Hiking Henry Croft’s Dream Railway

“Have you hiked the old Mount Sicker Railway grade?”

Or: “How do I find the old Mount Sicker Railway grade at Crofton?”

Jennifer Goodbrand and Sophie inspect some of the cribbing of the historic Lenora, Mt. Sicker Railway grade on Mount Richards. —Author’s Collection

It’s a question put to me from time to time, more frequently lately, as more and more people embrace hiking, with its great outdoor scenery, fresh air and the joy of exploring the Cowichan Valley afoot.

We are truly blessed with the Trans Canada and Cowichan Valley trails, the former Canadian (Northern Pacific) National Railway and the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Cowichan Lake Subdivision, respectively.

According to the CVRD, the Kinsol Trestle alone draws an estimated 100,000 visitors a year; I don’t know if they’ve ever tried to calculate the numbers of hikers, cyclists and horseback riders who use the rest of these two major trail systems.

But how many know about, let alone have tried hiking, the narrow gauge railway that linked the Lenora copper mine atop Mount Sicker to the deep water harbour at Crofton?

Obviously, the Trans Canada Highway interferes with the old grade as have several property owners, some of whom have obliterated all signs of it on their lands, particularly west of the TCH.

But there are stretches, in particular the famous “Switchbacks” and the Chinese navvies’ cribbing, that are almost pristine—if you know where to find them.

* * * * *

Some things never change, it seems, or at least they don’t for me. Every time I drive up-Island and through the Westholme Valley, my attention is divided between the traffic and trying to snatch glimpses of the properties on the left (west) side of the TC Highway.

That’s just before the trees end as you near the Red Rooster (I still call it the Red Rooster) intersection, site of a gas station, restaurant, Russell Farm Market and, to the right, Mt. Sicker Road leading to Crofton. Several houses line the highway on this side and if you dare to look, you’ll see they seem to share a common ‘driveway’ running parallel to the highway.

That driveway, as I describe it, which forms their front yards, is part of the grade of Henry Croft’s narrow gauge railway, built to link his Lenora Mine atop Little Sicker Mountain to, first, the E&N, then on to Crofton which he created as a salt water port to ship his ore directly to a specially-built smelter.

All because he was convinced that his brother-in-law, coal baron and owner of the E&N, Robert Dunsmuir was hosing him to take his ore to Ladysmith for trans-shipment to Tacoma.

Some Chronicles readers will be aware that I’ve told the full story of the Mount Sicker copper boom at the turn of the last century in my book, Riches to Ruin: The Boom and Bust Story of Vancouver Island’s Greatest Copper Mine. My interest in revisiting this saga is, as stated above, because of several requests lately for information on what’s left of this historic railway that was once described as an engineering marvel.

I’ve hiked the old Lenora Mt. Sicker RR grade several times myself and would love to do so again, time and work, my nemesis, permitting.

But it isn’t easy. Stretches of it are overgrown, the original bridges, of course, are long gone so you have streams to cross, and some stretches have been adapted as roads, particularly on the Crofton side of Mount Richards.

Environmental journalist Larry Pym gave it a try last week, as he explained in a brief email: “I took the e-bike to the Lenora mine today and started down the railway grade towards Crofton. I got about 1 km then hit a creek where the bridge had washed out.

You have to put your imagination to work to see this as it once was, a railway atop Mount Sicker. —Courtesy of Larry Pym

“Definitely a hiking expedition, not mt biking. There was some water on the route, and spots where rocks and trees had fallen down but very doable.

“Probably more of the same awaits further down the grade. I hope to hike it in a few weeks.”

Doable, yes, Larry, but there are, as I said, breaks and missing links as you wend your way north eastward from the Lenora Mine towards the Mount Sicker-TCH intersection.

As you descend Little Sicker Mountain’s northern slope towards the Compton farms on Cranko Road (the railway runs on the lower side of the road leading up the mountain to the copper-era ghost towns and the neighbouring Mount Prevost memorial cairn), you have to keep your eyes peeled for the grade which is overgrown by second- and third-growth forest.

