HMCS Matane - From Seagoing Warrior To Rusting Corpse

She made naval history—only to die on a Vancouver Island beach.

But she hasn’t been forgotten.

* * * * *

If any Chronicles readers haven’t figured it out by now that I have a ‘thing’ for remembrance, I don’t suppose they ever will. But, I’m happy to say, I’m not alone.

Purely by chance, while shuffling files this week, I saw one I hadn’t looked at in probably 20 years: HMCS Matane. It’s a name that likely means nothing to most people. But as the son of a career RCN man who served in the North Atlantic during the Second World War, I’ve always been fascinated by Canada’s illustrious naval history.

And I have a vicarious link to this River-class frigate in that I sought her out in the 1960s to take photos of her in her final repose—on a beach just off the Island Highway some miles south of Campbell River. By then, sad to say, she was a sight to break a seaman’s heart.

What remained was just a gutted hull ravaged by time and tide; there was little to be seen of her once rakish lines, of what had been a ship of war and one of Canada’s illustrious Second World War navy—the third largest navy in the world by V-E and V-J Days.

For almost 20 years this broken hulk had served as a breakwater at Oyster Bay. By 1965, having outlived even that ignominious role, she lay, ram-rod straight, in the sand and mud. Only a faint ‘K444’ peeked through the rust to identify her as a former RCN frigate which had gallantly served our country during the World War Two.

Built by Canadian Vickers Ltd., Montreal, HMCS Matane was commissioned in the Royal Canadian Navy as the K444 on October 22, 1943, and immediately commenced a brief—but busy—naval career.

At first employed in training and anti-submarine-duties in home waters, she later joined Escort Group 9 (EG-9) as senior ship, the group comprising two frigates and four corvettes. Given a roving commission, Matane’s force was to support convoys being attacked or fearing attack. But instead of maintaining the customary protective screen around the merchantmen, EG-9 could patrol at will and fight U-boats on their own terms.

On March 1, 1944 Matane and company weighed anchor for the Western Approaches of the United Kingdom. By this time, the German submarine campaign had been concentrated in that vital area and it wasn’t long before EG-9 encountered the undersea raiders.

Loading a torpedo. U-boats were among the deadliest German weapons of the Second World War. —Wikipedia Commons

Nine days after leaving Halifax, HMC Ships Swansea and Owen Sound detected and attacked a U-Boat engaged in stalking a convoy and finally sank the German, identified as the U-845. Little more than a month later, HMCS Swansea participated in the destruction of U-448, the second kill accredited to Matane’s group.

Petty Officer G. Ardy, of London, Ontario, standing by the gun-shield on which are painted symbols indicating Swansea's U-boat kills. —Royal Navy photo

D-day, June 6, 1944 found Matane on watch at the western entrance to the English Channel. As the greatest invasion fleet in history sailed for Normandy beaches, Matane and many other Canadian and British warships patrolled the Channel against infiltrating enemy naval craft.

The ships guarding Operation Neptune proved their worth.

Only five Narvik class destroyers managed to penetrate the steel rings and one U-boat escaped after causing no damage due to the premature detonation of its acoustic torpedoes. Of the five destroyers, two were sunk, two damaged. The Invasion fleet’s western flank never again feared surface attack.

Lieut. Cdr. A.F.C. Layard and crew continued in that duty until July 20th when, stationed in the Bay of Biscay, she was hit by enemy aircraft. Immediately upon sighting the Dornier bombers the warships began a blistering fire.

But three planes, at 10,000 feet, remained just out of a range and launched several glider bombs.

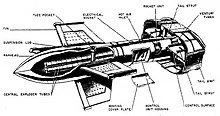

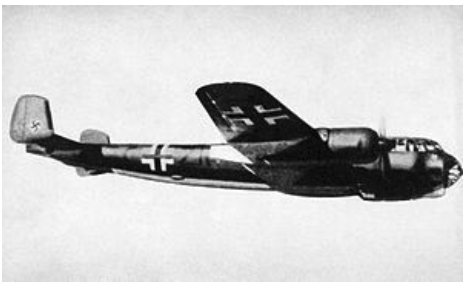

A harbinger of the missile age, this Second World War German “guided anti-ship glide bomb” was known to both Allied and German navies as “Fritz.” It was the world's first precision guided weapon deployed in combat and the first to sink a ship in combat. An armour-piercing high-explosive bomb, it was a penetration weapon intended to be used against armoured targets such as heavy cruisers and battleships, its flight path being controlled by a radio operator in the host aircraft—in Matane’s case, a Dornier Do 217K-2 bomber (below). —Wikipedia

The deadly missiles leaped ahead of the aircraft, paused, then hurtled seaward. Seconds later, one careened into the port aft side of Matane's gun deck. Miraculously, it didn't explode on contact but veered off into the sea where it erupted alongside with awesome force.

Even more remarkable was that, “if its line of flight had been six inches to the right, it would have gone down the open ammunition hoist into the magazine, and Matane would simply have disappeared from the face of the sea!”

