Murder On the Parade Square

The demolition, several years ago, of the 1890 Officers’ Mess and Quarters at Work Point, Victoria, inspired a letter to the editor of the Times Colonist warning against disturbing its two resident ghosts.

A walking tour in 2004 of the Work Point Officers’ Mess and Quarters shortly before its demolition. —Author’s photo

The writer was referring to the spirits of a Major Steinberg and a four-year-old boy.

Indeed, the former Esquimalt army base should be haunted–by the spirit of Captain Peter Elliston. The commanding officer of No. 5 Company, Royal Canadian Garrison Artillery met eternity at 9:25 on the morning of Monday, Aug 1, 1910, moments after he’d begun his daily rounds.

Capt. Peter Elliston, shot down on the parade square. —Colonist

That’s when 34-year-old Gunner Thomas ‘Paddy’ Allan, who’d for weeks nursed his hatred for this officer who’d given him 21 days’ detention for drunkenness, made good his vow: “I’ve a bullet for him and it will find its billet.”

As indeed it did.

* * * * *

That morning, refused a drink by Bombardier W.B.D. Corrigan, Allan had threatened to “burst” Corrigan’s stripe from his arm. After declining Corrigan’s invitation to go behind the barracks and “have it out, now, with bare firsts,” he repeated his oft-voiced grudge against Elliston that “he hasn’t treated me right, he did me an injustice.”

Paddy had then vowed: “I’ve a bullet for him and it will find its billet.”

Gunner Paddy Allan. —Colonist

Instead of reporting this alarming threat, Corrigan dismissed it as just more of Allan’s bluster and turned his thoughts to a fatigue party which had been assigned to whitewash a barrack wall. It having become common practice to “joke with” Allan because of the state of his nerves, Corrigan said he’d assign Allan the highest position on the staging, ordered the men to draw the necessary tools and supplies from stores, then headed for the lavatory.

At which Allan left the others and returned to his barrack room.

From there, through the open window nearest his cot on the second floor of the enlisted men’s No. 2 Company Block, he’d watched as Elliston entered the building containing the company office, shops and stores.

Paddy saw Elliston leave his desk and stand near that of Sgt.-Maj. Farley. Any time now, the captain would step outside. Taking his Ross rifle from the wall-rack, he loaded one of four .303 cartridges he’d secreted away during target practice, cocked the rifle and, resting the heavy stock on the window sill, took aim and coolly squeezed the trigger.

After firing a single shot, he dropped the smoking gun on the floor, descended the stairs and crossed the square to where Elliston, who’d clutched at his throat then managed to stumble several yards before falling, lay mortally wounded in the arms of Sgt.-Maj. Askey.

The bullet had entered just below his left ear and exited just below his right, severing his jugular vein.

Unaware that Allan was the shooter, those who’d rushed to Elliston’s side made no attempt to stop him as he gazed down at his victim then turned on his heel and walked through the main gate and off the base. But, instead of attempting to escape, he proceeded to the nearby St. George’s Inn and ordered a brandy, for which he had no money, then asked to lie down because he wasn’t feeling well. However, after only a few minutes, he left.

For base officers who’d known nothing of Allan’s threats, and no thanks to witness Bryan, the discovery of his just-fired rifle on the barrack room floor where he’d flung it was the first clue to the killer’s identity.

By this time the police were on hand and, after distributing typewritten handbills giving Allan’s description, joined the manhunt that was already underway. “Through gardens and over fences,” reported the Colonist, “the searchers harried the countryside,” almost scaring the life out of an innocent gardener who suddenly found himself surrounded by soldiers with levelled rifles.

The newspaper had no doubt that Allan’s vengeful former comrades were determined to take him, dead or alive.

When, three hours later, Gunner Smith and Bugler Trimbey spotted his blue overalls in a thick stand of shrubbery opposite the George Inn, they approached with rifles cocked. “Don’t pull the trigger,” cried Allan who was described as being in a state of near collapse. Nevertheless, upon being handed over to the police, he was handcuffed and leg-ironed.

After asking for a drink of water he was taken by buggy to the provincial police office where a search of his pockets turned up a few coins and three live .303 cartridges.

