New Year’s Eve, 1895 - ‘A Coast Tragedy Without Parallel’

I really wanted to begin the new year with more of an upbeat story. But...

I also didn’t want to do another shipwreck so soon after the S.S. M.G. Zalinski, either. But...

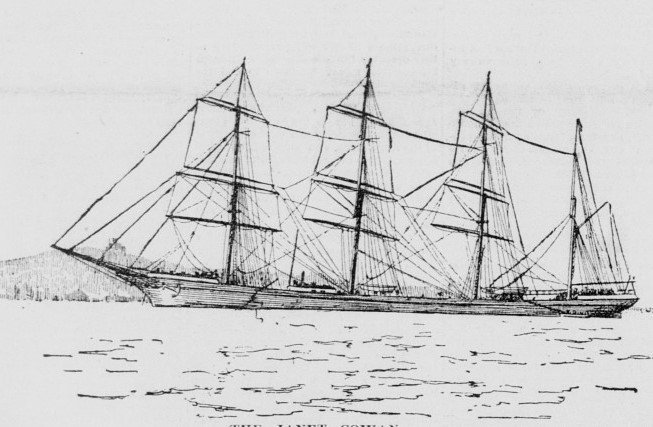

Ships of sail had little chance if they strayed off course along Vancouver Island’s western shore which was long known as the ‘Graveyard of the Pacific,’ and for “a wreck for every mile”. Among the many victims was the Janet Cowan, shown in a sketch that appeared in the San Francisco Call.

