High Noon in Victoria

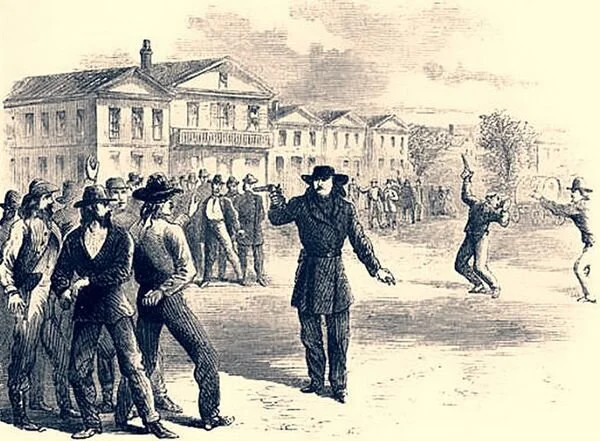

This is what we’ve come to recognize through movies and TV: Wild Bill Hickock, after fatally wounding Dave Tutt in the chest in a street shoot-out, warns off Tutt’s friends. But in ‘downtown’ Victoria? —Illustration from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867.

In my promo for this week’s Chronicle I noted that, as recently as the 1960s, Victoria was so quiet, t’was said they rolled up the sidewalks at night. It was even called a cemetery with a business section.

Times have certainly changed, if not for the better, crime-wise.

But let’s go back to 1858 when what had been a sleepy Hudson’s Bay Co. fort was transformed, almost overnight, by the magic word, “Gold!”

Gold in “Fraser’s” River that drew an estimated 25,000 adventurers north from the tapped-out diggings of California to the new El Dorado of the future British Columbia.

Journalist D.W. Higgins, whom we’ve met before in these pages, has painted a colourful and unflattering portrait of some of these arrivals: “A worse set of cut-throats and all-round scoundrels...from all parts of the world never assembled anywhere…”

He was referring to Yale and I’m talking about Victoria but it was through Victoria that most adventurers, the good and the bad, made their way to the Mainland diggings. Upon arrival from San Francisco they camped here until they could make their way up the Fraser River to, so they hoped, fortune.

This is what all the excitement was about: a gold nugget. —Royal British Columbia Museum photo.

Not all of them made it. Accidents and misadventure were inevitable. One of them, George Sloane died in a gunfight at high noon—not at the OK Corral, not in Dodge City, but in what’s now downtown Victoria.

Victoria, the City of Gardens? Surely I jest!

* * * * *

The busy intersection of Blanshard and Burdett streets has changed over the past 160-plus years.

Today, passers-by would find it hard to believe that this was virgin forest in 1858—or that, here, two pioneers faced each other in Victoria’s only recorded fatal duel. For the background to this intriguing gold rush tragedy, we’re indebted, once again, to journalist David W. Higgins, onetime owner-publisher of the Colonist, MLA and Speaker of the House.

Drawn, like 10s of 1000s other others, to California by the excitement which followed the great gold rush in 1849, the Halifax-born Higgins had his own fledgling newspaper, the Morning Call, at the age of 22. He seems to have been blessed with “the knack of meeting extraordinary people in extraordinary situations,” as one historian has noted. Young Higgins found himself in San Francisco in time to witness the city’s infamous clean-up of corruption and crime by vigilantes.

Higgins’s introduction to outpost Fort Victoria proved to be as exciting.

When the cry of “Gold!” resounded from the British Columbia Interior in 1858, Higgins joined in the stampede to this latest ‘El Dorado.’ With 100s of men, women, and even some children, he crowded on board a decrepit steamship so packed with human cargo that every last square foot of deck space, the saloon and passageways were pressed into service as sleeping accommodation.

“Ho! For Frazer River” [sic]. Illustration by J. Ross Browne from "A Peep at Washoe" in Harper's Monthly Magazine, December 1860. The unknown artist has captured the feeding frenzy of the 1000s of gold seekers who sailed from San Francisco during the Fraser River and Cariboo rushes.—Courtesy Wikipedia Commons.

Sprawled on bedrolls or on no ore mattress than the clothes they wore, passengers withstood cold, damp, discomfort and seasickness as best they could during the hazardous passage up the Pacific coast. Only a few hardy souls escaped the “abandon and despair and hopelessness” during the voyage, among them our reporter, D.W. Higgins, who also was one of the very few to enjoy the comparative luxury of a stateroom. His two cabin mates were George Wright, who was destined to be a successful B.C. businessman, and George Sloane, a young Englishman fresh from college.

