Lost Silver of Slocan Lake

The box car rolled with each motion of the barge, every gust of wind rocking it more violently on its bed of rails. Then it began to roll—through the guard rails and into the dark depths of the lake, and carrying with it, 24-year-old brakeman, Edward Connolly...

The CPR tug Rosebery and barge breaking the ice on Slocan Lake. —BC Archives photo courtesy of Lost Kootenays and Eric Brighton.

That was in December 1903.

But the boxcar, although long gone and deep in the depths of Slocan Lake, has never been forgotten because of its reputed cargo of 700 bars—a fortune—in silver bullion.

Several attempts at salvage have been made over the years, some partially successful. But the legend lives on, inspiring film makers in recent years to explore the eerie deep of Slocan Lake, not just for looking for those silver bars but for a ‘ghost’ locomotive.

* * * * *

West Kootenay’s 20-mile-long, fjord-like Slocan Lake is a natural wonder in itself but its real fascination lies in its history as part of the ‘Silvery Slocan,’ as this part of the world was known during the decades of a silver boom. It’s deep and dark and sometimes stormy as our story shows.

One might never think it today but, a century and more ago, Slocan Lake was an unlikely but vital link in an inland railway. The Canadian Pacific subsidiary, Nakusp & Slocan Charter, joined the north and sound ends of the lake by rail barge service so as to connect with the Southern Mainline. Even at the height of the silver boom, this marine detour was viewed as time-consuming and costly—but necessary; another cost of doing business, so to speak.

So it was that a boxcar loaded with bars departed by barge from Rosebery in December 1903; so it was that this boxcar found itself, along with poor brakeman Connolly, storm-tossed into the depths of Slocan Lake...

* * * * *

Soundings indicated that the lost boxcar, the property of the Consolidated Mining & Smelting Co., Trail, was resting on a steep slope in less than 100 feet of water. This, however, was subject to drastic change should currents or salvage attempts dislodge it from its precarious perch and send it sliding deeper into the murky depths.

Slocan Lake looks perfectly still in this scenic photo—but when storms lashed its surface in years gone by, it was railroaders beware! —slocanvalley.com

However, company officials remained optimistic when professional ‘hard-hat’ divers assured them that the operation should be relatively straightforward. After several reconnaissance dives, salvagers decided that, rather than risk losing the car, which was canted sharply on its side, by trying to remove its cargo, it would be best to raise both car and bullion intact.

All went according to plan, the divers successfully rigging the car to a barge and, at a signal, crewmen began winching the treasure to the surface. The minutes passed, with only the cables, taut as violin strings, rippling the surface of the lake, the winches protesting shrilly as, slowly, surely, the cables were coiled about their drums aboard the salvage barge.

Finally, a swirling of green water indicated that the boxcar was just inches from the surface.

A hard-hat diver during one of the salvage attempts to recover Slocan Lake’s lost bars. —Courtesy of Arrow Lakes Historical Society

Seconds later, water and mud pouring from its undercarriage, the bullion car rose from the water and the ecstatic salvors cheered its appearance. But their celebration quickly changed to tears when, as they were manoeuvring a second barge underneath the swinging freight car, a cable, stretched to the breaking point, let go with a crack and the boxcar plunged onto the barge’s bow.

As the salvage team watched, stunned, the treasure-laden car appeared to rupture then, in a swirl of white, disappeared into the depths once more. When divers again descended to the Slocan’s muddy bottom, they reported that the boxcar had broken in half and much of its cargo was buried in the silt..

This time, it had come to rest at a greater depth than its original resting place. They’d been beaten.

Thirty years were to pass before treasure hunters again turned their attention—and their hopes—to Slocan Lake’s lost silver bars. Not until the Depression years did another diving firm, also from Vancouver, make a serious attempt at salvage.

For the second time in three decades a diver in ungainly hard hat, air hose and suit, clambered over the side of a barge and vanished beneath the lake’s cold surface. Armed with explicit instructions as to the boxcar's location, Fred Maddison found it easily enough in the gloom, it apparently not having been disturbed since the accident and, after carefully surveying its ghostly remains, he concluded that the silver hadn’t been spilled when the freight car split in two, but remained intact in one-half of the of the car.

His hunch proved correct when, groping through the silt, aware that the slightest careless move could cause the listing wreck to shift and crush him, Maddison felt a jumble of solid objects. Working blindly in the muck and the murk, he cautiously dragged one of the lumps from its fellows and secured it to a hawser.

He proceeded to extricate one bar after another, 57 in total, worth $5000 then, relying upon his sense of touch to locate the unseen treasure. Making his difficult task almost unendurable was the knowledge that at any moment the shattered freight car could roll. Even if he escaped being crushed or buried, he knew that his lifeline couldn’t fail to be entangled or cut by the boxcar’s jagged edges.

If the car should decide to continue its descent along the sloping lake bottom, he knew he was a dead man.

It was this unnerving threat that finally ended his venture. Because most of the bars remained, others, encouraged by this second and successful attempt at salvage, soon tried their hands at outwitting Slocan Lake. But, despite the use of modern and expensive equipment, these latter-day treasure hunters managed to recover only a further 19 ingots, some of which are in a museum and in private collections.

Over the years, the dismembered boxcar continued to move and the lake bottom has shifted. Making matters worse is the fact that surveys in later years indicate that both halves of the ill-fated boxcar are now empty, the heavy bars having shifted in the mud during the underwater upheavals. This theory seems to have been confirmed by reports that a dredge accidentally hauled up several of the long-lost bars when working in the area.

