‘On-To-Ottawa Trek, 1935

(Part 1)

Eighty-seven years ago, thousands of unemployed couldn’t protest with trucks—they had no gas. So they ‘rode the rails’ eastward from Vancouver, determined to present themselves directly to the R.B. Bennett government in Ottawa. They made it as far as Regina where they were met with mounted police and bullets. www.labourheritagecentre.ca

I seem to recall having recently presented you with a case of history, sort of, repeating itself.

One could argue that the ongoing (as of time of writing) truckers’ protest in Ottawa is another case of deja vu. The precedent, for those of us who know even a smattering of Canadian history, is the 1935 On-to-Ottawa Trek of the unemployed in 1935.

This was mid-Depression, the worst ever experienced by Canadians.

There, all similarity ends. Not only in the protesters’ modes of transport and their stated aims, but particularly in the way the two protest movements have conducted themselves, and the responses to date by various levels of government.

We’re talking the difference between day and night.

In the 1960s, Ronald Liversedge who’d been one of the leading participants of this epochal event in Canadian history, was living in Lake Cowichan when he wrote Recollections of the On-To-Ottawa Trek, 1935.

Originally self-published in a cheap and crude format “produced by volunteer labour,” it was reissued in standard paperback format in 1973. Despite the author’s pro-labour viewpoint and his personal participation, it’s considered to be one of the best accounts of the events leading up to and during the protest that ended in tragedy for some of the protesters and a policeman.

I hope the fact that my copy is slightly dog-eared and soiled means that it has been read repeatedly.

It’s easy to think that, because Ronald Liversedge was one of the ‘ringleaders” of this cross-country protest, his account is suspect. The fact is, it has a distinct aura of truthfulness and most historians appear to accept his version as being honest and incisive.

It should be required reading in Canadian schools.

While reading this week’s Chronicle, compare the circumstances described by Mr. Liversedge to news accounts of those which have led us to the current debacle in Ottawa and at crucial border crossings.

If ever there was a time to learn from history, this is it!

* * * * *

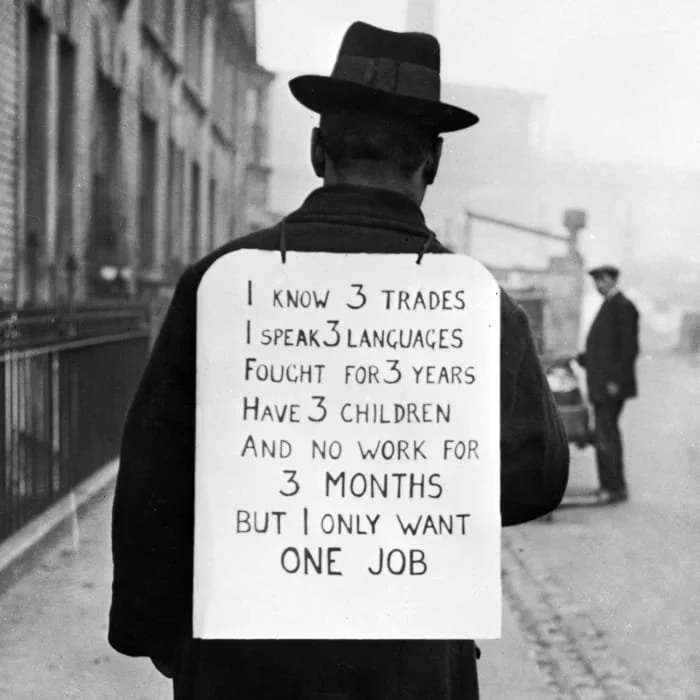

In 1935, a sign waving ‘protester’ said it all in just three words: WE WANT JOBS.

Note: jobs. He wasn’t demanding his ‘right’ to defy science and general society by insisting upon being allowed to indulge in all the benefits of Canadian citizenship that we’ve come to take for granted during a time of pandemic.

