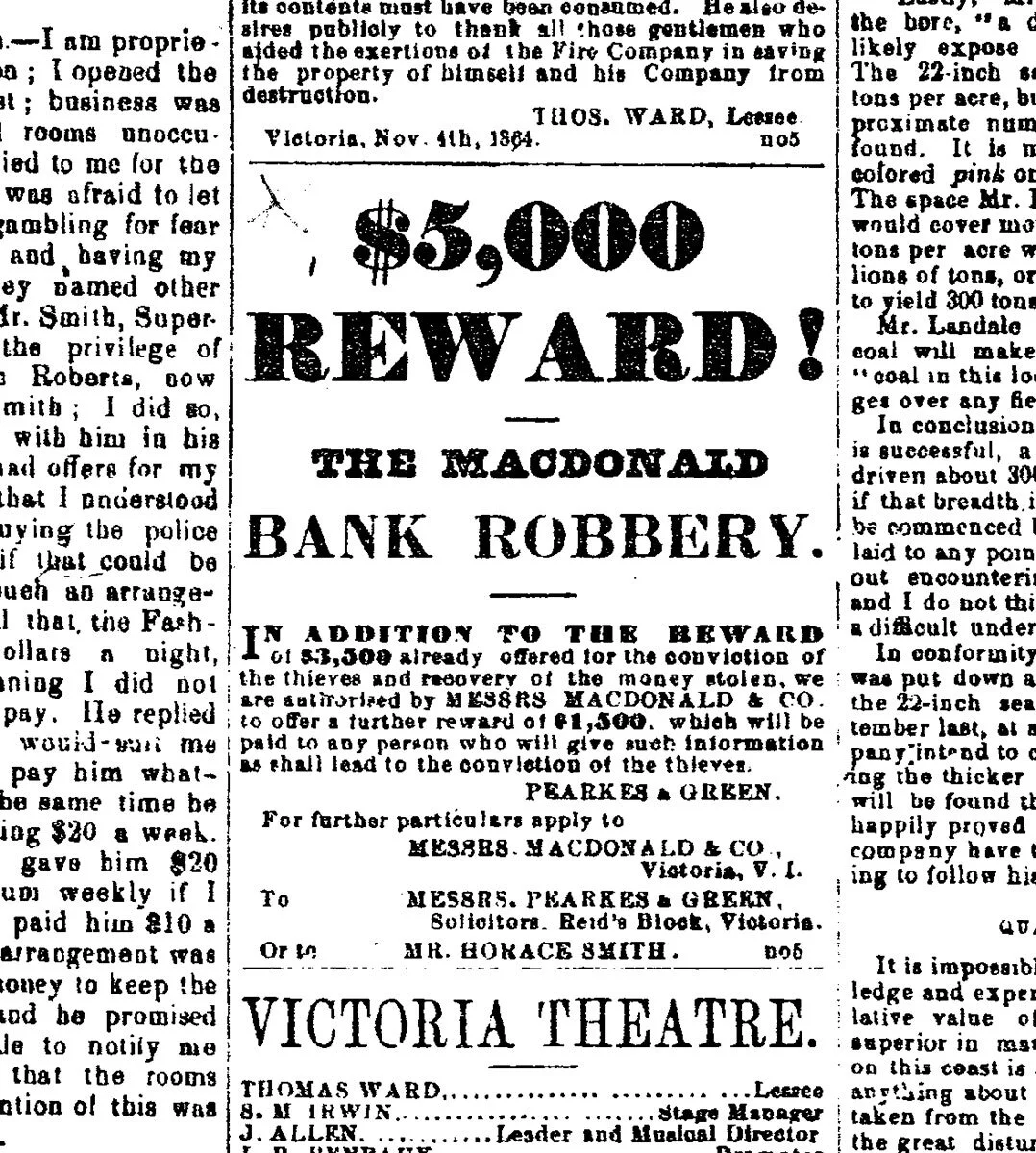

Macdonald’s Bank Robbery (Part 2)

The reward poster seeking information and conviction of those responsible for robbing Macdonald's Bank. Like the poor police investigation it achieved nothing.

So: who did rob Macdonald’s Bank in the early hours of September 23, 1864?

How did the thief or thieves know of the $30,000 in gold, silver and banknotes (the equivalent of $900,000 in today’s dollars) that was being kept overnight before shipment to the Cariboo in the morning?

The brazen theft had to have been planned, as evidenced by entry to the bank having been made by means of a ladder of the exact length required to descend from a skylight, and a key found on the floor that fit the safe lock.

