Is Historic Paldi About to Rise From the Ashes?

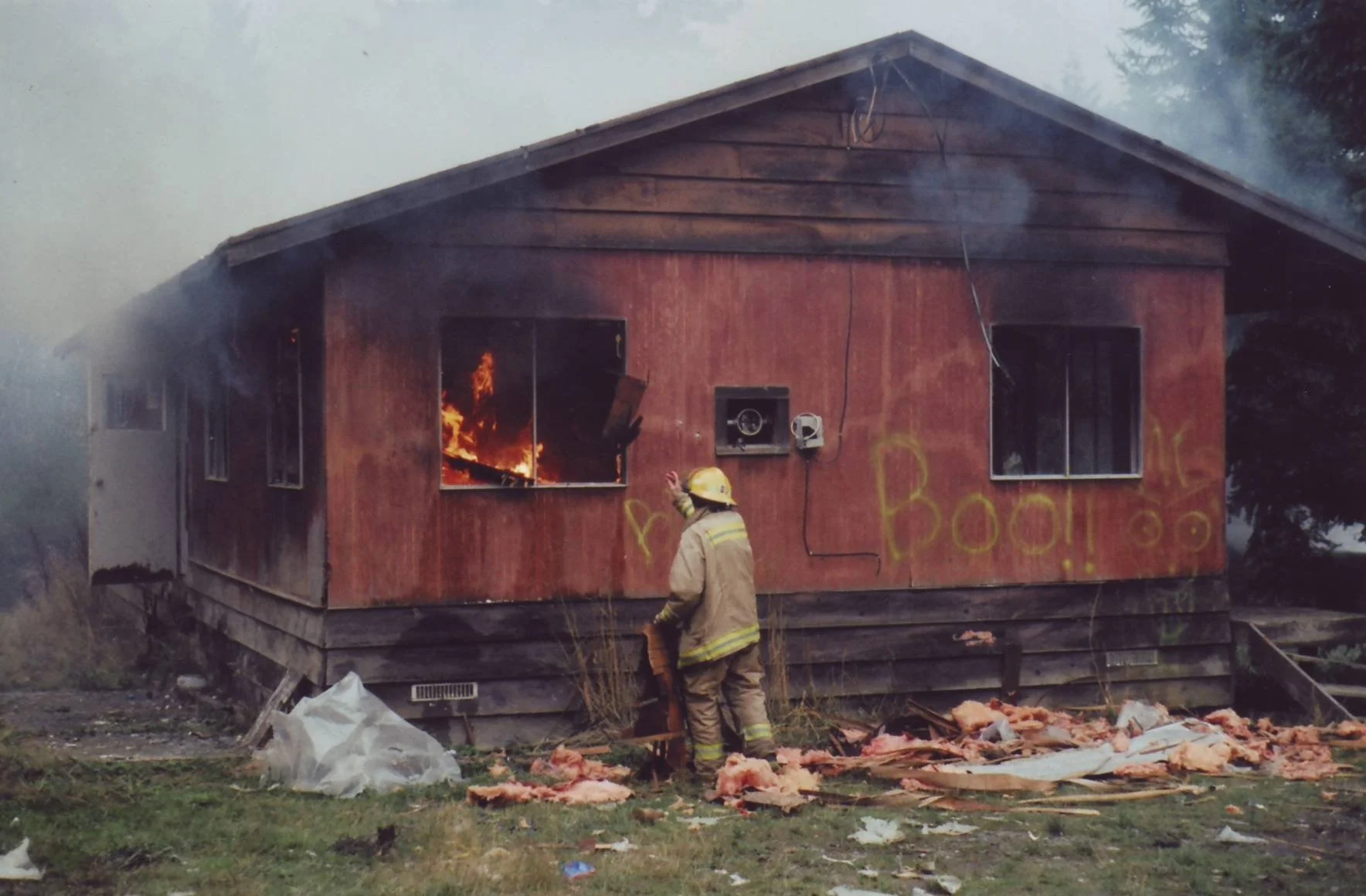

The old made way for the new in October 2005 when much of what was left of Paldi, once home to one of the largest Sikh communities in Canada, went up in flames.

In a dramatic reversal of roles the members of the Sahtlam Volunteer Fire Department hone their firefighting skills while torching the last surviving houses of Paldi, one by one.

The remains of the 88-year-old community which had housed as many as 1500 workers and residents in its heyday, were razed in preparation for a proposed 120 mixed-housing units and a re-born commercial centre.