* * * * *

After being warned that he was being charged with murdering Capt. Elliston, he denied having meant to kill him: “I only intended to maim him. I am sorry I killed him, but he has used me very mean at different times. I might just as well be dead as suffer this way. My health is awful poor. I am in misery all the time. Too much drink is all the cause.”

Asked if he’d used dope, he said, yes, “just the common kind,” possibly a reference to opium.

Gunner Allan as a prisoner. —Colonist

His expressed regret for having killed Elliston seemed hollow when it was reported that, upon his being lodged in the provincial jail, he told a guard that he wasn’t sorry. This seems to contradict a later news account that declared him to be in a state of nervous collapse since he realized that he faced the gallows after a jailer informed him that Elliston had died.

Prison physician Dr. J.S. Helmcken prescribed him a bromide.

Dr. J.S. Helmcken treated Allan for his nerves. —Wikipedia

He did indeed face possible hanging, a coroner’s jury having ruled, in words that seem almost quaint today: “At Work Point barracks on First day of August, 1910, one Thos. Allan, a gunner in No. 5 Company, C.R.G.A., did wilfully, feloniously and of malice aforethought, kill and murder...Peter Elliston by shooting him with a rifle against the peace of our Lord and King, his crown and dignity.”

* * * * *

How do we know this deadly sequence of events in such minute detail? Is it all surmise, a reconstruction of events based upon circumstantial evidence and Allan’s repeated threats to shoot Elliston?

Incredibly, or so it seems, there was an eyewitness to those few minutes after Allan left the work detail, returned to his barrack room, loaded his rifle, rested it on the window sill and waited for Elliston to step out onto the parade square!

In No. 4 barrack room that he shared with Allan, an unbelieving Gunner James Bryan had watched, mystified, as the tragedy had unfolded in the reflection of his shaving mirror!

