Make That ‘Backacher’ Street

A stroll along Ladysmith’s Sixth Avenue is a stroll into the past—Boer War era.

Fourteen streets, 10 of them running east-west in 11 blocks commemorate senior British officers of the 1899-1902 conflict also known as the South African War. The name of Ladysmith itself, of course, is founder and coal baron James Dunsmuir’s tribute to the two and a-half year-long struggle between the British and the Dutch colonials known as Boers.

Of Ladysmith’s militarily-inspired streets, Baden-Powell is the most recognizable today—not so much for its namesake’s Boer War service as for his claim to fame as ‘father’ of the Boy Scouts and inspiror of the Girl Guides.

Not too many of us will identify the achievements, military and otherwise, of Messrs. Symons, Warren, French, Buller, Gatacre, Robert, White or Methuen although Kitchener might ring a bell. (There’s a city in Ontario named after him.)

All were in the thick of the South African campaign (Canada’s first foreign war, incidentally), thus in the news of the day, and that’s why they’re on Ladysmith signposts more than a century later thanks to Dunsmuir’s building his seaport for Extension coal.

Coincidentally as I write this, many of our heroes of our colonial past have been drawing critical appraisals of their performance as never before, and some of those ‘heroes’ have been found, with the benefit of hindsight, to have had feet of clay. Increasingly, statues and other monuments have been defaced or toppled, names erased from public institutions and streets.

So let’s look at Ladysmith’s streetside Hall of Fame—objectively, yes, but let the record speak for itself!

* * * * *

British troops hauling a gun up the railway line: Battle of Stormberg 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War. —britishbattles.com/great-boer-war

First up is Maj.-Gen. Sir William Gatacre (1843-1906) who, if nothing else, qualified as being one of the Boer campaign’s more colourful principles. In India he’d earned promotion for his “zeal and bravery,” and he later participated in the relief of Khartoum. His men who, like it or not, had to share his passion for physical fitness, called him “General Backacher.”

In South Africa Gatacre found that it took more than physical stamina to defeat a determined foe. He proved this by losing the ‘battle” of Stormberg which one critical historian has dismissed as an “ill-managed skirmish”.

Gatacre, it seems, was bull-headed. His disdain for the military skills of colonials set him up for what for what we now recognize (post-Vietnam) to be the challenge of a regular army, despite its superior numbers and firepower, to defeat a guerilla force on its own soil.

Personally “brave as a lion” and indefatigable, Gatacre also insisted upon total obedience. He refused to accept advice—indeed, in the words of Field Marshal Lord Roberts, he failed to exercise the most elementary strategic sense. Something like a bull in a china shop, he determined to take rail town Stormberg in a surprise attack on Kissieberg Ridge.

To be fair, he did choose the cover of night, while foregoing such superfluities as reconnaissance. This, with the result that most of his army lost its way in the dark. Those who did make it to the correct staging area, to find no one there, headed back to base!

This is making light of a difficult situation. They had no maps, no guides and they were near exhaustion, having had to drill all day in the African sun. (Gatacre believed in fitness, remember, not R&R.) They were two hours late in beginning the march to Stormberg and, by the time they found their way, dawn was breaking.

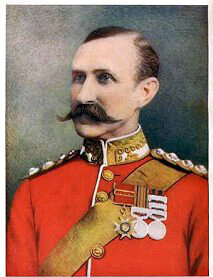

General Sir William Gatacre believed in physical fitness over almost everything else—including sensible military tactics. —britishbattles.com/great-boer-war

Gatacre’s plan was to storm the heights at bayonet-point but his men found themselves at the foot of of Kissieberg Ridge in full view of the enemy. At their head, as they marched in form, was Gatacre (no one questioned his courage). They were literally between a rock and a hard place when the Boers opened fire.

Amazingly, the Irish Rifles managed to scale the heights, only to find themselves the target of their own artillery. In the ensuing barrage their commanding officer was killed.

The Fusiliers—those who weren’t too tired to attempt the ascent—picked their way up a steep rock face under heavy fire, faltered at the halfway point, then fell back. Gatacre, seeing their withdrawal, ordered a full retreat under cover of artillery fire and his cavalry.

The Boers had lost nary a man, Gatacre left 25 dead on the field, 600 prisoners and suffered more than 100 wounded. When the Boers mopped up, they found some British officers just as they’d fallen—asleep!

Hauled on the carpet, Gatacre confirmed the worst suspicions of his competency by producing a map of the ‘battlefield’. It was four miles off-target.