Two Americans and a second young Englishman shared an adjoining cabin. Unlike the scholarly Sloane, who amused himself by displaying his knowledge of Greek, Latin and poetry, his countryman was of an entirely different cut.

John Liverpool, or ‘Liverpool Jack’ as he identified himself, preferred the pastimes of smoking, gambling and drinking, the latter made possible from his constant companion, a demijohn of brandy.

Aboard a ship that was overcrowded almost to the point of suffocation, without adequate sanitation facilities, with little food—and what there was of that was of wretched quality—the garrulous Liverpool Jack offered a welcome means of escape to the unhappy passengers who eagerly listened to his glowing tales of adventure. Their diversion was short-lived, however, as Jack’s attention was soon taken by a single female passenger.

Young and attractive, despite her being pale and thin and her constant expression of “wretchedness and misery,” Miss Bradford had early attracted Higgins’s attention, too. But, before he could muster the nerve to approach her, the swashbuckling raconteur introduced himself to her. Liverpool Jack soon monopolized Miss Bradford’s time, seldom leaving her side although he did find time to mention to Higgins that she and he mother had been on their way to Victoria to open a boarding house.

But the mother had died days before and the daughter had been robbed of her savings aboard ship. Faced with being penniless and alone, she’d slumped dejectedly in a deck chair until taken under his wing by Liverpool Jack.

Days later, as the wheezing Sierra Nevada laboured towards British Columbia, Higgins’s room mate George Sloane returned to their cabin to excitedly describe his having met a young woman aboard ship. When it became apparent that the object of his interest was the same Miss Bradford who’d been taken in charge by Liverpool Jack, George Wright cautioned his travelling companion against antagonizing the brandy-swilling gambler as he had a notorious reputation.

Unimpressed, Sloane suggested they take up a subscription to relieve the woman’s financial embarrassment. His opening donation of $20 was quickly met by others and, within 10 minutes, he’d collected the princely sum of $100.

Collection in hand, Higgins at his side, Sloane approached Miss Bradford. As the young man stammered out an explanation of the gift, Liverpool Jack listened with obvious hostility. Before Miss Bradford could make a reply, Jack cursed the visitors, grabbed the money from Sloane’s hand and threw it overboard.

“Look here!” he shouted. “This girl is not a beggar and if she stands in need of money I have enough for both.”

“You damned cad!” replied the shocked Sloane.

He had no chance to say more as Liverpool Jack lashed out with his fist and caught him squarely between the eyes. As the object of their animosity threatened to faint (Higgins doesn’t say what he was doing all the while), Sloane stumbled backwards, recovered himself, and lunged forward. Clutching Liverpool Jack around the throat with his left hand, he delivered several pile-driving blows with his right fist to the gambler’s face. In seconds, Jack was reduced to a bloodied, semi-conscious pulp which Sloane unceremoniously dumped into the deck chair hastily abandoned by the lady.

Back in their cabin, a steward attended to Sloane’s blackened eyes with a piece of raw meat then all turned in for their final night aboard ship. Early next morning, the Sierra Nevada disgorged her motley cargo at Esquimalt, Higgins recalling half a century later that, although he hadn’t watched for them, he saw neither Miss Bradford nor Liverpool Jack during disembarkation.

This pleased him as he shared George Wright’s concern for Sloane’s well-being. Jack’s reputation as a blackguard and his poor performance aboard ship didn’t bode well for their travelling companion’s safety should he and the gambler meet again.

Liverpool Jack and Miss Bradford were temporarily forgotten during the hours-long hike to Victoria. Almost 50 years and a full and adventurous career later, Higgins recalled his arrival on Vancouver Island. His introduction to a formerly quiet Hudson’s Bay Co. trading post that had been transformed into a tent city of some 10,000 people was memorable. From all four quarters of the globe, of almost every nationality and hue, they shared a common goal: to strike it rich on Fraser’s River.

