‘Lost Mine’ is Like a Moment Frozen in Time

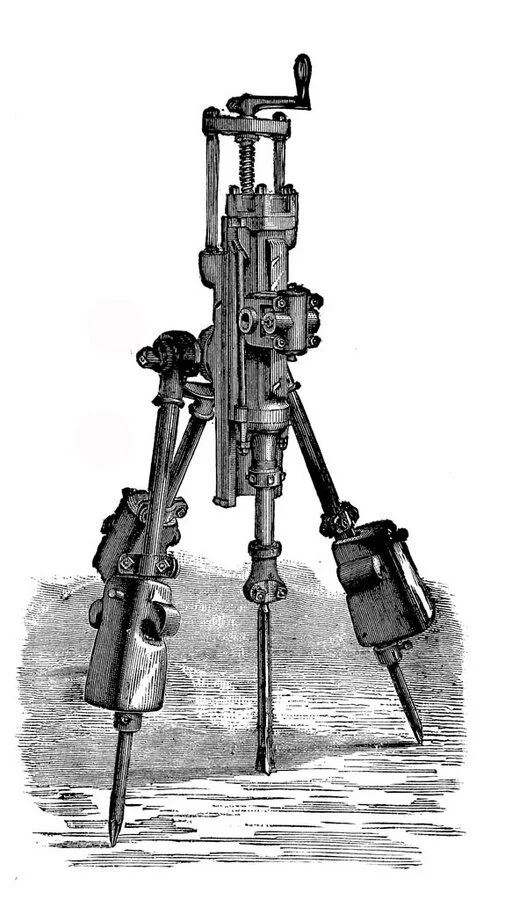

A view of the rock drill that’s at least 120 years old and which should be in a museum. —Henry van Hell photo

You could say that today’s story began at the foot of my driveway.

That’s where, upon returning from my daily walk along the old CNR Tidewater Line by my house, I saw a man standing by my mailbox. As I approached it became apparent that he was waiting for me.

Henry van Hell (“It’s spelled just like it sounds,” he said with a grin), who lives at Cowichan Station and has passed me many times as I walked along Koksilah Road, began with the familiar question, “Are you T.W. Paterson?”

A longtime fan of the Chronicles when they appeared in the Cowichan Valley Citizen, he wanted to tell me about an old mine in the Cowichan Lake area. His brother Walter, a retired professional forester, found it in 1995 and had taken Henry to see it a month before.

Henry was so intrigued that he wanted to tell me about it. To make his point, he showed me several photos on his smartphone.

Instantly, I, too, was hooked.

The equipment on the ground, two boilers, a rock drill and a winch, looked as if they’d been placed there yesterday. Yes, they were rusty, but they appeared to be in great condition, and intact, despite who knows how many years’ exposure to the weather in our Island rain forest.

What Henry wanted to know was, which mine is it and what were the miners after?

He promised to email me copies of his photos and to take me and Jennifer there. In turn, I told him I’d dig into my mining archives and see if I could identify the mine—I, too, wanted to know the who, the when and the why.

Within a week Henry and Walter very graciously fulfilled Henry’s promise to visit the mine and I was able to take several photos of my own. Since then I’ve researched its brief history, the subject of this week’s Chronicle—with one caveat.

In the month since the van Hells’ recent visit, someone else had been there—and left a mess of disturbed soil and uprooted salal and other undergrowth. Yes, I’m an Indiana Jones who digs for bottles and other artifacts at abandoned mining and logging sites. But Jennifer and I don’t leave a mess; we bury rusty garbage and broken glass and replant any bushes we disturb. We’ve also cleaned up after others.

In short, I have no wish to see this historic site further vandalized by my publicizing it.

So, for the purposes of this Chronicle, I’m going to use fictitious names and landmarks where I think it necessary. I can’t stop anyone from utilizing the priceless B.C. Department of Mines records as I’ve done for most of my working career, but at least, if they go to that much trouble, they’ll have earned the right to know.

