John Hicks Met Death on Family's Doorstep

Conclusion

So: who dun it? Readers may have drawn some conclusions of their own from the few facts ascertained by Victoria police and private parties acting unofficially as detectives in the fatal shooting of the young clerk, October 28, 1885.

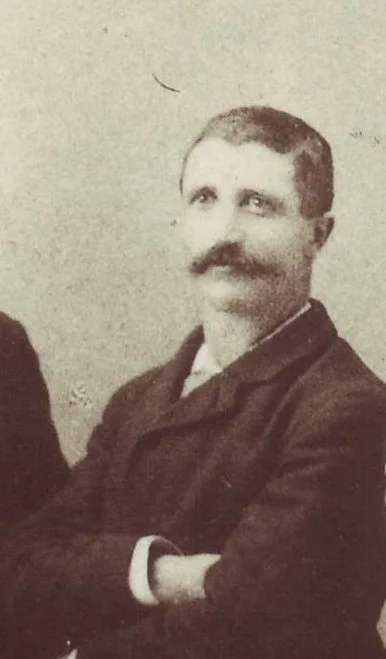

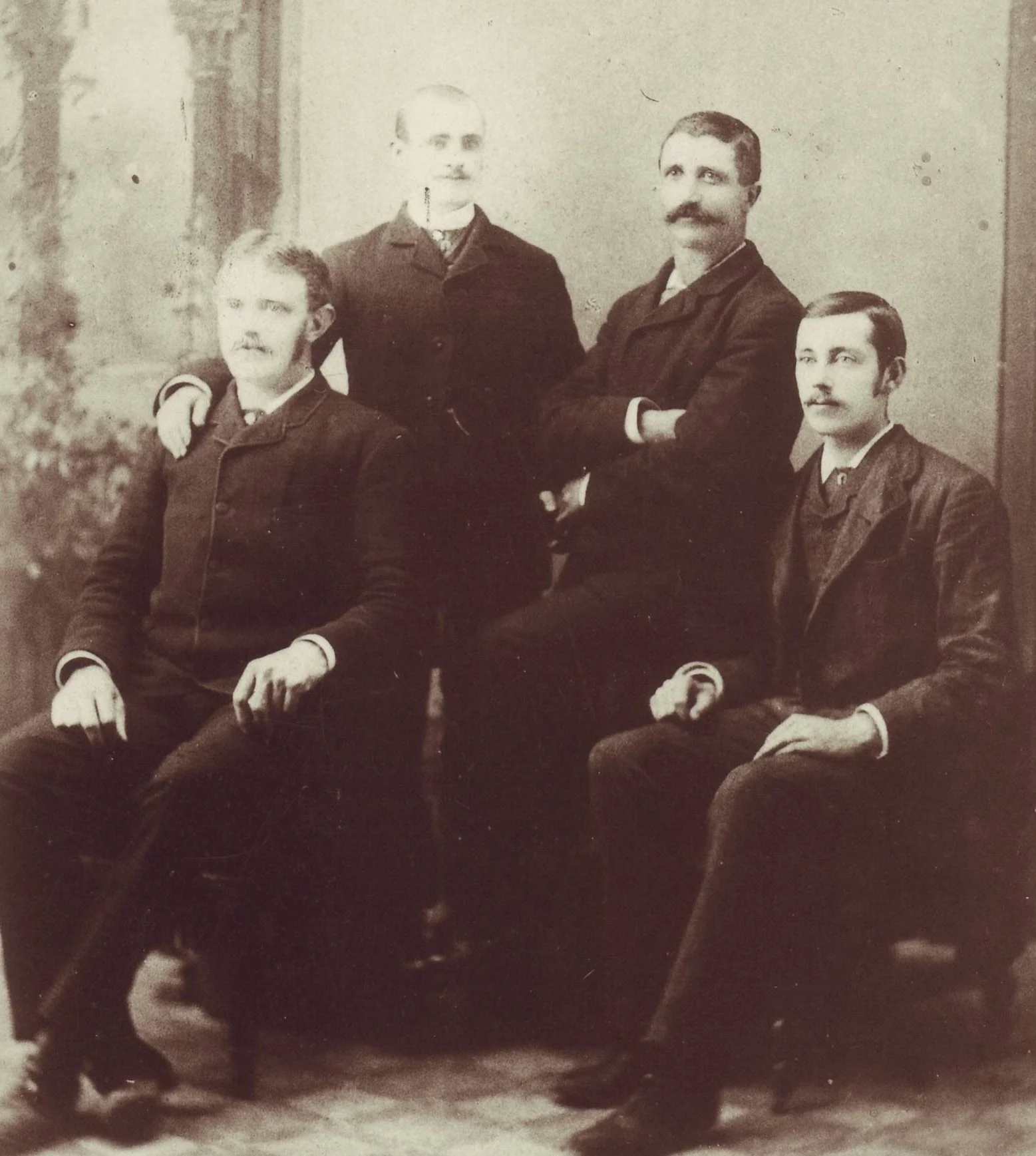

The tragic John Hicks is third from the left. —BC Archives I-8193

Let’s review the evidence: 35-year-old Hicks left the James Bay home of Capt. Hamilton Moffatt, his wife’s uncle with whom they’d been staying since their honeymoon two weeks before, to make the final arrangements for their trip to England.

Upon returning from town that evening, when within 100 feet of the Moffatt residence, he was accosted by two men.

This is what he told his father-in-law who, upon investigating gunshots and yelling, found Hicks lying in the road with a bullet in the stomach. Until his death, 36 hours later, he insisted that the robbers tried to “down” him and, as he resisted, placed a gun to his temple and fired. When the pistol ball knocked his hat from his head, Hicks dropped to the ground and they relieved him of $1800, a silver watch and a diamond stick pin.

As he lay there, the gunman fired again, this bullet entering his stomach and lodging in his back. The assailants then fled, one climbing a fence opposite the adjacent James Lascelles house and escaping through a field, the other running towards the Inner Harbour. Hicks didn’t recognize either man and he didn’t understand how they could have known that he’d made a large bank withdrawal that day.

From the start, Doctors Milne and Matthews, despite having successfully removed the bullet, doubted Hicks’s recovery.

First news of his shooting stated that a Moffatt neighbour, Mrs. Lascelles, who’d been drawn to her bedroom window by shots, had seen the assailants. However; when, interviewed at length, she told a very different and disturbing story.

As noted in last week’s Chronicle, three versions of the affair—those of the Victoria Colonist and Times and that of respected provincial historian B.A. McKelvie, while consistent overall, present some inconsistencies.