As it was, the frigate’s thin hull was shattered, her engine room opened to the sea, her port engine shifted from its mounts. Pipes burst and clouds of steam filled the compartment, poured through the wound in her side and scalded the seamen frantically attempting to confine the flooding to the single compartment. As HMCS Swansea urgently radioed for fighter support and the other ships kept up a blistering anti-aircaft fire, HMCS Meon and HMCS Stormont crept in through the clouds of steam and secured lines to their stricken sister.

Taking turns, they towed Matane to Plymouth, the ruptured frigate managing to survive a strong gale which swept the sea that night and the following day.

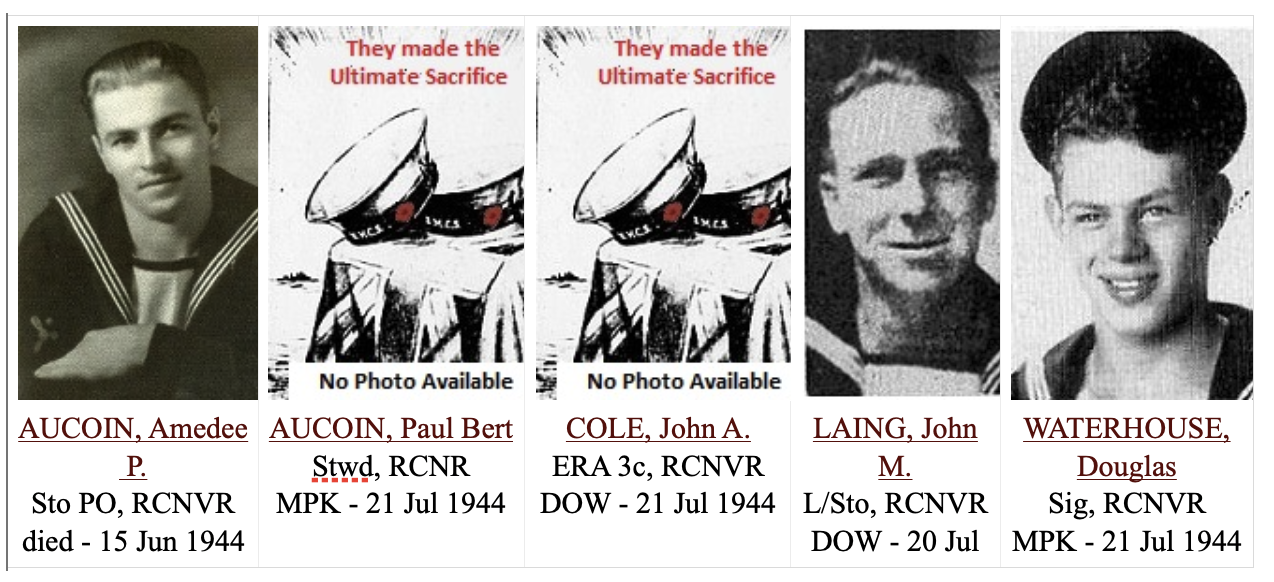

Her escape came at the cost of two men killed and two missing later declared dead: Paul Bert Aucoin, steward; John A. Cole, engine room artificer 3c, John M. Laing, Leading Stoker; and Douglas Waterhouse, signalman. All were of the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve.

Stoker Petty Officer Amadee Aucoin, left, was killed in an accident while on leave a month before his ship was hit. He wasn’t related to Paul Aucoin, steward, who was killed in the blast. How ironic that they shared the same surname and were best friends. — http://www.forposterityssake.ca/Navy/HMCS_MATANE_K444.htm

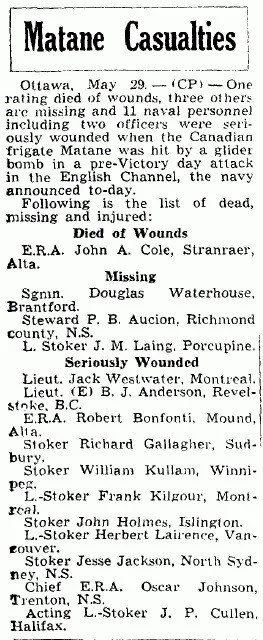

The initial list of causalities from the glider bomb attack that was published in the Hamilton Spectator, May 29, 1945. — —http://www.forposterityssake.ca/Navy/HMCS_MATANE_K444.htm

(As it happened, the Germans thought Matane had been sunk and awarded a commendation to the Dornier pilot, Lieut. Armin Garbe, who was killed less than three weeks later while attacking the Canadian destroyer HMCS St. Laurent.)

The next month, Matane was towed to Dunstaffnage, Scotland where she spent six months in refit, the repairs being completed at Londonderry. On May 7, 1945, the day before peace was declared, the frigate rejoined her sisters of EG-9. After refuelling, the ships reinforced a convoy bound for Murmansk.

The convoy encountered two U-boats about two days later. But the submarines wished to surrender. Boarding parties swarmed over the craft and they were ordered to Loch Eriboll.