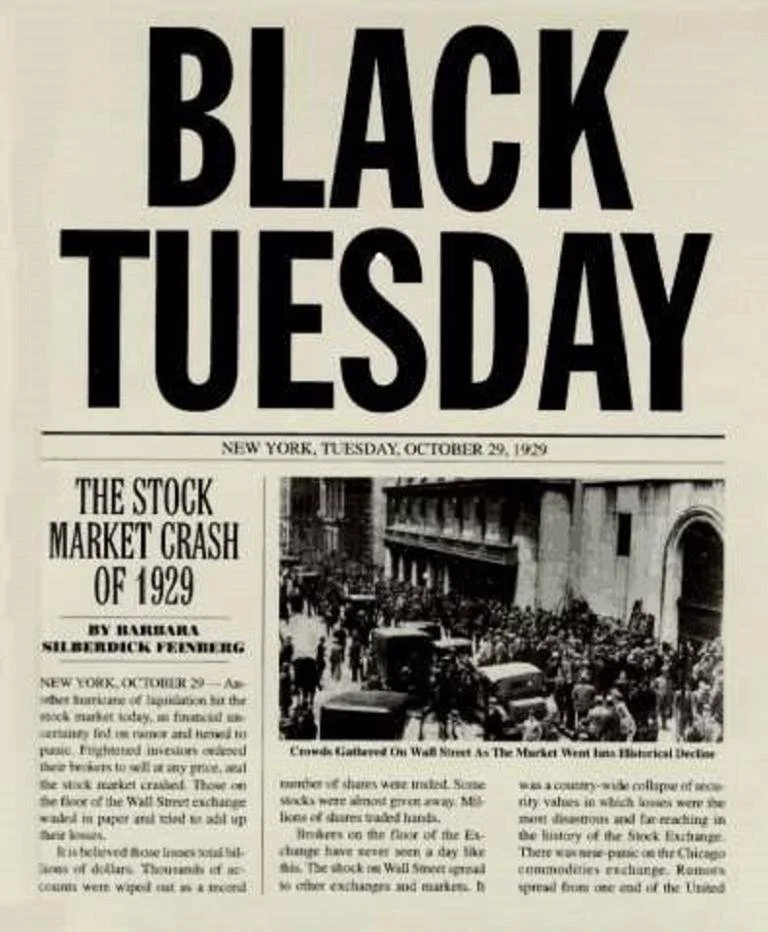

It all began with the crash of the stock market on ‘Black Tuesday,’ Oct. 29, 1929. —George Eastman House Collection/Wikipedia Commons/Public Domain

