Nanaimo Was the End of the Trail for Klondike Killer

Part 1

If it seems to be a long way from remote northwestern British Columbia’s Stikine River and the Yukon-Alaska border to Nanaimo, mid-Vancouver Island, it is.

But no greater than the fabled long arm of the law, as was amply shown in June 1898 when 12 good citizens took their places in the jury box in a Nanaimo courtroom.

Stikine River glacier, 1908. —Wikipedia

They were there to try Joseph Camille Claus, accused of murdering his prospecting partners Charles Hendrickson and James Burns. As it happened, the trial’s taking place in Nanaimo brought the case full circle–three of the ill-fated party were from the Hub City and Claus was from nearby Nanoose Bay.

Just months before, like 10s of 1000s of others from around the world, they’d been fired with the common dream of making their fortunes in the Yukon. Newspapers were filled with stories of those who’d struck it rich—why not them?

Instead, Hendrickson and Burns ended up shot and bludgeoned to death and Claus faced a hangman’s noose for their murders.

* * * * *

In popular perception the Klondike excitement of the late 1890s ranks with, even surpasses, the momentous discovery of gold in California half a century before. Several smaller rushes followed that of 1849-, but none, not even our own Cariboo, 1861-, held the same allure as the call of gold from virtually unknown Yukon Territory. Until then, undervalued as only a source of furs for scattered Indigenous peoples and a handful of Russian and American trappers and traders, it was little explored and of even less interest.

That changed overnight upon news of the discovery of gold in Rabbit (soon renamed Bonanza) Creek, a tributary of the Klondike River. Newspaper headlines trumpeting ‘Gold! Gold! Gold!” triggered a stampede that literally stopped traffic in the streets.

Soldier, sailor, tinker, tailor—none, it seemed, could resist the siren call from the all but unknown northland. No matter that some couldn’t even find it on a map—it promised El Dorado! a chance for any man capable of hoisting a pack on his back and of working a pick, pan and shovel to escape a life of mostly unrelenting menial labour to retire in early comfort. Why, even a woman, were she hardy enough, could transform her life.

All they had to do was get there!

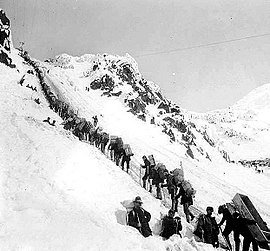

And so they set out, legions of them, overland and by sea, heading for the gold fields by any means available. Those who could afford it went by steamship up the Pacific coast from San Francisco, Seattle and Victoria to Wrangell and Dyea, Alaska from whence they braved the infamous Chilkoot or White Pass to Dawson City.

For those who could afford the fare, passage by steamship was the quickest way to the new gold fields. —Seattle Public Library

Most, however, upon landing in Wrangell, AL were faced with hauling their outfits on their backs over the mountains by way of the infamous Chilkook Pass. —Wikipedia

Some of them threw up jobs and farms to head north by ship then overland via the mouth of the Stikine River. Among those who chose this route were the three Vipond brothers, Joseph, James and Alex Vipond of Nanaimo, and Joseph Claus of Nanoose Bay. Their partners James Burns of Vancouver and Norwegian Charles Erickson likely were motivated by a sense of adventure as it was common knowledge that they carried as much as $1000 (a substantial sum in 1898) between them. The Viponds’ financial status isn’t known but poor Claus was just that—almost penniless.

So the stage was set. What began in Nanaimo with high hopes and dreams of striking it rich ended, tragically, only months later in the city’s courtroom and jail.

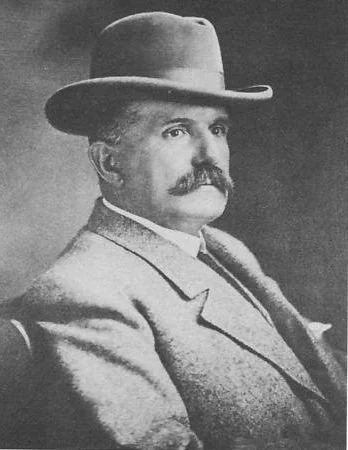

In Victoria, Superintendent of British Columbia Provincial Police Frederick Hussey received word of murder in the Stikine River country from Chief Constable Bullock-Webster. —BC Archives

Word of a grisly double slaying reached Fred Hussey, Superintendent of British Columbia Provincial Police in Victoria, from Chief Constable William H. Bullock-Webster. From Telegraph Creek, Bullock-Webster wrote on April 6, 1898: “I regret to have to report that a double murder has been committed twelve miles south of Glenora. The names of the murdered men are I believe Jess and Hendrickson. They were killed in bed by means of an axe with which their heads were cut open [and] they were then buried in the snow and rocks were placed on the top of them.