(A landmark to look for in this area is the stump of an old cedar tree. You’ll know it when you see it because it’s notched a few feet above the ground. This isn’t the work of a tall beaver or a logger but of lazy navvies who realized it was easier to axe out just enough of the trunk to allow the train to pass than to remove the stump!)

(In fairness to them, it was all hand labour in those days.)

Then the grade disappears until past the Horace Comptom property where it leisurely loops and winds almost due east and comes out at the highway, immediately south of the Mt. Sicker intersection, and heads due south. At some point just before the Panorama Ridge cutoff it arched left towards Mount Richards, crossed the Highway and the E&N then a long trestle spanning the wetlands below Quist’s farm before climbing the other side.

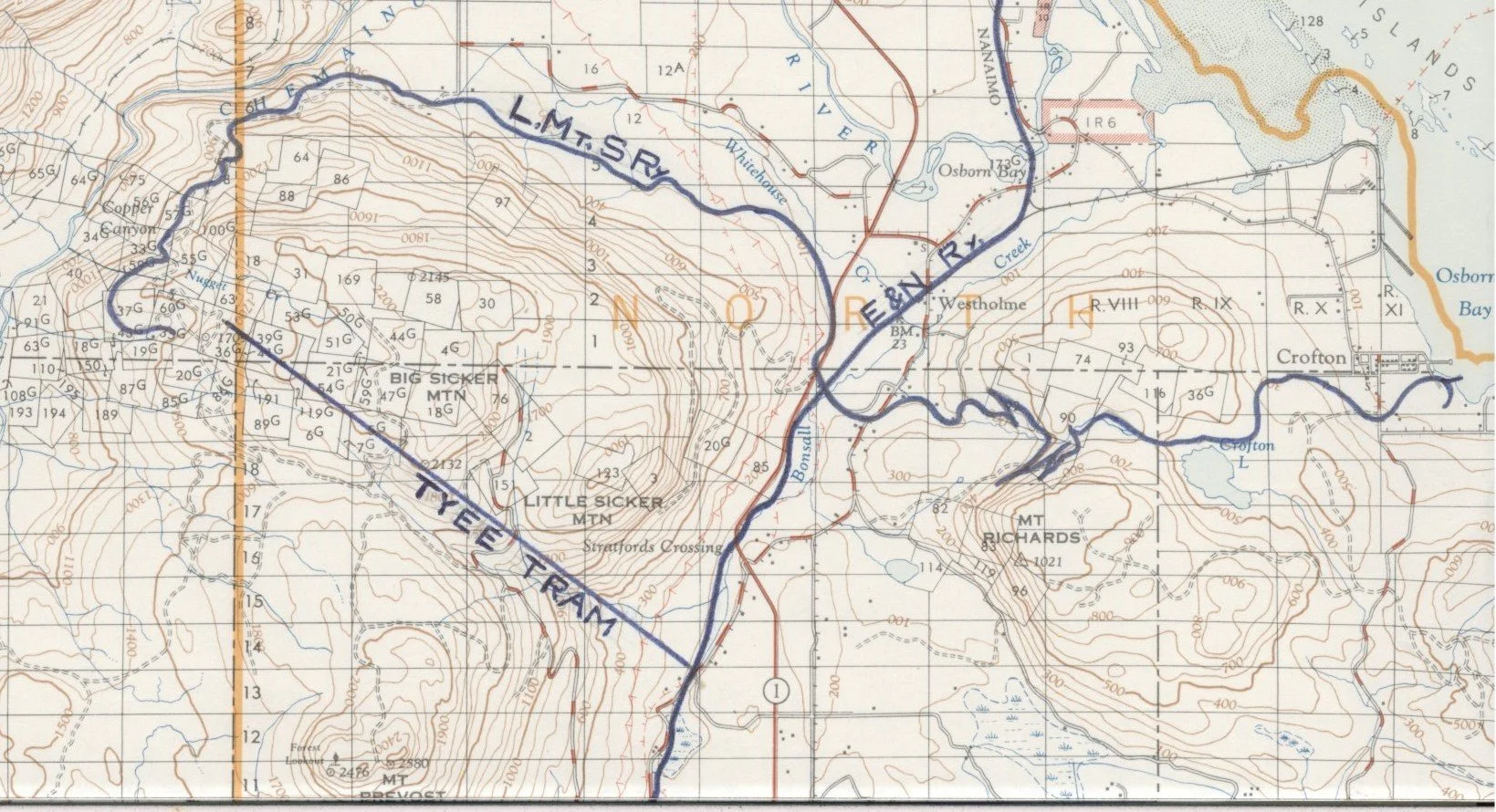

Once across today’s Westholme Road it twisted and turned (see map below) through what’s now Eves Provincial Park and skirted the northern side of Mount Richards before beginning the last miles into Crofton.

You can clearly see where the Lenora Mt. Sicker Railway, marked in blue, crossed the Trans Canada Highway and the E&N Railway. Where the serpentine narrow gauge grade seems to go suddenly mad, like a seismograph during an earthquake, are the famous Switchbacks.

Several years ago I and friends scoured both sides of the highway, looking for evidence: stretches of grade, perhaps some rock cribbing, something—anything—of the railway. Nada.

Highway construction (ca 1949-50) appears to have obliterated every visible trace. Somewhere after those three private properties where it passed through their front yards, it turned towards the northern slope of Mount Richards and crossed the wetlands while wending eastward towards salt water.

You can easily see where it reached hard ground on the other side; it’s in someone’s back yard and forms most of their driveway to Westholme Road. Then on through Eves Park as described above.

Speaking of this little gem, you’ll actually see a short length of the old railway and some photo signboards (not to mention a panoramic view of the Westholme Valley). I doubt that these rails are original to the LMSRR, however, as, according to news reports of the day, the rails were later torn up for scrap. There’s no reason to think that any were discarded here, but no matter.

—www.ehcanadatravel.com

In 2003 the Park’s directors commissioned an interpretive sign and held a ‘Last Spike’ ceremony. One of the photos displayed was courtesy of (the late) Elwood White, co-author of the book, Shays on the Switchbacks, the story of the LMSRR that he and Dave Wilkie published in the 1960s.

