‘On-To-Ottawa Trek, 1935 (Conclusion)

—www.labourheritagecentre.ca

This week we conclude our comparison of the ‘On-To-Ottawa Trek’ by thousands of unemployed men in 1935 to the recent three-week-long occupation of Ottawa and the blockading of crucial border crossings by truckers and supporters virulently opposed to continuing government health mandate.

Again, this week’s Chronicle is based upon the condensed “recollections” of onetime Lake Cowichan resident and Spanish Civil War veteran Ronald Liversedge.

His memory isn’t infallible. By the 1960s he didn’t remember every name, he sometimes struggled with the actual sequence of events when so much happened about the same time, and his crowd estimates are perhaps high. That said, his insider’s view, partisan though it is, is historically priceless.

(A summarized and generally accepted views of these events by historians appears in Editorially Speaking...)

As we saw last week, thousands of Relief Camp Workers, as these unemployed single men in B.C called themselves, had rebelled against federally-run relief work camps where they’d laboured for their board and 20 (not 25 cents as I said earlier) cents a day.

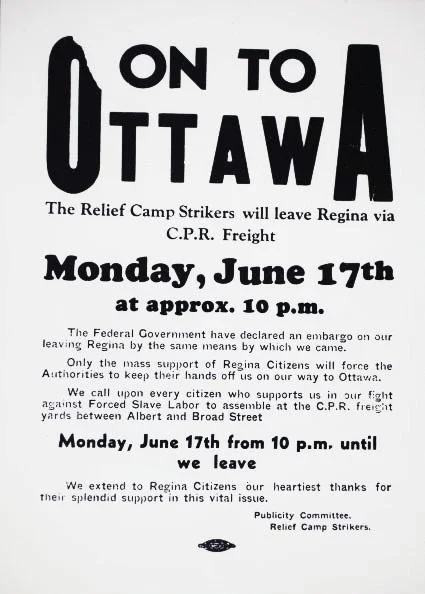

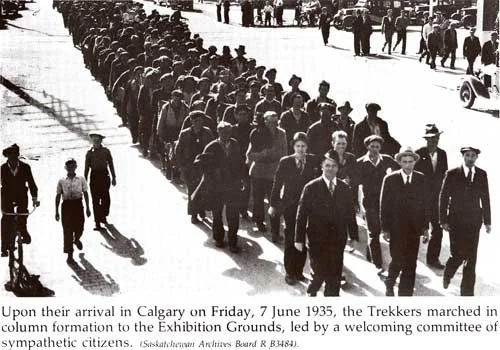

Several thousand converged on Vancouver to seek relief from the City while they continued to press for direct negotiations with the Conservative government of R.B. Bennett. In June 1935, after months of public demonstrations, occupation of the Vancouver Public Library and skirmishes with city and provincial police, they resolved to take their case to Ottawa by ‘riding the rails’ across Canada.

—www.labourheritagecentre.ca

Reinforced by 500 Alberta unemployed they made it to Regina where they received an offer to send a delegation to meet with the prime minister.