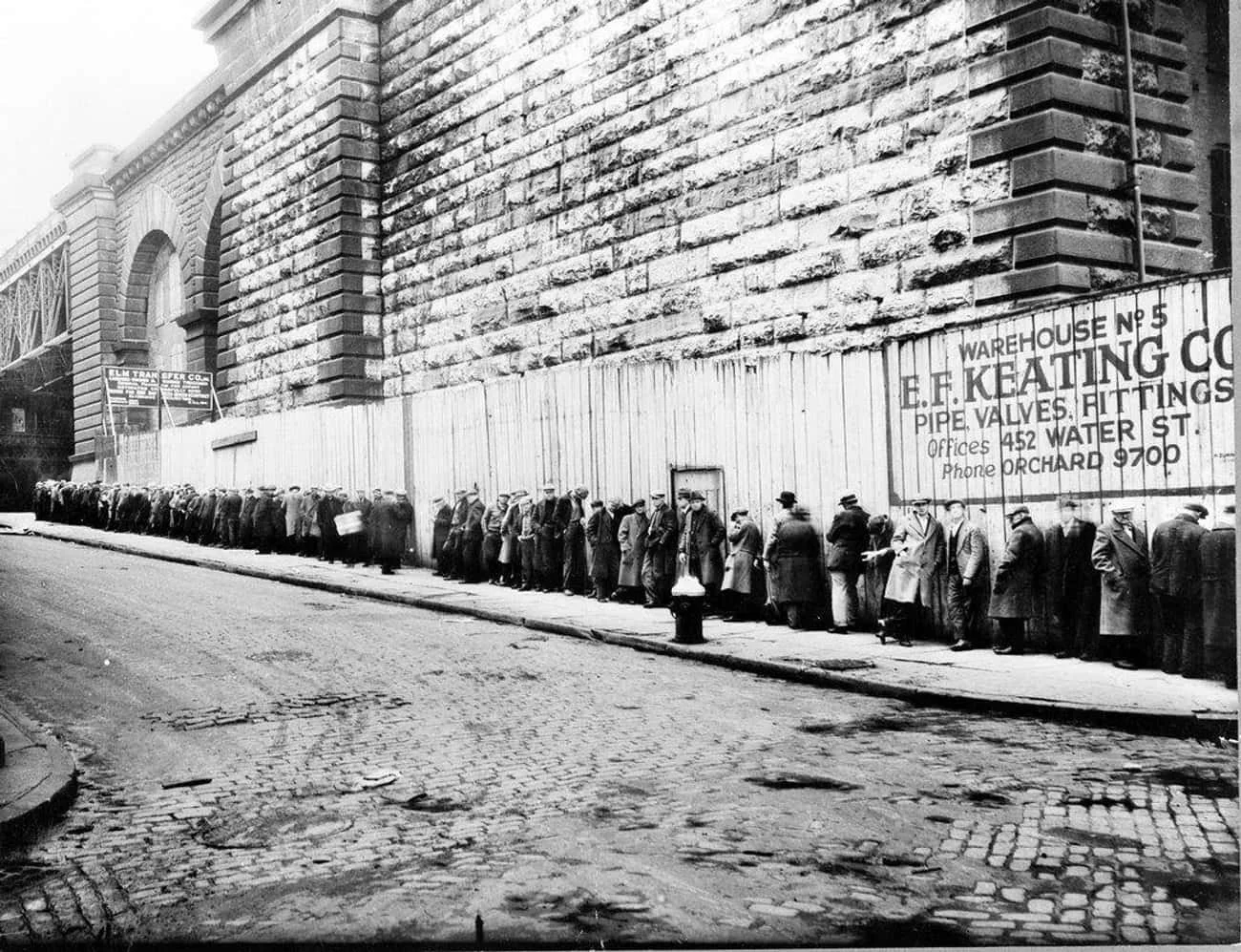

He was one of the millions of victims of the so-called Great Depression of the Dirty ’30s, the worst economic downturn ever endured by the western world. A time when 30 per cent of the Canadian labour force was out of work, when one in five Canadians were dependent upon government relief for survival.

A 10 year-long drought when the unemployment rate remained above 12 per cent and didn’t begin to fall until Canada began to prepare for the Second World War in 1938.

Then, with war looming, money and jobs became available for the asking. No longer were the legions of unemployed and destitute single men, many of them veterans of the First World War, on their own and at the mercy of a provincial and federal government that answered their needs with policed internment camps, board and 25 cents per day allowance in return for their working on public roads, fighting forest fires, and the like.

They were needed again.

So, let’s go back to the summer of 1935, to B.C.’s summer of discontent when the pot finally boiled over and the On-To-Ottawa Trek was conceived. It started in Vancouver in the sixth year of Depression. Our narrator, as noted, is former Lake Cowichan resident Ronald Liversedge. This week he sets the stage for what would become one of the key events of Canadian history. I’ve kept editing to a minimum.

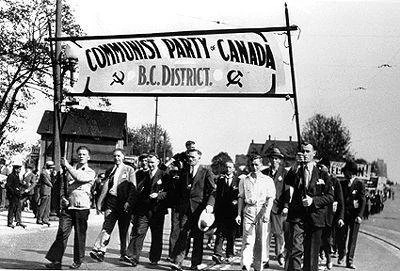

Please note: My sentiments as expressed above don’t mean that I subscribe unequivocally to Mr. Liversedge and company’s beliefs and actions. I would also point out that the participation of acknowledged Communists in the Trek to Ottawa in no way corrupted the protest; it was a march by the unemployed of all political persuasions to demand that the federal government do more to meet the suffering of millions of Canadians.

* * * * *

(Left) A year into the Depression, the Mackenzie King Liberal government’s sluggish response to its ever-increasing severity led to the party’s defeat at the polls to (right) R.B. Bennett’s Conservative party. Their failure to create jobs or to implement programs to ease living conditions led to Bennett, a multi-millionaire, being held as personally responsible for the hardships endured by millions of Canadians. It was decades before a Conservative government was again returned to office in Ottawa. —Wikipedia photos

...Although it has been claimed in later years by some economists, that from 1934 onwards, there was an upswing in the world economy, I don’t think that anybody in B.C. or Canada noticed it at the time, or at any time before the start of the Second World War...

Millions of people in the world were hungry and at the same time, thousands of tons of coffee were dumped into the sea off the mouth of the Amazon River; the U.S. government paid the farmers a small dole not to sew any crops. Cotton and wheat were burned up; three million pigs were slaughtered and destroyed in the United States, fish which the people could not buy thrown back into the sea. Fruit was left to rot in the orchards.

This was the Depression, and I am convinced that Capital could not have recovered from it except by starting the Second World War. The people would finally have established socialist governments all over the world, a state which the war postponed for a few decades.

