Melanope, the Witch of the Waves

Even in death a ship does not sleep soundly. Timbers creak in eerie symphony with wind and wave, nesting pigeons converse in dark corners, ghostly shadows walk decks and passageways where, once, seamen ran to their stations in weather fair and foul...

Her lofty masts, white sails and graceful bowsprit were long gone when I first set eyes on her, but the sleeping Melanope remembered the distant day when she was one of the most beautiful and fastest clipper ships ever to ply the seven seas.

The beautiful clipper ship Melanope, one of the fastest sailing ships of all time, ended her career as part of a Vancouver island breakwater. —www.Pinterest.com

By the 1970s she was derelict, her ravaged iron hulk standing watch with other seagoing ladies of the past whose skeletons formed the Royston logging grounds breakwater.

Quite unwittingly, her owners had been blessed with prophecy when they christened her, Melanope being derived from ‘melanic,’ which is translated from the Greek ‘melas, melanos’– meaning black, or belonging to a black class.

When, black she did become from years of carrying coal, Melanope already had a black past..

* * * * *

Built by W.H. Porter of Liverpool, the three-masted clipper ship was 256 feet of beauty and speed. Under full canvas, with a good breeze, the 1600-ton ‘witch of the waves’ could streak along at 13 knots.

What would become her legendary ‘curse’ began on her maiden voyage, England to Australia, with emigrants. While heading for the open sea, her officers found that not everyone aboard was a paid passenger. Still walking her gleaming decks, selling apples, was a ragged old woman. When an angry mate ordered her aboard one of the attending tugs, she indignantly refused.

Voice rising, the officer explained that she couldn’t remain aboard unless she bought a ticket. When the hag replied to this ultimatum in a very forthright—and not un-seamanlike—manner, the exasperated mate ordered his men to remove her bodily.

This task the husky tars proceeded to execute, bundling her over the rail in seconds.

But not before she’d delivered a curse; a curse that was said to have dogged Melanope for many years and earned her a reputation from which she never escaped.

It’s a great story but hardly the genesis of a jinx, one would think. Or maybe not...

The incident of the apple vendor was forgotten until, in the Bay of Biscay, a storm brought the clipper’s towering masts crashing to the deck. A jury rig soon had her limping back to port, where it was determined that she was over-rigged; a problem solved at some expense with shorter masts and a smaller sail plan.

Melanope began to go about her business quietly for the most part although, periodically, her name would be whispered in awe by superstitious seamen.

In fact, her notoriety was justified more than once as incidents of mutiny, murder and suicide haunted the lovely lady around the world.

One story involves a wicked captain and the naive daughter of a wealthy Indian merchant–or daughter of an Indian army colonel, depending upon the source. Melanope was serving as a honeymoon yacht after the captain eloped with his bride from Antwerp, bound for Panama, wrote famous marine historian Basil Lubbock.

The honeymoon, as he recorded it in his classic Last of the Windjammers, became a voyage into hell.

The crew, left to their own devices, broke into the liquor and went on a weeks’ long spree of revelry, fistfights and “part-time’” mutiny. When the drink-crazed master made an appearance on deck, it was to drive his men with a whip.

The orgy ended when the sodden bride died of malaria and a sobered captain buried her at sea. Days later, he leapt over the side; a victim of remorse, some said. Others hinted that he’d been helped by parties unknown. The first mate assumed command, sailing her to San Francisco then allegedly vanished with the captain’s money chest.

In 1930 Capt. Creighton Robinson, who subsequently commanded the Melanope for two voyages Down Under, disparaged Lubbock’s colourful account: “Basil Lubbock...gives some of her early history and latter-day usage with a lot of bunk in between particularly that pertaining to the purchase at Antwerp, etc.”

Explaining that Melanope’s owners wanted “a man with British license to take command,” he “took charge of her in ‘Frisco in the latter part of 1900...and took Kate [his] wife with me on [the] voyage to Sydney, Australia. [Melanope] was then rigged as a [barque] and poorly rigged in the way of running gear, at that...