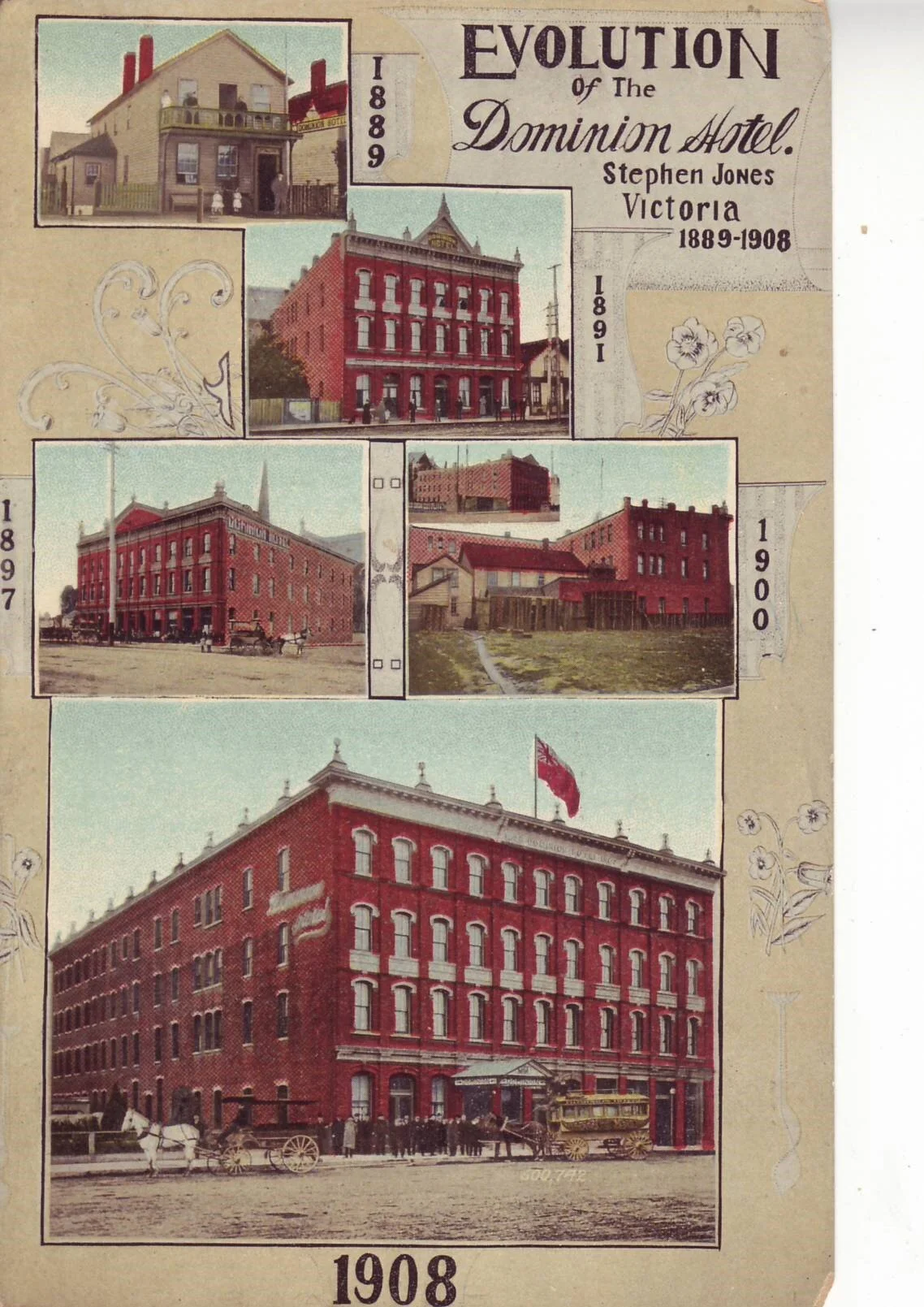

Even the swamp lands of what would become upper Fort and Johnson streets were crowded with tents and lean tos as was the forest of oak, cedar and fir where the legislative buildings now stand. It was near the site of the latter-day Dominion Hotel, at Yates and Blanshard streets, that Higgins, Sloane and two others named Crickmer and Johns pitched camp in a forest clearing.

An old postcard showing the Dominion Hotel, 1888-1908. In 1858 this site, where Higgins and company camped, was swampland. It’s now one of the busiest areas of downtown Victoria, --Author’s collection.

