No Mercy for Camp 6 Sweetheart

Part 1

Caycuse, aka Camp 6, in 1933, five years after the Mable Jones tragedy. —Courtesy Tom Teer

It’s funny how some things turn out. Funny, that is, if such a term can be applied to human tragedy—particularly to that of a sensitive young woman who was driven to taking her own life by a confined, uncaring, even malevolent community.

Such, however, is the story of Mable Estelle Jones. Almost a century after her death, her story serves as the subject of a teacher’s course in ‘historical studies’ and as a lesson in human behaviour.

Too bad that we never seem to learn from history…

* * * * *

It was back in 1902 that George Lewis logged in the Harris Creek area, using one of the earliest steam donkeys in the region. He was followed three years later by Joe Vipond who contracted for the Mossom Boyd interests’ Cowichan Lumber Co. About 1909, Empire Logging became active here, followed by the Genoa Bay Lumber Co. and the legendary Jesse James.

In 1927, Chris Gilson’s and Wade McCoy’s Cowichan Lake Logging Co., with contracts to cut timber on the Empire Company’s vast holdings for the Youbou mill, established a permanent logging communities at the mouth of Nixon Creek.

They recycled old float homes from the Medina Mill townsite across the lake at the mouth of Cottonwood Creek. Their Camp 6, with its mix of houses and company buildings on floats and on shore, became known as Caycuse, a somewhat curious choice of native terminology that means scraping the barnacles off the bottom of a canoe—despite the fact that Cowichan Lake is fresh water and, need it be said, barnacle-free.

A Camp 6 crew moves an Industrial Timber Mills Co. cold-deck machine at Caycuse in 1936. —Author’s Collection

Over the years the settlement grew to 100s of residents. Even when the last of the raft-homes were moved onto terra firma in the late 1940s, the Camp remained accessible only by boat and by logging railway.

This made for a close-knit, insular community with a “quite varied…social mosaic,” as historian Ian Baird described it in the Victoria Colonist in 1983. While “Chinese comprised the track gangs [and] Finns and Swedes accounted for the majority of the logging crews,” ethnocentrism doesn’t seem to have played a significant role, Baird noting that social acceptability in Caycuse was more likely to be measured in terms of merit rather than one’s national or racial background.

Which should have meant that a young schoolteacher who was of respectable Anglo Saxon origin and eager to prove herself, would fit in easily.

Mable Jones’s photo in the Victoria Normal School yearbook. —Times Colonist

Such, however, wasn’t the case despite the rosy picture later painted by Camp Manager Christopher Gilson. He claimed to have taken a fatherly interest in the young woman whom he’d personally hired. She was “such a sweet and lovable [sic] girl that no-one could have known her and not worshipped her… We did everything in our power to make her feel that she belonged to us, that she was part of our life. She was the camp sweetheart.”

But there was a dark undercurrent to Gilson’s wistful recollection of Mable Jones’ 15-month-long presence in Camp 6.

What Gilson hadn’t mentioned was that she was attractive and unmarried, highly desirable pluses for the single loggers, no doubt, but equally disconcerting minuses for some of the camp’s married folk. What made life so difficult for Mable was her naivete. It would appear that a cloistered upbringing with loving parents and a brother had failed to arm her against the constant scrutiny and the slings and arrows of life in a small, enclosed community.

An older, mature woman might well have endured the almost inevitable gossip and criticism that, over months, became more than Mabel Jones could bear.

None of this could have been foreseen when the pretty and petite 18-year-old English immigrant left her parents’ home in the up-Island coal village of Cumberland to enrol at Victoria Normal School in 1926. Mable was one of 1000s of young men and women who attended VNS over several decades to achieve their teaching certificates as part of an established provincial policy to staff schools.

Many of these were only one-roomers, often extremely crude affairs in isolated rural communities (some of them of brief existence), and spread out over a province of 950,000 square kilometres (more than 1.5 million square miles)—effectively, an area almost twice the size of France.

Upon graduation with as little as eight months’ theoretical training, these novice teachers, many of whom were women (and necessarily single) from urban settings, were literally parachuted into tiny backwoods societies where they knew no one, and where they often had to board with one of the school trustees. This meant a loss of privacy and freedom in their out-of-class hours and the inevitable and inescapable 24/7 personal scrutiny by the very people who employed them.