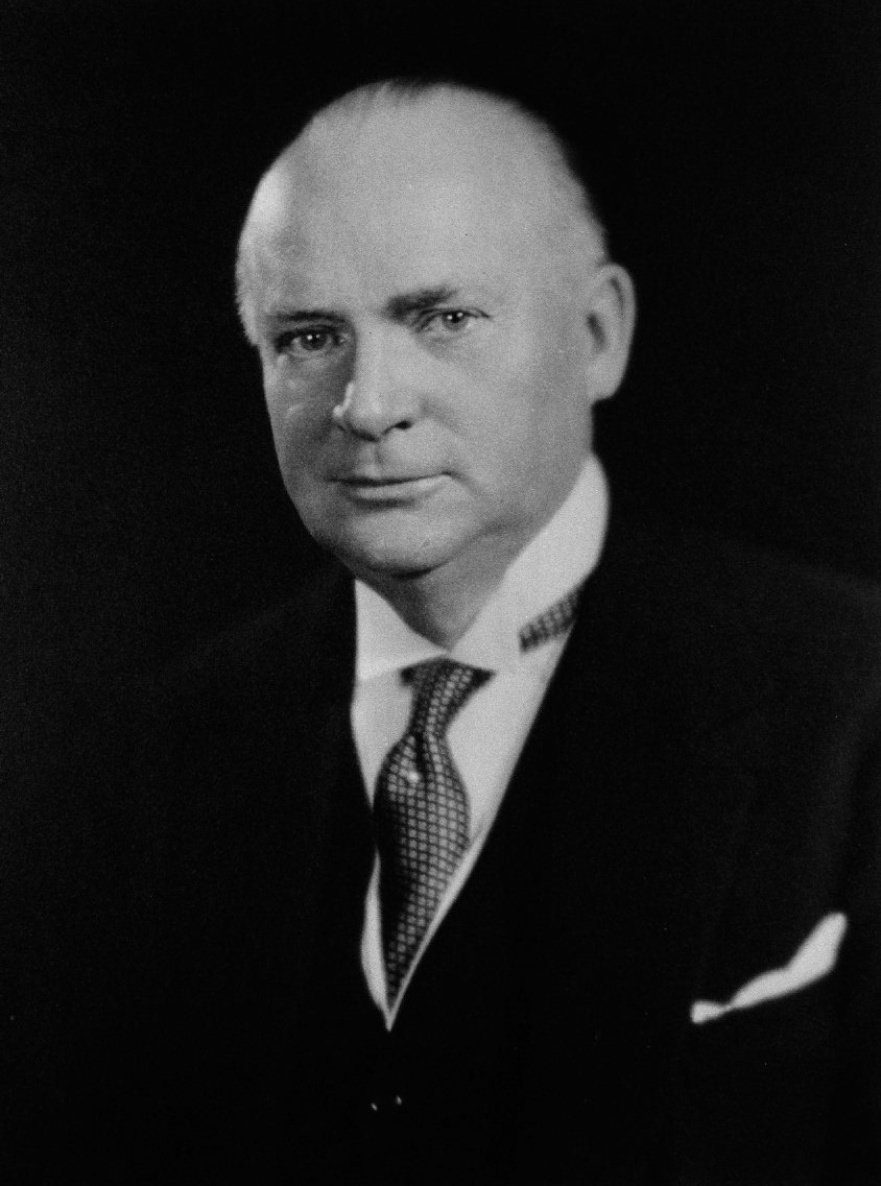

Ronald Liversedge: “Even school children realized that the Prime Minister was incapable of making the proper gesture [by] offering to redress our wrongs. Every Canadian worker knew that in any dealings with the ordinary people of Canada, Mr. Bennett’s mind was incapable of rising above the double-cross.

“The federal government, which was in fact R.B. Bennett, needed time to gather police reinforcements at Regina, hence the belated offer to negotiate with the camp workers... Despite all these considerations we had to accept the offer of negotiations.”

Many of the men were determined to continue the Trek; only after three hours of heated discussion was it resolved to dispatch a delegation to Ottawa. Here, Liversedge resumes his tale:

* * * * *

From that day on the Trek took on a different complexion and a different tone. The men drew closer together, there was a new awareness, a new alertness. All seemed to be aware of and preparing for some kind of a crisis.

Before the delegates left for Ottawa, a small committee from our Central Strike Committee contacted the Saskatchewan premier, Mr. James Gardiner, his attorney-general, Mr. Davies and some members of the cabinet. We apologized for our continual presence in Regina but assured the premier and his colleagues that...we could guarantee the good behaviour of every single man on the Trek.

This was the first of a series of meetings between the Saskatchewan cabinet and our committee. The meetings were always cordial, and Premier Gardiner and Mr. Davies were always courteous and friendly whenever we met them.

The delegation of eight from the Trek had left by train for Ottawa. [Arthur ‘Slim’] Evans was the leader and main spokesman... We tightened up our regulations as we were receiving authentic news of police reinforcements arriving steadily and being stationed around Regina. Militia being warned to be ready for call. Ominous signs. We were having routine marches around town, but one Division was always left at the Exhibition Grounds on guard.

The boys played baseball and other sports. Everyone was getting more than enough to eat (until the delegates met with the prime minister the government guaranteed the men three meals daily)...

Then came the news of our negotiations. All of Canada was agog with the news that night. Our delegation, after a night’s rest in an Ottawa hotel, had been summoned to the Cabinet Chamber for the meeting with the Prime Minister.

There sat Bennett behind his desk, surrounded by officials and guards. There were the press and in front of Bennett the right representatives of the Trek.

The Prime Minister wasted no time but went into his diatribe of abuse, condemnation and threats, his face crimson with hatred.

He then singled out Slim Evans and roared, “We know you down here, Evans! Your a criminal and a thief!” At this, Slim calmly rose to his feet and, looking the Prime Minister in the eye, he said, loudly and distinctly, “And you’re a liar, Bennett, and what is more you are not fit to run a Hottentot village let alone a great country like Canada.”