After a comfortable night spent on a bed of fir boughs, it was agreed that Crickmer would have the honour of cooking breakfast. He busied himself accordingly, only to soon rejoin the others inside the tent. After carefully dropping the flap over the doorway, he whispered, “Boys, who do you think are our next door neighbours? Guess.”

When they shrugged, he explained that an adjoining tent was occupied by none other than Liverpool Jack and Miss Bradford, their late companions aboard the Sierra Nevada.

Sloane, jumping to his feet in rage, swore he’d kill Liverpool Jack if he’d wronged the girl. He’d have stormed the other tent had not his three older, wiser companions restrained him. They urged him to forget Miss Bradford, saying that when he ‘d experienced more of life, he’d be able to accept such things without wonder.

Slowly, with difficulty, Sloane regained his composure and finally promised that he’d make every effort to avoid the gambler and the girl next door.

They were interrupted at that moment by a visitor who, having lifted their tent flap to introduce himself, warned them to be on their guard against a desperado from San Francisco whom he’d just spotted in the neighbourhood: Liverpool Jack!

The four finished breakfast in silence, each man deep in thought. That done, they decided upon a look around town, bought lunch and returned to their tent about 5 o’clock to prepare supper. As they enjoyed their beans, bacon and flapjacks their neighbours appeared momentarily. Miss Bradford hurried into the tent she shared with Liverpool Jack without acknowledging them.

Restless, Higgins and Johns returned to town to attend a minstrel show at the Star and Garter Hotel. About 9 o’clock, upon leaving the hotel, their curiosity was aroused by an excited crowd that was headed in the direction of their camp.

Following, they were greeted by a tearful Crickmer who had a sad story to tell them.

He and Sloane, he said, had been smoking their pipes beside the fire when Liverpool Jack appeared with several companions. With a sneer, Jack informed them that he And Miss Bradford had been married that morning then challenged Sloane to a duel. Although obviously stung by the gambler’s challenge, Sloane remained calm, saying he didn’t owe Liverpool satisfaction.

Not to be denied his need to avenge himself for his shipboard beating, Jack advanced to within a few inches of Sloane, said he’d brand him as a coward if he didn’t fight—and spat in his face.

“No!” cried Crickmer as he implored Sloane, now shaking with rage, to ignore the challenge. Sloane refused to listen and Liverpool’s ‘seconds’ forcibly prevented Crickmer from further efforts to dissuade the combatants.

As he watched in horror, the antagonists squared off, Sloane armed with a borrowed revolver. Jack, the more experienced of the two, positioned himself to the west so that Sloane was squinting into the setting sun.

Both men acknowledged their readiness, a second gave the signal to fire, and two shots shattered the evening silence. Sloane’s bullet spun harmlessly into space—but Liverpool’s found its mark in his heart. With an agonized cry, he pitched forward.

By the time Higgins and Johns reached the scene, George Sloane lay cold and still, his handsome features glazed with a fine dew. Higgins and the others arranged for their late comrade’s funeral and a coroner’s inquest ruled that he’d been murdered. But no arrest was ever made, Liverpool Jack, his bride and his henchmen having disappeared.

The trigger-happy gambler ultimately returned to what he considered to be the friendlier pastures of San Francisco. He must have forgotten that the Vigilance Committee had introduced a New Order; for killing a seaman he was duly tried, convicted and hanged.

Long afterwards, Higgins was reminded of the tragic George Sloane by a letter from fellow adventurer Crickmer who’d also returned to the Bay City. It seems that Crickmer often saw the hapless Mrs. Liverpool Jack, nee Bradford, who’d inadvertently set in motion the chain of events that led to Sloane’s death. She wandered the streets of the city at night, he said, her eyes aglow with an unholy light, as though she were possessed by an evil spirit.

Victoria has known at least three ‘Liverpool Jacks’ in its history. The villain in the city’s only recorded fatal duel was the first, and most certainly, the worst.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.

![“Ho! For Frazer River” [sic]. Illustration by J. Ross Browne from "A Peep at Washoe" in Harper's Monthly Magazine, December 1860. The unknown artist has captured the feeding frenzy of the 1000s of gold seekers who sailed from San Francisco during th…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e94af42437b8e5cb51b7789/1627396093982-0RMNGU4Q9JAQ8W508VS5/Washoe_Frazer_River.jpg)