“The story I got firsthand from Green, who was mate, was that the captain and his wife had purchased the vessel at Antwerp, intending to cruise around the world. On reaching Panama she died of fever. The captain also contracted fever of which he died en route to San Francisco.”

Capt. Robinson left the Melanope after two voyages, the first to Sydney and back to the Bay City in the remarkable time of 110 days.

But Melanope has another tale of terror involving a captain and his lady. This time the master supposedly had an affair with an attractive young, married and rich passenger. The lovesick woman remained aboard when Melanope reached Australia where she bought a return ticket to be with her paramour.

This cozy arrangement lasted through several voyages until the captain wearied of her and refused her passage. An obstacle she overcame by buying the ship outright.

When the crew heard gunshots in the master’s cabin they found the couple dead; murder and suicide was the verdict.

(This tragedy was recalled years later when a gold bracelet was found hidden in in the upholstery of one of the ship’s chairs.)

On another occasion two seamen hacked each other to death with knives.

After Capt. Robinson it was the turn, in 1902, of Capt. N.K. Wills, later a noted Pacific Northwest mariner and ship’s pilot who died in Vancouver in the 1950s. Prior to his posting to Melanope, he’d commanded the Dollar Company’s steamship Arab, ferrying troops and supplies to the Philippines during the Spanish-American War.

Bad luck and near-disaster were to this Cornishman’s lot, too.

Bound for Cape Town from Port Townsend with lumber in 1902, he rounded dreaded Cape Horn without incident. But when he berated his helmsman’s handling of the wheel, the man presumably made come comments of his own and Wills had him placed in chains for insubordination.

When all but a half-dozen hands and two of his mates refused duty to protest his punishment of the helmsman, Wills whipped out a pistol, armed his mates with clubs and coolly proceeded to shackle each and every mutineer.

Then, with only eight loyal officers and men, Melanope streaked the remaining 5,000 miles in 19 days. Melanope’s record, achieved under handicap, was never beaten.

Wills docked the mutineers all the expense of hiring men to unload the ship then had the satisfaction of seeing them sentenced to six months’ hard labour on a breakwater.

Melanope’s last voyage under sail was almost disastrous. Wills’ wife and children were aboard in December 1906 when a gale caught her in ballast, stripped her sails, snapped her masts and forced the crew of 22 to abandon ship. They were rescued by the lumber schooner William H. Smith and landed in Port Townsend.

Melanope was later found drifting on her beam end off the mouth of the Columbia River Bar and towed into harbour, the only living soul aboard, the ship’s Scotch terrier.

Ironically, she was towed to safety by a vessel thought to be the S.S. Northolm which met her own violent end off the northern end of Vancouver island in the 1940s.

Because the Wills family had lost most of their possessions in the wreck, the captain joined the pilotage in Seattle. As for Melanope, it was the beginning of the end. While she’d continue in service for many more years it would be in the lowly work of a coal tender.