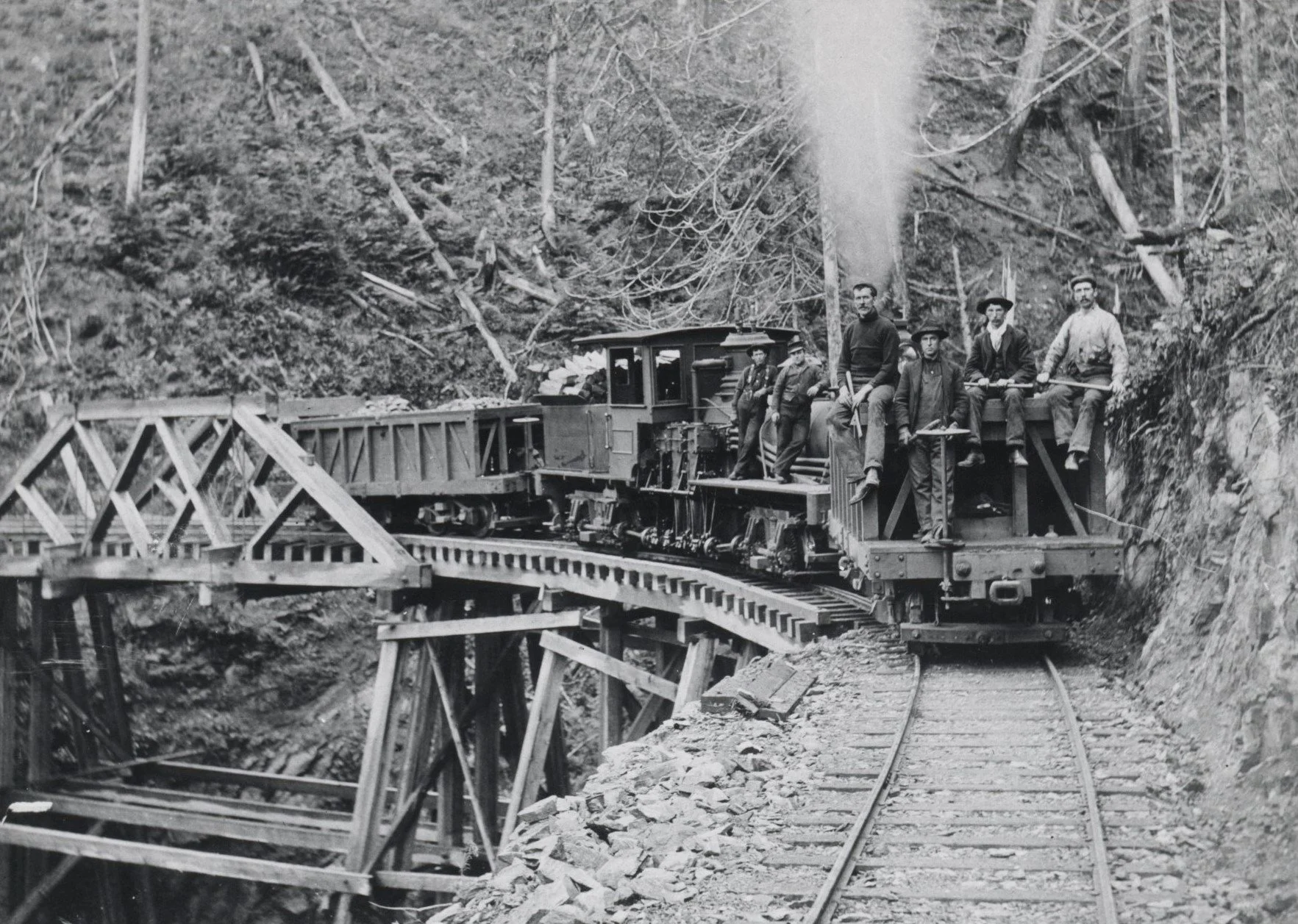

It shows the No. 2 Shay with two ore cars, crossing the trestle over Nugget Creek.

–Courtesy of Elwood White

The first car appears to be carrying construction workers. If you visit this site today you’ll be disappointed—in the overgrown creek bed, just some rotting timbers and some lengths of steel rod that held the small, single-span bridge together.

It’s hard to match today’s scene with that of yesteryear as depicted in the great photo above.

* * * * *

Which brings us to as good a point as any to tell you about the railway itself and why Henry Croft risked all to build it, before we continue to Mount Richards where the best of the existing LMSRR roadway can be found.

Briefly, as I’ve told the story of the copper mining on Mount Sicker so many times:

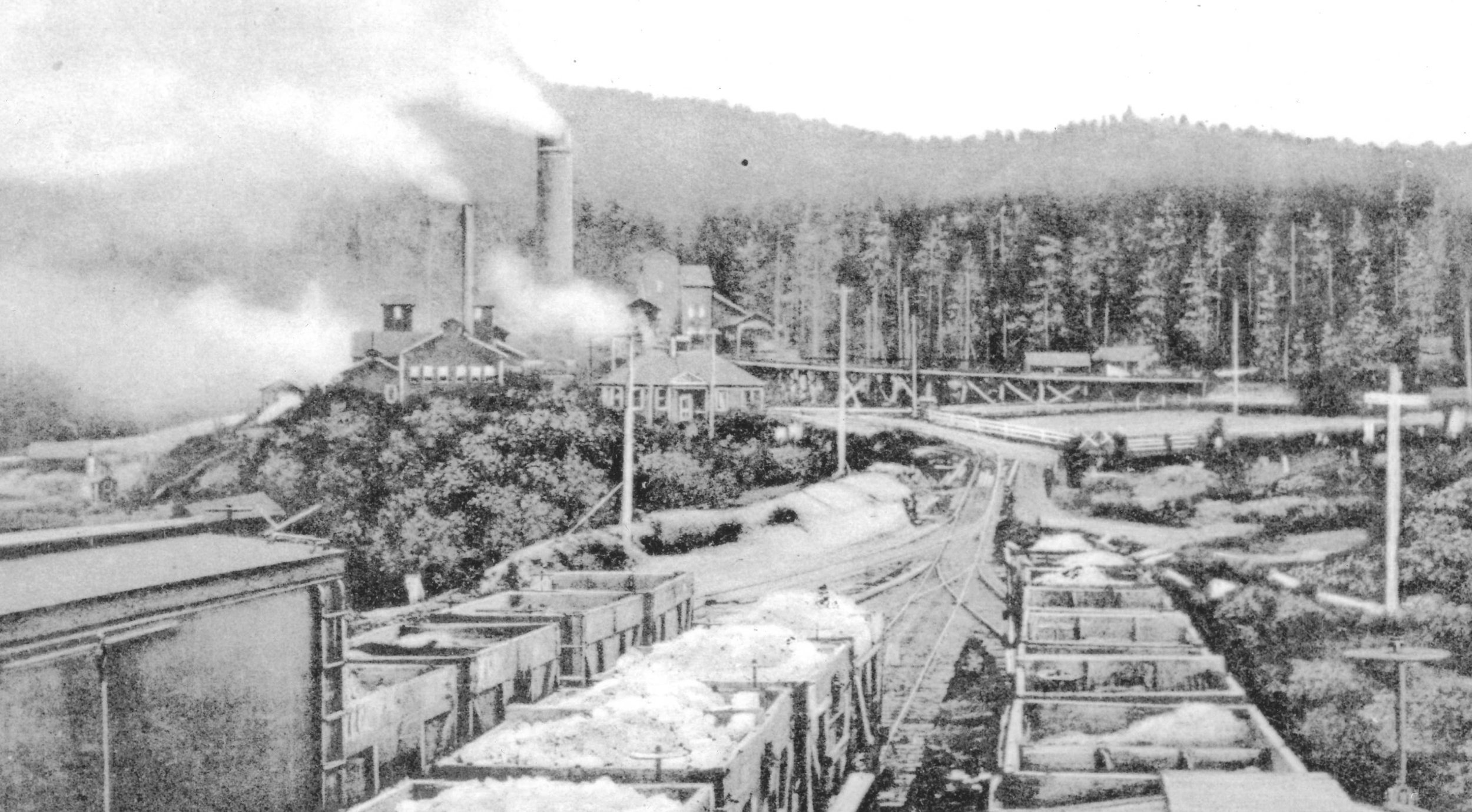

Manager of the Lenora, Mount Sicker Copper mining Co. on Mount Sicker, Henry Croft decided he needed to transport his rich copper ore, first to the E&N Railway, then to a new smelter at Crofton, the deep water port which bears his name to this day. —Courtesy of Elwood White

Heny Croft’s mine was the fourth largest shipper of ore in the province in January 1900. He’d originally tried hauling his ore down the mountain to the E&N at Mount Sicker Siding by means of a three-mile-long tramway. But, because the cars were drawn by horses and its rails were made of wood with straps of iron for bearing surfaces, the primitive system was slow and subject to repeated mechanical failure.

The ore that paid the bills began to pile up at the mine.

Hence his decision to build, at great cost, a narrow gauge railway. It was expensive because of its many curves, some of them up to 50 degrees (the Nugget Creek crossing was no less than 75 degrees) in the almost precipitous descent of the northwestern slope of Mount Sicker.