The delegation was hustled out and that was our negotiations.

The offer of negotiations, openly and cynically a trap, the getting of the delegation to Ottawa, the heaping of verbal abuse on their heads, with no intention of negotiating, all this, even coming from Bennett, was, in the eyes of the Canadian people, shameful and inexcusable.

In Regina we awaited the return of our delegation and upon its arrival a public meeting was held to report. It was a big meeting, and a condemnation of the boorish conduct of the Prime Minister. It was felt by the majority of the Trekkers that we would have to retreat. The leaders of the Trek were in daily contact with the Saskatchewan cabinet and beginning to arrive at an agreement for calling off the Trek.

Evans constantly warned Premier Gardiner and his ministers of the danger of allowing the federal authorities to usurp provincial autonomy in the field of law enforcement. The Cabinet in Regina were fully alive to the danger and all, from Premier Gardiner down, knew that the Trek posed no threat to law and order in Saskatchewan. They accepted our pledged word as sacred.

We knew that with the hundreds of police reinforcements we could not continue east on the railroad without severe strife and bloodshed.

Then came the federal order-in-council, directed to the people of Regina, stating that any person who from that date who gave aid or succour to the “On To Ottawa” Trekkers would be prosecuted under Section 98 Of the Criminal Code.

By the first of July 1935, our plans were made to call off the Trek.

Most of that day our Committee had been conferring with the premier and cabinet, and a public meeting was scheduled for the evening on Regina Market Square to acquaint the public of our decision. All that was left to do was the working out of the details of our retirement. The Saskatchewan government had promised their help but the federal government had other plans.

Dominion Day, 1935, our country’s birthday, and what a birthday celebration it turned out to be.

The meeting that evening on Market Square, while not being as big as most meetings we had held, still had a substantial audience, probably 1500 men and women, townspeople, some with their children. It hadn’t been thought necessary for a full turnout of Trekkers as the meeting was to inform the people of Regina what we, the trekkers, already knew.

There were probably 4-500 of us on the Market Square and there would be 2-300 still having supper or walking around town. The vast bulk of our men were watching two ball games out at the Exhibition Grounds.

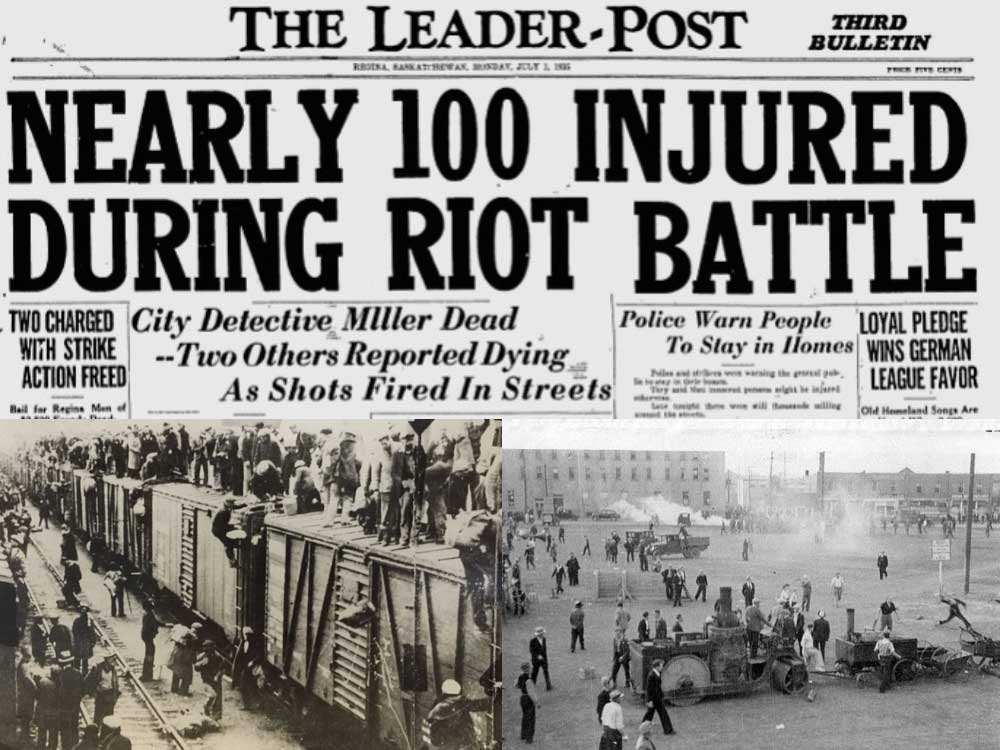

The meeting wasn’t long underway. Evans was speaking when four large furniture vans backed up, one to each corner of the Market Square. A shrill whistle blasted out a signal, the backs of the vans were lowered and out poured the Mounties, each armed with a baseball bat.