“This affair only came to my knowledge this morning and I am going to hold an Enquiry tomorrow [as] there is no Coroner.

“I am glad to say that three men who were partners with the murdered men and upon whom the gravest suspicion rests are camped here now, and I hope to be able to secure sufficient evidence to make arrests shortly.

“I can say nothing further at present but you may rest assured that I will do everything possible to bring the perpetrators of these murders to Justice.”

To fully understand how provincial police even hoped to administer law and order in such a remote wilderness 126 years ago, our best source is the late Cecil Clark who, upon retirement as deputy commissioner of the BC Police, began a second carer as writer and historian.

Here’s how he described the situation that faced the provincial force in the north in 1898:

“As chief constable, [Webster-Bullock’s] district headquarters were at Glenora, not far from Telegraph Creek on the Stikine River. There were 11 men in his command, holding down detachments at Lake Bennett, Teslin Lake, Echo cove, Fort Simpson and Port Essington at the mouth of the Skeena River.

“In all, he was responsible for an area far larger than his home country of England. Worse, the only access to Glenora was by sternwheel steamer during the brief summer months. After that, it was by dog team and snowshoes through miles of wilderness.”

But, as the record clearly shows, Chief Constable William Howard Bullock-Webster was the right man for the job. The son of an English army officer, he’d attended prestigious Sherborne School before emigrating to B.C. at the age of 20 in 1886 He join ed police force six years later and, upon the Klondike excitement in 1897,he was instructed to establish the police presence on the B.C.-Yukon border as described by Clark.

In due course–three weeks later–Hussey forwarded copies of his correspondence on the case to Deputy Attorney-General A.G. Smith.

By then he had further, although still not altogether accurate, information than that provided in Bullock-Webster’s original report. He knew that James Burns and Charlie Hendrickson were killed “at a point about twenty two miles below Telegraph Creek on the Stickine [Stikine] River,” and that three initial suspects had been narrowed down to James Campbell (actually Joseph Camille) Claus, one of the victims’ partners, who was suspected of having killed them to rob them of about $1000.

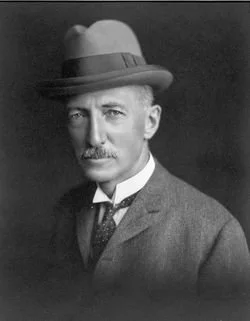

Long after his involvement in the Stikine River murders, NWMP Inspector P C H Primrose would go on to become lieutenant governor of Alberta. —www.findagrave.com

Hussey assured Smith that police had “what seems to be a good clue to start upon” and that he was confident that the case would be handled “in an intelligent manner by the local authorities,” meaning Bullock-Webster for the province and Inspector P.C.H. Primrose of the North West Mounted Police.

In echoing the outspoken sentiments of both officers in the field, he affirmed the “urgent necessity” for the appointment of at least three coroners for Cassiar District: one each at Glenora, Teslin Lake and Lake Bennett. He thought that the stipendiary magistrates already stationed at these locations were the obvious candidates.

In his letter of the 7th to Inspector Primrose, Bullock-Webster shows that there was still confusion as to the identities of all parties concerned. But his description of the wanted man is extraordinarily detailed, beginning with this dramatic sentence:

“I am camped on the scene of a double murder committed this week.

“The names of the murdered men are named James Burns and Charlie Hendricksen [sic]. They were killed with an axe and then put under the ice. They were in company with a man named James Campbel [sic] Claus from Nanoose Bay, near Nanaimo. The original party consisted of six, the other three being the brothers Vipond from Nanaimo, and Jess from Chilliwack. The party divided. I suspect Claus of the murder and I think he has gone to-wards Teslin Lake.

“This is his description: ‘Joseph Campbell Claus, a farmer, 5 ft. 6 ins. 150 lbs; complexion fair; small moustache; very light beard, bald forehead. Badly pockmarked; round faced; short neck; slightly hunched shoulders; peculiar walk, stepping stiffly - 35 to 38 years old; wore grey cowboy hat, dark brown strap with large buckle round hat rim of which is bound in leather.