And the records don’t give the mine’s exact location so, to find it as Walter did accidentally in the course of his work in the ‘90s, they’ll have to bushwhack. I’m hoping that anyone willing to invest that much time and effort will also show respect for the site and its 120-year-old artifacts...

* * * * *

For all my research of mining activity on Vancouver Island, I was mildly surprised to find that the van Hells’ mine wasn’t copper (my first surmise) but iron.

Yes, I knew that Island iron—magnetite—had attracted Japanese interest in the 1960s, but iron at the turn of the last century when gold, silver, copper and coal were the big players throughout B.C.?

Yes, in fact, as early as 1893; and seriously, too, although some very ambitious and serious financial investment doesn’t appear to have resulted in any working mines. In fact, it’s as if these miners left hardly a mark of their passing other than some abandoned exploration holes in the ground, and these mostly overgrown to the point of near-invisibility.

En route to the mine with the abandoned equipment, we stopped at one of these forsaken shafts, this one no more than a test-hole in the side of a hill, and just off the logging road. It’s likely that it was drilled and blasted by hand; the few broken bottles with their open pontils and rusted graniteware pans and coffee pot suggest the 1890s, early 1900s. It’s curious to me that these cooking utensils were left on-site at what would have been a short-lived exploration... Did they leave, intending to come back?

Then it was on to the mine we were really after and an arduous hike through the bush.

Walter, who honed his woodsman skills as a professional forester and recently retired after working in the Cowichan Lake area for 30 years, would have found it without a map. Thanks to the marvels of satellite geo-positioning, however, he showed me our exact position and an outline of the historic mining claims on his smartphone. Unreal—and what a contrast to the days of the first prospectors who hiked these forests with little more than a compass and their hard-won bush sense to guide them!

According to a century-old report of the Department of Mines, the Cowichan Lake district “has received considerable attention owing, no doubt, to the discovery of ore on the four claims now held by the Duncan Mining and Development Company, Limited, viz:-Livingston, Protection, Silvery King and Dot. Work on these claims comprises one open cut 50 feet long; two open cuts 30 feet long; 100 feet of tunnel well timbered, and a cross-cut of 25 feet, all in ore. The tunnel at 100 feet gains 70 feet in depth, and another tunnel has been started 100 feet below No. 1, which has been driven 130 feet, and assays from surface samples give 50 to 68 % lead; $2.50 to $5 gold; 4 % copper, and 6 to 10 oz. Silver... Buildings, comprising bunk, cook and powder houses and blacksmith shop, have been erected.”

Bunk, cook and powder houses, and a blacksmith shop—all built and stocked on spec by investors who never set eyes on the property!

As reported for 1902, the launch pad for much of the exploration between the south shore of Cowichan Lake and the salt chuck was Port Renfrew, “or Port San Juan as it is locally known...an open roadstead on the southwest coast of Vancouver Island...a port of all for steamers plying up and down the West Coast of the Island.

“Two good-sized streams flow into the bay, the San Juan from the east and the Gordon from the north. The country rock on the east side of the harbour is chiefly slate, while on the west side diabase and diorite are most in evidence, the diorites occasionally showing gneissic structure. This same formation is found up the Gordon River and its principal tributaries, but with the addition, on the upper reaches, of a very highly crystallized limestone. A considerable number of mineral locations, covering showings of magnetic iron ore, have been recently made in this section...”

As was so often the case, the startup money came from the Old Country, in this case a syndicate of English capitalists “who’d obtained control of a number of such iron locations”. These had been consolidated into a group on which development work was being pushed, the actual work being chiefly confined to a claim about six miles from salt water. Supplies were hauled in over a well constructed trail (another expense!) and, when possible, by river canoes.

I didn’t need to be Sherlock Holmes to figure out how the camp was laid out.

