John Hicks Met Death on Family's Doorstep

Part 1

Police surmised that his attackers ‘dogged’ him for hours, awaiting their chance.

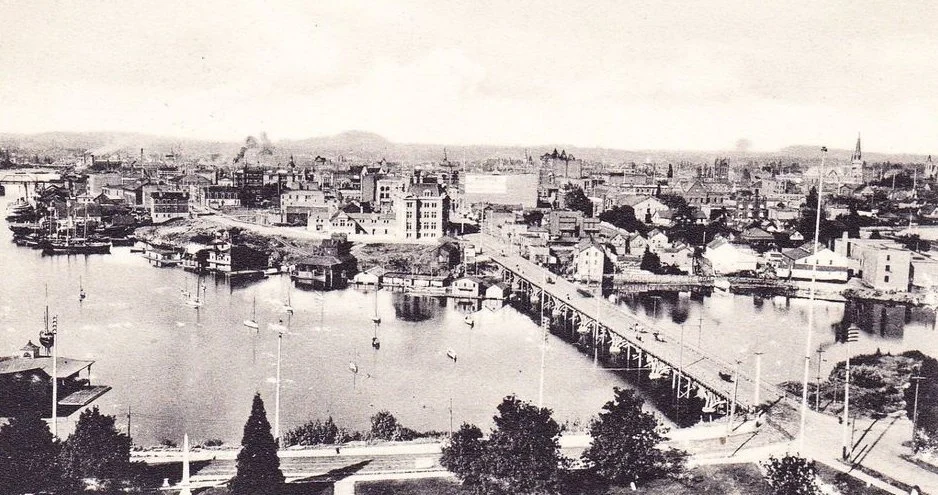

A postcard of Victoria’s James Bay-Inner Harbour, taken shortly after the turn of the last century, or about 20 years after John Hicks was fatally wounded on Oswego Street. Note the bridge (today it’s the Causeway) that linked James Bay with downtown Victoria.) Hicks said that one of the two highwaymen ran off towards the harbour.

Mysterious Affair.

-----

Attempted Murder and Robbery

-----

Mr. John Hicks the Victim Re-

ported to be in a Dying State.

-----

He is Robbed of $1,800 Within a

Few Yards of His Residence.

-----

Shot down, almost at his door!

Such was the grim fate of young John Hicks, the tragic protagonist of a drama that plunged Victoria into mystery, 137 years ago.

For Hicks, the outcome was a painful death; for his bride, grief and angst. For all Victorians, a puzzle which has never been satisfactorily explained.

It is, in fact, one of Victoria’s most fascinating ‘cold’ crime cases of all time. Who dun it?

Ironically, the tragedy opened on a light note, with the gathering of friends at the James Bay home of Capt. Hamilton Moffatt to pay their respects to his niece Mary and her new husband, John Hicks, who were bound for England the next day.

* * * * *

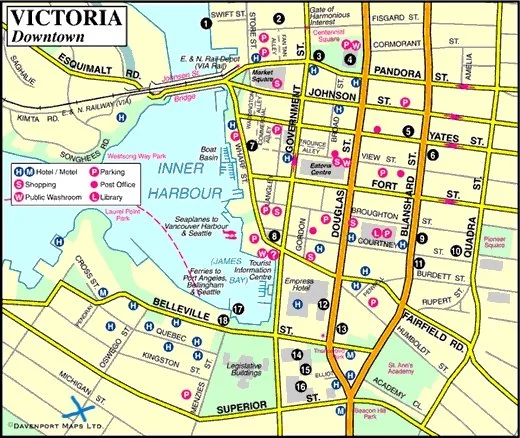

The Capt. Moffatt residence was at the corner of Oswego and Michigan Streets (see X at bottom left), four blocks from the Inner Harbour. —Yahoo.com

Married less than three weeks, they were to catch a coastal steamer for Vancouver the next day before setting off by train across Canada then on to New York by train. Hicks had gone to town by a hack to buy the tickets, intending to return on foot. As the evening advanced, his bride began to glance at the clock, then stepped out onto the front porch to see if he was coming.

Mary Hicks. —Royal B.C. Archives G-0771

Suddenly, all present were startled by the sounds of a pistol shot and scream, Mrs. Hicks having left the door ajar. When she cried out that something was wrong and ran inside, Capt. Moffatt grabbed his own pistol from his bedroom and led the charge to the veranda as two more shots resonated from the darkness.