From the Colonist we learned that, as an invalid, Mrs. Lascelles had retired early to her upstairs bedroom but couldn’t sleep and raised her blind to gaze into the street before returning to bed. “About 10 o’clock...a bright flash was reflected on the bedroom wall. Thinking it was...lightning, I listened for the thunder, but instead heard a most unearthly scream, as if from some person in mortal agony... I also heard a report of a pistol.”

She woke her husband. After a second shot and more screaming she ran to the window: “The light was dim, but I could distinctly see a tall man, wearing an overcoat, walking on the grass at the side of the road. He was coming pretty fast and going towards Capt. Moffatt’s. He was uttering the same unearthly screams [and] walking unsteadily, as if he had been hurt.

“When he got opposite my window there was another flash. I saw it as plain as day. It seemed to come from his own hand. Then he fell forward on his face, got up again and walked in a half-bent position for a short distance. There was another flash, and a report, and he fell again.”

So much for the two highwaymen if we are to believe Mrs. Lascelles.

Again from the Colonist: Next morning, 40 feet from where Hicks was found, her husband, playing detective, discovered an almost new and apparently bloodstained British Bulldog pistol with four fired cartridges in its five chambers. Nearby lay an empty buckskin ‘poke’ such as prospectors used for gold dust, letters addressed to Hicks, and his hat which smelled strongly of gunpowder. It had been punctured by a ball which had entered the crown at the back and passed out through the front.

Police found no signs of foot traffic in an adjacent field although a nearby fence showed signs of having recently been scaled.

Investigation in town was even more mystifying.

Hicks had claimed to have been robbed of $1800, his watch and diamond pin, but police determined that the unemployed newlywed had no account with any city bank and he hadn’t purchased passage to England the next day as he also claimed. (Hicks said he’d carried the money on him since leaving the Old Country.)

The only support for his story came from a cab driver who, when driving him in town that day, had seen two suspicious men watching his hack and had reported them to the police.

Hence the start of rumours that Hicks had staged his own shooting to cover a lack of funds and his inability to meet the obligations of his new marriage.

John Hicks who’d denied owning a gun, could say no more as, 36 hours after he was shot–by whomever and under whatever circumstances–he died at the Moffatt home.