* * * * *

Such is the generally accepted story of Slocan’s lost silver bars. What a shame that I have to inform you that those silver ingots were—lead! Worthy of salvage, sure, but, alas, it is what it is!

Curiously, this isn’t the only tale of lost ‘silver bullion’ in an interior B.C. lake, a second one paralleling our story almost to a ‘T.’ In 1970, a Victoria newspaper reported, "When the murk of the spring run-off settles on Kootenay Lake this spring, a Sidney-area skin diver hopes to slip quietly into the water and locate a missing train load of silver.

"Peter (Trumpet) Thornton Trump, with three diving companions, will resume the search he gave up 13 years ago for several boxcars of ore that broke loose from a CPR train in 1921 and rolled into the lake...."

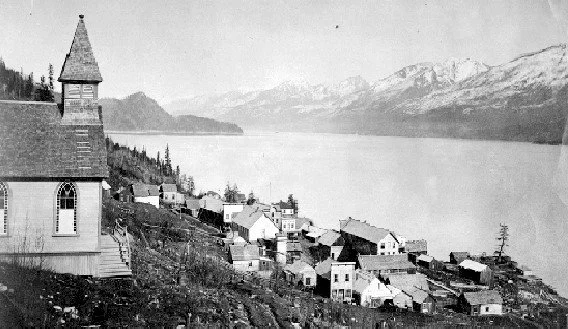

An early view of Ainsworth, Kootenay Lake, which has since been raised by damming. —British Columbia Archives

The Chilliwack-born graphic artist and diver said that the railway had lost many such freight cars over the years, their contents presenting a tempting target to salvors. Ten years earlier, he explained, a Victoria diver named Bill Hook had almost hit the jackpot in Kootenay Lake’s cold depths. “While we were diving for our wreck, Hook was diving for another one further up the lake.

He found the boxcars after two years’ search but apparently thought they were empty. Some other divers were watching him and after he left they brought in a tug and turned the box cars over and found two bars of silver."

His own initial attempt had been thwarted by shortness of adequate air equipment, he said.

At last report, Thornton-Trump and partners were again headed for Kootenay Lake to pinpoint the location of the treasure cars they had in mind. But Kootenay Lake, like its western neighbour, Slocan Lake, guards its treasures well, be they silver or be they lead—or even a ‘ghost’ train.

* * * * *

As recently as November 2023, an online headline blared, The 70-year-old mystery of a vanished BC train has been solved. Vanished, as in “the dark depths of one of BC’s deepest lakes”—Slocan, of course.

This drama dates back to New Year’s Eve, 1946 when a tugboat began towing a barge of railway stock. A barge that was leaking, as it turned out, and when it became apparent that the towline could pull them down with it, the crew members of the tug quickly cut the hawser and watched it and its cargo disappear.

As it turns out, there’s a mystique to lost locomotives. There’s even a website devoted to Sunken Locomotives in Canada which lists three in B.C. (it’s incomplete according to anecdotal evidence in my files), including CPR locomotive No. 3512, the subject of this tale.

Like its legendary silver bullion, Slocan’s lost locomotive has fascinated people for years, most recently a documentary film company whose producer Colten Wilke compared skin diving the Slocan’s bottom while looking for a train engine to be like “searching in an Olympic-sized swimming pool for a grain of rice”.

Giving the 90-minute documentary The Last Stop: Canada’s Lost Locomotive a topical touch was an interview with the last surviving crew member of the tug boat, 99-year-old Bill Chapman who was asleep in the caboose. Alerted by the tug’s captain to abandon ship when the barge began to sink, he and fellow railwaymen piled aboard the towboat with just minutes to spare and there were no casualties.

But, lost, 91 metres (300 feet) down—although not forgotten—were Engine No. 3512, its tender and its caboose.

For railway enthusiasts in the Chronicles audience, this unedited snapshot history of Slocan Lake’s lost locomotive from Locomotive Wiki:

Canadian Pacific No. 3512

Canadian Pacific No. 3512 is a Class "N2" 2-8-0 "Consolidation" type steam locomotive built by the Montreal Locomotive Works for the Canadian Pacific Railway.

History

Canadian Pacific No. 3512 was constructed by the Montreal Locomotive Works as one of the Canadian Pacific Class N2 locomotives, and it was delivered to the Canadian Pacific Railway after it was constructed.

On January 1, 1947, No. 3512 was on a rail barge over at Slocan Lake in British Columbia, on that day, the rail barge that contained No. 3512, several cars owned by Canadian Pacific and a Rotary Snowplow had began to list heavily, then had tilted heavily and then sank causing the engine, the cars and the one Rotary Snowplow to go down with it into the lake, no one was killed in this accident.

As of today, No. 3512 is still lying 600 feet (182.88 feet) deep on the bottom of the Slocan Lake still remaining fully intact, however, is in-fact considered as a preserved example of the Canadian Pacific's Class N2, three other preserved examples of the Canadian Pacific's Class N2 are still around, those being No. 3651 on static display at Lethbridge, Alberta, No. 3716 in running condition for excursion trains, and No. 3522 on static display at Bienfait, Saskatchewan.

A better image of a locomotive of the type that rests on the bottom of Slocan Lake. —Wikipedia