Racing down the street, Moffatt and company came upon a man lying in the roadway, some 40 feet from the home of James Lascelles, on the northeast corner of Oswego and Michigan streets. To Moffatt’s horror, the fallen man was his son-in-law, who gasped that he’d been shot and robbed by two highwaymen.

Rushed back to the house, Hicks was tenderly placed upon a sofa “in the very room which had but a few moments before resounded to the merry voices of the party,” the Colonist would report the next day. From a neighbour’s telephone, Doctors Milne and Matthews and the police were summoned.

While awaiting their arrival, Hicks gasped out details of his attack.

After returning the horse and buggy, he said, he’d walked straight back to the Moffatt residence on Oswego Street. He was within 50 feet of his destination, picking his way between the puddles in the roadway, when he was assaulted. One of two men seized him by the throat and attempted to “down” him.

As he struggled to free himself, Hicks tried to shout but a second attacker placed a pistol to his temple and fired, the ball passing through his hat and knocking it from his head.

He was then thrown to the ground where they proceeded to relieve him of $1800, a silver watch and a diamond stick pin from his scarf. Because of the force with which they conducted their search, one of the thieves snapped the gold chain of his watch and several links were still clutched in Hicks’s hand when he was found. (Here begins the first of several inconsistencies in newspaper reports and testimony given at the inquest: his watch was gone but the chain was still attached to his vest.—Ed.)

It was as he lay on the ground that the gunman fired again, the bullet passing through his stomach and coming to rest in his back.

This was confirmed by Dr. Milne who, arriving at Capt. Moffatt’s ahead of Dr. Matthews, traced its path. The desperadoes then fled, one leaping over a fence opposite the Lascelles house and running through a field, the other running down the street towards the Inner Harbour. Their flight was witnessed by Mrs. Lascelles who’d been attracted to her window by the shots.

Investigating officers then questioned Hicks, to be told that he hadn’t recognized either man and he didn’t understand how they could have known that he’d withdrawn a large sum of money from the bank that very day. One man, he noted, was tall and wore a moustache. Police surmised that they must have “dogged” him for hours, watching for an opportunity to rob him.

Queried a Times reporter: “A peculiar feature about the affair is that the wretches should have allowed their victim to approach so near the [Moffatt] house before making the attack on him. Had they attacked him one or two hundred yards from the place they did it is doubtful if any person would have heard the report of the [shots].”

According to those present, Mrs. Hicks’s grief was “pitiable to behold,” and it was earnestly hoped that the popular young bookkeeper’s wound wouldn’t prove to be fatal. By midnight, she was reported to be resting comfortably, as Milne and Matthews prepared to remove the pistol ball from Hicks’ back where it had lodged after glancing off a rib and passing through a kidney.

By the following day, numerous theories were being advanced as to the shocking James Bay tragedy. But, already, some were venturing so far as to ask whether Hicks’ wounds were the result of attempted murder–or an attempted suicide.

Hicks, it was reported, had passed a restless night despite his having been administered opiates as an anaesthetic after the surgeons successfully removed the bullet.

* * * * *

Shortly after daylight on the morning after John Hicks was gunned down in a quiet James Bay street by two highwaymen, and as he lay recovering from a bullet which had passed through his stomach and lodged in his back, James Lascelles undertook a personal examination of the field through which one of the assailants had fled.

Lascelles wasn’t a Victoria police detective—his forensic interest was motivated by Hicks’s having been waylaid in front of his house.

Thirty feet from a fence, and about 40 feet from where the wounded man was found, Lascelles spotted a pistol. Of the British Bulldog make, it was quite new and had been fired four times, as evidenced by that number of spent cartridges in its five chambers.

The British Bull Dog was a popular type of solid-frame pocket revolver introduced by Philip Webley & Son of Birmingham, England, in 1872, and subsequently copied by gun makers in continental Europe and the United States. It featured a 2.5-inch (64 mm) barrel and was chambered for.442 Webley or.450 Adams cartridges, with a five-round cylinder. —Wikipedia

Nearby lay an empty buckskin ‘poke’ such as miners of the day favoured for their gold dust, some letters addressed to Hicks and his hat, which smelled strongly of gunpowder. It had been punctured by a ball which had entered the crown at the back and passed out through the front.

When police examined the field from which Lascelles recovered the revolver, they found no unusual marks on the ground or on a fence, although the fence of an adjoining lot showed signs of having recently been scaled.

