Ho! For the Leech River – Winter of Their Discontent

(Conclusion)

It’s hard to believe now, so many years and worldly experiences later, that I once was young and innocent.

I actually believed those photos I saw in the travel magazines, National Geographic, books and on TV: photos of abandoned buildings standing tall, proud and intact.

It was photos like this in American magazines that really turned me on as a kid. —www.Pinterest.com

Why, there were even dishes and cutlery on the tables as if the owners had just walked away.

Sure.

What I didn’t appreciate at that time was the sad fact that living on Vancouver Island meant that I lived in a rain forest. Meaning, need I tell you, that it rains for much of the year—dampness, mould, rot—nothing like those magazine photos of the American Southwest and the desert ghost towns that had defied time and the elements for as much as three-quarters of a century.

And this was before I learned firsthand of the all but inevitable results of decades of neglect, rain and snowfalls, fires (intentional and otherwise), industrial development, demolition, salvage and vandalism.

You can imagine my disappointment when I first set my eyes on a real ‘ghost town.’

By the early 1960''s, only the foundation and rubble remained of the once-handsome, ‘California-style bungalow’ that had been the single miners’ bunkhouse in Granby. —Author’s collection

This was the former coal mining community of Granby. It was my first of scores to follow, because I and a friend could drive right to it. It was just off the Island Highway at Cassidy. All we needed was a driver’s license and a borrowed car!

This was before I bought my first metal detector and a pickup for off-roading. But it was a promising start even though most of the buildings of this once-model company town had vanished. Happily, there were some foundations to poke about in and to take photos of for the archives that I was just starting.

No, nothing matched those magazine photos I’d pored over since I was a child, but there was enough to intrigue me and to forge my desire to explore the province and to make a career of writing about our history.

Next came historic Leechtown at the junction of the Leech and Sooke rivers. In those days this was privately owned logging territory but the gates were opened each fall for hunters and it was through a friend of a friend that I and my chums were allowed in.

Another let-down!

There, at Kennedy Flat (described in previous instalments of this series) was the site of Leechtown. The Leechtown that I’d spent hours reading about in old newspapers, and during my visits to the Provincial Archives. But where was the town?

To the eye there was—nothing!

In 1928 the British Columbia Historical Society unveiled a memorial cairn at the site of the gold commissioner’s office, Leechtown. At the time of my first visit the cairn was still there—but the bronze plaque had been stolen. —B.C Archives

Immediately nearby, a weathered cairn marked the site of the gold commissioner’s office. At least that confirmed we had the right address. There were two abandoned bulldozers that matched photos of those of the 1920’s-’40’s, some scraggly apple trees and a large log frame called a grizzly. Bu it was used for road building, not gold mining.

In a clearing just around a bend in the road, farther from the river, were two or three tumbled-down shacks and a more substantial log cabin with numerous rusting gold pans nailed to its eaves. Even a sign, identifying it as the ‘Gold Pan Cabin.’ Old Victoria newspapers used as insulation were dated in the late 1940’s.

But, according to a man we met that day who claimed to know something of the area, this cabin wasn’t from the mining era either, having been built in the 1930’s by onetime Victoria mayor Claude Harris and his hunting buddies.

Some ghost town!

During later visits, as we ventured upstream and along the Middle Fork, we found further evidences of placer mining but little in the way of cabins. An exception was the one that was not only standing but still dry inside, its shake roof having withstood how many rains and winter snows over the decades.

It obviously had had several tenants as it was originally constructed with wooden pegs then repaired with square nails and, again, with modern wire nails. Small neat piles of broken quartz showed how one of its tenants would sit on the porch in the evening, probably smoking his pipe as he cracked open the white stones with his miner’s hammer, looking for specks of gold.

He must have found some—or why the cabin and its succession of tenants?

* * * * *

Over the past few weeks I’ve told the story of the finding of colour in the Sooke and Leech rivers and the succeeding ‘rush’ that began in late July 1864. A short-lived frenzy that was fuelled by the desperation of Victoria merchants who’d struggled since the great wave of gold seekers heading for the Fraser River and Cariboo had faded away, several years before.

Last week, we left off at year’s end, with those miners who’d staked claims hunkering down for the winter. A winter, as it turned out, with deeps snows and high water levels followed by frozen ground that stalled further mining operations until well into June 1865.

