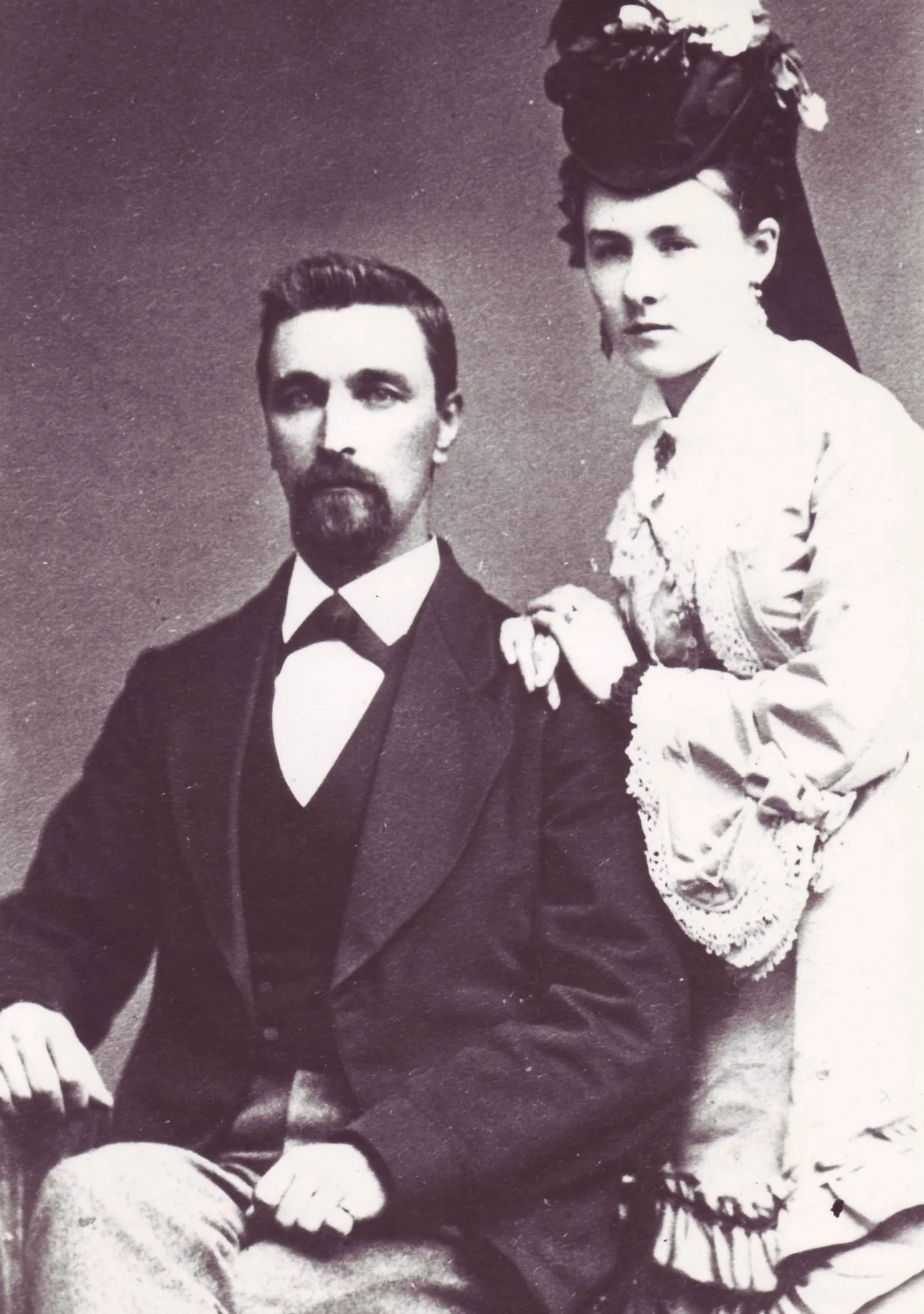

Tom Schooley and his bride before life went sour.... —Author’s Collection

On a dismal, wet January evening, the stocky editor was leaving his Government Street office when he was accosted by coal merchant Richard Brodrick, who panted, “Harry Forman’s been shot!”