“Also has a fur cap and woollen cap. Dark brown blanket lined canvas coat and pants. Light grey overshirt. Probably No. 6, ½ long shoes and hobnailed. Also has lumberman’s boots and leather sole rubber boots. Has .38 cal. S.&W. Revolver in scabbard. Yellow clothes bag marked,

Joseph Vipond and Co.

J.C.C.

“Black canvas sleeping bag sewed all the way up and has a piece of white duck canvas for a head overlap. Grey blankets. Wears open faced silver watch. Driving when last seen a buckskin cayuse and Mascott sled. Rope traces and spreaders and rope lines.

“Took $800.00 to $1000.00 in bills some of them $100.00 bills in two buckskin purses and one small leather purse. I am sending you this in the hope it may reach you; if it does kindly write particulars to Supt. Hussey, Victoria.”

Primrose did send it along, with the notation that he had given orders for “a strict watch to be kept in case this man breaks back this way but the River is in such a bad state I do not think he would attempt it at present.”

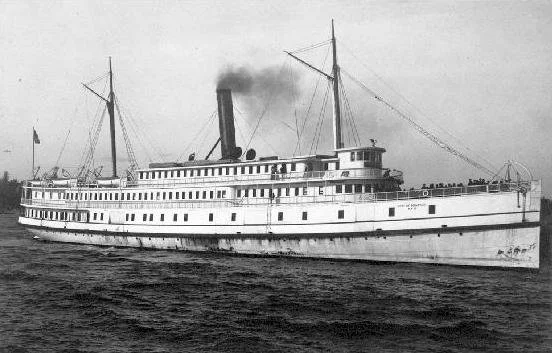

The American steamship City of Seattle brought the first public news of the search for a killer in the snowy north. —Richard Maynard Collection, BC Archives

Even with the case seemingly in hand, Hussey didn’t inform the press. Not until word of “a most cold-blooded murder” of “two trusting men” reached Vancouver by the steamship City of Seattle did Colonist headlines trumpet:

GOLD SEEKERS SLAIN: Two Canadian Prospectors Murdered in Cold Blood on the Stikine River Trail; Crime Attributed to Desire of Their Partner to Possess his Comrades’ Outfits; Alleged Murderer Reported Making Wild Ride From Scene of Tragedy.”

It’s intriguing to follow the somewhat torturous journalistic trail in that age before CNN, before global communications, when northern British Columbia and the Yukon were not only, at least in the figurative sense, the ends of the earth but, at the very least, a week distant when it came to sending or receiving news of breaking events.

This time-lag and the obvious difficulties of communication makes for a confusing chain of events, at least as they were translated by the two leading provincial newspapers of the day, Victoria’s Colonist and Vancouver’s News-Advertiser.

Both claimed their sources to be, literally, from the horses’ mouths. First to break the story, by a day, the Colonist claimed its informant S.A. Langstroth found the bodies. It was stated that the murdered men had been travelling, via Vancouver and Wrangell, with the Jess brothers and a man named Vipond but there had been a quarrel and the party split up, the Jess brothers and Vipond pushing on to Glenora, Hendrickson, Burns and “the Scandinavian” (Claus) following at a slower pace.

On April 5th, Langstroth, renowned as a crack rifle shot who’d represented his province at a national shooting match, was travelling with his own party. Twelve miles from Glenora, beside a small inlet, he stumbled upon two bodies in the snow. The skulls of both men clearly showed that they had been struck savage blows by a weapon, likely an axe, and it was assumed that they were asleep at the time as they were clad only in their underclothes.

Langstroth was overcome by the feeling that, frozen as they were, the bodies resembled wax images that he’d once seen in an American “chamber of horrors”.

An hour later, he spotted a man in a stooped position at a cache beside the trail. When Langsroth called out and hurried towards him, the stranger jumped atop his buckskin mount and galloped off. This same man, who answered the description of the missing Claus, was said to have been charging from camp to camp “like Tam O’Shanter with the furies after him”.

At one point he and his mount plunged through the ice. Rescued, he refused the offer of shelter for the night and continued his mad flight.

A coroner’s inquest had little difficulty in rendering a verdict of murder and fingering Claus as the likely culprit who, motivated by gain, had concealed the bodies in a rocky fissure between ice and shore. The slight possibility was acknowledged, however, that he, too, could have been murdered. But the description of the man on the buckskin matched both Claus and the cayuse used by the ill-fated prospecting party.

So, to quote the Colonist, to Joseph Claus went the alleged and dubious honour of having committed “the first cold-blooded premeditated murder...in the frozen north”.

(To be continued)