Over three weekends regional fire departments “practice burned” a dozen old homes in the once thriving township between Duncan and Lake Cowichan. Only the second Sikh temple, built in 1959, and town founder Mayo Singh’s home (the latter only temporarily) were left standing.

That was 17 years ago. Now the building of new homes is finally underway. Existing residents and those who’ll make the reborn Paldi their home will have a rich multi-cultural heritage in the onetime sawmill town.

* * * * *

Originally known as Mayo Siding, Paldi had become a derelict shadow of its heyday when the town was famous for its harmonious blending of East Indians, Chinese, Japanese, Europeans and Canadians.

It all began with the arrival of 18-year-old Mayo Singh in California in 1904; he was following the path of his older brother Ganea and cousin Doman, who’d earlier emigrated to B.C. After brief employment with the Union Pacific Railway, Mayo, as he was known, crossed the border and eventually got work in a sawmill near Chilliwack. When the business failed, Mayo, Ganea and Doman hired 35 of the former sawmill workers to run a 16-hectare potato farm. That first attempt at operating a business in a new country ended ignominiously with the landlord’s pigs being allowed to scavenge the potatoes in lieu of outstanding rent.

That first attempt at operating a business in a new country ended ignominiously with the landlord’s pigs being allowed to scavenge the potatoes in lieu of outstanding rent.

Undaunted, the three young immigrants tried their hands at lumber milling on the Mainland, but a dwindling timber supply led them to turn their eyes to Vancouver Island. They acquired timber rights to a 24-kilometre stretch on both sides of the CPR’s Lake Cowichan Subdivision.

There was no room at the inn for the young East Indian immigrant Mayo Singh upon his arrival in Duncan. Neither of two hotels of the day, (the Tzouhalem is shown here) would rent him a room. —Author’s Collection

Sent ahead as scout, Mayo was turned away at two Duncan hotels with the suggestion that he bunk with a “Hindu man living down the tracks”. Sundher Singh not only put him up, but guided him to the prospective timber limits by railway scooter. Mayo chose a mill site between the railway line and Sahtlam Creek, and the future Paldi—named for his birthplace in India—was born. The 325 hectares were later acquired clear-title.

Over the next 30 yeas, Mayo Bros. Lumber Co. survived fires, the Great Depression and the ups and downs of the marketplace. Paldi became home to a growing population of loggers, sawmill workers and their families. At first, most families lived in tents and converted railway coaches until bunkhouses could be built. As families arrived, homes and a school sprang up around the mill.

Presiding over its steady growth was the slight, five-foot two Mayo Singh.

Still in his early 30s, but never strong after a bout with typhoid, he and business partner Kapoor Singh (for whom Sooke area’s Kapoor Regional Park is named) oversaw operations at Paldi and later at another sawmill at Sooke Lake. Mayo was empathetic to other new Canadians of all origins and made a point of hiring them at a time when racial discrimination was rampant and Canadian laws made citizenship difficult for non-whites.

Only the internment of Japanese-Canadians during the Second World War put a dent in his practice of employing ethnic minorities. (The town’s cultural centres were the Japanese community hall and the Sikh Temple, which officially opened July 1, 1919, to coincide with Dominion Day.)