There had been several cabins on the ledge above the river and, beside the equipment, is the mine entrance which curves to the right where it’s blocked by a third, and larger, boiler. Immediately to the left of the entrance is a shallow off-shoot and the water, which has completely flooded the old workings, is darker, indicating a shaft. In 1995, Walter said, he could see the remains of a ladder and he plumbed it to a depth of 45 feet.

(The perfect argument for not exploring an abandoned mine just because you’re wearing gumboots!)

As a matter of fact, Walter’s plumb bob must have hung up on something at the 45-foot-mark, as the Department of Mines Report states that it goes down no less than 300 feet.

The miners were following a magnetite outcrop which appeared to dip into the hill; at about 100 feet down a crosscut drift of 40 feet had been run to the north which had “cut diagonally through about 16 feet of ore mixed with country rock. Similar drifts had been set off at the 200 and 300-foot levels, simultaneously, that at the 200-feet level being new in about 18 feet, and that at the 300-foot level not so far. “In neither of these drifts, nor in the shaft, was any ore visible, the rock driven through being chiefly diorite, though, of course, these drifts had not been driven far enough to strike the ore outcrop, should it continue at this depth at the surface dip...”

Think of it: All this work was achieved with human brawn and, a true luxury for most miners in those days, a steam-powered drill and winch.

But don’t let these tools, the highest of technology in their day, fool you: this was an amazing feat. The shaft appears to be only about four feet square—the drill, which is at least six feet long, could only have been used at the surface.

Meaning that the 300-foot-shaft and the cross-cuts were bored and blasted by hand. The mind reels...

And all for—what? At the time of the mining inspector’s annual visit, within two-years of the mine’s initial probing at must have been incredible expense, he was informed by the company foreman that the mine and cabins were boarded up, all work suspended, so he didn’t even bother to visit the workings.

Were the investors disappointed?

Certainly—but not enough so to quit. Abandoning their expensive equipment, no doubt intending it to be temporary, they moved several miles to two new claims. These also required the further expense and effort of a wagon road. They were still looking for iron and at an elevation of 800 feet they exposed two outcroppings of magnetite, 120 feet and 20 feet wide, and from 30 to 50 feet high, after stripping the surface of a steep hillside above the river.

At the time of the inspector’s visit, “No work has been done other than the stripping necessary to show up the exposures mentioned. These show on the surface of the bluff very clear[y] solid magnetite, which, from its occurrence, will be easily and quickly prospected by a crosscut tunnel.” But this required that a tunnel be bored to determine “to what thickness the fine surface showing extends, and without which no present estimate of possible tonnage can honestly be made. A sample from the surface gave 63.6% iron and 1.5 % sulphur.”

Do you still wonder why I so admire the entrepreneurial spirit of our pioneer miners?

* * * * *

I’m sure you said to yourself, probably more than once, “They just don’t make things like they used to.”

I’ve already described how the old equipment has withstood more than a century in the rain: the brass controls still move, you can compress the springs with your fingers, and the firebox door of one boiler still swings on its hinges without so much as a squeak.

So it really came as no surprise to me that when I Googled the company name on the drill (Ingersoll) and the maker’s name (Jeanville Ironworks), I found they’re both still in business.

A 1908 postcard of the Jeansville Iron Works, Hazelton, Pa., makers of the drill still in the bush in a Cowichan Lake forest.

An early steam-powered drill; the Ingersoll Rock Drill Co. (now Ingersoll Rand) has been manufacturing them since the 1870s. —https://westernmininghistory.com/library/5570/page1/

Walter van Hell at the entrance to an abandoned mine. Henry can just be seen inside. In this case Walter already knew that the water was just six-seven inches deep—an assumption no one should ever take for granted.

A little WD-40 and this old winch would probably work!

Walter and Henry examine the Ingersoll rock drill which is so big it likely was intended for use in a quarry. It most certainly didn’t work underground in this old iron mine.