Four months later, Gatacre struck again. A British outpost was overrun and more than 500 men taken prisoner because he wouldn’t go to their relief. This time Lord Roberts canned him. Did it hurt his career? The Official History of the War attributed his defeats to “exceptional misfortune” and he was promptly promoted.

In fairness, he has been described by a fellow senior officer as “one of the hardest-working men I ever struck, whether at his desk at DQMG in India, or on horseback, or on his own legs”. This officer also blamed Gatacre’s failures as being “very largely the case of that fickle jade, called the Fortunes of War... I think it will be admitted by those who have studied the matter, that General Gatacre’s luck was dead out...”

Gatacre, by this time knighted, retired in 1904. Two years later, during an exploration of Abyssinia, he died of ‘fever.’

* * * * *

As an American general once said of leading an army in war, to be great is fine, but to be lucky is better and Gatacre’s misfortunes in South Africa pale alongside those of General Sir Redvers Buller. Said to have been loved by his men because of his concern for their welfare and his willingness to share their dangers and discomforts, “Buller” has been in the news lately because of a call by Exeter City Council to review the appropriateness of his statue at the entrance to Exeter College. (But this is getting ahead of our story...)

It won’t be the first fall from grace of a once highly acclaimed officer who went from being a Queen’s favourite to a King’s pariah. According to The British Empire, Redvers Bullen has “become a byword for military stupidity and out-dated attitudes to changing 19th century society”. He was even ridiculed for his appearance, his double-chin, what has been described as his “cow-like expression” and his name Buller all suggesting “a bovine character”.

Some have ridiculed General Sir Redvers Buller for his appearance and his war record in South Africa--but for not his courage. —warhistoryonline.com

But there was nothing cow-like about his military career—he was ”keen and tough with good military skills,” according to General Sir Garnet Wolseley, his senior officer during the Red River expedition in Canada in 1870.

As a lieutenant-colonel in command of the Frontier Light Horse during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 he distinguished himself when leading a force of colonials (some of them Boer settlers he’d later face as foes) and won the Victoria Cross. His citation says of the future C-in-C: “Lieut-Col Buller, while being hotly pursued by Zulus, rescued a captain of the Frontier Light Horse (Capt D'Arcy) and carried him on his own horse until he overtook the rearguard. On the same day, under the same circumstances, he carried a lieutenant (C. Everitt, also of the Frontier Light Horse), whose horse had been killed under him, to a place of safety. Again on the same day, he saved a trooper (also Frontier Light Horse) whose horse was exhausted, and who otherwise would have been killed by the Zulus who were within 80 yards of him.”

Highly praised, he was appointed ADC to the Queen “with whom he got on famously,” and was so dedicated to the army that he interrupted his honeymoon to serve in Egypt. But then he made his first mistake by quarrelling with his some of his fellow officers, including his old mentor Wolesley, and making an enemy of the HRH Prince of Wales. This would “rebound on him badly when the [Prince] became King,” according to the BE.

For 10 years, almost by default, he virtually commanded the British Army from behind a desk, first as Quarter-Master General then as Adjutant-General, winning the affection of servicemen at the expense of alienating politicians (including Lord Lansdowne, the Secretary of War), bureaucrats and the civil service.

Buller apparently was among the most surprised by his appointment as C-in-C of the South African Expeditionary Force, at that time the largest ever mounted abroad by Britain.

Back to the British Empire: “At first the campaign seemed to go well and when Ladysmith was besieged he decided to take most of the army to Natal. But his attempts to relieve Ladysmith failed badly at Colenso, Spion Kop and Vaal Krantz. It was especially unfortunate that Lord Roberts's son was killed at Colenso; Buller received much of the blame for this and Roberts, his successor, could never forgive him.

The main criticisms of Buller's command in South Africa were:

—His failure to inform Milner of his departure to Natal

—His refusal of the offer of Colonial Cavalry

—His abandonment of the guns at Colenso

—His stock of champagne

—His failure to pursue the Boers after the relief of Ladysmith

His biggest mistake was in sending a telegraph to Lansdowne in which he implied he was about to abandon the attempt to relieve Ladysmith and his advising General Sir George White, in command of the Ladysmith garrison, to surrender. Only after Lansdowne demoted him and put Lord Roberts in command did Buller pull a hat-trick by capturing Pieters, formally entering Ladysmith, occupying Machadodorp, defeating Boer General Botha at Lydenburg and marching north as far as Pilgrim's Rest and occupying the principal Boer positions.