(I should point out that, because of the mining laws of the day, miners had to remain with their claims; any absence greater than 72 hours and they forfeited their right to possession. So they had to hold the fort regardless of the weather and any other extremity.)

But I’m getting ahead of myself. What follows is a timeline for the year 1865, the Leech River’s last real season as a gold rush although placer mining has continued almost unabated to this day. The gold was there, 158 years ago, and it’s there today, in various amounts, and of a high carat value at a time when the price of gold has never been higher.

The trick, of course, is to find it!

When I first wrote about Leechtown in the Victoria Colonist it brought forth a man who told me how, invalided in the First World War, he’d fed his family throughout the Great Depression of the 1930’s by prospecting on the Leech River. That was 60 years after the initial stampede—and he’d still made a living by recovering Leech River gold dust and nuggets.

January 1, 1865 – Alfred Barnett, Leech River expressman, informs the Colonist that things are looking up at the diggings, the miners beginning to become active by whip-sawing lumber for making sluices and flumes. Newcomers are arriving daily and the Bacon Bar Co. is taking out good pay. Despite almost a foot of snow on the ground Bowman’s stages are still running daily between the Leech and Goldstream.

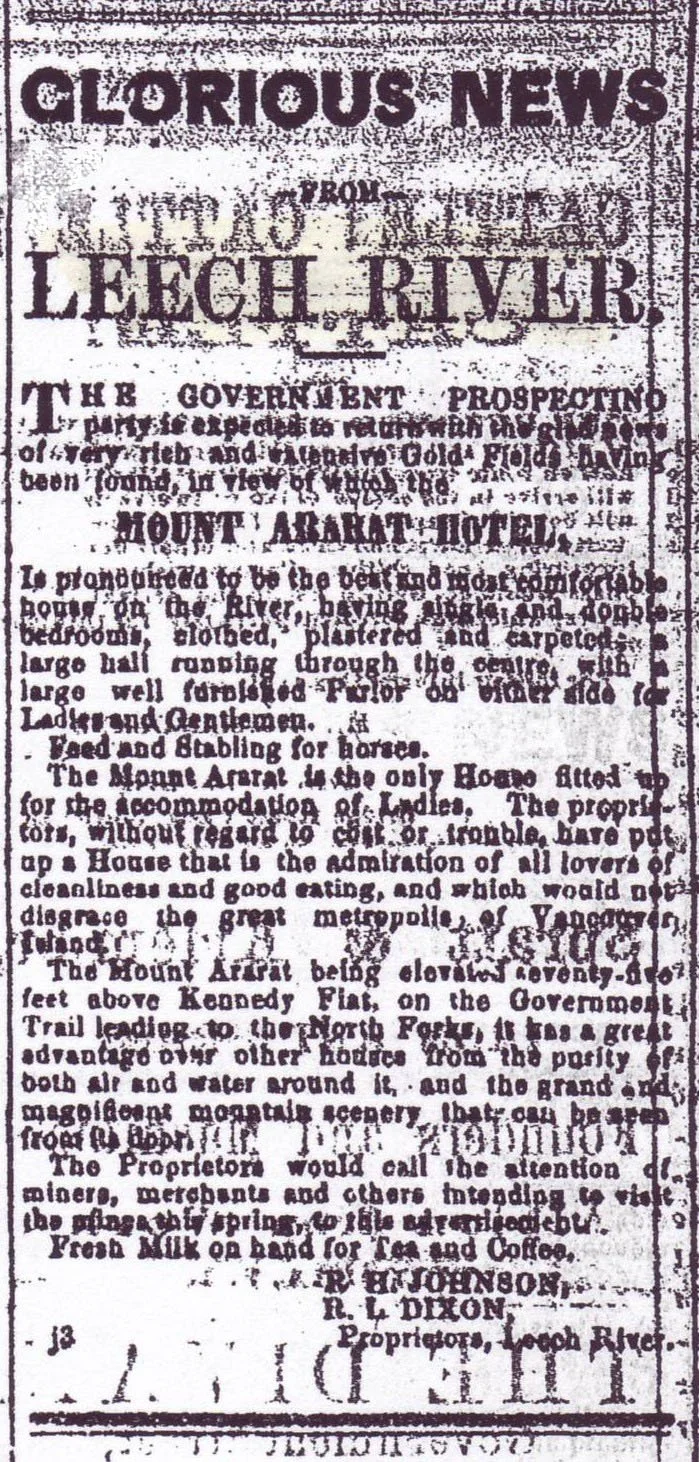

January 8 – The Colonist describes the Mount Ararat Hotel as “a most valuable addition to the mining community”. The 12-room hostelry is “admirably fitted up for the comfort and convenience of its patrons” with good beds and meals costing 50 cents each.