Instantly forgetting the mud holes, Mr. Higgins headed for James Bay at a run, breathlessly reaching the seven-room St. Lawrence Street cottage of Alderman Henry Forman a few minutes later. Pounding on the door brought no response, so he tried the latch. Thwarted, he raced around to the kitchen door. It, too, was locked so the persistent newsman tried the windows. All were secure.

By then he’d circled the bungalow and found himself again at the front door—just as Constables Clarke and Beecher arrived to inform him that he was lucky that he’d been unable to enter the cottage–there was a heavily armed, dangerous fugitive inside.

Without even pausing to consider what may have been a very close call, Higgins was soon jotting down the gory details. He had to scribble fast, as Clarke and Beecher were busy kicking in the door; an occupation they hastily abandoned when the unseen occupant loosed three shots in their direction.

Hurrying across the street to the home of James Anderson, where the wounded man, his wife and daughter had taken refuge, Higgins found Forman dying of two pistol wounds. Forman was making a formal statement to the effect that he’d returned home at six that evening, as usual, to find his son-in-law, Thomas Schooley, roaring drunk.

Which also was usual, according to subsequent investigation.

A loaded revolver in one hand, a demijohn of wine in the other, Schooley had commandeered the dining room. Accordingly, the Formans, Mrs. Schooley and her infant daughter retreated to the kitchen. Forman was just raising his fork when Schooley lurched through the doorway, screamed a “fearful oath,” and fired.

The heavy ball shattered the alderman’s hand.

“With a cry of agony [he] rose to fly,” in the colourful prose of the Colonist, only to catch a second, fatal ball in the chest. Somehow the hysterical women helped him to Anderson’s, where he succumbed the next morning.

After witnessing Forman’s deposition, Higgins ran back to the cottage. All was quiet as the constables awaited reinforcements in the form of more police and militiamen. But it was through the volunteered services of a Colonist reporter, tiny Englishman William H. Kay, that Schooley was captured without further bloodshed.

The heroic reporter carefully jimmied a kitchen window and slipped into the darkened house. Ears straining to catch the slightest sound, eyes vainly trying to pierce the night, Kay crawled from room to room—after he’d finished Forman’s untouched dinner!

Asked at the trial by the attorney-general who was prosecuting for the Crown, what the two constables were doing all this time, Kay replied that they were enjoying their share of the meal, which he’d passed out to them!

His ghoulish repast completed, Kay searched for Schooley. He found the gunman—by clipping him with the dining room door. With a leap he tackled the “dead drunk,” but swiftly sobering murderer. At his yell, the constables burst in to and relieved Schooley of a cocked revolver, two derringers and a Bowie knife.

Finally came the four-day trial, the inevitable verdict and sentence of death. The nine weeks remaining to Schooley fled all too quickly, although not without exciting moments for the city. Particularly when it was learned that several guards had been bribed to look away while his death watch was overpowered, Schooley whisked to the American side by tug.

The plotters were arrested, the corrupt guards replaced, and Schooley faced his end on schedule.

Three days before the fateful dawn, Higgins was admitted to the death cell. Schooley, his thick black hair turned silver, was calm and pleased at having company. Without prompting, he told the editor he’d “acted within his rights in committing the murder—that he was merely an instrument to punish Forman”.

Schooley believed, with or without foundation, that he’d been tricked into marrying and that his wife had been unfaithful.

There did not seem to be much more to say and as the journalist turned to go, he chanced to remark that he’d once lived in Yale. To which Schooley smiled, “Yes, I knew you there.”

“Do you know,” Higgins frowned, “that I have been told by a hundred different persons that you were there in my time and yet I cannot recall your features?”