The little railway, thanks to these topographical challenges, took four months to reach the E&N mainline. This worked until Henry became convinced that E&N owner (and brother-in-law James Dunsmuir) was gouging him on freight rates to Ladysmith where, at further cost, the ore had to be transshipped to Tacoma for smelting. So he extended his own and his company’s shareholders’ necks even further by extending the line to salt water.

When all of the expenses were paid, they’re said to have totalled $60,000; you can multiply that by 25 to arrive at today’s value—an enormous sum, 125 years ago.

In Shays on the Switchback authors White and Wilkie described the railway’s first engine, a 10-ton Shay named the Lenora No. 1, as a “machine of rare beauty”. She was also small, able to handle just a single 10-ton, or two self-dumping five-ton loaded ore cars at a time.

(The reality was that she had to be small to navigate the roller-coaster right-of-way, in particular the Switchbacks on Mount Richards where she had to nose into notches carved into the mountainside, back up, nose in, back up, three times as she sought to gain elevation.)

But that was yet in the future. On Jan. 21, 1901, engineer Aaron Garland and conductor R.L. Gibbs, took the No. 1 on her first run with a load of high-grade ore down to the E&N.

Soon the LMSRR’s little No. 1 locomotive was hauling high-grade ore from the Lenora Mine. —Courtesy of Elwood White

Riding the train down the steep and twisting slope of Mount Sicker was a hair raising experience, brakemen having to ride on each of the two ore cars to apply the brakes when necessary, and to sand steeper grades for extra traction.

A daring Colonist reporter agreed to a ride on one of the cars. Having been instructed by the conductor to “hang on anywhere we could,” he did so, “as, with a warning whistle, the little engine began to push, puff and fume up the big hill to an elevation of well over a thousand feet from the starting point [at the Lenora mine]...

“As the straining ore train skirted the edge of the mighty canyon dividing Mt. Brenton and Mt. Sicker, sometimes the car was at such an angle that a chunk of ore would roll off while the tenderfoot passengers were compelled to sit on the side of the oscillating vehicle with their feet dangling over the precipice.

“If they looked while rounding the sharp curves, the tall firs skirting the Chemainus River looked like animated toothpicks moving in the mazes of some strange dance... To those unaccustomed to the hills it was out of the question to close their eyes so they just stared at the appalling immensity of nature.

“The thought occurred to everyone in the party, if the brakes had failed or become unmanageable, what a terrible trip they would have taken to eternity.”

Croft’s decision to save freight costs to distant Tacoma by treating his ores at a newly-built smelter at Crofton meant that he had to extend his railway. In its March 6, 1902 edition the Crofton Gazette confidently predicted that “trains will be running into Crofton [built to accommodate the smelter and its work force] probably before the end of the month”.

When a disgruntled James Dunsmuir denied him a level crossing of his E&N at Mount Sicker Crossing, Henry was put to the further expense of seeking a ruling from the Dominion government. Politicians and bureaucrats in Ottawa split the difference between the belligerents by allowing him to build a timber overpass. (Like much of the rest of his railway it, too, has vanished.)

He also had to buy another locomotive; for all that, by May 1902, the LMSRR was up and running daily between the Lenora Mine and Crofton, with a switch of engines at Mt. Sicker Siding.

The inauguration of the railway was a red-letter day in the words of the Crofton Gazette after a flower-bedecked train hauled a load of journalists and “mining men” from Crofton to his Mount Sicker Hotel at Lenora townsite. The Gazette proudly declared that the new railway “was the practical inauguration of a new stage of development on the Island”.

A week later, the last spike was driven at Crofton by Mrs. Croft as a crowd of dignitaries watched.

With only the last stretches of track and trestles that connected the railway to the smelter to be completed, the Gazette confidently predicted that the smelter would fire up a month later.