January 11 – A new strike at the confluence of the Sooke and Leech rivers is yielding up to $23 a day and the discovery of “considerable gold of a coarse description” from a new, undisclosed source further raises hopes.

The first birth and death occurs on the creek, the unfortunate and unidentified infant living only a few hours.

January 20 – Even a gold rush in its own backyard hadn’t reignited the Victoria economy, the Colonist glumly noting, “The general remark on the street just now is times were never so dull since 1858.” With the Leech diggings on hold until mining can resume, “the great prostrate of trade...is most severely felt...and a general feeling of insecurity and gloom” prevails.

February 10 – Things are finally looking up with new activity on Wolf Creek sparked by the discovery of a $49 nugget and rich gold-bearing quartz.

February 18 – The House of Assembly approves $1500 reward for the original discovers of the Leech River mines.

February 28 - But how the Leech diggings pale vs. those of Cariboo, it being reported that shipments of Cariboo gold to the San Francisco Mint for January alone totalled an incredible 259,930 ounces.

It certainly didn’t help that there’s three-four feet of snow on the ground at Sooke.

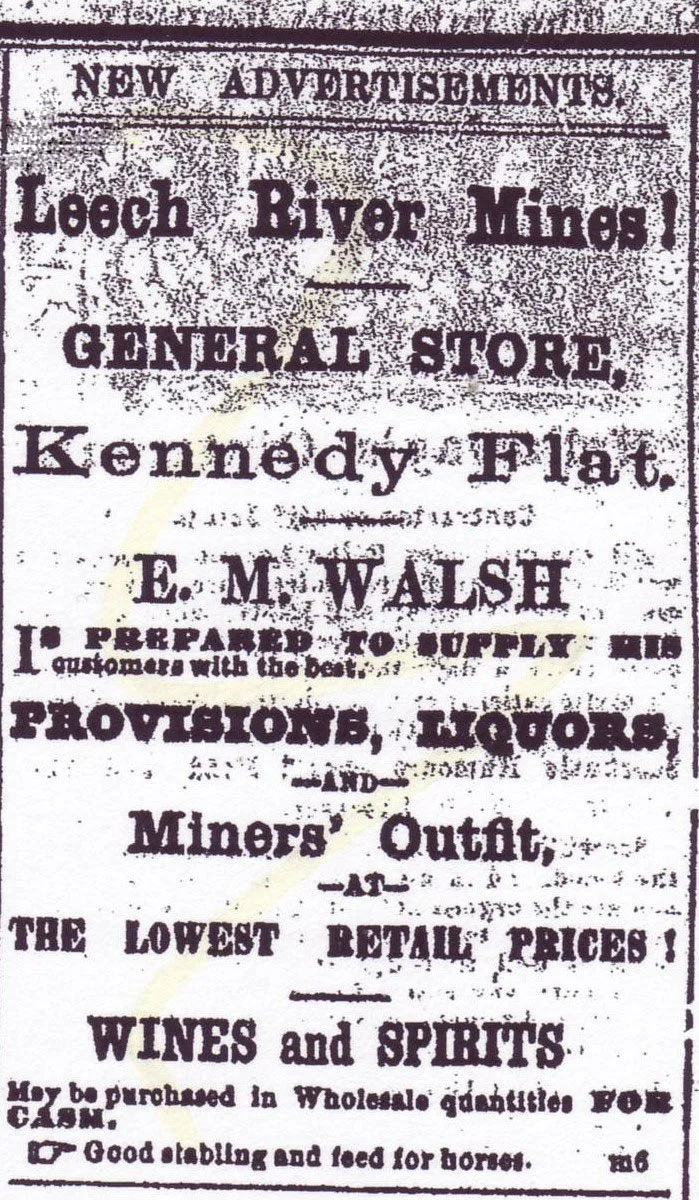

March 3 – Messrs. Moysey & Walsh purchase the Ward & Co. store on Kennedy Flat: “Every requirement of the miner will now be supplied at cheap rates.”

March 4 – “Snow now lies so deep on the trail that sleighing only goes so far as Kibblewhite’s at Goldstream.” On the positive side, a miner had offered to pay for his provisions with 30 ounces of gold.