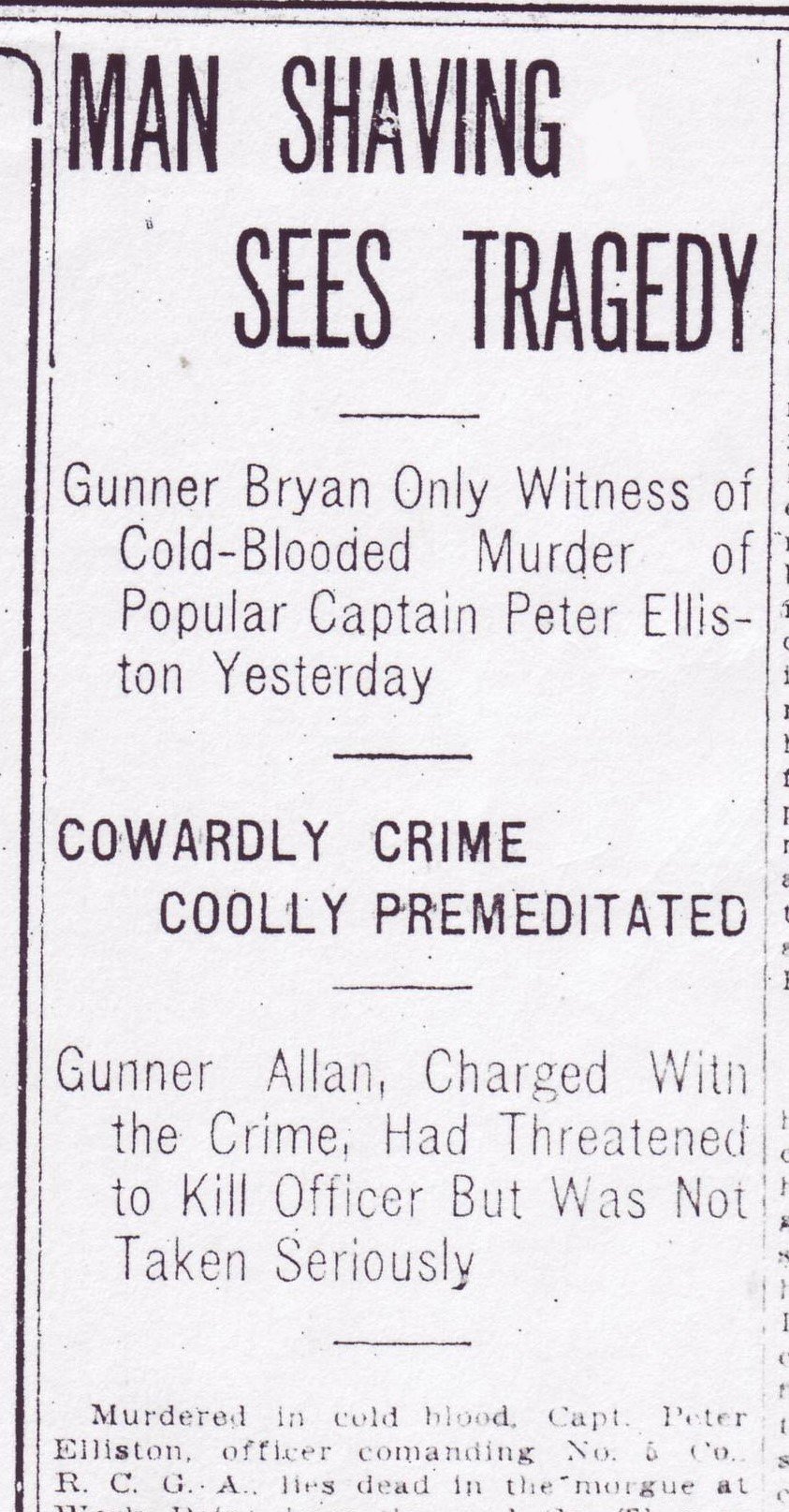

As this front-page headline of the Colonist states, there was an eyewitness to Capt. Elliston’s cold-blooded murder.

He later claimed that it all happened very quickly, that Allan suddenly grabbed a rifle from the rack (the foresight on his own weapon was out of alignment), went to the window and fired a shot. At what, Bryan said he didn’t know until he he silently followed Paddy downstairs and watched him cross the square to view Elliston’s body then leave the base.

Instead of reporting what he’d seen, he said he was so shocked that he only told three gunners that Allan “had fired a shot” —but didn’t identify him as the killer until after his arrest.

The Colonist found Bryan’s inertia to have been as amazing as Paddy Allan’s “cowardly [and] coolly premeditated” murder. Its words drip with accusation and outrage: “No alarm was given by the witness of the tragedy. Not a sign did he vouchsafe for nearly three hours that he had witnessed the tragedy. He took part in the hue and cry after the fugitive murderer who went out of the barrackyard and took flight and not until the [police] officers were questioning those who were in the vicinity did he tell of having seen the tragic happenings reflected in the mirror....”

Not surprisingly, Bryan was arrested by military police.

As seen, Bombardier Corrigan had shrugged off Allan’s vow to shoot their commanding officer as no more than his being bitter and hung-over. However, upon hearing a shot while he was in the lavatory, which was just to the east of No. 2 Block, Corrigan instantly surmised what had happened—but “waited a few minutes” lest he be Allan’s next target.

(Curiously, after Elliston had been removed to the base hospital, Corrigan went to the barrack room and removed the fired cartridge from Allan’s rifle. He didn’t offer to explain his action and appears not to have been asked why.)

Although mystified by the artillery men’s apparent lassitude and reticence, police found it easier to understand Gnr. Allan’s act of revenge. A career soldier and crack shot who’d served for 11 years in a British regiment in South Africa, India, Jamaica, Malta and Halifax, he’d once been a colour sergeant. Since joining the Canadian army four years earlier, he’d served in the military police, the engineers, the service corps, as a sapper and, finally, with the common rank of gunner in the artillery.

This, because, at least once, his use of alcohol and drugs had put him in the barracks infirmary. The Colonist declared him a confirmed drunkard with a long “crime sheet”. In fact, so bad had his nerves become that–contrary to his steady hands on the morning of August 1st–he sometimes shook.

Four months earlier, he’d faced a court martial. On June 11th, when he was again charged with drunkenness, Capt. Elliston had exercised what was described as “the utmost leniency” in sentencing him to 21 days’ detention in the guardhouse. Despite his having been released after serving only 11 days, thanks to a general pardon having been decreed upon King George V’s accession to the throne, Allan had made repeated threats “to do for” Elliston.