Not to mention the stern overview of school inspectors during their periodic visits.

Teachers committed to a one-year contract. For many of them, it was a long year indeed and it soon became the pattern for new teachers to serve just a single term in the outback then seek more urban postings where they had more control over their own private lives, or to find work within the educational system but outside the classroom.

The keys to a teacher’s early success were the trustees, many of whom had children attending the school that they were overseeing. A provincial-wide system that was operated virtually by remote control from distant Victoria had to rely upon local trustees to manage the affairs of the community school with competence and in good faith.

These children in an unidentified frontier classroom are smiling for the camera; but this wasn’t always the case while they were learning the 3Rs from young and inexperienced teachers. —www.oneroomschoolhouses.ca/the-schools

As B.C. schools historian Thomas Fleming wrote in his 2011 book, Worlds Apart, a study of the politics and labour relations in the province’s schools before and after 1972, the Education Office expected trustees and local communities to provide educational facilities, govern local schools, hire and pay teachers, and supply the school’s heating, water and janitorial needs.

More importantly, it counted on the trustees providing “vital wisdom and information about local conditions [and] to find housing for young and inexperienced teachers”.

Tragically for Mable Jones, she won general acceptance in Caycuse, the tiny logging community to which she was assigned, and even enjoyed the paternal friendship of the company manager, but she antagonized the key players in her cossetted world, the school trustees.

Shy and not given to general socializing, Mable was remembered by the closest of her fellow students as having been fun to be around, active and mischievous with “a merry heart”. Upon graduating as an elementary school teacher with a second-class certificate, Mable was hired for $900 per annum to begin teaching in Caycuse’s one-room school in September 1927.

Her mixed class consisted of nine girls and seven boys, six of whom were in Grade 1, four in Grade 2, one in Grade 3, two each in Grades 4 and 5, and one in Grade 6. These included the children of two of the school trustees, Secretary and Treasurer M. Robert Magnone and Mrs. Malvina Peck, the third trustee being William Miller.

Although it was her first year as a teacher, in a new and more confined environment than she’d known even in small-town Cumberland, Mabel received a passing grade from Public Schools Inspector Stewart who thought that her pupils were making adequate progress and that her schoolwork and discipline were satisfactory.

Her recent training as a teacher showed itself in her modernistic approach. As was the style of the new and more enlightened 1920s, Mabel favoured the writing of lines instead of corporal punishment, and she had her students clip stories and photographs from magazines for pasting in their notebooks. As modest as these may sound today, they were almost revolutionary in the 3Rs and ‘spare the rod and spoil the child’ age of a century ago.

Perhaps the last surviving Little Red Schoolhouse at 150 Mile in B.C.’s Cariboo District. We can bet that Mable’s rustic classroom at Caycuse didn’t look anything like this. —Canada’s Historic Places

For that matter Caycuse was, for a time at least, good for Mabel, too.

She got to teach in a new schoolhouse built to government standard and, for $30 a month, she enjoyed the relative luxury of her own furnished quarters. With kitchen, bedroom and sitting room “fixed up in a way that [we] thought she would appreciate,” the whole idea, said Manager Gilson, was to make life “a little nicer for a girl away from home on her first job”.

Mable even had a boyfriend. Among the young men who swarmed about the pretty schoolteacher was ‘Pete’ O’Neill, a railway brakeman whose attentions soon progressed to courtship and a proposal of marriage. With her parents’ blessing Mable agreed to a date in June 1929, at the end of the second school term.

But not even their engagement was enough, it seems, to put an end to the whispering that, although ostensibly directed at her work in the classroom, likely was sparked by jealousy and the wishful suspicions of personal impropriety. This, despite Pete’s attempt to protect her from “talk” of immoral behaviour by not setting foot inside her cabin unless a third person was present.

As if this weren’t enough of a load to carry on her inexperienced shoulders, Mable had other pressing worries. Her mother was ill. She wanted to supplement her coal miner father’s income but her salary was insufficient. Her anxiety began to show.

Miners’ cottages in Cumberland, 1889; living accommodations for these coal miners hadn’t improved all that much by 1928 when Mable supplemented her father’s pay cheque from her salary as a teacher. —BC Archives

When some parents voiced their disapproval of her teaching style, she went to Manager Gilson for consolation. He attempted to allay her concerns by reminding her that the school inspector had approved her work* and assured her that he’d always be there for her should she need him. She promised him that she’d go to him if she felt it necessary as she looked upon him as a second father.