They must have been packed very tightly in those vans, there were lots of them. In their first mad, shouting, club-swinging charge they killed Regina City Detective Miller [sic] who evidently had come onto the Square to help them. In less than minutes the Market Square was a mass of writhing, groaning forms, like a battlefield.

—www.labourheritagecentre.ca

As we retreated I saw one woman standing over an upturned baby carriage which had been trampled by these young Mounties, and I saw four Mounties pulling at the arms and legs of one of our men whom they had on the ground while a fifth Mountie continued to beat viciously at the man’s head. This man they had down spent the next year in the mental institution at Prince Albert.

The surprise was complete and a victory for the Mounties, the only one they had that night. Even at that, they were unable to follow up as there were also not a few Mounties writhing on the ground, and it took about half of their number to arrest Evans and the few boys on the platform.

The word went around quickly, for Trekkers to assemble on one of the main streets to march back to the Stadium. Here is where our long stress on organization and discipline paid off.

A number of men were dispatched to thumb a ride out to the Stadium to warn the Trekkers not to come downtown, but to post strong guards at all entrances. [In town] we assembled under Group leaders. Hilton and Paddy O’Neil took the head of the column and we had just started our march when somebody in a car coming towards us told us that there were 200 horsemen lined across the street ahead of us, and then unmistakably from away behind came the clop-clop of a large body of horsemen.

It was to be a squeeze-play.

We were not going to be allowed to get out of town. We were to be smashed up. How incredibly stupid. Immediately, orders were given us to build barricades, and there was plenty of material to work with.

The street was lined with parked cars and we simply pushed them into the streets, turned them on their sides, and piled them two-high. The barricades were built quickly, solidly across the street, from wall to wall, with one narrow opening, wide enough for one man at a time to pass through, and we built quite a few, a couple of hundred feet apart.

It was then, before the first futile charge was made by the Mounties, that the miracle happened.

The young boys, and even some girls, of Regina organized our ammunition column. Without being asked, they came riding bicycles in from the side streets, their carrier baskets loaded with rocks which they dumped behind the barricades, and then rode off for another load.

The Mounties never reached the first barricade, that is, the ones at each end of the street, and the attempts which they made to get behind and between the barricades from the side streets were all beaten back. Our defence was simple; in front of the barricades, two lines of us formed, one behind the other, right across the street, each with a good armful of big rocks.

There were casualties in every charge; the horses couldn’t face the rock barrages and always turned down the side street in front of us, often with the rider laying on the horse’s neck.

Besides this main battle there were skirmishes going on all over downtown. Some groups had left the Exhibition Grounds for town before the general order to stay there had been given, and these men were trying to join us on the main street. Some of the men from the Market Square who had fought the rear guard action from the Square were trying to join us from another direction and meeting roving squads of Mounties on foot.

The police must have had orders to beat and rout us thoroughly that night for there can be no other explanation for the senseless continuation of their stupid horse charges.

We were not a rabble. We refused to be beaten up. We had tried desperately to avoid combat, even after the first unprovoked police attack. Whatever order was brought out of the chaos that night, then it was us, not the police, who brought about the order.

At one intersection where some of our men with lots of rocks were keeping at bay a squad of Mounties on foot, the Mounties tried tear gas, but they fired them into the wind and the boys picked the gas shells up and threw them back to the Mounties.

It was here that the police fired the first revolver fire, the first casualty being an innocent bystander or passerby. He was a hospital orderly on his way to work at the general hospital when he got shot through the stomach and was still in a serious condition some months later, the last I heard of him.

It was a terrible night, downtown Regina a shambles. Not a store with a window left in, the streets piled up with rocks and broken glass, dozens of cars piled up in the streets with no glass in them, and twisted fenders and bodies.

Around 10 o’clock that night the police started to withdraw from the streets. They were exhausted and demoralized. At first we were cautious then Hilton in a commandeered car cruised around a few blocks and came back to report the streets clear.

It was decided that we break up into groups, scatter and make for the suburbs, and by circling round the city, get back to our headquarters at the Exhibition Grounds, as there was no possible chance to get there by the main route which was heavily guarded by cordons of police.