It was there, that same afternoon, that Capt. Moffatt told a coroner’s jury that it hadn’t taken him more than two minutes to reach the side of a man lying beside the road. Only then had he realized it was Hicks and a neighbour named Copeland had helped him carry Hicks to his home.

Although very excited, Hicks spoke coherently and appeared to be sober. Moffatt, who’d heard only two shots, hadn’t heard anyone running away, and had noted that that both Hicks’s hat and vest were powder-burned.

He described Hicks as being of a “remarkably quiet disposition and very temperate,” who’d always given him the impression of having money. He did express his amazement, however, that Hicks–or anyone–would be so foolish as to carry almost $2000 about with him.

Medical testimony showed that the fatal bullet had entered “in a place which would necessitate the muzzle having been put inside the vest, supposing the latter to have been buttoned”.

Moffatt also said that when he’d given police Sgt. Bloomfield what was believed to be the murder weapon which was found the next morning, “some 70 feet from the centre of the road”.

Copland, Moffatt’s neighbour, testified that, shortly before 10 p.m., Wednesday evening, he’d heard two shots and seen three flashes followed by the cry, “Murder!” He’d helped to carry Hicks to the Moffatt house.

He hadn’t seen or heard anyone else.

Thomas Irving then added to the mystery when he testified that he’d heard shots and seen a man who made an obvious effort to conceal his identity.

At this point, Coroner Johnson advised the jury that, in his opinion, they’d be wise to defer judgment for a few days so as to allow them the opportunity of reviewing further evidence. “It was perfectly incredible,” he thought, that Hicks, a young man of good reputation without apparent reason to take his own life, had been found in a public street, mortally wounded by a gunshot and maintaining that he’d been waylaid by two robbers.

The jury agreed to a week’s adjournment.

Two days later, funeral services for the late John Hicks were held at the Capt. Moffatt residence under the auspices of the Reformed Espiscopal Church.

When the inquest resumed, Charles Braund who claimed to have been an intimate friend of the deceased, testified to having accompanied Hicks to the skating rink that evening after Hicks had exchanged a $20 gold piece. Having known him since his arrival from England, two years before, he rated Hicks as having been “honourable, truthful....punctual and methodical in his habits”.

While skating, Hicks had said that he had to see a Mr. Spencer at the Oriental Hotel and went off in a hack, returning 20 minutes later.

Earlier that evening, Hicks had bought a large secondhand trunk and had spent all of 50 cents during their evening out. He’d never known Hicks to be depressed and, upon their parting, he’d been in his “usual good health and spirits;” having had two drinks during the course of the evening (his 50 cents’ expenditure).

W.C. Ward, manager of the Bank of British Columbia, explained that Hicks had cashed a $25 postal order at his bank some days before his death, and said that, contrary to Hicks’s deathbed deposition, it would have been virtually impossible for him to have obtained $1600 in Bank of B.C. notes in London, Eng.

Shown Hicks’s buckskin purse, Ward offered it as his opinion that $200 in gold coins and possibly $15-1600 in 50-dollar notes could be stuffed into the poke although it would have been exceedingly uncomfortable to carry it in a hip pocket.

A Bulldog revolver such as the one that killed John Hicks. —Wikipedia

Police Superintendent Bloomfield outlined the investigation to date, also noting that four shots had been fired from the Bulldog revolver which was of English make. Because the ammunition used had been of American manufacture, the slightly smaller bullet casings had split when fired. He also said that outgoing steamships were being checked for suspicious characters, a standard police tactic of the day.

John Hicks’s dying deposition was read to the jury. By its disjointed nature towards the end, he obviously was replying to questions put to him, likely by the police.

“I was shot last evening somewhere between between nine and 10 in the evening in the street [Oswego] running from the harbour past this house... I only remember the features of one of the men who did it. I was...walking in the middle of the street when I saw two men coming across my path on the cross street. I was a little in advance of them.

“They were walking together. The first thing I remember was my hat was blown off my head by, I suppose, a bullet, because I heard a report of firearms. The men were then behind me. I cannot say how near—say 10 yards. I turned round and one of them seized me by the throat and necktie.

“He drew the necktie tight, nearly choking me, so that I could not speak distinctly, and the other or both together threw me [down]. One of them then commenced to rifle my pockets. I said, ‘For God’s sake, spare my life,’ but he still went on turning my pockets inside out while the other held me.

