Nanaimo Was the End of the Trail for Klondike Killer

Conclusion

As we’ve seen, to Joseph Camille Claus of Nanoose Bay goes the dubious honour of committing “the first cold-blooded premeditated murder...in the frozen north,” in this case the Stikine River country.

The mighty Stikine River where gold seekers risked life and limb in 1898 has become a tourist Mecca. —peakadvisor.com

According to the Victoria Colonist, anyway. Claus, it should be noted, had yet to face trial let alone be convicted by a jury of his peers.

But the circumstantial evidence, so far as was known in Victoria in the spring of 1898, was pretty damning. The bodies of Claus’s prospecting partners, Charles Hendrickson and James Burns had been found axed and shot to death, and a man matching Claus’s description had been seen fleeing the scene.

Just a month before, the partners had left Nanaimo to seek their fortunes in the Klondike gold rush. When Claus alone returned to Nanaimo, it was to stand trial and, if found guilty, face a hangman’s noose.

* * * * *

As we’ve seen, communications between the northern wilds of Stikine River and Victoria had been confusing and contradictory, particularly the nailing down of the correct identifications of the various parties involved. At one point it was thought that Claus was one of the victims. But—amazingly under the circumstances—B.C. Provincial Police Chief Constable William Bullock-Webster soon had the matter—and Claus—in hand.

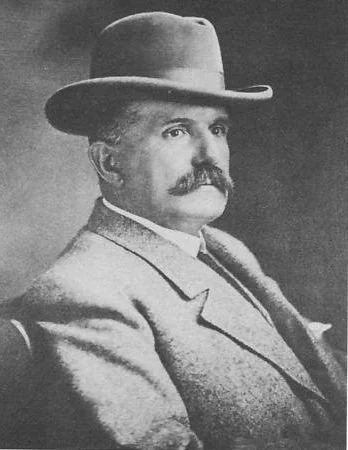

B.C. Provincial Police Chief Constable Wm. H. Bullock-Webster had a land surveyor named Brownlee take this photograph of Claus who’s described as being “in double irons...sitting in front of a cell”. You can just see the manacle on his right wrist. —BC Archives

Known to have been near penniless, he was carrying four $100 bills, two $50 bills, a $20 gold piece, gold valued at $85, and some silver. He attempted to divert suspicion from himself with a flimsy story about a stranger named Brandy, saying, “I would murder nobody if they treated me right.” He admitted to having mortgaged his farm to go to the Klondike and said that he regretted having left home.

Then he said that Hendrickson had gone berserk and attacked Burns with an axe while in their tent. He, Claus, had shot Hendrickson in self defence—four times, because the gun smoke was so thick he could hardly see, and Hendrickson just wouldn’t go down.

Perhaps overwhelmed by the evidence against him, Claus then confessed to Constable Jackson that he’d deliberately killed both men. He regretted having slain Burns, but had no remorse for Hendrickson: “If I had not done it to him he would have done it to me.”

Under normal circumstances Claus would have been tried at Glenora, but legal problems, transient witnesses eager to move on, and, in particular, the lack of registered voters in the district, precluded a jury being empanelled there. So the trial, for the murder of Burns alone (leaving that of Hendrickson in reserve should Claus not be found guilty), was moved to Nanaimo from whence the six partners, Claus, Burns, Hendrickson and the three Vipond brothers had set out for the Klondike just two months before.