That winter [1934] and up to our big strike in the spring of 1935, I worked on [the B.C. Relief Camp Workers Union] paper. There were more unemployed in Vancouver and much activity. There had been another hunger march in Victoria, and there were many public mass meetings taking place. Our union office was busy. Smokey and myself made some trips out to the [government relief] camps (via the usual route) reporting union progress.

The men in the camps had rapidly recovered from the December strike, [staged to protest living conditions in government work camps] and there was a definite feeling abroad that the spring would see the general strike.

Some incidents of that winter in Vancouver which come to mind: I remember the Armistice Day parade, a cold dreary November day, the small official parade, a handful of servicemen, some officers, a few veterans with a padre. Around Victory Square but apart from that ceremony, the crowds of unemployed, hundreds of them veterans, looking cynically on, when up on the dome of the Dominion Building, there appeared Padre O’Niel from the Workers’ Ex-Service Men’s League.

Through a huge megaphone Paddy addressed the crowd: “Work and not hypocritical services’ work, so that we who once proudly served our country can live decently!”

There were two elevators in the Dominion Building, and as four policemen were ascending in one of them to arrest Paddy, he was descending in the other one to mingle safely in the crowd.

I think it was during that winter when the Nazi [light cruiser] Karlsruhe visited Vancouver and Mayor McGeer and the Council extended a civic welcome to the officers and the crew. A civic banquet was laid on for them at the Moose Hall. The angry citizenry of Vancouver, at least many hundreds of them, were at the Moose Hall before the Nazi crew arrived, and an anti-Nazi demonstration developed, some people arriving steadily.

The Nazi sailors were allowed to enter the Moose Hall unmolested but had to face some booing and embarrassing questions. Soon the Cossacks arrived and I think the largest part of the foot police. During the petty vicious melee that followed, Big Red, of Boundary Road fame, being pushed in the back by a policeman, turned, and with a mighty shout, felled the policeman on the sidewalk.

Disdaining to make himself scarce, Red calmly awaited the four club-swinging police who came to take him. Some of us rallied to his defence. It was a bang-up fight and took the horsemen to finally aid in the arrest. Red got 30 days.

Working for their ‘dole,’ 25 cents a day, meals and a bed, what these men wanted were real jobs with which to support themselves and their families. — picryl.com

One day at the union office, we received in the mail what looked like a large rolled up newspaper. When the parcel was opened up we found a roll of about 25 large sheets of manuscript with 100s of names listed. It was the “secret” lists of the subversives amongst the many camp workers.

One of our members, a French Canadian, had somehow during the December strike, managed to get a job as a clerk in the Relief Camp administration offices at Hope. During the course of his work, he came across the documents and appropriated them and mailed them to the union office in Vancouver. The information opposite each name was very brief: date and place of birth, and in a few instances, name and address of next of kin, then, agitator or organizer, or both.

There were 100s of names including everybody we knew and ourselves. Many of the boys recognized themselves listed half a dozen times, under the various names that they had used from time to time.

We hung the lists in a prominent place in the office To the boys dropping into the office all day long the lists for some reason or other caused the greatest hilarity. They would paw through them by the hour, shrieking with laughter as each name was recognized. Having to try get some work done in the office, I was glad when the lists were pawed finally into shreds and were thrown in the garbage.

And as the time rolled along to that day in the spring of 1938 when the call went out and from all corners of the province the Relief Camp Workers converged on Vancouver to the battle cry of, “Hold the Fort,” commencing the epic strike which merged into the “On-To-Ottawa” trek.

STRIKE

When the camp workers arrived in Vancouver, no time was lost in starting on the type of organization which all knew would be necessary if we were to achieve our demand of negotiating with the government. In the past, since the inception of the slave camps, blacklistings, etc., we had constantly tried for negotiations with the federal government by correspondence and by pressure on local authorities in B.C. [only] to be just as ignored...[as] by Ottawa.

The men were determined not to return to the slave camps, and moreover as from now on, the procuring of all our food would depend upon our own organized effort; it was felt that the struggle might well be a protracted one. We had never had any cause in the past to trust any authorities or governments, always promises to us had been observed in the breach: “Go back and stay in the camps and we will get things done for you.”

There had been no illusions left amongst the camp workers for a long time. Everybody amongst us knew that we had to use pressure to gain relief, we would have to be well conducted, and to exercise self-discipline, and to maintain our unity of purpose.