Too, she had Pete’s shoulder to cry and to lean on. He was as supportive as he could be under the circumstances, cutting her firewood and delivering her mail and all the while encouraging her to hang in.

It was while he was working on her woodpile after work, Monday the 13th, that senior trustee Magnone dropped by. As Pete deferentially stepped to one side, he heard Magnone say, as he handed Mable a note and the school flag that his wife had mended, “Here are a few complaints I wish you to attend to.”

Magnone waited while Mable read the note in the house. She quickly returned and, crying, responded to the criticisms he’d itemized:

The first charge dealt with her apparent habit of letting the flag fly rather than raising and lowering it daily. Mable explained to Magnone that she’d repeatedly asked the Camp carpenter to fix the rope as it frequently became entangled. Magnone, acknowledging that he’d had trouble with the flag himself, suggested that perhaps she should let some of the older boys in her class attend to that duty.

As for the “careless manner in which the children are allowed to march into school” that could be interpreted as a lack of discipline, she explained that she often restrained the children’s natural exuberance by having them march into class two or three times.

Her having students “waste scribblers” by using them as scrapbooks for “cut-outs” was something she’d been taught to do in Normal School. Magnone, in a tone of voice that Pete described as not being harsh, replied that her students had consumed more scribblers in a single year that he’d used in all of his schooling.

She continued to be upset after Magnone left. Pete asked her if she wasn’t taking the matter too seriously. She replied that she couldn’t help it; the thought that some parents were criticizing her before their children made facing her students unbearable. She thought she should resign.

Hoping to cheer her up, he talked her into attending a house party. But Mable’s mood didn’t improve through the evening and they had but a single dance. Even Manager Gilson noticed that she was withdrawn and that she appeared to be worried or depressed.

Victoria’s imposing Normal School, known today as the Lansdowne Building, where 1000s of young men and women trained to be teachers in the B.C. Public Schools system. Mable Jones’s tragedy alerted the government and the public that months of academic training were insufficient to meet the difficulties of inexperienced teachers having to work with equally inexperienced school trustees. —

httpscurric.library.uvic.ca/homeroom/content/schools/public/vicnorm.htm

They left “early,” about 1 o’clock, at her request. Back at her cabin, although it was mid-November and cold and damp, they sat on the steps until 2:15, discussing among other things Pete’s suggestion that they move up their marriage date by six months, to Christmas. He’d testify at the coroner’s inquest that Mable demurred because she continued to fret over her mother’s health and her own inability to help more with her parents’ finances, let alone deal with the expenses of a wedding and setting up house.

By the time Pete left, they’d also discussed her seeking another job. She would feel better in the morning after some sleep, he thought.

But with Tuesday morning, the children arrived at an empty schoolhouse. When, by 9 o’clock Mable still hadn’t appeared, a neighbour called at her cabin. Noticing that there was no smoke issuing from the chimney, and expecting to find that she wasn’t feeling well, Mrs. Jane Clark Davy was little prepared for the grisly scene that awaited her knock.

She found the teacher’s body on the floor, on her back with arms and legs outstretched, already cold in death, a .22 calibre rifle at her side and a note pinned to her dress. She was fully dressed and still wearing her coat.

Upon being informed, Gilson had the cabin locked up and sent word to the nearest provincial police detachment at Lake Cowichan. As it happened, the telephone line was down and word had to be relayed by boat and phone via the McDonald-Murphy logging camp at Rounds.

Constable Alex. Dunbar, finding her house in order, the bed made, observed a box of opened stationery on the table, two cases of .22 ‘short’ cartridges, a short piece of lead pencil and a crumpled handkerchief. A note, folded over several times, was pinned to her breast. Not written on the same paper as the stationery pad on the table, it was addressed to Mr. Gilson.

A second note, addressed to Pete, came from the notepad. Dunbar took several photographs, observed what he took to be a head wound and face cream on the muzzle of the rifle, then had the body removed to a Duncan mortuary.