Sorrowfully, the condemned man asked, “Are you quite sure that you never met me on the Fraser River?”

“Quite.”

The next scene is best left in Higgins’ own words:

“Again he seemed to drop into deep thought. Then he rose to his feet. The setting sun shone through the little grated window that furnished air and light to the cell and a golden beam danced like a sprite along the whitewashed wall. The doomed man raised a hand as if he wished to grasp the fleeting ray. When he turned towards me again his eyes were filled with tears.

“‘And you don’t remember me?’

“‘No, I cannot recall a line of your face.’

“‘Perhaps this will aid your memory,’ he said. And then from his lips there issued a stream of delightful notes that reminded me of the diamonds and flowers that fell from the mouth of the good young woman in the fairy tale.

“I leaped to my feet, surprised and overcome by the revelation that the music conveyed.

“‘Good heavens,’ I cried, ‘You don’t mean to say that you are—you are—“Happy Tom”?’

“‘The same,’ he said. ‘Happy no longer, but the most dejected and wretched wretch on the whole of our Maker’s footstool! Fifteen years ago I was the merriest and happiest man in the colony. Today I am a miserable felon (he pointed to the heavy shackles that encircled his ankles), and I’m about to die.

“‘After you left Yale I fell into bad company and took to drinking and gambling and here I am at last—the natural end of all such fools. Had I been sober I would never have married and there would have been no murder.’

“As I extended my hand the convict said: ‘Mr. Higgins, I have one request to make of you. Will you come and see me hanged on Friday?’

“‘No!’ I replied, ‘ask anything else and I will grant it. But not that—not that.’

“‘It’s my last request—I insist,’ he urged.

“‘Oh! I cannot,’ I replied.

“‘What?’ he said caressingly. ‘You will not come and see poor Happy Tom—the boy you christened in the long ago—die like a man? Come; say you will. I shall never ask anything more of you!’”

Thus it was, on another spring morning in May, while song-birds “were bursting their throats with songs of gladness,” that a subdued Higgins stood in the silent crowd circling Bastion Square.

As Schooley “crossed the yard to the scaffold his form showed not the slightest tremor, his face wore its natural hue. As he advanced his eyes wandered over the group of officials and spectators until they encountered mine. A smile of recognition flitted across his face and then it seemed as if the intervening years were rolled away and that he and I were suddenly transported to the waterfront at Yale and that he had just told me his name was only Tom and I had named him Happy.”

Minutes later, it was all over. As the crowd dispersed, only one mourned the good man who had once been: Editor Higgins for his old friend—Happy Tom.

* * * * *

I have three post scripts to this tale. As described, Tom Schooley was hanged in Bastion Square next to the Police Barracks as was the custom until the new provincial jail was built at Topaze and Hillside. Schooley was one of the last to mount the gallows in the Square beside the Inner Harbour.

For years the former provincial court house, built on the site of the Bastion Square police barracks, served as the B.C. Maritime Museum. —crdcommunitygreenmap.ca

Fast-forward a century and a-half and John Adams and company of Discover the Past Walking Tours (www.discoverthepast.com) will guide you to—almost—the very spot where Schooley’s and other hangings were carried out. The former provincial court house, for years the Maritime Museum of B.C, now covers much of the site which, according to Adams, and not surprisingly to many, is haunted.

Secondly, incredibly, you can buy an original copy of my Colonist article on Happy Tom Schooley on the internet for $15US!

Back to Schooley’s drinking and rage that led to his shooting his father-in-law at the dinner table: that he’d lost his money, that he’d been tricked into marriage, that his wife had been unfaithful to him.

Maybe yes, maybe no or, perhaps, in part or in combination of. Years ago I met a man who collects ephemera (papers, letters, documents, etc.). Among his collection was a copy (I mean an original not a photocopy) of Tom Schooley’s will. He hadn’t died penniless and he left his entire estate to his wife and daughter.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.