The only “suspect” taken into custody was clerk and bookkeeper Josiah Barnett who was later released for lack of evidence without, according to the Colonist, a blemish on his character. (His arrest would appear to substantiate accusations of a lacklustre police investigation.) We can probably dismiss bank courier R.T. Smith who lost his savings, some $13,000, in the theft and who went on to a colourful career in the western United States, as I shall tell you next week.

Banker A.D. Macdonald? He was in the Cariboo when the bank was robbed and by all accounts had to work for a modest living thereafter.

So, if we discount unknown third parties, it was, as many suspected at the time, an inside job. This brings us to manager John Waddell. Little seems to have been known of him prior to his taking on the job of bank manager but subsequent information suggests he had a nautical background.

(He it was who rowed a fleeing MacDonald all the way out to Race Rocks to flag down a steamship.)

This is where the wonders of the internet come into play. When I first researched the Macdonald’s bank robbery I was all but limited to local sources such as the Colonist and other sources in the Provincial Archives. But that’s not the case today thanks to Google. A few strokes of the keyboard to insert John Waddell and, voila! we find a wealth of information courtesy of William R. McNeill in his fascinating Maritime History of the Great Lakes .

More recently, in March of this year, the Chatham Daily News ran a two-part series on Capt. John Waddell by historians Jack and Lisa Gilbert. The first instalment, “The strange case of the wreck of the Explorer,” tells how the schooner’s owner and operator, Capt. Waddell, was a well-known resident of Chatham, Ont. who’d been sheriff of Kent County for several years. Waddell used the year-old schooner to carry equipment and freight to several lumber mills he owned in the area.

Until November 1867 when Waddell, two crewmen and the Explorer “cleared the St. Clair River and disappeared into Lake Huron with merchandise, mill machinery and barrelled liquor for the Bruce Mines...”

All of this—building a schooner and buying several sawmills—within three years of the Victoria bank robbery!

In December 1867 a sensational account of the loss of the Explorer was reported in the Owen Sound Comet. A week before the Erie Daily Dispatch had reported, in a single sentence, that the “yacht” Explorer had wrecked at Cove Island, Georgian Bay, with the loss of two lives. According to the much fuller account in the Comet the Explorer had capsized on Middle Rock, near Yeo Island, Lake Huron, and two seamen, William Starnes and a man known only as Jack, were missing, “the Master, Waddel [sic], alone reaching the shore...”

The vessel had been bound for a sawmill on Georgian Bay with supplies and merchandise for a trading venture after sailing from St. Clair Rapids. For three days the two-masted schooner battled a fierce gale and its fore-boom was carried away. While heading for Owen Sound Channel it began to snow and visibility was reduced, making navigation all the more difficult. In a patch of shoal water “the sea broke so heavily she was thrown on her beam ends, and the cargo shifted to port, causing her to drag along, with her lee rail under water in a dangerous position”.

To enter the hold to trim the cargo the crewmen had to chop their way through a bulkhead; when one entered with a lantern to survey the damage he reported that the cargo could be trimmed if the vessel could be kept steady for 15 minutes. A second seaman entered the hold to assist, leaving a third man “to signal on the deck in case of danger,” with Capt. Waddell at the wheel.

No sooner had they entered the hold than those on deck heard the sound of heavy breakers and a heavier sea lifted the vessel by its stern until it was almost perpendicular before breaking midships and “filling all the decks up with water, rushing the vessel forward and driving her against the rocks, which she struck with such force with her forefoot or bowsprit, that her whole cargo fell forward with a crash into her bow.”

Starnes and Jack in the hold were crushed and thought to have died instantly.

With his remaining sails in shreds, his ship rocking violently in the waves, Waddell abandoned the wheel and sprang for the rigging just as an eight-foot wave capsized her, tearing away cabin doors and wheeling her about until she again faced seaward. By this time her bow had dropped to an angle of about 60 degrees, only her stern showing five or six feet out of the water. The yawl lifeboat had been jammed, upside down, in its davits and as the Explorer began to drift sternward, Waddell continued to cling to the rigging for his life. (No further mention is made of the third seaman in this report.)

Not until noon the next day, some 18 hours later, did he succeed in clearing the boat from its davits and bailing it out. By then the wind had shifted to the northwest and Waddell was able to make it to shore “in a famished condition” having subsisted on only a few fish.

He was in such a sad state that, when he finally pulled into a dock, he had to be helped ashore. A search party was then dispatched to see if any trace could be found of the Explorer.