On May 17th, off the Norwegian Norwegian coast, HMCS Matane received the historic surrender of 20 German ships including 15 U-boats. Aboard the armed yacht Grille was the Senior Naval Officer, Arctic and Barents Sea. When the ceremony was completed, the five surface ships were sent to Trondheim while EG-9 escorted the submarines to Loch Eriboll and Lerwick.

That done, Matane and group returned to Londonderry for the last time.

The frigate then sailed with a Gibraltar convoy until embarking homeward bound Canadian serviceman in mid-June, passing through the Panama Canal and dropping anchor in Esquimalt on July 14, 1945. Her active naval career was almost done.

After serving out of Esquimalt and Vancouver for six months, she was paid off and turned over to War Assets Corporation for disposal. With her went many other unemployed warriors.

Sold to the Victoria firm of Capital Iron and Metals Ltd., she was stripped of engines and equipment. Her battle-scarred superstructure was ripped off, leaving only her bare hull which was sold for use as part of the Oyster Bay breakwater.

(Years after, a worker at HMC Dockyard, Victoria, recalled being told of Matane’s wartime wounds by those who’d known of her real condition upon her arrival in Esquimalt. They said that, returned to active service after a rushed repair job, she’d been “literally falling to pieces”.

One of HMCS Matane’s former commanding officers, Commodore Paul D. Taylor, became CO of the Royal Canadian Naval Reserve until his retirement in July 1965. During the war, Com. Taylor won the Distinguished Cross and was mentioned in dispatches. In the Korean War he earned the US Legion of Merit.

By the mid-1960s when I visited Matane, she was a rusty corpse on a quiet beach. Unrecognized by passersby, her identity was only hinted at by the rust-smudged K444 that was still discernible. She’d yet to be demeaned as an unofficial billboard when it became a tradition of local graduating classes to announce their rite of passage on her landward flank.

C.R. Fransen, whose father helped anchor some of the 10 or more hulks that formed the Oyster Bay Breakwater, has written online of her family salvaging brass, copper lead and exotic woods from some of the wrecks, and of having caught crabs trapped in the hulls by receding tides.

Three views of poor Matane as she looked after 20-odd years in the Oyster Bay breakwater. There was no visible graffiti then. That’s the keel of another ship in the foreground. —Author’s Collection

In 1973, Campbell River Upper Islander staff writer Stephen Brewer wrote eloquently of his low-tide visit to what had become a local landmark:

“She doesn’t look much now. She hasn’t moved in years, she’s been stripped to her hull—she’s rusted and her sides have been covered with graffiti over the years. Her hull is filling with sand, her decks are gone. The coat of grey paint which once protected her from the elements is faded and chipped; only in patches can the careful observer be sure it was ever there at all.

“No one really takes much notice of her now [I have to disagree with that—TWP]. She’s just a breakwater, an abandoned hulk scuttled years ago to protect Macmillan-Bloedel’s booming grounds at Oyster Bay; a booming ground which is itself no longer in use.

“Once every few months, someone scrawls a new bit of graffiti on her side; for a few months, a fresh slogan screams at motorists speeding by on the Island Highway. ‘Jesus loves YOU,’ ‘Grads ‘71,’ ‘Peace’—all have come, seen their day, and passed on. As the paint fades, another movement comes, another slogan is added on top of its predecessor.

“And the ship, or what remains of her, bears it all with a certain stoicism, changing little if at all...”

Her fate as the last of the ships in the Oyster Bay breakwater ended violently less than a year after Brewer’s visit. In July 1974, a Victoria Daily Times headline reported, “Oyster’s Ship Blown Sky High.” This Viking’s end came as a result of concern for “safety and aesthetic reasons,” according to a Macmillan-Bloedel spokesman. Safety, because, at low tide, children were known to clamber over the hull which had been reduced by the shipbreakers and 30 years of weather and deterioration to sharp and dangerous edges.

Adding insult to injury, manager Ernie Venus said with a shrug, “This is being done as an aesthetic thing, too. It’s not a very beautiful landmark.”

It was the company’s intention, he explained, to demolish the hull to below the sand level and the remains hauled away for scrap. There was a single exception, however, a chunk of the first piece blasted was donated as a memento to the Driftwood Cafe across the highway.

Victoria Daily Times columnist Arthur Mayse who with his wife had a waterfront cabin at Oyster Bay noted her passing in print and “found it strange and more than a little ironic that [Matane] should survive the perils of North Atlantic [war]fare to be blown apart in a year of peace, in this other sea.”

So much for naval history, a gallant ship and one of the first to fall victim to a guided missile.

But, I’m pleased to report, HMCS Matane is still with us, online and in the memories of those few of her former company still living. The website I’ve given above, http://www.forposterityssake.ca/Navy/HMCS_MATANE_K444.htm, is beautifully laid out and illustrated with official and photos taken by Matane crewmembers. This website is without doubt a true labour of love and goes a long way to save Matane’s memory for posterity. In these photos she’s celebrated as one of Canada’s great fighting ladies of the Second World War—not an abandoned and abused orphan on a Vancouver Island beach.

HMCS Matane K444 (foreground) towing HMCS Springhill K323.—Courtesy the Naval Museum of Halifax