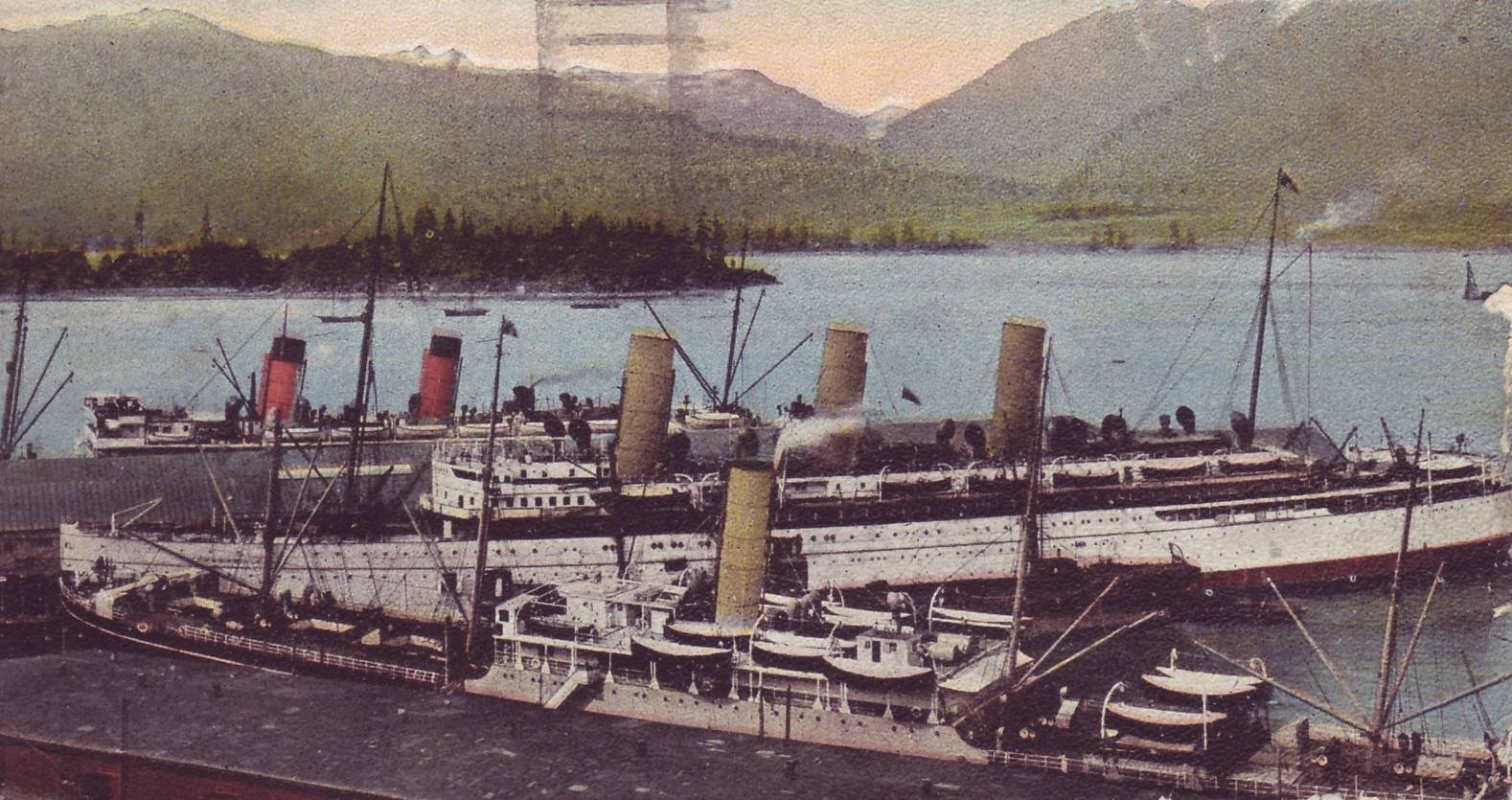

For years, the former speed queen served as a coal barge to the CPR’s famous Empress and Princess fleets. —Author’s Collection

Never again would the witch of the waves shatter records under billowing sail.

Bought by Seattle mariner Capt. James Griffiths, Melanope suffered conversion to a barge in 1913. Her tall mainmast was removed although she kept her fore and mizzenmasts for another 20 years. Her once-gleaming hardwood decks were ripped up, her bulwarks raised.

Then sold to the CPR, she spent a busy middle-age coaling the famous white Empress ships and coastal Princess fleet. During the First World War she served as a tender to British and Japanese warships and vessels of the U.S. Coast Guard in Alaska. Her deliveries of Ladysmith and Cumberland coal were usually under the command of Capt. Peter Farrell, of Vancouver, his family and a four-l\man crew.

Steam tug Nanoose, Ladysmith’s famous Transfer Wharf in the background. —Author’s Collection

Astern of either of the steam tugs Qualicum or Nanoose, Melanope wnt about her her dirty task uncomplaining. Her curse seems to have lifted at last, other than the day a crewman fell to his death in a hold.