Our numbers fluctuated all through the strike, but close to 4000 men came into Vancouver. All the men from the camps did not come into Vancouver; great numbers headed for the Prairies and back east, but the camps were closed, and there were quite sufficient men in Vancouver to carry on the struggle against the slave camps. The type of organization which finally evolved after two or three weeks of strike in Vancouver (features being added on as the necessity arose) was semi-military in character and obtained until the end of the strike.

Three halls had been acquired (I think at one time there were four), and the strikers saying as close as possible in their camp groups were divided between the halls.

This man’s sandwich board says it all. —www.history.com

The men in each hall constituted a division, and the hall was to be their headquarters throughout the strike. Two of the halls were on Cordova Street, and housed Divisions One and Two, and the Ukrainian Labour Temple was loaned to us for as long as it was needed and housed Division Three. My division in town [known as the G Men] were divided between the divisions.

As the men settled in, each division selected its leader, chairman, secretary, marshal, who took charge of he parades, looked after the general deportment of his boys, and watched out for the security of his division in general. Also, members to the general strike committee were elected.

The strike committee comprised some 60 members, and met at a hall on Hastings Street West. The strike committee met every morning at nine, and the divisions met every afternoon at one to discuss the business brought down from the strike committee, and also anything related to its own affairs. Runners were elected and stood by at all times to take any message to the other divisions if the need arose.

This was the set-up at the start. As we would in some things, be working with the unemployed organizations in Vancouver, we invited Arthur Evans who was a leader of the unemployed there, to sit in on our strike committee, and after a time we elected Evans to assume leadership of our strike.

George Black who was chairman of the strike committee was second in command to Evans on the trek to Ottawa three months later.

Here a brief word on Art Evans, or Slim, as he was known to every relief camp camp worker and to most of the working class at the coast at that time. He was described in the Vancouver Press as a Communist or Bolshevik agent, who was receiving a huge salary from Moscow to incite the people of Vancouver to riot on the streets while he himself looked down from the security of a high room up in a building on Hastings Street,

The only true statement in the description being that he was a Communist.

The common enemy, unemployment, and what was perceived as uncaring governments of all levels, made ‘strange bedfellows’ that included the Communist Party. —www.sutori.com

I had known Slim for a while before the strike, and through the strike and trek for many months after, I worked very closely with him. It didn’t take that long to understand his character.

Evans was a dedicated man, dedicated to the uplift of the working class, dedicated to Communism, so much so that he was like the absent-minded professor. Nothing outside of the working class struggle held any interest for him.

Slim had experienced police clubs and prison, and to him it was just a nuisance, in that it took him away from his work. During the “On to Ottawa Trek,” some of us would be having to remind Slim to eat once in a while, and as for sleep, he got less than the rest of us on the central strike committee, and some of us never ever got more than four hours in any 24.

Add to this Slim’s brilliant mind, and that his middle name, if he had one, should have been audacity, and there would have been Arthur Evans.

Our first big task after organizing our divisions was the raising of sufficient money to establish our own relief, and for this the majority of the men decided on a tag day in Vancouver. The date was set for the first Saturday. Application was made a few days ahead to the Vancouver City Council for permission to hold the tag day and, as was expected by all, permission was refused.

This was a tactical error on the part of the City Council, as we had three days to advertise, and we welcomed the opportunity to put on an illegal tag day, knowing it would be more effective, that people would flock into the city from all the suburbs to see what the reaction of the police would be.

By the Saturday morning all was ready.

The tag day headquarters was a large room up one flight of stairs on Hastings Street opposite the City Hall which was then in the Holden Building. Here were the general staff with maps of all the city streets and intersections, lists of taggers, times of relieving shifts, volunteer workers from the Vancouver unemployed, preparing cans, girls ready to count the money as the full cans came in, blackboards on the walls to list the amounts of different periods during the day, the inevitable coffee makers, and hovering above all the activity with a word here and a suggestion there, was Slim Evans with a happy smile on his long, lean countenance.

The plan was to cover all the main streets and intersections in the city, all the suburbs which had shopping centres, and the City of new Westminster.

The divisions were mobilized, and if the police started making arrests, then as each man would be picked up, another would take his place. We had enough men to keep the police busy all day.

In cars loaned by people in the city, the Flying Squads patrolled the different routes, to phone in word if anyone was arrested, to replace any tagger who was sick or had to be relieved for any other emergency, and to hand out empty cans for full ones, if there were to be any full ones.

As it turned out, there were plenty.