“The last spike has been driven on the Lenora-Mount Sicker Railway extension, and this wonderful little line now provides direct communication between the mines of Mount Sicker and district and the Crofton smelter.”

All of this, the newspaper was convinced, promised “a new stimulus, fresh developments, and a correspondingly increased output. It provides brighter hopes for prospectors...more hands at work and the certainty of the continuance of work. In a word it spells prosperity.

“To the farmer it promises new markets for his agricultural products, and to the merchant it opens an avenue of steady sale for his merchandise. To the languishing mining broker and the hard-up real estate agent it equally means business. In a word, again we repeat, it foreshadows prosperity.

“The driving of the last spike of the Lenora-Mount Sicker Railway extension on the smelter site at Crofton last week will be a memorable event in the industrial annals of the Island.”

Croft placed two larger Shay locomotives on the line, the secondhand No. 2 and the new No. 3. This was the engine that, with Al Parkinson as engineer, Albert Holman as fireman and James Porter as conductor, hauled the first train of ore to the smelter. To handle the standard gauge rail cars that utilized the barge service at the company dock in Crofton, yet a fourth locomotive had to be acquired, this one a 15-year-old standard gauge Forney.

All of this represented a magnificent achievement (not to mention expense) and all was, alas, for naught.

Both Henry Croft’s Lenora Mine and the competing Tyee Mine were working the same rich ore pocket. It was inevitable that Mount Sicker’s copper which had generated two towns, a railway, a tram line and two smelters would run out of ore, but that end came sooner than anticipated for all concerned because both mining companies were exploiting the same, limited deposit.

Probably the biggest single loser was Henry Croft, a story I’ve told in Riches to Ruin. Howe Sound’s Britannia Mines utilized the Crofton smelter and wharf for several years but the need for Henry’s mountain-defying narrow gauge railway ceased with the Lenora’s closure.

When both the Lenora and Tyee mines were reactivated during the Second World War there was no need for the LMSRR. By then the rails had long been torn up for scrap metal, the untreated ties had rotted away and all that was left was the winding right-of-way down Mount Sicker and around Mount Richards.

Without its railway tracks the abandoned line became just a country lane as it wandered through the second- and third-growth forest, other than for short stretches on both mountains which were recycled as logging roads.

From Crofton you begin at the head of Robert Street. You start out well enough as you head for and past Crofton Lake (you can find a map on Google) but you’ll then find yourself walking on a hard-packed gravel road. This is part of the grade, however; as proof, I picked a railway spike out of the gravel.

You’ll skirt Crofton Lake as you follow the old LMSRR grade.

Even with the disruptions in the railway grade, just keep bearing southwesterly, using the northern slope of Mount Richards and the not-so-distant-as-the-crow-flies Trans Canada Highway as your guides.

You’ll not mistake the entrance to the last and best stretch of the former railway grade.

Approaching the famous Switchbacks.

Mother Nature is beginning to reclaim some of Henry Croft’s railway but I still found spikes, a tie plate and drift pins from a vanished trestle.

You’ll have to be observant and use your imagination once you do reach the Switchbacks, which are, really, just gouges in the mountainside to allow the trains to shunt in and shunt out, once, twice, thrice, on their way to and from Crofton. They’ll remind you just how small (in this age of super-sized railways) Croft’s trains really were.

Immediately beyond, the grade curves gently southward towards the highway; it’s here you’ll see the rock cribbing shown in the photo at the start of this story.

But, at this point, you’re on private land; you can see the property owner’s house and you’ll probably arouse his dog. In my previous hikes of the LMSRR, this is where I’ve turned around.

Mount Sicker’s mines and two townships, Crofton’s smelter and the Lenora Mount Sicker Railway are all history now. There’s little to see after decades of repeated logging. Which makes the single length of restored LMSRR track at Eves Provincial Park, and the surviving stretches of abandoned railway grade on Mounts Sicker and Richards all the more precious.

A popular RV park now occupies of the site of the Crofton smelter.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.