Such was the tale of shipwreck involving this mariner identified only as Capt. Waddell as told by the Comet in December 1867. It was 15 years before his name again made the news, again in connection with the ill-fated Explorer. Under the headline, A MYSTERY CLEARED UP, the Meaford Monitor reopened the story of the sinking of the Explorer by telling how she was lost while on her way to Tobermorey Bay with a cargo of whisky, pork and mill casings. Only Capt. Waddell escaped; he said she’d gone down on a reef near Bear and Flower Pot Islands, taking his two (not three) crewmen with her.

Fortunately, he’d been insured. A year later, he was drowned while en route to Flower pot Island in a small boat. Some believed that he was returning to the island to recover the ‘lost’ cargo which he had, in fact, hidden ashore. “Suspicions of foul play were rife at the time, but the vessel could not be found, and the interest in the matter died away...”

Ten years passed before Charles Earle discovered the wreck in 17 fathoms (100 feet down) “several miles from the reef alluded to” by Capt. Waddell. In the spring of 1882 the Port Huron Wrecking Co. raised her and towed her into Tobermorey Bay.

While she was yet on the bottom, on her beam ends, a diver had examined her but couldn’t enter her until she was righted in the course of preparing her for salvage. The act of moving the hulk sprung open the cabin door and, to his horror, he saw the corpse of a man “upright in the cabin”. But when the schooner was towed to shallower water the body couldn’t be found and it was supposed that the motion of towing had caused it to be washed from the wreck.

Then came the grand finale, the culmination of years of suspicion that Capt. Waddell had scuttled the Explorer for the insurance money!

“There are,” said the Monitor, “thirteen two-inch auger holes in her bottom, and from eight to ten tons of stones, but not a particle of cargo”.

Not so fast, responded the Goderich Star, which published the “other side of the sensational narrative” of the loss of the Explorer. “Ever since the raising of the wreck of the lost [Explorer], a story has been going the rounds of the press, in some cases receiving fresh additions from the recording scribes, reflecting most severely on the memory of the late Captain Waddell, and causing his family no little personal anguish. From competent authority we gather the following as the true story of the vessel and its wreck...”

Waddell had built the Explorer, said the Star, in 1866 as a yacht. (This is just two years after the Macdonald’s Bank debacle, remember.) She cost $5000 and could carry up to 2500 bushels of grain in her hold, meaning that, yacht or no, she could be used to transport a modest amount of freight. In the fall of 1867 he loaded a cargo of “goods” for delivery to the large sawmill he owned at Waddell’s Mills on Georgian Bay. Although the Star didn’t specify the actual contents of the cargo it denied the rumours that Waddell had taken on a cargo of whisky and goods valued at $18,000. The true value of the cargo, according to the newspaper, was $2000 which was “vouched for by respectable firms, some of whom are now in existence and were insured for the sum of $1500 and the hull for $2000”.

Fast-forwarding to the time of the salvaging of the wreck, the Star stated there was nothing in its condition or position to contradict Waddell’s account of her sinking. He’d claimed that when the Explorer crashed onto the shoals he’d called to the seamen below, received no answer, so cast off in the yawl boat and drifted for five or six days. He said it had taken him two weeks to recover from his ordeal.

But what of the stories of scuttling? Not so, said the Star which claimed to have examined the bottom of the salvaged Explorer and found no auger holes. Or a skeleton. It didn’t mention a cargo of stones.

As for Capt. Waddell having made a substantial insurance claim? “There being no cargo of any great value in her at the time, insurance on it was not claimed, and no more than ordinary precautions were taken before the hull insurance was paid.”

Why, asked the newspaper, would Waddell have deliberately wrecked his own vessel which had cost him $5000 to build for an insurance rebate of half that amount?

This account ends by noting that all of Waddell’s sons were living and were successful businessmen.

By this time the salvaging of the Explorer and the stories swirling about her of barratry and bodies had become a regional sensation. Next to take the spotlight, in the Port Huron Times, was “submarine diver” R.G. McCullough of that city, who’d worked underwater to secure lines to the hull and who wanted to refute the account which had appeared in the Star.

McCullouch: “Sir,—I see by your valuable paper that the Goderich Star denies the fact that the schooner Explorer was scuttled and sunk, as published in the local papers. I was one of the divers that worked on the Explorer and gave the report to the press concerning the scuttling of that craft, and from personal knowledge know that the Explorer was scuttled.”

He suggested that the editor of the Star board the raised craft with the Goderich harbour master who’d be pleased to lift up her limber boards and show him 12 inch-and-a-half holes, eight on the starboard side and four on the port side.” McCulloough had even found seven of the plugs which had been cast aside after being removed to allow the vessel to fill.