However, the most intriguing–and confusing–new lead wasn’t in the form of physical evidence, but in the words of neighbour Mary Lascelles who, it was reported, had seen Hicks’s attackers fleeing from the scene.

Here’s where it begins to get somewhat confusing, as the two Victoria newspapers, the Colonist and Times, conflict on some of the key points. What follows is Mrs. Lascelles’s subsequent interview with the Colonist.

To a Colonist reporter: “I went to bed early yesterday evening, being an invalid. My cough was troublesome and I could not sleep, so I raised the blind of the bedroom window that looks out to the road where the robbery occurred.

“About 10 o’clock, I should think it was, a bright flash was reflected on the bedroom wall. Thinking it was a flash of lightning, I listened for the thunder, but instead heard a most unearthly scream, as if from some person in mortal agony. It sounded more like the despairing cry of a crazy man.

“I also heard a report as of a pistol. I said to my husband, ‘There’s a crazy man outside, shooting himself.’ [Still in bed, what made her think that the person firing the pistol was shooting himself? —Ed.) He awoke, then another shot was fired and the screaming was renewed. It was terrible.

“I sprang from the bed and looked out of the window. The light was dim, but I could distinctly see a tall man, wearing an overcoat, walking on the grass at the side of the road. He was coming pretty fast and going towards Capt. Moffatt’s. He was uttering the same unearthly screams that had first taken my attention. He was walking unsteadily, as if he had been hurt.

“When he got opposite my window, there was another flash. I saw it as plain as day. It seemed to come from his own hand. Then he fell forward on his face, got up again and walked in a half-bent position for a short distance. There was another flash and a report, and he fell again.”

Then she saw Capt. Moffatt run to the fallen man’s side.

“While the scene I have described was going on,” Mrs. Lascelles concluded, “there was no one in sight except the wounded man, whom I afterwards learned was Mr. Hicks. If any other person had been there I should have seen him. I am positive the flash came from the hand of the man who afterwards fell in the road.”

So Mrs. Lascelles was quoted by the Colonist. According to a Times reporter, she was lying awake when she heard footsteps outside and assumed it was her son coming home. Then came a flash that reflected off her bedroom wall and the sound of a gunshot. After a second shot she looked out the window, to see a man lying in the roadway and “calling out in a loud manner”.

Upon regaining his feet he walked 20-30 feet, there was another shot and he fell again. “She could see him, but did not see any other person, nor hear anyone running away.” By the time she and her husband had dressed and went outside, the wounded man had been removed to the Moffatt house.

There’s a third version.

Once-eminent B.C. historian B.A. McKelvie wrote of Hicks’s mysterious death in his last book, Magic, Murder & Mystery, which was published by his family six years after his death in 1960. McKelvie, I should point out, was a career journalist who’d have enjoyed the luxury of knowledgeable sources; that said, however, he, too, worked after the fact in the Hicks case, having been born five years later.

McKenzie's version, based upon testimony given at the inquest, differs from that of the Colonist and Times:

Mrs. Lascelles: “We were all in bed. I had a lamp low and the street was lighted a little by the electric light. A little before ten o’clock I saw a flash come on the wall through the window and thought it was lightning. Right after that I heard the report of a pistol and soon after that a man yelling as if he were crazy.

“I then woke my husband. I sat up on the bed, looked through the window and saw a man with an overcoat on standing on the grass just off the road on the opposite side of my window.

“He was still yelling and seemed to be standing still. I then jumped up and remarked to my husband that the man was all alone and I would go out to him, but my husband said, ‘No, he will shoot you.’

“Just then I saw the flash and heard the report of another shot. The flash came from close in front of him, and he fell with his head towards the fence where the pistol was found and [with] his feet towards our house. He appeared to be laying on his back. I could see nobody standing over him and nobody near him.

“My husband then got up. I watched the man, and saw him turn over on his side and get up on his knees and afterwards on his feet, and he walked quickly but stooping as if he was hurt. He walked along the grass at the side of the road towards Mr. Moffatt’s house. After walking a short distance, a third shot was fired which seemed to be in front of his body, like the other, and close after that a fourth shot and then he fell again.”

McKelvie who, as noted, was a professional journalist, questioned Mrs. Lascalles’s testimony by quoting Edward Truman who found Hicks’s empty purse: “I don’t think there was any electric light. I t was quite dark. I had a lantern.”

But to get back to the story:

In the meantime, police had uncovered equally mystifying evidence in town. Hicks said that he’d withdrawn $1800 from his bank to purchase passage for England. But a check of the four banking institutions revealed that he didn’t have an account with any of them although he’d cashed a small English money order at the Bank of British Columbia the day before the shooting.