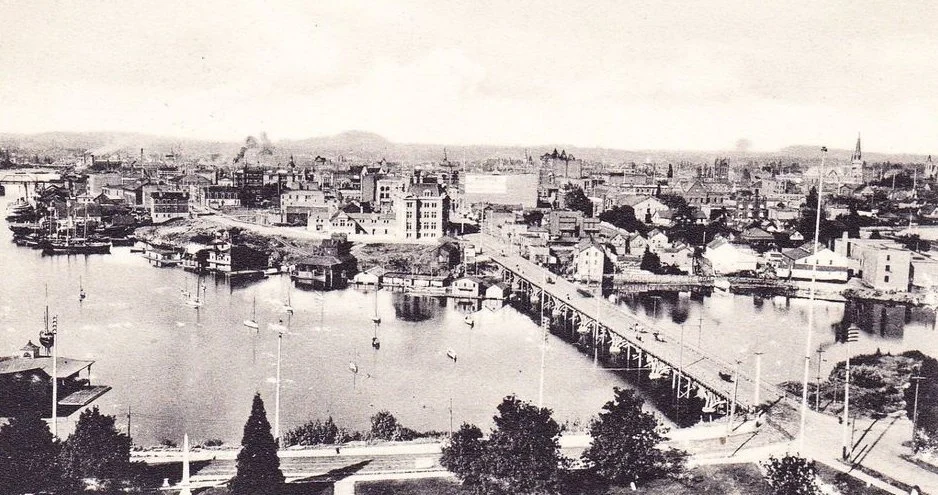

Victoria’s James Bay-Inner Harbour as it looked about 20 years after John Hicks was fatally wounded on Oswego Street. Hicks said that one of his two attackers ran off towards the harbour. —Author’s collection

“I struggled then I heard another shot fired close to me, but I did not feel anything.

“I was powerless in their hands. I cried out “Murder!” at the top of my voice. They said something to each other but I could not catch what it was.

“While I was struggling I saw something glisten. I knew what it was; it was a pistol. It was in the shortest man’s hand. He fired, and I think I rolled on my side. He was standing over me, and the pistol could not have been many inches from me; it was right over my stomach.

“After that shot I distinctly saw him make for the fence, and the other man, as well as I could tell, ran down the street towards the harbour. The tall man was almost my build with a black moustache. I do not remember ever seeing him before. I suppose he was middle-aged; as well as I could judge he had darkish clothes.

“I could not see the face of the short man. I could not say whether they unbuttoned my clothes but I think they unbuttoned my vest.

“I always carry my papers in the inside pocket of my coat. They took from my pants pocket behind a chamois leather purse. Roughly speaking, there were from $1800 to $2000 in the purse. It was in gold $20 pieces and notes, I think about $200 gold, and the rest Bank of British Columbia notes.

“The greatest part of it was in my possession from April last; I brought it from the Old Country. I got both the gold and the notes in England. I have received one small draft and some post office orders since I came to this country. I cashed a post office order the other morning. I had a silver stem-winding watch on me with a half hunter case [folding cover].

“I don’t think I was wearing a scarf pin because I had a tie with a knot. I had on a pair of gold sleeve links and a gold collar stud, plain gold. I never let anybody know what money I had. I came up past the drill shed and turned round Tiedemann’s corner, on my way from town.

“There was not a word before the man fired. As soon as the man had fired into my stomach he ran away. That was the shot that wounded me.

“I went to the skating rink about a quarter to nine last evening to meet a friend who had sent me a wedding present, and he walked with me as far as Fort and Government streets. This was Charles Braund who is in Mr. Morton’s book store. We went into the saloon at the corner of Fort and Government streets and had a Scotch whisky. Then we went to the Oriental [Hotel, lower Yaes Street] and parted just outside the restaurant. We also went into the Grotto Saloon [Government Street] after coming from the rink earlier in the evening.

“The majority of the notes were $50 notes.”

(Signed) John Hicks.

Sworn before E. Johnson, P.M.

John Hicks’s widow, Mary. —BC Archives 6-07871

When Mary Hicks took the witness stand it was to state that she knew nothing of her husband’s finances. She’d seen him with a purse similar to that produced at the inquest and, “frequently, he had money in it,” both gold coins and banknotes, although she didn’t know how much. She’d seen him pull “quite a number of notes” from his purse and “there was also gold in the purse”.

She didn’t know how he could have had a gun without her knowledge.

They’d been married for just three weeks after honeymooning in Oregon. On the eve of their departure for England, he’d admitted to being slightly depressed, telling her, “We have both got the blues because we are going away.”