This plan was carried out and most of the men got back. The people in the suburbs who were all out in their yards were very helpful, pointing out the best routes to take, and warning of which streets were being patrolled.

The group with which I started out had one more fight to face before we got them out of town. Circling round we came to an intersection [which was] crowded by a large body of our men. On one corner of the intersection was a movie house, the lobby of which was crowded with Regina people... Almost a block away, and facing our men, were two lines of ordinary City Police in blue uniforms and helmets, shoes brightly polished, and very fresh looking.

It transpired that they had all been flown in from nearby towns. There were about 100 of them in two lines right across the street, and they were evidently being readied for an attack as they stood with batons drawn. Behind them were two lines of the Mounties, on horses. All was very quiet as we arrived but there was plenty of evidence that heavy fighting had taken place.

Like the rest of downtown Regina the street here was ankle-deep in rocks, our men breathing hard but standing relaxed although each had an armful of rocks. The Mounties on their horses looked droopy and dejected. Only the City Police looked fresh. The boys told us that the blue coats had just arrived, something new was going to be tried.

All at once they started to come and our Group Leaders gave the order, “Line up, boys, here they come!”

We took our positions cross the street. Three lines of us, heavily armed with rocks. The blue coats marched towards us as on parade, stately and unhurried, towards us. It was a psychological attack but nobody’s nerve broke.

As the cops drew quite near, nobody running and no missiles coming yet, they showed some uneasiness.

Then came the command from our leader, “Now, boys, and make it quick!”

The blue coats tried to keep coming but as one and then another went down they broke, and our first rank went after them. To escape our attack the retreating bobbies drew their revolvers and opened fire. It was the heaviest gunfire of the night and half a dozen of our boys were wounded. [40 Trekkers received gunshot wounds—TW.]

Then came the Mounties [but they were] beaten back. The men of the Trek were in a dangerous and resentful mood, bitter, and fighting mad. The mood seemed to be, “You, the police, started this madness, you won’t let us withdraw, so, all right, come and get it.”

As it turned out, that unsuccessful attack by City and Mounted Police was the last big skirmish of the night.

After the police withdrew down the block, taking [their wounded] with them, and we had our own wounded started towards hospital, there came towards us, a military figure. As he drew closer we saw that [he] was a City Police inspector or captain. He had the gold braided peak cap and the black braided uniform. He came right up to us and said, “Are you men going to disperse?”

One of our leaders answered, “Where have you been all night? And what the hell do you think we’ve been trying to do all night?”

“Never mind that now,” this man said. “I’m in charge here at the present time and this nonsense has gone on long enough. I’m giving you a chance to get out. From now on it’s going to be all bullets. I’m going to clear the streets and I’ll clear them with gunfire if it’s necessary, but I’m giving you time to clear out of town.”

And turning to the Regina folk who were crowding the foyer of the cinema, he said, “And you people can go home if you do it right away, or otherwise go back into the theatre and stay there until you’re told to go home.’

We, on our part, said, “That’s all we’ve waiting to hear all night, and good night to you, Captain.”

We split up and started out, some of the men fearful of the consequences of the night, and not trusting the promises of anybody in office, made for the open prairie, but the majority made it back to the Stadium. For all of us it was a sad journey...

Our group arrived at the Exhibition Grounds at 2 o’clock in the morning and lay down in the straw to sleep for we were so exhausted, so drained out, so stiff and sore, that it was a day or two before we could relax sufficiently to sleep.

It had been some day and some night, and I was bewildered trying to weigh up the score. About [100]of our members were in jail, including Evans and some of comrades suffering from gunshot wounds. One man killed, scores of other casualties, of whom I think the Mounties would claim the majority, and material damage in the heart of Regina amounting to 100s of thousands of dollars.

What a price to pay for the defeat of a government and the extinction of a political party, for although Richard Bedford Bennett was too great an egotist to admit the fact, he had, on that Dominion Day in 1935, signed the death warrant of his government and party for the next two and a quarter decades.

—www.labourheritagecentre.ca

July 2nd, 1935, we arose from our straw to the gabble-gabble of excited comment, and on emerging into the open, a truly marvellous, almost unbelievable sight met our gaze.

The Exhibition Grounds at Regina were fenced in by that strong, industrial fence, with entrances at intervals all around the Grounds, and at every entrance was a squad of Mounties with mounted Vickers machine guns facing into the Grounds.