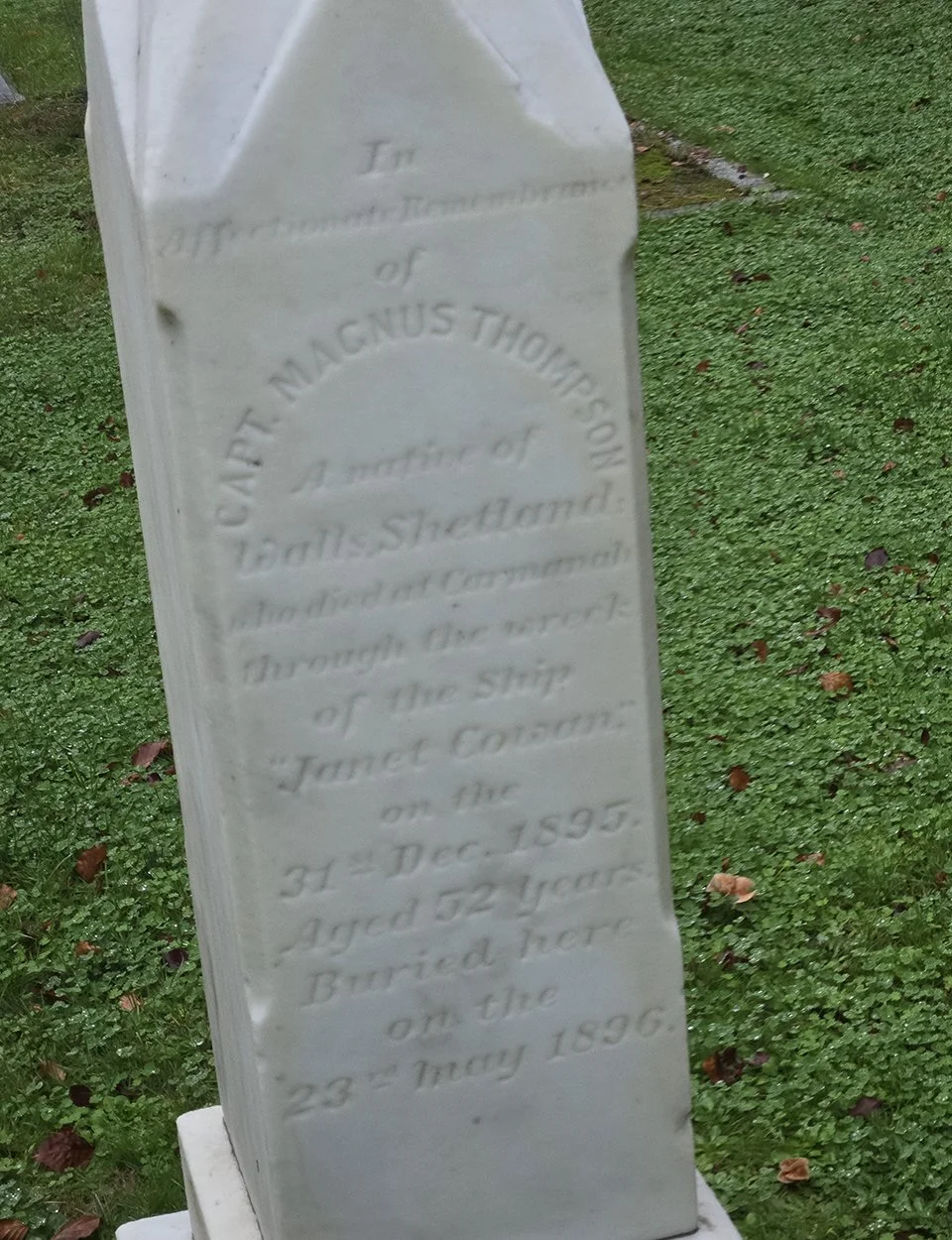

I was reminded of the poor Janet Cowan during a recent visit to Ross Bay Cemetery where I noticed Capt. Thompson’s headstone.

The story of the four-masted steel sailing ship Janet Cowan suits this time of year as she was wrecked with loss of a third of her crew at about the 19 kilometre mark of the West Coast Trail on New Year’s Day, 1895.

There’s a topical angle as well in that the Coast Guard, citing concerns over seismic stability, wants to shut down two of Vancouver Island’s most historic lighthouses, at Pachena and Carmanah points...

* * * * *

“A terrible tale of suffering... a coast tragedy without parallel,” cried the Victoria Colonist headlines, Jan. 14, 1896.

Shipwrecks were so frequent as to be almost commonplace off Vancouver Island’s treacherous western shore, 130 years ago. But the Janet Cowan’s ordeal is unequalled.

108 days out of Cape Town, she raised Cape Flattery light, December 29th. For 48 hours, Capt. Thompson vainly tried to stand off under a bitter sou’wester which steadily beat his lightly-laden, 2,497 ton ship into Barkley Sound. While seeking shelter in the driving blizzard, the Cowan ground into jagged rocks off Carmanah Point.

It was 2:00 a.m., Dec. 31st 1895.

Above the roar of wind, wave and buckling plates, the crew debated their chances. Janet Cowan was beginning to break up, just 80 yards from shore. It might have been 80 miles—no lifeboat could survive that frenzied surf.

“But there was a hero equal to the occasion, as there is in nearly all such calamities, and he stepped to the to the front,” reported the Victoria newspaper: Able Seaman J. Chamberlain offered to swim to shore with a lifeline.

“It's suicide!” shouted Capt. Thompson. As the young Englishman tore off his clothes, his frightened comrades erupted in cheers then fell silent. Their lives rested upon a slight youth’s courage—a boy against the Pacific Ocean. Surely he didn’t have a chance but, securing the line about his neck, Chamberlain paused, took a last look about his ship, then leaped into the sea.

Naked and alone, he vanished in the pounding surf. Minutes later, even the most optimistic had given him up for dead.

But Chamberlain was alive, barely. Although a strong swimmer, the threshing currents were pulling him under. Blue from the overpowering cold, bleeding from a hundred cuts after being ripped across razor-sharp reefs, he struggled on. Somehow, he kept his head above water as he gasped desperately for air. Although blinded by salt spray, he didn’t have to worry about direction as the breakers would sweep him ashore. If only he could keep his head up just a little longer...

Suddenly, his lashing feet struck something solid. Surging ahead with his last strength, he was drawn back then held fast. He was trapped.