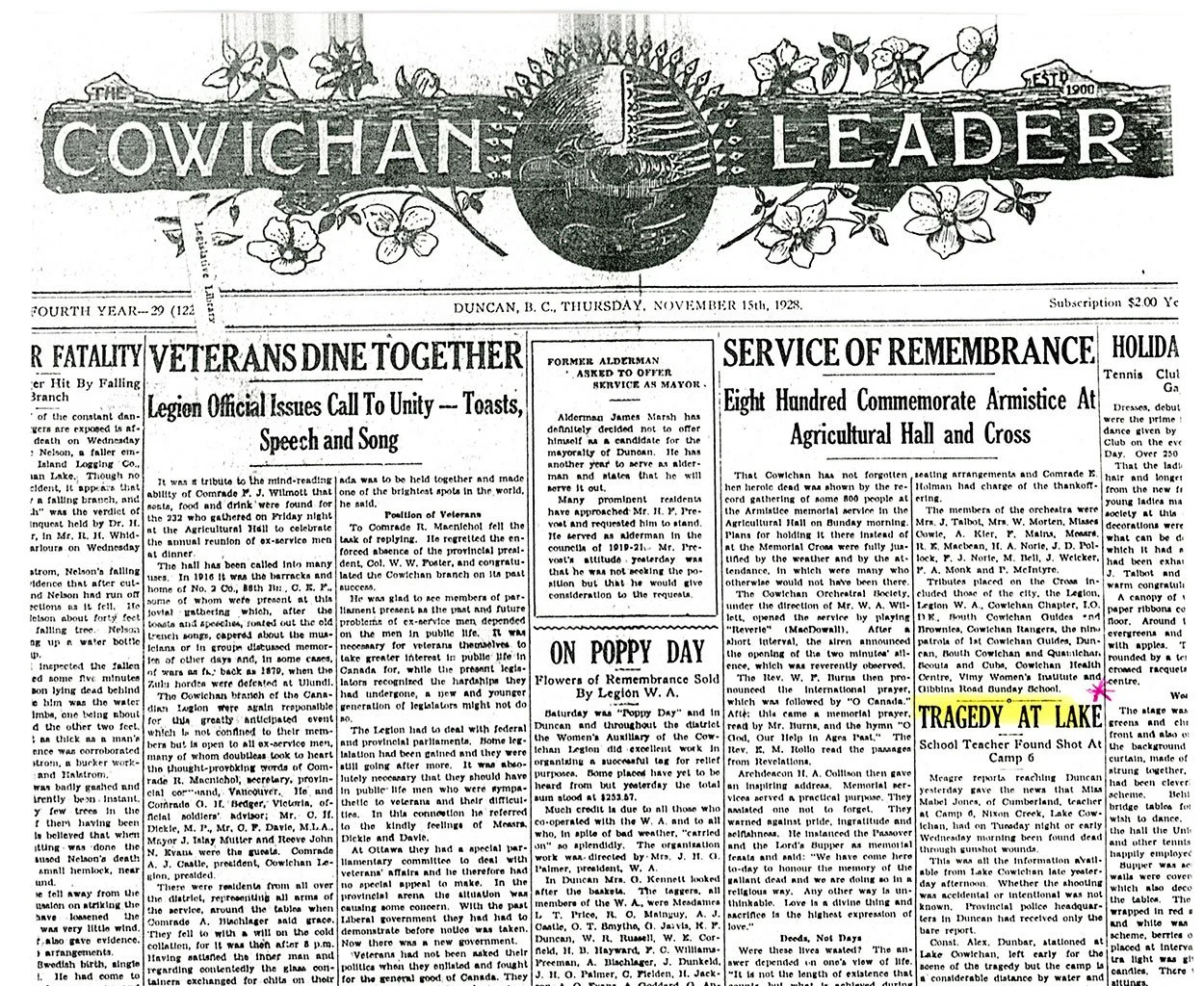

The shocking news caught Cowichan’s twice-weekly newspaper, the Cowichan Leader, going to press.

With little to go on and little time in which to investigate, the November 15th issue of the paper settled for a small, cryptic report on its mid-front page. Under the headline, “Tragedy at Lake,” it merely stated that Mabel [sic] Jones of Cumberland, a teacher at Camp 6, Nixon Creek, had been “found dead through gunshot wounds…whether accidental or intentional was not known”.

Mable Jones’s story didn’t end with her death by suicide. When the circumstances of her last months at Caycuse became known, there was a public outcry to change a system whereby unworldly young people had to face up to not just their own inexperience and frailties, but those of equally disadvantaged—or malevolent—school trustees.

(To be continued)