Further inquiry at the ‘overland’ ticket offices also showed that he hadn’t purchased railway tickets to take them to New York from which they’d sail to England.

Thomas Earle, Hicks’ former employer at an Alert Bay cannery, volunteered the information that, two weeks earlier, he’d paid Hicks $280. Subsequently, Hicks and his bride had honeymooned in Portland, returning several days before the tragedy to make arrangements to go to England. That’s why the newlyweds’ friends had gathered at the Moffatts’ James Bay home for a farewell party.

However, inquiry into Hicks’s movements about town earlier that evening turned up the fact that his hack driver had seen two suspicious-looking men watching his cab, and he’d reported the fact to the police at the time.

Hicks’s friends “scouted” the idea that he could have shot himself. Nevertheless, rumours that he’d attempted suicide due to a “shortness of funds” and his inability to keep up appearances with his bride and her parents, steadily gained ground.

All the while, Hicks, said to be in critical condition, added few fresh details to his original statement that he’d been shot and robbed by two bandits. As for the $1800, he said he’d brought it from England seven months before and had carried it with him ever since.

Despite their having successfully removed a bullet from his stomach, doctors feared the worst, particularly if infection set in.

Even as Hicks fought for his life, rumours continued to spread that he’d staged the robbery to cover a lack of funds and his inability to meet the expectations and obligations of marriage.

On Friday morning, Oct. 30, 1885, 36 hours after he was shot, John Hicks died at the Moffatt home where he’d been treated by Drs. Milne and Matthews.

That afternoon, Coroner Edwin Johnson empanelled a six-man jury and headed for the Moffatt house to begin the inquest. There, after the jury viewed Hicks’s body, Moffatt stated that he’d known Hicks, an Englishman of about 35 years, but a month, the deceased having married his niece Mary and honeymooned in Oregon for the previous two weeks.

The last Moffatt had seen him before the shooting was that same evening when, upon returning home about 8:30, he saw Hicks leaving for town. Neither man had spoken but Hicks, he said, had seemed to be in good spirits.

Just an hour later, Mrs. Hicks, who’d gone to the front door to see if her husband was coming, had rushed into the room “in a condition of great excitement, exclaiming she was sure there was something rough taking place outside”.

When Moffatt heard shouting and two pistol shots in quick succession, he grabbed his revolver from his bedroom and headed for the street. In front of the neighbouring James Lascelles residence, he found a man lying beside the road. When he asked him who he was, the other weakly replied, “It’s me,” and Moffatt realized it was Hicks.

Yelling to Lascelles for assistance, he cradled Hicks’ head on his knees as the wounded man explained that he’d been shot by two robbers. Then a man named Copeland had helped him to carry Hicks to his home. His son-in-law’s overcoat, he said, was splattered with mud and, although very excited, Hicks spoke coherently and appeared to be sober.

Moffatt denied any knowledge of Hicks’s finances, explaining that he’d been surprised to hear of his having been robbed of almost $2,000 simply because he couldn’t understand anyone being “so silly as to pack so much money about with him at all hours of the night.

“I was not surprised to hear that he was possessed of that sum. As far as I know he is a man of remarkably quiet disposition and very temperate, apparently. I never noticed anything strange in his manner or anything to indicate weakness of mind or trouble. Neither do I know whether he possessed any revolver of his own...”

He estimated that it had taken him two minutes to reach Hicks’ side, said that he heard only two shots, and hadn’t heard any “hurrying footsteps”. Yes, he’d observed that both the hat and vest of the deceased were powder-burned.

Other testimony noted the fact that the vest had been penetrated by a bullet, between the third and fourth buttons on the waist, having entered “in a place which would necessitate the muzzle being put inside the vest, supposing the latter to have been buttoned”.

When the inquiry resumed after a break, Capt. Moffatt deposed that he’d recovered the death weapon in a nearby vacant lot, some 70 feet from the centre of the road, after it was pointed out to him by his neighbour, Lascelles. He’d handed it over to police superintendent Bloomfield who’d noted what he said was a bloodstain.

So: who dun it? Readers may have drawn some conclusions of their own from the few facts ascertained by Victoria police and private parties acting as detectives in the fatal shooting of the young clerk, October 28, 1885.

We’ll conclude the fascinating tale of John Hicks next week in the Chronicles.

(To be continued)

* * * * *

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.