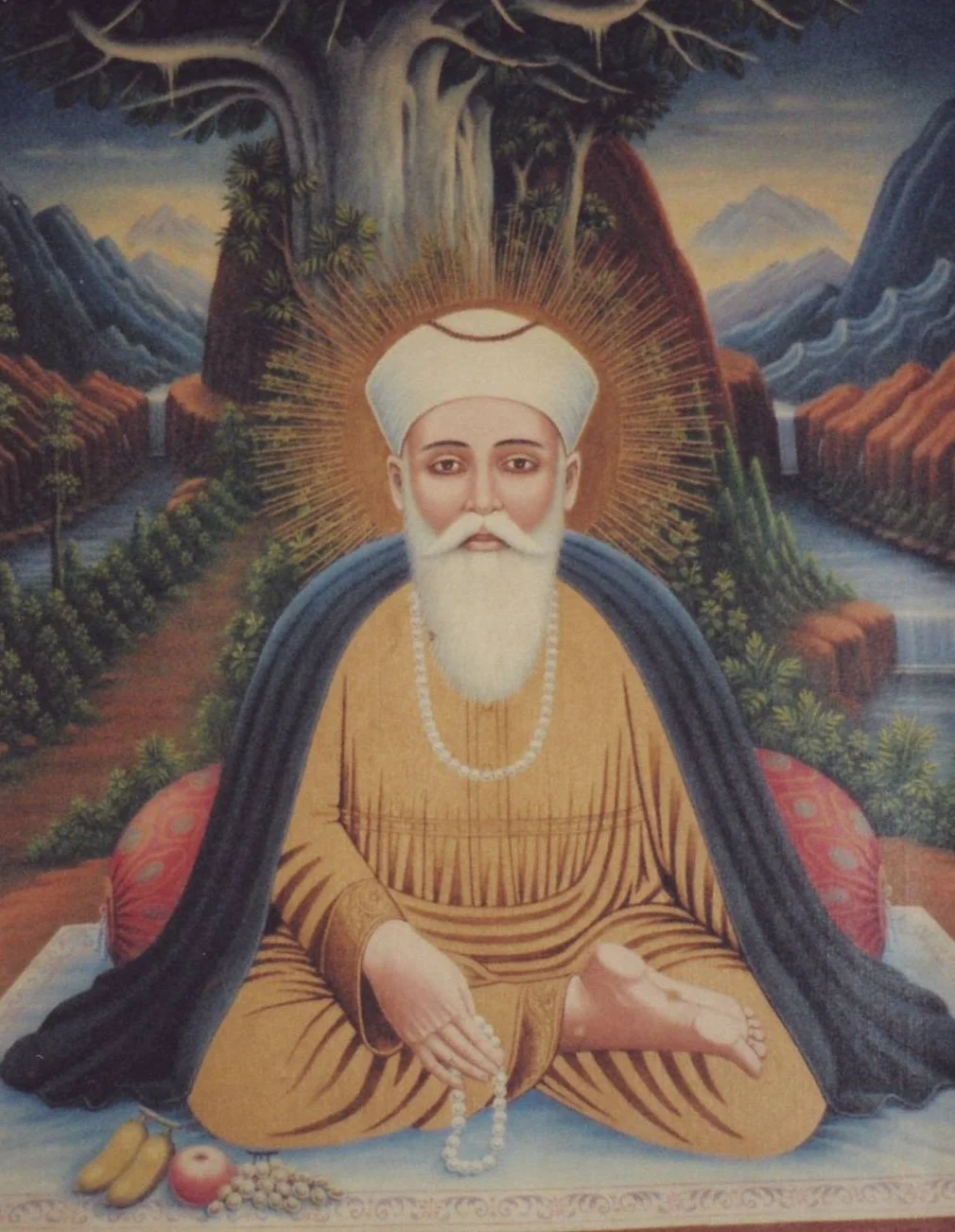

Paldi became home to the largest congregation of Sikhs yet in Canada, wrote Joan Mayo, Mayo’s daughter-in-law in her 1997 book, Paldi Remembered.

Daughter-in-law and Paldi historian Joan Mayo, the Mayo Singh house in the background, not long before its demolition by fire. —Author’s Collection

“To the East Indian men living in the bunkhouse, it hardly seemed a foreign country,” she wrote. “With the temple, store, post office and newspapers and mail from home, it was a good life. In the evenings and on the weekends, the men played soccer, volleyball and practised lifting weights and other physical sports... [It was] a close-knit community that survived in a foreign land on its own merits through love, compassion and sharing with one another.”

Three Japanese men who’d worked for Mayo on the Mainland were among Paldi’s first inhabitants, with most of the Japanese community settling to the west of the Sikh Temple. In Paldi Remembered, Sumi Kimachi recalled a happy childhood in Paldi, describing it as a harmonious miniature melting plot of Indo-, Japanese- and Chinese-Canadians, with its two temples and two company stores that stocked goods and foodstuffs imported from the old countries.

In Paldi Remembered, Tom Tagam who grew up in Paldi and died in 2004, recalled playing pranks during Jor Mallas, the Sikh religious festival. Tagam and several playmates would mix up the shoes left outside the temple.

“Then we would hide and laugh as we watched the people trying to find their shoes.”

Tagam’s sister Sumi Kimachi, then in her 80s and living in New Westminster, also recalled a happy childhood in Paldi, describing it as a harmonious miniature melting pot of new-Canadians, with its two temples and two company stores that stocked goods and foodstuffs imported from the old countries.