Hours passed as those aboard the ship anxiously waited for a jerk on the line. But no signal came. Nothing could be seen in the raging blackness. Chamberlain was gone.

They couldn't know that his lifeline had become entangled on the bottom and that, too weak to free it, he must save himself. His wooden fingers tore frantically at the noose, finally slipped it off. Then, dragging himself forward, Chamberlain tortuously crawled into a hollow log for warmth. In the dark, he didn't realize he hadn't reached shore but a reef some distance away. A reef that would be awash at high.

The dramatic story of the end of the Janet Cowan, first reported in the Colonist, was carried in the Jan. 13, 1896 issue of the San Francisco Call. —UCR Centre for Bibliographical Studies and Research - California Digital Newspaper Collection

At last the wind began slacking enough to allow volunteers to launch a boat. Upon landing on Chamberlain's tiny ledge, they found the unconscious seaman and hustled him into dry clothing. He was paralyzed after his four-hour ordeal.

Securing a hawser to the ship, boatmen rigged up a breeches buoy (a canvas harness suspended from a rope) and soon all of Janet Cowan’s crew had reached the temporary safety of the ledge. But, again, they were prisoners. They still were a long way from the beach, a wild surf between. And the tide was coming in. Soon their island would be submerged.

Again, a hero answered the call. This anonymous saviour somehow made it to shore, where he set up the lifeline from a rocky bluff. One at a time, the 29 shipwrecked mariners rode the bosun’s chair to safety. But, midway, Capt. Thompson's benumbed fingers lost their grip, pitching him towards the sea. Miraculously, his feet hooked in the ropes and, dangling headlong over the rocks, he was hauled ashore.

Sheltering in the trees, they built a fire and nine men immediately began searching the area. Eventually stumbling upon the Carmanah Point – Cape Beale telegraph line, they followed it in the dark and, coming upon a small cabin a mile down the beach, moved in.

“The balance of the crew,” reported the Colonist, “passed the night as best they could, some of them getting their feet frostbitten. The fire...is all that kept them alive.

“Early the next morning, several of the men were sent to board the ship, which still remained in an upright position, and brought back canvas, provisions, ship’s valuables and, in fact, everything movable. While rummaging about the vessel for stores, First Mate Legall fell down a scuttle hole and broke his leg. He was taken ashore, lashed to the [bosun’s] chair, and carried to the camp in the woods.”

Tragedy continue to stalk them. That afternoon, having ransacked the ship, Second Mate John Howell and apprentices Walter Logan and William T. Steele headed back to shore. But their fragile boat capsized in the towering breakers. Days later, their bodies could be seen “being beaten against the rocks..."

On the second morning, Capt. Thompson divided his men into squads, having them scour the snowbound beach in opposite directions, confident that there was some form of settlement nearby as evidenced by the telegraph line and cabin.

There was only the Carmanah lighthouse, four miles to the west. But its keeper couldn’t see the Janet Cowan from his perch and the telegraph was no help as the same storm which wrecked their ship had broken the line in a dozen places. Their only hope was that a passing ship or fisherman would spot them.

The seamen glumly returned to camp. Other than the shack, they’d found not a sign of human life. The fever-wracked Thompson ordered them out again the next day. And the next, but to no avail. They were alone. By this time, too, Thompson and several hands were feeling the effects of exposure and exhaustion. Strangely, young Chamberlain had not only recovered from his daring swim but was one of the most active. Even when both feet froze, he continued to hobble about and nurse the others.

The men constructed a crude tent of sail canvas as a hospital for Capt. Thompson, Mate Legall, the cook and three seamen. But without medical supplies there was little Chamberlain and Steward Taylor could do for them.

On the 5th day of their stranding, Capt. Thompson died.

The loss of their master was a severe blow to the men. Thompson had kept them active and cheerful. With the first mate seriously injured, the second officer gone, the crew began to disintegrate. Nights were bitterly cold, the days empty. There was little to do, just one thing to talk about—survival. They could only wait. And pray.

On the sixth day, the cook and two others died. The engineer’s last hours were hell, he having to be forcibly restrained until death ended his torment.