He wasn’t finished. The schooner, he said, had been stripped “of all her sails, blocks, rigging, and booms, and the sheet blocks were cut with a cold chisel...and the lamp and compass were taken out of the binnacle box”. By his estimation the schooner had been loaded down with up to 15 tons of stones; even the lockers had been filled with rocks.

Which brought him to the reputed accounts of bodies having been found in the wreck. “There was one perfect body found on board with a shirt and pair of plants on, and the bones and putrid flesh of another was found on deck, having evidently floated out by the surging of the water while we were working at the wreck.”

He noted that the hatches had not only been securely fastened

but were spiked down.

In short, diver McCullough had “no hesitation in saying that the schooner was scuttled and then sunk”. He concluded his sensational account by saying he didn’t know who’d scuttled the Explorer but the facts he’d presented as evidence of her having been deliberately sunk “can be proved by a dozen witnesses”.

He also alluded to a Mr. Lewis, not Capt. Waddell, as being the real owner of the Explorer, suggesting the possibility that Waddell had chartered the schooner.

According to the Meaford Monitor, its counterpart, the Port Huron Tribune which had carried diver McCullough’s charges that the schooner had been scuttled, responded by giving the name of D.S. Gooding, a Chicago attorney likely acting for the Waddell family, who’d stated that he had a clear case of libel against the Tribune. The newspaper was nonplussed: “He is cordially invited to wade in and try it. We have the best authority for every statement made in that article and are prepared to back it up any time.

“We do not state it is a fact Waddell scuttled the Explorer, but give the story told by himself and the conditions in which the vessel was found. People can draw their own inferences!”

The Tribune based its confident stand on the basis of three professional mariners beside diver McCullough who’d participated in the Explorer’s recovery from the bottom of Lake Huron. Capt. Waddell, of course, having been drowned some years previously in a boating accident, couldn’t speak for himself. The salvors, it was noted in a final parting shot, had had to fill the auger holes and jettison the cargo of rocks to re-float the Explorer!

The ill-fated schooner’s roubles weren’t over. Repaired and returned to service she struck a wharf and sank in shallow water. Less than three months later, having again been repaired, she and crew went down near Stokes Bay, Bruce Peninsula, this time for good.

When news stories of a “Capt. Waddell” being involved in the suspicious loss of his schooner made it to the West Coast the connection was made between the Ontario mariner and the Victoria bank manager of old. In 1870, the Colonist had reported his death by drowning in Lake Huron while sailing with his 17-year-old son. Their boat had capsized, pitching father and son into the lake. The youth had clambered aboard the overturned boat but Waddell Sr. had drifted away to his death. His body was later recovered and he’s buried in the Goderich cemetery.

In 1882, the west coast marvelled at a news story which had originally appeared in the Toronto Globe. The article told how, in 1867, a trading schooner had been lost with most of her crew. The sole survivor, a Capt. Waddell, said she’d wrecked on Shingle Shoals and gone down with a valuable cargo of whisky and mill machinery. Despite the “fishy” nature of the master’s story, the insurance was paid. Capt. Waddell subsequently obtained command of another vessel as navigator but “his luck...seemed to have abandoned him and he met with continued mishaps”. Three years later, he was drowned.

When divers finally penetrated the wreck of the Explorer and confirmed she’d been scuttled, the authorities could only surmise that Waddell had murdered his crew and sunk the schooner for the insurance.

Upon reading this report former banker A.D. Macdonald told reporters of the time John Waddell had managed his bank in Victoria and said he was “almost certain that Capt. Waddell was the guilty party”.

By then, of course, Waddell was long dead, having been drowned in 1870. He again made the news when it was reported that the son who’d been boating with him on that fateful day had been arrested at Owen Sound on the charge of having murdered his father by throwing him overboard in Owen Sound “to possess himself of several thousand dollars which the father had acquired through an act of piracy in sinking a schooner to get the insurance money”.

(If ever you doubted that truth is stranger than fiction—!)

Did John Waddell steal the $30,000 while managing Macdonald’s Bank? His having the money to build a yacht and to buy sawmills in Ontario within three years of the robbery certainly points a finger at him as being the culprit. Way back in 1969 when I first told this story, at the time of the Macdonald mansion’s being razed to make way for an apartment building, I ended my article in the Colonist on this note:

“Today, who can know for sure? Perhaps the ancient bricks of Springfield House, recently sold for use in modern homes, know the real story.

“If only they could speak!”

(To be Continued)

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.