You can clearly read, JEANSVILLE IRON WORKS, Jeansville, Pa. The company is still operating.—Henry van Hell photos

* * * * *

For those of you who’d like to know more about the brief but expensive search for iron ore deposits between Cowichan Lake and Port Renfrew, these further reports from the B.C. Department of Mines:

Bugaboo - This location is held by Messrs. Bently and McGregor, of Port Renfrew, Bugaboo. and is reached by a trail from the Baden Powell, two miles in length. The claim is situated on Bugaboo Creek, a small tributary of the Gordon River, at an elevation of 1,400 feet, The creek has cut through a body of magnetic iron ore for about 100 feet. This ore body, as exposed in the bed of the creek from bank to bank, is about 80 feet wide, while some surface stripping on either side has further exposed it. A lime-diorite contact appears to cross the creek here diagonally, the crystalline limestone being on the down creek side, and on this contact the ore appears to have been formed. A small waterfall has been developed in the creek by the solid body of iron ore in the canyon, below which, and on the lower side of the ore body, a drift has been run into the bank, some 40 feet below the top of the ore exposure, which drift is in for 10 feet in solid magnetite. The outcrop is well defined and is remarkably free from admixture with country rock, being nearly pore magnetite, although occasional patches of iron pyrites were visible. This is one of the most promising prospects seen on the Coast, and is well worth serious development, as the ore could be very cheaply mined and transported down the valley, though it would require a railway of about 12 miles to transport it to navigable waters at Port Renfrew. [My italics—TW] There is sufficient water power and timber convenient for all mining purposes... There are some other exposures back from the creek... Samples of the ore gave the following analysis:-69.2 % iron, 2.7 %: silica., 0.5 % sulphur.

PORT SAN JUAN OR RENFREW DISTRICT

This district is known by both names; the former, being the older, is still retained on the maps, while the latter name is used locally and by the postal authorities. The deposits of magnetite in this district occur on the Gordon River and on some of its tributaries, notably on Bugaboo Creek. The Gordon River flows into the head of San Juan bay from the north, and is about twenty miles long, heading in the mountains on the west side of Cowichan Lake.

HISTORY. Prospecting for iron ore on the Gordon river and its tributaries was very actively prosecuted during 1898 and for a few years later, during which time a large number of mineral claims were located, on some of which considerable development-work was done, notably on the Gordon River group, owned by the Gordon River Iron Ore Company; also the Bugaboo group, the property of the same owners: and on the Conqueror group, owned by a Victoria syndicate. This work was being carried on during 1902, when Herbert Carmichael, then Provincial Assayer, made the examinations which are the basis of his report in the Minister of Mines’ Report for that year. Later all work was suspended, and in 1907, when Einar Lindeman was making an examination for the Mines Branch, Canadian Department of Mines, no work was being done on any of the properties, nor has any been done since. Owing to these facts, and because the writer had made an examination for private interests several years ago, it was not considered necessary for him to visit the district during the past summer, especially as none of the owners had representatives on the ground; therefore the following description of the deposits in this district is a compilation from the reports referred to above.

Gordon River - This group of mineral claims contains the following named eleven claims, viz: Rose, Sophia; Rambler, Jen, Puffing Billy, Pig Iron, Cold Steel, Max, Max Frac., Fizz, and Fizz Frac.; and is owned by the Gordon River Iron Ore Company. The total area contained in the group is 362.22 acres. The property is situated on the north bank of the Gordon River about five miles from salt water, and is connected with San Juan Bay by a good trail...

Outcroppings of magnetite occur along the Gordon river on both banks for about a mile, following the contact between the Nitinat marble and plutonic rocks. The work, consisting of trenching at various intervals, shows that the outcroppings are apparently disconnected. Further systematic prospecting is necessary in order to demonstrate the extent of the ore bodies and determine their commercial value....

So much for the iron ore exploration in the Cowichan Lake-Port Renfrew country in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Some interest was again shown in these old prospects in 1916 and in 2015 but, to date, there are no commercial iron mines on Vancouver Island.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.