As [this] story is absolutely factual, I can say that the majority of our members were not unduly concerned about the situation. [Our] problem, though, was to restrain our young and impetuous members from provoking the RCMP. At every machine gun post our young fellows would stroll up and taunt the Mounties. “How did you like last night?” “Now you have the advantage, why don’t you open up with your toys?” or “Are you still as yellow as you were last night, you bastards?”

We had to put on our own police force to restrain our men. Into this situation stepped [Premier Gardiner and Attorney-General Davies who] met with our Strike Committee. In all our dealings with them we found [them to be] very good scouts. Their given word and ours were respected and adhered to.

Whatever communication went on between the Province of Saskatchewan and the federal government, I don’t know, but within three days the Mounties and the Vickers were withdrawn and we were negotiating the final act in our Saskatchewan drama.

The conditions of settlement were that any man on the Trek could proceed to his home or wherever he wanted to go, with the transportation provided, and that the originals from B.C. would be provided with two chartered passenger trains, one CPR and one CNR, with adequate food for the journey back to Vancouver.

All this was accepted. Many men took advantage of the offer to go back to their own provinces, some as far away as Nova Scotia. Some took tickets to Toronto where they eventually did join an unemployed march to Ottawa, thus completing what they had originally started out to do. The original family, with some additions, finally left Regina on the two trains, each provided with $5000 worth of food.

We were still united. We were still the Relief Camp Workers. It is true that we left behind in Regina many of our members in jail, in hospitals, but before we had left, these comrades and their destiny were in good hands. The Canadian Labour Defence League had assumed the legal defence of our comrades who were arrested, and the welfare of our comrades who were in hospitals. They could not have been left in better hands.

Our trip to Vancouver on the cushions, luxurious, bountiful, was uneventful [and] short in terms of minutes and hours, but actually much water had flowed under many bridges. Indignation was so universal that, by the time we arrived in Vancouver, negotiations were already underway to transfer the Relief Camps in B.C. to the provincial government and institute a wage scale of 40 cents per hour which was the provincial maximum...

The province was taking over from the federal Department of National Defence, and that the wages were to be 40 cents per hour, and that pending the total reorganization we would all be granted relief in Vancouver.

We had won a temporary victory and most of us joined the longshoremen on their picket line. Gradually the situation straightened out for us, the camps were absorbing the men under a new jurisdiction at 40 cents per hour. Most of the camps were under the jurisdiction of the Provincial Forestry Department with men employed building park and camping sites which are household words today, 25 years afterwards: Stamp Falls, Alberni; Englishman River, Campbell River, Elk Falls, all on Vancouver Island with many, many more on the Mainland.

I was drawn into organizational work for the miners of British Columbia and early in the year of 1937 I volunteered and joined the International Brigades of working men who went to the aid of the Spanish Republic in its unsuccessful fight against [an] international Fascist invasion.

The struggles of the Canadian unemployed, and particularly the B.C. unemployed, did not end with my severance from their ranks. In fact, their fight did not end until the start of the Second World War when, of course, all unemployment in Canada ended...

That is the end of my story of the (B.C.) Relief Camp Workers. If this narrative is ever published and read by the present youth of Canada, and if it furnishes any hope of inspiration in the coming crisis of unemployment, then it has been worthwhile writing it.

R. Liversedge,

Lake Cowichan,

B.C.

* * * * *

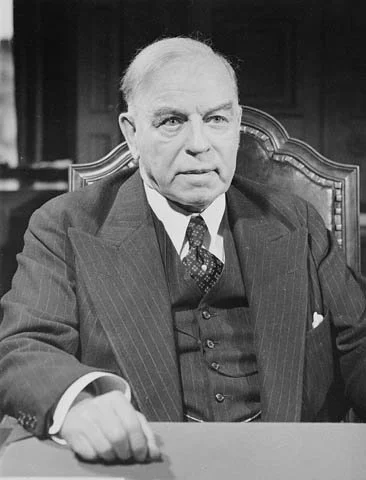

By 1935 most Canadians were disenchanted with the Bennett government’s handling of the economy. Five months after the On-to-Ottawa Trek, the Conservatives suffered a landslide defeat and weren’t returned to power until 1957.

Prime Minister R.B. Bennett “remained leader of the Conservative Party until 1938, when he retired to England. He was created Viscount Bennett, the only Canadian prime minister to be honoured with elevation to the peerage. Bennett is ranked as a below-average prime minister among historians and the public”.—Wikipedia

Liberal leader William Lyon Mackenzie King was disappointed at losing the 1930 federal election but later admitted to being relieved that the Conservatives had been stuck with trying to deal with the Depression. —Wikipedia

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.