But there’s ongoing resentment of the mining laws and a petition is sent to Colonial Gov. Kennedy to make them conform to those prevailing in the Cariboo.

His appointment as governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island was something of a demotion after his previous administrative appointments in Sierra Leone, Western Australia, Hong Kong and Queensland. His timing was off, too, the colony facing a prolonged economic downturn despite the discovery of gold in the Sooke and Leech rivers for which many, particularly the members of the hostile Legislative Assembly, held him responsible. At heart a reformer and a decent man, the former soldier left the Island post, no doubt with a sense of relief, in 1866. By then the bloom was off the rose in the Island diggings. —Wikipedia

March 19 – The snow is melting but the ground remains too hard to mine.

March 23 – The Colonist promises brighter prospects come summer but with a condition: “The Sooke mines, if properly regulated, will afford more substantial aid to the retail traders of Victoria than any other interest that has yet been discovered; but these diggings must not be neglected...”

The full-column editorial is prompted by the recall of the gold commissioner as a cost-cutting measure that leaves the miners without a local means of resolving disputes, and the “pitiful” amount of $300 that the lawmakers have allowed for mail service to the mines.

“The interests which are now centred in Sooke are too important to be imperilled by any neglect of either the Executive or the Legislature. Nothing, indeed, we feel convinced, will do more to restore confidence in Victoria and give increased value to town property than the operations at Leech River the present year.

“Every protection, therefore, and every encouragement which is in the power of the Government to bestow should be extended to our mining population...”

March 29 – Gov. Kennedy is presented with a petition bearing 200 names requesting reinstatement of a gold commissioner.

March 31 - Hopes obviously remained high at the diggings, two of the established stores on Kennedy Flat expanding their stocks and accommodations.

April 1 – The Colonist records the first death at Leech River, apparently having forgotten the infant of six weeks before. Thomas Harris was found suffering from exposure and he later died. It was thought that he would be “interred on the spot” but this isn’t likely the case.

April 4 – Proprietor Johnson of the Ararat House was “ready for all comers,” having enlarged his accommodations for human and horse patrons.

April 11 – There was an air of mystery and excitement at the diggings, it being reported that three or four men were in the habit of coming to town (Kennedy Flats aka Leechtown) after dark to buy supplies from peripheral businesses rather than frequenting the more established stores. They paid with “coarse, rusty-coloured gold.”

This, it was thought, meant they’d made a strike and efforts were made to follow them. But the mysterious strangers simply set up camp and, well provided for, told their inquisitors that they’d remain where they were indefinitely if necessary. Their disheartened followers returned to town.

A second attempt to track them in the snow, also failed.

Even more intriguing was the knowledge that one of the mystery men made a trip to Victoria to give as many as 20 friends and acquaintances a first chance to share their discovery rather than allow those already on the creeks to start a new stampede.

A Colonist informant who claimed to know one of the elusive miners said that they’d struck “extensive and very rich diggings about seven or eight miles from Kennedy Flat”.

Today we remember ‘Kennedy Flat’ at Leechtown. But it’s just a name on the maps now, there’s no trace of the E.M. Walsh store—or anything else for that matter.

April 20 – There’s talk of a new strike, this one on the Koksilah River in the Cowichan Valley.

April 29 – Former Gold Commissioner Foster is expected to resume his duties.

May 1 – The Leech River diggings now have 350 residents miners with more arriving daily, but the water is too high for any serious mining.

May 6 – The Colonist headline says it all:

GOLD EXCITEMENT.

____

A LARGE NUGGET

But—the “splendid nugget of gold” weighing over six ounces and valued at $100 isn’t from the Leech, it’s from “within a short distance of Victoria”. Popular speculation favours Wolf Creek or a Cowichan Valley stream as its secret source.

May 8 – Despite continuing high runoff from winter snows, activity is picking up and some miners are paying for their provisions with gold dust—a sure sign of improving times. It’s rumoured that the $100 nugget came from Martin’s Gulch, Leech River. WHERE?

The Colonist chides “disbelievers” who think its reported finding a hoax: “For our own part we feel not only satisfied that the golden treasure was a native production, but further believe that the locality in which it was found will turn out rich and profitable.”

May 9 – But the merchants of Victoria are still hungry; they’re planning to outfit a second exploration expedition “with a view to the discovery of gold in other localities of the Island than those known at present to exist”.