She said she was sure that he was ill although he hadn’t complained.

In answer to a juryman, she replied that, while on their honeymoon, he’d always had money which he carried in a small pocket book but she didn’t know how much was in it.

Hicks’s former employer, Thomas Earle, stated that he had the impression that Hicks couldn’t have been too well off as Hicks had told him that he had to work for a living to support himself.

J. Judson Young described an unsuccessful search for footprints in the field next to Hicks’s shooting.

Recalled to the stand, Capt. Moffatt said he’d found a set of gold cuff links (Hicks had said he was wearing gold cuff links when robbed) in Hicks’s valise. He then complained that a “memorandum” found near “where the scuffle was supposed to have taken place” had been removed from his home without his knowledge or consent.

Note his choice of words, “supposed to...” The memorandum, written by Hicks in pencil, lists the costs of the forthcoming trip to England.

Interjected Supt. Bloomfield: “You don’t object to its being introduced, do you?”

Moffatt: “No, but to the manner in which it was obtained. It was left with me; not perhaps exactly in my charge, but being in my house, the care of it devolved upon me, and I now find that it was, as I may say, feloniously abstracted from my house.”

B.C. Provincial Police Supt. Roycroft, who’d personally assisted City police officers in the investigation, heatedly interjected, “Your honour, I object to that expression, it is entirely unwarranted, and—“

Coroner: “Well, Mr. Roycroft, it is a matter we are not dealing with right now.”

Roycroft: “No, but it is a slur upon me, and was intended for me.”

Capt. Moffatt, in a loud voice: “I beg your pardon, sir!”

Roycroft; “You maintained that the paper was taken surreptitiously.”

Coroner: “The witness [Moffatt] says he does not know who took it.”

Roycroft: “No, his manner of allusion is offensive and calculated to leave an erroneous impression on the minds of the jury which I can explain in a moment. I asked Mrs. Hicks at the house if she knew of any memorandum that deceased had made. She said, ‘Yes,’ and ran upstairs and fetched the paper produced, saying that I could take it, which I accordingly did.”

Coroner: “That is a perfectly satisfactory explanation.”

Moffatt: “Yes, that is perfectly satisfactory.”

Back on course, the Coroner thought it time for another pause: “It seems to me that the matter is more mysterious than ever...I confess I am no nearer at arriving at a conclusion than I was before, and if an adjournment will aid the arrival at a proper decision, I have no objection to offer to such a postponement.”

Foreman Yates agreed; better, he said, to await a reply to the letter that had been posted to Hicks’s relatives in England which, if it helped to clear up the mystery of his personal finances, might confirm “murder or suicide”.

It was agreed to adjourn until December 7th. When the inquest resumed a month later without, apparently, contact from England, the Colonist expressed a most unusual viewpoint, beginning with: “The public will be more than pleased at the outcome of the inquest in the matter of the Hicks tragedy.”

Why should anyone be pleased? Because the jury had ruled that the bullet that killed John Hicks had been self-inflicted, without an intention to take his own life, rather than by an assassin.

The jury had arrived at their verdict on two counts. Firstly, they’d accepted Mrs. Lascelle’s graphic eyewitness account of seeing Hicks shooting himself. Secondly, measurements taken by Superintendent Roycroft between where Hicks had lain wounded, and where the gun was found, indicated that “the wounded man could have easily thrown the weapon there”.

Then there was that third damning factor, the deceased’s claim to having been robbed of a large sum of money. The evidence (other than Mrs. Hicks’s testimony to the contrary) indicated he’d had little, not enough, apparently, to buy railway and steamer tickets to England.

Hence their verdict that John Hicks unintentionally caused his own death by a pistol shot fired during a staged robbery to cover up the fact he was all but broke and without a job.

The Colonist wasn’t finished in its interpretation of the tragedy: “The verdict re-establishes the fair fame of our city and shows it does not harbour in its midst blood-thirsty villains who first shoot down then rob an unsuspecting wayfarer.”

Finally, in a more charitable vein, “Hicks’s motive for creating a ‘sensation’ will be forever unknown. We prefer to believe that he became temporarily insane by the contemplation of the approaching expose of his necessitous circumstances, and fired the shots while in a state of mind which rendered him irresponsible for his acts.”