There was a lot of waiting in bread lines and employment lines during the Dirty ‘30s. —exit78.com

At 8 o’clock on that Saturday morning, the tag day opened, every man at his post and every corner covered from Point Grey and through Vancouver to the Burnaby’s to New Westminster. Anybody expecting any excitement in the way of physical clashes with the police were to be disappointed.

At 8 in the morning the chief of police had five taggers picked up; their places were immediately filled, and in an hour or so we were able to obtain their release. By 9 o’clock the cash was rolling in in a steady stream that went on until dusk of the evening.

Vancouver was with us.

In nickels, dimes and quarters (for it was the Depression) Vancouver was with us to the tune of $4600 [$97,158.27 in today’s dollars]. That day the people of Vancouver showed in no uncertain terms where they stood on the question of the slave camps.

In New Westminster around mid-morning, the Chief of Police ordered his small force to arrest the taggers. The Flying Squad phoned in, “arrests taking place here, send immediately 100 men and have another 100 stand by, we are going now to interview the Chief of Police.”

The captain of the Flying Squad told us that evening what had transpired in New Westminster.

He said that after phoning in for reinforcements he had gone around and replaced as many of the arrested men as the Flying Squad allowed, and then with one man had gone to the police station.

Here there were 25 taggers, and the captain said it sounded like 2500. These boys were in a happy, hilarious mood and had refused to surrender their cans. The Chief was looking a bit worried, but his dander was up. He was telling the boys, “You’ll all go down for this. I run the law here, and I’ll have no bums tagging in this town.”

“Oh, yes you will, Chief,” butted in the Captain of the Flying Squad. “There’s a 100 men on their way and just about due in.”

“You’re lying,” said the Chief. “And, what’s more, if you don’t scram you’ll go in, too.”

Just then the 100 arrived, all trying to squeeze into the police station, with the first man yelling, “How many hundred can you accommodate in here, Chief, because there’s quite a few thousand more in Vancouver waiting for a call.”

The Chief realized defeat and roared at the jailer, “Turn every damned one of them out!”

After that, everything went smoothly.

It was a happy day, like a main occasion. Vancouver resounded to the rattle of the nickels and dimes, the shaking of the cans. All the boys recounted wonderful conversations with the people on the streets and the messages of encouragement were very heartening.

The Flying Squads had only one complaint and that was that many of the young taggers refused to exchange full cans for empty cans at their place of tagging, but insisted on being temporarily relieved, and driven into headquarters where they could personally deliver their full cans, boast of having it filled it in an hour and a quarter, and it was their third or fourth can that day.

The girls who were counting the money would congratulate the young fellow, telling him that he was the best on the beat, and his effort up to date constituted a record for the day, and back would go the guy to collect some more.

In the late evening I was at the headquarters, having tagged Granville Street most of the day. There was a big crowd of people there, the girls were quickly compiling the amounts from the incoming cans and handing the scores to the girl at the blackboard.

Suddenly [she] cried out, “Oh, this puts us over the $4000 mark!”

There was a buzz of congratulation and then Slim Evans said, “Comrades, that’s a lot of dough. We must have protection for it. You can never tell, you know,” he said with a twinkle in his eye, “we could be held up.”

He grabbed the telephone and amidst the laughter of the crowd, asked for the police station. Getting connected withe the Chief, he explained that we had gathered a lot of money and there was more coming in, and as we felt uneasy about it, would the Chief send over a guard?

Shortly afterwards, two solemn faced policemen arrived to act as guards. They seemed surprised at first, at the crowd, the bustle and enthusiasm. They were given chairs and settled down comfortably. As every can was opened and the contents poured on the counting table, Evans would holler, “Moscow gold, the real stuff!” and going over to the policemen would say, “There, you fellows, you’ve heard about it and now you see it for the first time.

“Don’t forget to tell the Chief that you were actually there and saw the payoff.”

The guards stayed until the last nickel was brought in, and then escorted it to the police station for safekeeping until the Monday morning.

The tag day was a success; it gave us a breathing spell free from economic worry for 10 days or so, even with the number of men in our ranks, because many hundreds of men who still had a dollar would not apply for strike relief until they were absolutely broke. We could now go about our business of conducting our strike and perfecting our organization...

* * * * *

Next Week: Up to that point in 1934 the unemployed workers who’d gathered in Vancouver were working towards a general strike in the coming year. There was no thought of a Trek-To-Ottawa—that would come after all their attempts to bring the provincial government to the bargaining table failed.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.