May 12 – Gov. Kennedy pays a second visit to the Leech. The miners fire a 21-gun salute in front of the Walsh store which is flying the Union Jack, specially made for the occasion by a former sailor. Then it’s off to Mount Arrarat House where a room has been reserved for him.

After a visit to the North Forks he receives an address from “a goodly muster” of the residents of Leech River. He tells them he has the greatest interest in their efforts and he’ll continue to do all he can do to help them, but the appointment of a new gold commissioner is held up in the House of Assembly.

This is followed by three rousing cheers and dinner. Next morning, he tours the camp and compliments everyone for its neatness. Another hotelier, R. Stege, shows him about his establishment and farm. Kennedy says he has authorized a new trail between Bacon Bar and the North Forks, and says he’ll return when mining operations resume full-scale.

His Excellency, says the Colonist, “holds the miner’s interest dearly at heart.”

But he doesn’t address their single greatest grievance—that they can’t “lay over their claims” for any length of time without chancing its forfeiture and re-staking by other parties. Meaning that they can’t explore for new discoveries during idle periods.

Nevertheless, the Colonist expects “to see quite as lively a time as existed here last summer in the first of the excitement”.

May 15 – Maj. George Foster is back as gold commissioner and the miners must be at their claims—or else.

May 17 – Farther afield, the latest news is, GOLD AT NOOTKA!!

May 19 – Gov. Kennedy pays Leech River again, this time with his daughters. The rivers are low.

May 20 – Heavy rain brings rising water levels—but the Spring Vale Co., for one, is earning $10-$12 per day.

June 1 – Leech River is “overrun with Chinamen [sic].”

June 5 – Visitors declare Messrs. Johnson & Dixon’s Mount Arrarat Hotel to be “as clean and comfortable a house of accommodation as can be desired... The proprietors offer special inducements to the travelling public to patronize their establishment.”

Little is happening—the creeks are again too high, thanks to continuing snow melt.

The Mount Ararat Hotel touted itself as “only House fitted for the accommodation of ladies” on the river. Not, perhaps, the best choice of words as two other “houses of accommodation” (wink, wink) had also established themselves in Leechtown!

June 16 – Despite continuing rains the rivers are falling and flume work is underway and Gov. Kennedy has sanctioned the formation of a mining board to be composed of five licensed representatives elected from Kennedy Flat, Bacon Bar and the North Forks. 85 of a total of 250 potential electors voted in what one witness described as a “most orderly style”.

June 17 – Gold Commissioner Foster holds his first court.

June 18 – A second fatality occurs at the diggings when an unnamed miner drowns in the Leech River. He is tentatively identified by a borrowed magnifying glass in his pocket as an Englishman named Grant.

As it happens, Anglican minister Rev. W.S. Reece is on hand to perform the burial service. This strongly suggests that the unfortunate miner is, in fact, buried at Leechtown which has no known cemetery.

June 20 – Flume work, sluicing and wing-damming are in high gear.

July 3 – Kennedy Flat narrowly escapes destruction from a brush fire that’s extinguished by a frantic bucket brigade.

There’s another hotel in town, this one called Rory’s. It hosts the visiting Victoria mayor Thomas Harris and his wife; the Falstaffian Harris, known for his love of food and liquor, sups until midnight.

The new hostelry, according to the Colonist, offers good accommodations for man and beast, “and all of the delicacies of the season including deer and bear meat,” superintended by Mrs. Rory who, as cusiniere en chef, is assisted by a Chinese “professor of the art”.

The mining board holds its first meeting.

July 10 – Bishop and Mrs. George Hills were in town to preach at Kennedy Flat and North Forks. As was a Rev. Mr. Browning.

July 21 – It’s full steam ahead with “not a necessarily idle man on the creek”.

July 31 – It’s reported that those miners working with rockers were earning up to $20 per day.

* * * * *

There you have it, one calendar year in the life of the Leech River gold rush.

Obviously, at the one-year mark, mining was being actively pursued. But the sad fact remains that this stampede never amounted to more than a hiccup in historical terms and, ultimately, proved to be a bitter disappointment to miners and merchants.

There were still residents living in Leechtown in the 1940’s—arguably, as late as five-six years ago when its last hold-out died and his residence was razed. No one lives there now although weekend prospectors continue to mine the Leech and neighbouring creeks.

But Vancouver Island’s hoped-for equal of mainland B.C.’s fabled Cariboo never really left the launching pad.