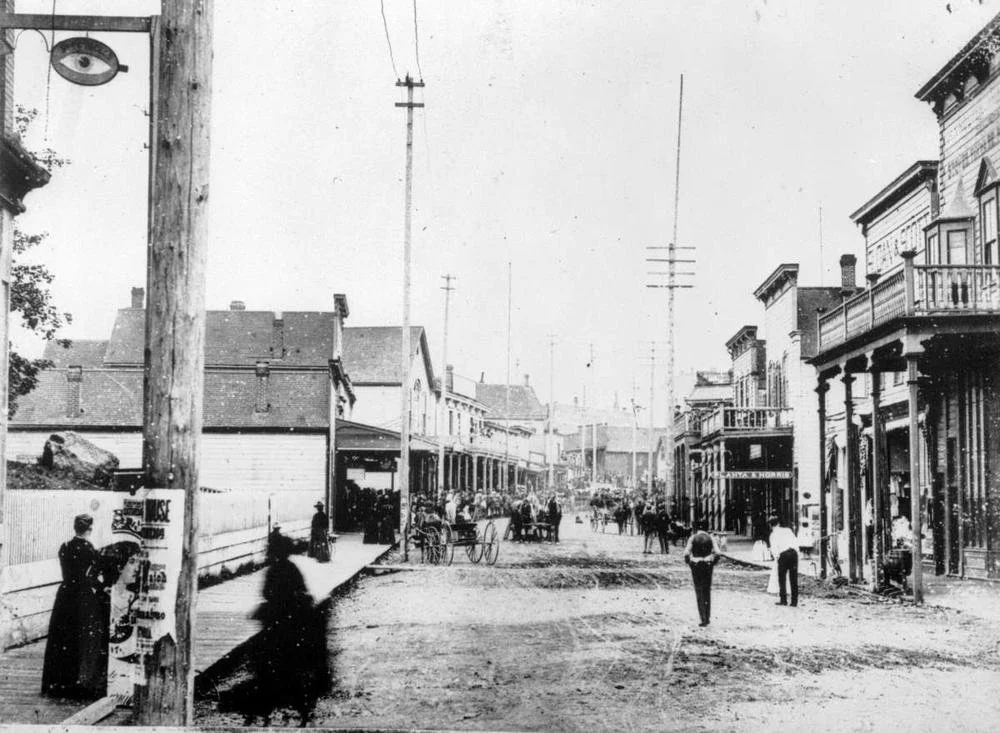

What began in Nanaimo as an expedition to the Klondike gold fields ended in Nanaimo—in a jail cell. —BC Archives

How fortunate for the Viponds that they’d chosen not to travel farther with the accused slayer. Perhaps, in so doing, they’d saved their own lives. For that matter, Claus might not have dared to attack Burns and Hendrickson had they remained.

Whatever the case, it now remained for a jury of Nanaimo miners and merchants to determine what really happened on the snow-bound trail of ‘98.

Alex. McDonald identified the prisoner as the man he saw on the Teslin trail on April 6th, the day after the murder was committed. The prisoner told him he’d left his partners, Burns and Hendrickson, down the trail portaging their outfits and was anxious to know how far it was to the snow.

Constable Malcolm McLean told of searching the crime scene, finding several papers and a bank book containing $140 belonging to Burns in the water, along with his gold watch and chain. “Several other articles had been sunk in the river by rocks.” He’d then started in pursuit of Claus and arrested him about 68 miles from Telegraph Creek.

Despite his cautioning Claus that anything he said could be used in evidence against him, Claus, after trying to place blame on someone named Brandy, admitted to striking Burns with an axe, shooting Hendrickson four times and hiding their bodies in the ice.

Constable Jackson testified that Claus, asked if he was sorry for what he’d done, replied, “Yes, for Burns, but not for the other man. If I had not done it to him he would have done it to me."

Claus then asked, "Did you see the poor boys? They looked awful bad,” as his eyes filled with tears and he bit his lip nervously.

Dr. Carliyle’s testimony of holding a post mortem examination and his description of the fatal wounds concluded the case for the prosecution. No witnesses were examined for the defence.

On June 30, under the headline CLAUSS [sic] GUILTY OF MURDER, the Nanaimo Free Press reported that Crown prosecutor H.A. Simpson “delivered a very strong address to the Jury, and Mr. Fred McB. Young followed with an able address on behalf of the prisoner. After the Jury had received a lengthy charge from the Judge, they retired, and returned in about an hour and a-half with a verdict of ‘Guilty.’