The final misfortune—which convinced all that “the fates were against them”— came when the camp was deserted, all but Mate Legall and seaman Hunt vainly searching the empty beaches for help. In their makeshift hospital, Legall was lashed to a chair, Hunt rolled in a blanket on the earth floor. Both were helpless. Suddenly, Legall identified an order he’d noticed earlier—smoke.

“Hunt, the tent’s burning!”

Unable to stand, Legall yelled for rescue. There was no one to hear and Hunt could couldn’t move. Then Legall saw a rifle near the door. If he could just.. reach it... His fingers clawed empty space. Savagely rocking his chair from side to side, he inched toward the weapon, tipping his chair and spinning him onto his face in the dirt. But he had the gun.

Two shots brought the others running. The snow-shrouded canvas hadn’t burned easily although flames were reaching for Hunt when help arrived.

This incident drained the last ounce of hope and to a man, they sank into despondency. In complete silence, sprawled about the fire, they waited for death or rescue, they no longer cared which. Days passed, the men stirring only to keep the fire lit or to eat. Each morning, those in the in the line shack hiked to camp for food and implored their companions to return with them.

But Legall and Hunt couldn’t be moved and, even in their despair, the seaman wouldn’t consider abandoning their ailing comrades. They didn’t know help was coming.

En route to Alberni, Commodore John Irving had spotted Janet Cowan, still upright, sails set, from the bridge of the S.S. Princess Louise. Unable to put ashore in the running sea and gathering darkness, Irving proceeded to port and telegraph Victoria authorities. Returning the following day, he still couldn’t make a landing.

Thanks to John Irving aboard the passing S.S. Princess Louise, help was soon dispatched. —BC Archives

At the news, Capt.J. B Libby of the Puget Sound Tugboat Co., immediately dispatched the tugs Pioneer and Holyoke. It was a full three days after Irving’s sighting that a third company craft, Tyee, succeeded in landing men.

They were greeted by “a sight that will not be forgotten for years to come,” the Colonist noted. “Seated about a fire on pieces of wood and on the ground were 13 men, all wearing an expression of utter helplessness and misery. At the sight of Tyee’s men the scene was transformed into one of hope and hilarious joy. The castaways jumped to their feet and embraced their rescuers...”

Mate Hall of the Seattle tugboat described the wild experience:

Capt. Gove thought it best to make the attempt to land in the tug’s small boats, so I took several men, and Chief Hawkins took several, and we started. By good, hard pulling, we soon got alongside the ship and then passed under her bow. Once on the port side the weather was comparatively quiet and we had but little trouble in making a landing. There was a rope stretched from the ship’s side to the shore, so we knew that the crew was safe.

“After making a landing we climbed up a rope ladder that led to the top of a bluff which we could not see from the other side of the ship, and came upon the crew in a tent at the top. They were mighty glad to see us, I tell you. They wanted us to take them on board the tug right away. We assured them that they would be looked out for, and then started to look around for ourselves.

“They told us the terrible story of how they had suffered and what they had gone through through with, and it broke me all up. When they finished with the story we started into the woods to look for the bodies of the captain and the other men that had died from the cold and privations, intending to bury them, but we could not find them.

“Why, these poor chaps didn't have life enough to tell us where the place was.”

Days later, those from the cabin were in Victoria. It would be months before the bodies of Capt. Thompson and the others would be recovered and buried in Victoria’s Ross Bay Cemetery.

Capt. Magnus Thompson’s headstone in Ross Bay Cemetery. Of white stone, it stands out like a lighthouse amid its darker neighbours. —Author’s photo

Poor Janet Cowan was a victim of ignorance. Ignorance which cost seven lives and a 10-day nightmare for 22 others. Had Capt. Thompson not been a stranger to this deadly coast, he’d have crowded on sail and continued up Juan de Strait rather than retreating towards the open sea. Once stranded, the crew should have remained aboard—a fact they couldn't foretell as it seemed that the Cowan must break up beneath them.