But the mystery of John Hicks’s death didn’t end there. Two weeks after the coroner rendered its verdict of inadvertent suicide, Capt. Moffatt received a letter from Hicks’s brother-in-law, G.M. Jenkings, in England. Jenkings expressed his and other family members’ shock at the news and refuted the jury’s verdict.

“...To me, the most terrible feature in the newspaper records, is the (as I consider) utterly untenable theory of suicide, which my knowledge of the deceased enables me to feel I may look upon as preposterous.

“He would be the last man to destroy himself, even were his pecuniary circumstances at a low ebb, a state of things for which there is not, so far as I know, the slightest reason to think he had drifted into...”

(Here, the Colonist noted that Mr. Jenkings’ had enclosed a letter from Hicks, written to his wife, Hicks’s sister, on October 26th, the day before his “cruel end”.)

Referring to the letter, Jenkings continued: “It is in a very cheerful vein and would indicate the very opposite of a suicidal tendency. As regards his means, I distinctly recall the night before his departure. Having purchased his ticket through to Victoria, he had exchanged a considerable amount of English money into notes of a description which I presume he considered suitable for his purpose.

“I do not remember what description of notes they were nor can I state any amount, but I clearly recall the fact that he showed my wife, children and self a considerable number of notes as curiosities to us, although of course, natural delicacy of feeling would prevent the acquirement on the part of any others of any accurate idea as to the amount. My impression was that it represented a considerable sum.

“Whatever conclusion the jury in Victoria arrived at, all those who knew and loved poor John Hicks in England (and they are very many) will feel quite sure that he was foully murdered.

“It is a blow to us in England from far, far away, but it has stricken many a heart here who only knew John Hicks as one of the kindest and best of men, ever ready to do a good action, ever willing to help and render aid to others, and always thinking last of himself.”

Historian B.A. McKelvie, previously cited, added a new twist: Hicks told his friend Charles Braund that he hadn’t bought the tickets to New York that day as planned, having decided, instead, in McKelvie’s words, to “wait until they had decided what amount of baggage they would have.”

McKelvie had noted other pertinent facts not covered in either of the Victoria newspaper accounts, quoting Dr. G.L. Milne who’d attended Hicks: “I last saw him at 7 a.m.; he was in a dying condition. The night before last, about 12 o’clock, I asked him some questions about the affair. He said he had never been in the habit of carrying a revolver and laughed at the idea of his doing himself any harm. At that time, I had told him that the case was hopeless. I saw no sign of mental aberration.”

And John Richards: “I was with him from 9 till about 3 of his last night alive—and was there when Dr. Milne visited him. I asked him if he shot himself. He said, ‘No—no, Mr. Richards.’

“...I asked him if he ever had a revolver. He said, ‘Never since I left the Cape [South Africa].’ I asked him if he had confessed to Bishop Cridge that he had shot himself. He said, ‘No’—and he never did. When I left I shook hands with him, saying I would rest assured that he never committed the deed. He said, ‘I never did, I never owned a revolver since I left the Cape.’”

* * * * *

Did John Hicks really fake his own shooting to hide the fact he was broke and had, in fact, wed under false pretenses? Or was he, as he declared in his dying breath, the victim of robbery and murder?

Today’s medical science would, no doubt, answer that question quickly—it probably would be able to save his life, too. Instead, we have to work with circumstantial evidence and, most damning of all, Mrs. Lascelles’s testimony, somewhat contradictory as it is in the differing reports:

That she’d watched from her window as he fired, not once but twice (most witnesses agreed there were four shots in all), shooting himself in the stomach which seems such an improbable choice of target even if he’d had suicide in mind. And would he have gone to such bizarre lengths to cover his suicide?

Had he really come to Victoria with money from the Old Country? Did he court and wed Mary Blenkinsop when he was broke? Or was he, as he declared with his dying breath, the victim of robbery and murder?

A witness at the inquest testified that, contrary to Mrs. Lascelles’s statement, the street light hadn’t been on, and another agreed it had been very dark. Thomas Irving said that, while investigating shots and the cries of “Murder!” he’d “met a man with a moustache. He was walking slowly on the sidewalk and turned a little to let us go by. When he got close to us he dropped his head down into his overcoat to hide his face.”

Rightly or wrongly, his widow and in-laws passed their own, ultimate, verdict when they had him interred in Ross Bay Cemetery. John Hicks is there today–but he’s not in the family’s plot.

Hopefully, John Hicks has found peace in beautiful Ross Bay Cemetery even though he’s separated from all who knew and cared for him.—www.tripadvisor.ca

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.