“The judge addressed the prisoner and said the case gave him pain to pass the death sentence, but that he had no alternative. The Prisoner was asked if he wished to say anything before sentence was passed, and with bowed head and tears rolling down his cheeks, all he had to say for his atrocious crime was: ‘I didn't understand well. I don't know what to say. I am sorry—very sorry, I put the bodies under the ice. I did not know what I was doing.’"

In the galleries, women spectators joined him in “weeping bitterly” as he was sentenced to die on August 2nd.

While awaiting execution, Claus spent his time reading French newspapers (and eating heartily, one guard would later note). Usually in good spirits, as time passed, he turned more and more to the Bible. He had little to say to his keepers, other than to ask the time, although he did speak at length to B.C. Police Supt. Fred Hussey. His only official visitors were his wife, his lawyer F.B. Young and the Rev. C.E. Cooper.

Upon conviction, Claus had little to say but did speak at length with Superintendent of B.C. Police Frederick Hussey. —BC Archives

On August 11th, barrister and solicitor Fred McB. Young, identified here as Yarwood Young, wrote Attorney-General D.H. Eberts, Q.C., regarding his client, Joseph Claus who, “convicted of murder at the Special Assize held here on the 29th June,” was to be hanged less than a week hence.

Young was writing on behalf of Mrs. Claus who’d “expressed a strong desire to obtain possession of the body after execution. She has requested us to obtain if possible, your permission to this end. Will you therefore please advise us as early as possible if her request will be granted, as it will be necessary to make arrangements for his burial.”

That same day, Deputy A-G Smith received a query from H. Hauton, District Registrar, concerning the estates of Burns and Hendrickson, deceased, and that of the about-to-be deceased Claus.

After acknowledging the receipt of $412 and vouchers for disbursements paid by Bullock-Webster, Hauton informed Smith that defence counsel Young had made it known to him that he did not think that Claus’ estate should be charged for “the items for the coffins and digging the graves of Burns and Hendrickson:

“I would be pleased to be informed on what basis you would advise me to pay Mr. Young. I have Claus’ order to pay him all his money in my hands including his share of the $412.00. Please return the account when writing.”

It’s one of those finer points of law and the tidying up of Crown business that seldom meets the public’s eye. Was it Crown policy, 125 years ago, to charge an executed felon’s estate for victims’ coffins and grave-digging?

Within a week of execution, his automatic appeal to Ottawa for a commutation of sentence having been rejected, he complained of cramps, then became violently ill and suffered several seizures. As it turned out, despite two daily searches of his person and his bed, he’d managed to acquire strychnine and, within four days of his execution, he died by his own hand.

His last words were an apology to his wife and five-year-old son.

* * * * *

How in heaven’s name, asked the Free Press, did Claus acquire poison?

Claus’s death cell in the Nanaimo jail would have been smaller and cruder than this 1950s shot of Victoria’s Wilkinson Road jail by the Ryan brothers, but the bars and depressing atmosphere would have been similar. —BC Archives

A coroner’s jury charged with investigating the matter was as mystified as anyone else: “We, the jury empanelled to inquire into the cause of the death of Joseph Camelie [sic] Claus, find that he came to his death by a dose of strychnine administered by his own hands, but how he came in possession of the same there is nothing to show, as the evidence proves that every usual precaution had been taken by the officials in charge.

“THOS. KITCHIN, Foreman.”

Jailer John Degnen, identified as “the death watch,” had testified that he’d been on duty, Saturday morning about 4:00, when he heard Claus “breathing very heavily. I then heard him give a kick and thought he was dreaming. He had a severe shock and I then reported to Chief of Police Stewart and called him in.

“I took Claus out of the cell and seated him in a chair. Claus said, ‘Hold me hard.’

“He did not say what was the matter with him, and I did not ask him. [He] said ‘his heart was broke.’ He did not say he had taken anything. I sent for the doctor because we thought he was sick. I have no reason to believe what made him sick. I do not know how long he was sick before we sent for the doctor.

“He did not act as usual that night. He read the Bible and did not take his trousers off. I believe he was awake all night..”

Returned to his cell, Claus asked for and was given a drink of water. From his position, Degnen could “see up to his shoulders but could not see his head” and watched him enter the water closet. When he was inside the toilet was the only time that Claus was completely out of his sight.