Across the E&N grade to the south were the Chinese, never in need of their own company store as they had access to Duncan’s Chinatown. While it may seem that Paldi was partitioned by nationality, by all accounts it was a homogeneous blessing—nothing like Duncan where all three ethnic groups were spurned by barbers and escorted to the balcony seats of the local theatre, along with First Nations peoples.

After Kapoor went his own way, Mayo and Ganea started families with wives they’d returned to India to marry. An expanding Mayo Bros. Lumber Co., which incorporated in 1914 and boasted a peak payroll of 600 employees, became a pioneer in Island railway logging.

Mayo’s most notable piece of rolling stock was a 1930 Rolls Royce Phantom II that he had mounted on railway wheels to use when he inspected his private holdings on one of the longest private railways in B.C.

The prospering sawmill owner was well-known for his beneficence. Joan Mayo notes in her book that a hospital in India and auditorium in a college near her father-in-law’s birthplace are both named for him, as is a scholarship at the University of Victoria.

Another pet project was Mill Bay’s Queen Alexandra Solarium for crippled children, which Mayo supplied with fresh fruits, vegetables, linens and sundries—”everything the...Solarium asks for,” a wholesale grocer was once quoted as saying.

The Queen Alexandra Solarium on the site of today’s Brentwood College, Mill Bay. —millbaymalahathistory.com

In 1934, it was announced that Mayo, to mark his 25 years in Canada, had made a cash donation to St. Joseph’s Hospital, where his eight children were born. (Of those eight, he lost a son to spinal meningitis and a daughter in an accidental fire.)

In the 1940s, he provided 1000 pounds of turkeys and potatoes for New Year’s staff parties at Victoria’s St. Joseph’s and Jubilee hospitals. He also supported the B.C. Protestant Orphanage and twice over the years, the Mayo Lumber Co. donated a flagpole for Beacon Hill Park.

“Mayo was regarded as a virtual Santa Claus by ore than a dozen institutions in Victoria and on the Lower Mainland,” Joan Mayo wrote in Paldi Remembered.

“None can say exactly what prompts Mayo’s generosity,” Agnes Carne Tate wrote after interviewing him for the Colonist, 76 years ago, “other than that they feel it is his ‘naturally kind nature’. His love for children, however, is the keynote of his philanthropy in the minds of many who administer his charity.”

Mayo was ably supported by his wife, Bishan Kaur, known for her welcoming line, “Come to Paldi—my husband will give your husband a job!” The first in town to own a washing machine, she shared it freely and her home served as a gathering place for East Indian women.

She died young, however—at the age of 46 in 1952. Her husband died three years later at 64. Both were cremated according to Sikh custom, their ashes interred between a bronze tablet in the family cemetery just to the northwest of Paldi town site.

One of the headstones in the private Mayo family cemetery which is between the old town site and Highway 18. —Author’s Collection

Logging operations on Hill 60, which had extended almost to Lake Cowichan, had ceased in 1943, and after a disastrous fire consumed 27 million feet of bucked timber, the Paldi mill shut down.

For a time, the old town enjoyed a baby boom, even though most of the men were commuting to company operations at Summit Lake and Nanaimo. Then residents began to move away to be closer to schools and opportunities, and Paldi became a near-ghost town, its homes rented and allowed to deteriorate.

In 1997 fire claimed the machine shop and school. With husband Rajindi and their five children, Joan Mayo had watched as flames swept the latter from existence.

A class at Mayo School in Paldi in 1938, reflecting the diverse make-up of the community. Paldi was home to families of South Asian, East Asian and European descent. —Wikipedia

“To outsiders, it was just an old building, but to anyone who has lived in Paldi, it stood as a reminder of those happier, simpler days when families of different nationalities lived, worked and played together in harmony.”

Then followed, over three weekends, the various Cowichan Valley volunteer fire departments’ systematic razing of the last remaining houses by deliberately torching them for firefighter practice.

Happily, the second Sikh Temple survives and continues as a place of worship and community as it did when Paldi was a busy township.

Joan Mayo before the second Sikh Temple, now a memorial to the Paldi of old. —Author’s Collection

Interior views of the Sikh Temple taken during an Open House in 2005.

Recently it was announced that Elk Ridge Estates is about to begin construction of what will become 350 townhouses and single family homes between Highway 18 and the former E&N Railway grade (today’s Cowichan Valley Trail) with completion scheduled for next year.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.