Finally came retirement for the aging queen; she was sold to join the chain of dead ships in Crown Zellerbach Logging Co.’s Royston breakwater.

Broken apart by decades of storms, Melanope’s stern in the Royston breakwater. —Author’s Collection

She’s there today, deep in the mud and broken in two by three-quarters of a century of sou’-easterlies which roar across the Strait of Georgia. After the Second World War her old compatriots, Qualicum and Nanoose, joined her in the Royston death watch.

Like her fellow tug Nanoose, S.S. Qualicum ended her days with Melanope at Royston. —Author’s Collection

Occasional visitors would gaze curiously at her twisted wreckage and ponder her identity and career. One visitor who remembered her well was Bruce M. Watson who wrote of the once-proud queen of the seas in a Vancouver newspaper:

“As a boy in Royston, which wasn’t too long ago, I used to row around the many breakwater hulks, some as late as Second World War vintage, and climb over them looking for unsalvaged pieces which could give me a glimpse of their past.

“One that presented endless fascination was the Melanope, then in a sad state as it had a gaping hole in the waterline.

“Through this hole, when the tide was right, I could lean inside and view in the misty interior the changing patterns of light produced by sun-rays poking through the rotting planking and open mid-section. The exposed ribs were webbed with strings of seaweed beaded with water droplets and the light glistened from these, the rusty spikes, the rippling water of the flooded area, and the dripping water from the fallen beams.

“It was an eerie and haunting sight. Occasionally birds found places to make their nests, in the soft rotted wood well above the waterline.

“And so the Melanope died on some mudflats at Royston, not a very fitting death for a ship of such illustrious reputation but, I assure you, it did so in a most tranquil setting.”

* * * * *

Many a visit I made to Royston in years gone by, when, with permission of Crown Zellerbach who commissioned me to record the histories of the ships that form the breakwater, I was able to not just view them from a distance, but allowed to clamber in, around and over them at my pleasure.

Sadly, there was less to see each visit to the noble ships that ended their careers here. The breakwater no longer serves its purpose of protecting log booms and decades of storms and back-filling by bulldozers have all but buried most of them in sea mud and rip-rap.

* * * * *

Was it Farley Mowatt who once said, “Never let the facts get in the way of a good story”?

We’ve already seen that Capt. Robinson, one of Melanope’s masters, dismissed the account of Basil Lubbock, “miner, sailor, soldier, writer,” of the apple vendor’s curse.

At the further risk of spoiling a great story, I must add Wikipedia’s voice which begins by introducing Lubbock (1876-1944) as a British historian, sailor, soldier and a prolific writer “on the last generation of commercial sailing vessels in the Age of Sail. He was an early (1911) member of the Society for Nautical Research, served on its council (1921–24) and contributed to its journal, The Mariner’s Mirror.”

So far so good but, alas, it doesn’t end there. Lubbock’s legacy is judged harshly: “Lubbock is not regarded as a completely reliable source as a historian. His books had no footnotes or bibliographies, as was common at the time.

“He relied on correspondence and interviews with captains and crewmembers, rather than documents and fact-checking. He sometimes confused the names of ships and captains, or gave incorrect dates. However, Lubbock's correspondence and interviews are themselves a unique source.

“Some of his books are still in print and their contents are often quoted by others. His book, The China Clippers, was an inspiration for All the Tea in China by Kyril Bonfiglioli.”

There you have it: Melanope the legend or, perhaps, Melanope the myth. Whichever is the case there’s no denying her deserved accolade as the “Witch of the Waves”. I feel privileged to have actually seen her even if by the time I did so she was a broken derelict.

Col. W.D. Symons, left, longtime manager of the Maritime Museum of British Columbia in Victoria, is photographed with the Melanope’s wheel behind him. The same wheel whose mishandling by a helmsman provoked the clipper’s mutiny. —Author’s Collection

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.