He returned, apparently with willingness, to his former command of Aldershot only to be sacked within a year for breaching Army discipline by publicly answering a scurrilous newspaper article in a public speech. His appeal to the king whom he’d offended when he was the Prince of Wales was ignored and, declining an offer to run for office, he retired to his estate where he died seven years later.

But if Redvers Buller was reviled officially, his former soldiers revered him with good reason: “Under him the army never lacked for anything, nor did they suffer the same hardships or disease which [characterized] Roberts’s operations”.

* * * * *

Which brings us to Redvers Buller’s successor, Field Marshal Frederick Roberts (1832-1914), first Earl Roberts. Even to paraphrase this remarkable officer’s military career would take several pages. Long before he went to South Africa he’d established a military record almost without equal, including winning the Victoria Cross. Among the most successful and most decorated British officers of his day, he’d previously served in India, Natal, Abyssinia and Ireland and became the last Commander-in-Chief of the Forces before that post was abolished. His phenomenally successful military career coincided with the peak of Great Britain’s world power but he was too old and within two years of his death, by the time of the First World War.

Field Marshal Frederick Roberts won battles and honours but lost many of his men to disease because of supply line inefficiencies. He’s also remembered for having interned 1000s of Boer women and children in a concentration camp where many, most of them children, died of disease and hunger. —Wikipedia photo

Of slight build, his physical appearance belied his courage and strength of character. As with General Gatacre, his men also gave him a nickname—this one affectionate—“Bobs.”

Besides his golden service record Roberts had the benefit of massive reinforcements when he took over from the disgraced Bullen with whom his son was serving and would earn a posthumous VC. Personally leading a two-pronged offensive across the open veldt into the Orange Free State, Roberts raised the siege of Kimberley at the Battle of Paardeberg in February 1900, forced the surrender of 4000 Boers under General Cronje, scored another victory at Poplar Grove and captured Bloemfonteirn, the Free State capital.

Then he, too, hit a pot hole. His decision to reorganize his army’s “logistic system on the Indian Army model in the midst of war” led to a shortage of supplies and a typhoid epidemic that “inflicted far heavier losses on the British forces than they suffered in combat”.

By spring, however, he was again on the march, capturing Pretoria, the capital of the Transvaal at the end of May, defeating another Boer force at Diamond Hill and linking up with Buller at Bergendal late in August. It was the last of his many victories and with the war all but ended he handed over command to Lord Kitchener to return to England and more honours: Earl Roberts of Kandahar and Pretoria, Viscount St. Pierre and Knight of the Order of the Garter.

But Lord Roberts, hero supreme, is being remembered now for a negative legacy: his introduction of what we now term concentration camps.

To discourage Boer rebels he had their farms burned and their families interned behind barbed wire where the lack of space, food, sanitation, medicine and medical care resulted in rampant disease and a high death toll: 26,370 women and children inmates—81 per cent of them children. Roberts also utilized, if not introduced, the practice of using hostages to deter guerilla attacks on trains.

Among other post-Boer War accomplishments he introduced the Short Magazine Lee-Enfield rifle, improved education and training for soldiers, promoted inscription and, in 1912, to mostly deaf ears, warned that war with Germany was inevitable. He and Sir Winston Churchill are the only two people who are not members of the royal family to lie in state in Westminster Abbey. Buried in St. Paul’s Cathedral, he and his son, The Hon. Frederick Hugh Sherston Roberts, are one of only three pairs of fathers and sons to be awarded the VC.

* * * * *

Major-General Sir William Penn Symons, 24th Foot, was a veteran of the Anglo-Zulu War and two Asian campaigns before being re-assigned to Africa which was then manned by 10,000 troops spread out between Cape Colony and Natal. Asked how many troops he thought necessary to garrison Natal against invasion from the Boer republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State, he replied 5000 and was given twice as many and a new commanding CO, General Sir George White.

Major-General Symon’s dying words were, “Tell everyone I died facing the enemy.” —Wikipedia photo

Known as a “fire-eater,” Symons, on his own authority, led a brigade to Dundee, 70 miles north of Ladysmith and situated in a triangle between the Boer states.

Unhappy with their exposed position, White wanted to recall them but was persuaded not to do so by the governor of Natal. On October 11, 1899 the Boers declared war and advanced upon Natal. Nine days later, at daybreak, they began shelling the town with 75mm cannon. Symons, annoyed by their “impudence” in beginning the attack before breakfast, had his guns return fire as he grouped his infantry in close order to advance.