In answer to a question posed by B.C. Police Supt. Frederick Hussey, Degnen said that Claus had read his Bible, Friday evening, even taking it to bed with him and reading for another hour or two, which was out of habit for him.

At four in the morning Claus asked the time, said it was getting late, then continued reading the Bible and a French language newspaper. “He made no complaint of being unwell. I heard him in the water closet. He had his pants on. He was only in the closet a short time...after [which] he went to bed.

“I was sitting near the steam heater and was not in a position to see his face. I carried the water to him and he took just a mouthful while lying in his bed. About 10 minutes after taking the water he commenced to breathe heavily. He never complained to me but grew worse and I called [Nanaimo police chief] Mr. Stewart.

“He repeated, ‘Hold me hard for cramps are coming on...’ Claus suffered very much from contraction of the muscles of the arms and legs.” (This is a typical effect of strychnine poisoning—Ed.)

To a juryman: “No one outside of the officials used the closet while I was on watch.”

Fellow gaoler J.W. Webster testified that only jail officials had had contact with Claus during his watches, Claus had never given him any hint of committing suicide, had talked on “general subjects,” and been in good spirits other than when he spoke of “the case on the trail,” which made him break down and cry.

F. English, another guard, also said Claus had given him no reason to suspect suicide. He’d wondered why Claus always slept in his undershirt and pants and he hadn’t seen him reading the Bible.

According to guard Kenneth A. McLean, only Rev. C.E. Cooper, Bishop Perrin and Father Durrand visited Claus on several occasions. He saw nothing pass between them other than, in the case of Rev. Cooper, “a picture of our Saviour,” but said that it was possible for any of them to have done so without his noticing. As for lawyer F.B. Young, he wasn’t given access to Claus’s cell as were his spiritual advisers.

That left Claus’s one other visitor, his wife, Marie. She, like lawyer Young, had to speak to him while seated several feet away with a wicket between them. McLean was sure that had she or Claus raised their arm to pass or to receive something, he’d have seen it.

McLean said Claus “was usually pretty cool” and had wondered aloud why he had to wait for Young to bring a deed from him to sign, or why he should wait for the inevitable decision from Ottawa to proceed with execution. This indicated to McLean that he was planning to kill himself and McLean so informed Chief Stewart and Sheriff Drake.

When, in fact, Ottawa ruled that the execution proceed, McLean noticed that Claus all but discontinued reading his Bible.

Marie Claus declared she last saw her husband three days before his death. She said she took nothing to him and spoke to him through the wicket. “I knew there was no hope for him then,” they didn’t discuss it and he seemed to be in good spirits. They spoke in French, he said nothing about committing suicide, and she was “very much surprised” when one of the Viponds told her that he was dead, likely from taking strychnine.

She admitted to having carbolic acid and laudanum in the house but “when the trouble came on,” she gave them to a neighbour “because I was feeling pretty bad over the trouble. I also gave her a razor to take care of because I thought it was too dangerous.

“I never knew my husband to buy strychnine or use any... I have no idea how [he] procured the poison.”

After hearing from Drs. McKechnie and Drysdale, Chief of Police Stewart, Sheriff Drake and Claus’s defence counsel F. McB. Young, the jury deliberated and ruled that there was “nothing to show” how he obtained strychnine.

And on that inconclusive and unsatisfactory note ends the case of Joseph Camille Claus, murderer. As expressed by the Free Press in its final report on his suicide, It Is Still A Mystery.

Stikine River country was wild, rugged and definitely off the beaten track until the Klondike gold fever of 1898 prompted six partners to set off in search of fortune. Three came home but two ended up murdered, the third a suicide. —Wikipedia

Millions upon millions of words have since been written about the last of the world’s truly great gold rushes. First, in the newspapers of the day, then in popular magazines, followed by books, movies and television. Bank clerk and poet Robert Service achieved his own fame and fortune by romanticizing some of its semi-fictional characters, and Jack London’s The Call of the Wild became a literary classic.