Sadly, as noted, he hadn’t been taken seriously by his comrades. They’d laughed at his threat, told him he was “getting the rats [DT’s],” or “the dope’s working on you again, laddy”.

(Coincidentally, Paddy Allan shared the front page with one of the most remembered British murderers of all time, the Colonist also reporting that wife-killer Dr. Hawley Crippen and his lover had been arrested aboard a trans-Atlantic steamship.)

YESTERDAY’S TRAGEDY

“The murder of Captain Elliston yesterday was a severe shock to the community in which he was held in universal esteem. He was a fine type of a soldier and a gentleman, popular with the whole garrison as well as with all others who had the pleasure of knowing him. He was an excellent citizen in every sense of the word, and it is a most melancholy thing that so useful a life should have been cut off through the act of a man who by long dissipation had debased himself physically and mentally.

“It was a horrible crime, a dreadful act which for absolute lack of justification or excuse it would be difficult to parallel. We can do a little more than place on record our appreciation of the virtues of the murdered man and an expression of detestation of the crime of which he was the victim. It is to be assumed that there will be a searching investigation into all the circumstances leading up to the crime. By this we mean something more than a trial by jury. It is dreadful to contemplate the fact that an officer in the discharge of his duty should be shot dead while crossing the barrack yard.”

—Editorial, The Daily Colonist, Aug. 2, 1910

(It’s interesting to note that Capt. Elliston isn’t interred in the Veterans Cemetery, Esquimalt, but in Cedar Hill Cemetery with his wife Susan Georgina, 32, who’d predeceased him just nine months before. His military funeral was said to be one of the largest ever held in Victoria.)

St. Luke’s Anglican Church, Cedar Hill. —Old Cemeteries Society of Victoria

* * * * *

One of the greater ironies of this tragedy was that Allan’s vaunted marksmanship, which had twice saved his army career, and by which he was able to gun down Capt. Elliston from almost 300 yards distant for having denied his request to buy himself out of the army, had, in his words, failed him.

We’ve seen that, in his confession taken shortly after his arrest, Allan said he’d only meant to maim Elliston. Saying that he hadn’t eaten in nine days because he was ill–“I am in misery all the time; too much drink is all the cause”–he expressed regret that Elliston was dead, “but he has used me very mean at different times”.

With such a seemingly open-and-shut case, Allen was arraigned for trial in October. Gunner James Bryan remained in custody, the Crown having expressed the fear that he might flee rather than testify against his friend.

Bombardier Corrigan wasn’t to be found—he’d deserted rather than, it was thought, have to explain in court that he’d ignored Allan’s threat to shoot Elliston.

At his trial Allan took the stand to claim temporary insanity as a result of alcoholic dementia. When convicted and sentenced to hang, he ate and said little, and nervously paced his cell. As December 2nd, his date with the hangman neared, a petition was circulated asking that his sentence be commuted to life imprisonment. Instead, Allan was granted a new trial—on the grounds that the Crown prosecutor had possibly misled the jury to believe premeditated murder.

He’d done this by attempting to introduce in court, through another witness, Corrigan’s testimony at the preliminary hearing that Allan had threatened to shoot Elliston. Because the vanished Corrigan wasn’t available for further testimony or rebuttal, defence counsel’s objection was upheld by the judge.

But—had suspicion of premeditation been planted in the minds of jurors? In a split decision, the Supreme Court ruled that Allan had been denied a fair trial.

Again convicted, this time of manslaughter, he was sentenced to 20 years. Luckily for him, not until May 1912 did his duffel bag turn up during a cleanup of the Work Point barracks. In his own distinct scrawl, the diary was filled with innocuous rants against army life, But there was something else: Gunner Paddy Allan had clearly outlined his plan, not to maim, as he later claimed, but to kill Capt. Peter Elliston.

According to the late Cecil Clark, former deputy commissioner of the B.C. Provincial Police, Paddy Allen spent his last years in Vancouver, hawking newspapers on a downtown street corner.