Despite a lethal fire from a concealed enemy firing modern bolt-action rifles, the three British infantry battalions marched forward to some shelter in a small wood below the hill on which the Boers were positioned. Here, under continuing heavy fire and with a ditch, a stone wall and an open stretch beyond, the British stalled. Symons, accompanied by an aide-de-camp flying a red pennant, galloped up to demand they advance. Dismounting, he walked through an opening in the wall, still followed by his pennant, only to return almost immediately and ask to be helped to mount his horse. Once out of sight of the men in the front lines, he asked some stretcher-bearers for aid, saying he’d been shot in the stomach.

Rushed to the Dundee field hospital in excruciating pain, his only expressed concern was, “Have they got the hill?”

As it happened, the British had won the battle but their position at Dundee was untenable and, just days later, Brigadier General Yule, his successor, ordered a retreat to Ladysmith under cover of darkness. The most badly wounded, including Symons, were abandoned to the Boers and he died three days later, a prisoner of war.

His last words to a medical officer were, "Tell everyone I died facing the enemy, tell everyone I died facing the enemy." Among those who remembered him with respect and fondness was a young British war correspondent named Winston Churchill.

There appears to have been no protests against the monument to Symon’s valor in Victoria Park, Saltash, Cornwall, UK.

* * * * *

One more for today, another Victoria Cross holder who ended a distinguished army career as a field marshal: Sir George Stuart White (1835-1912) earned his VC during the India mutiny and in Afghanistan then fought in the third Anglo-Burmese War in 1886. By the time of the Second Boer War he was a lieutenant general in command of the British forces in Natal.

Lieutenant-General Sir George Stuart White is remembered for having held Ladysmith from the Boers during a four-month-long siege. —Wikipedia photo

The battle of Elandslaagte, Oct. 21, 1899, has been termed “one of the few clear-cut tactical victories won by the British” during the war, only to be thrown away. When the Boers, under General Johannes Kock, cut communications between the British garrisons at Ladysmith and Dundee by seizing the railway station at Elandslaagte, White ordered his cavalry under Major General John French to retake the station. Arriving at dawn to find that the Boers had two field guns, French wired Ladysmith for reinforcements which soon arrived by train.

After a short bombardment, in the gloom and driving rain of a thunderstorm, and facing the obstacle of a barbed wire fence, three infantry brigades and a detachment of dismounted cavalry assaulted the Boers’ left flank and soon occupied the enemy’s main position.

Even as some of his men began waving white flags, General Kock—“dressed in his top hat and Sunday best”!—led a counterattack.

At first the British faltered but, buoyed by a rousing chorus of a bugle and bagpipes, quickly rallied and drove them back. Many of the Boers were killed or wounded, Kock being among the fallen.

At this, the surviving Boers mounted their horses to retreat but were cut down with lances and sabres by two squadrons of cavalry in what’s said to be one of the few successful British cavalry charges of the war. The surviving Boers and the two field guns were captured.

In short, the short but vicious battle of Elandslaagte was a clear-cut victory for the British but General White, fearful that 10,000 Boers were about to attack Ladysmith from the Orange Free State, ordered French to retire. Two days later, the Boers reoccupied Elandslaagte and Kock died of his wounds.

It’s easy to criticize White’s decision to abandon Elandslaagte, isolated as it was and difficult to defend, in favour of the defence of Ladysmith where, for four months White’s garrison held out while making newspaper headlines throughout the Commonwealth. Although General Sir Redvers Buller (see above) always denied ordering White to surrender, that’s the way White, fellow generals and historians have interpreted his telegram.

Either way, White won immortality by responding, “I hold Ladysmith for the Queen.” And he did just that until the siege was finally lifted in February 1900.

Relief of Ladysmith. Sir George White greets Major Hubert Gough on 28 February 1900. Painting by John Henry Frederick Bacon. —Wikipedia

White finished his career as Governor of Gibraltar then as Governor of the Royal Hospital Chelsea.

* * * * *

As we’ve seen (so far), five of the generals who are commemorated by Ladysmith street names were nothing if not bigger than life but, like all of us, subject to human frailties. We have several more to go but we’ll do that another time.

That’s when I’ll tell you of the fascinating connection between a Boer War general, Ladysmith, B.C.—and a fascinating character known to us as Jack the Ripper!

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.