‘On-To-Ottawa Trek, 1935 (Part 2)

In trying to compare the ‘On-To-Ottawa Trek’ by thousands of unemployed men in 1935 to the continuing occupation of Ottawa and the blockading of crucial border crossings by anti-vaxxing truckers and their supporters, this week’s Chronicle is based upon the “recollections” of onetime Lake Cowichan resident and Spanish Civil War veteran Ronald Liversedge.

As we saw last week, in 1934, preparations were underway in Vancouver for a general strike across B.C. Thousands of single men had rebelled against government-run relief work camps where they’d laboured for their board and 25 cents a day.

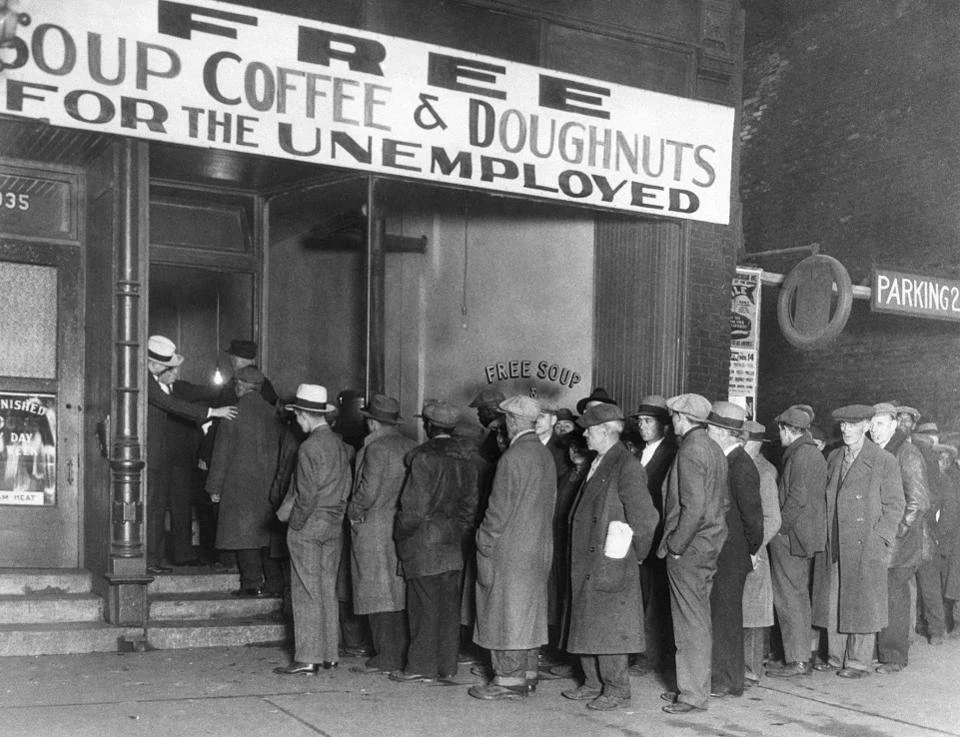

—Public Domain

What they wanted was real work—real jobs with pay cheques that enabled them to live their lives as productive and contented citizens, to be able to look to the future with hope and optimism.

But this was the Great Depression, the Dirty ‘30s.

The capital systems of the entire western world had foundered after the stock market crash of 1929. Canada was no exception. As noted last week, 30 per cent of the Canadian labour force was out of work, one in five Canadians were dependent upon government relief for survival, and the unemployment rate remained above 12 per cent until Canada began to prepare for another world war—and workers were again wanted.

For most of 10 years, federal and provincial governments met the challenges hesitantly, uncertainly, often reluctantly, often with downright cavalier and niggardly responses. The result was social unrest such as Canada had never seen before.

Until now if one wishes to equate what just happened in Ottawa, the Victoria Parliament Buildings and at border crossings to the events of 1934-35.

Please note: In recounting these historic events, l would make known that, although I’m generally empathetic, my own beliefs don’t totally agree with those of Mr. Liversedge and company of 87 years ago. I’d also point out that the participation of acknowledged Communists in the Trek to Ottawa didn’t corrupt the protest.

It was a march to demand that the federal government do more to meet the suffering of millions of Canadians—including many of those who were employed in demanding and underpaid jobs.

I also remind readers that Liversedge’s account of the Trek-To-Ottawa is accepted as being historically accurate as viewed from within the unemployed protest movement.

Last week, we saw how the organized unemployed raised funds through a phenomenally successful Tag Day in Vancouver, New Westminster and the Lower Mainland. Liversedge, after defending strikes as the last-ditch weapon of frustrated workers—“...Only under great provocation do workers engage” in work stoppages—resumes his firsthand account..

(Because of the length of the Liversedge book this short series in the Chronicles is condensed.)

* * * * *

It is impossible to list from memory all our activities, our committees, our meetings, our militant pressure to gain relief, etc., but what is possible to relate is the solidarity, the unbreakable unity between the Relief Camp strikers and the common people of Vancouver and the Lower Mainland.

The people as a whole took the camp strikers as their own, extended the protection of their vast numbers to them, in meetings and demonstrations on the streets, and at the same time recognized and acknowledged, in the wonderful organization, self-discipline, and exemplary conduct of the camp workers, a force whose example could lead to the realization of their dreams. Dozens of requests came in from employees of factories and shops, asking for our aid and advice in their organization into a trade union.

The success of our publicity campaign (combined of course with the general antipathy toward the relief camp system) can be judged by the mass rally against the relief camp system, called by the relief camp strikers within a month of our arrival in Vancouver, at which 15,000 people attended. It was held in the Arena at the Georgia Street entrance to Stanley Park.

The Arena...had a seating capacity of 15,000, and there were no empty seats that night.

On the platform, at our invitation, were representatives from the Communist party, C.C.F., trade union officials, churches, Women’s Labour League, and many more. There was one ex-mayor of Vancouver, old L.P. Taylor, and Dr. Telford of the C.C.F., who had been or was to be a mayor of Vancouver, also spoke.

There was a great degree of working class political unity achieved around the relief camp strike than ever before or since.

Our most spectacular committee, or I should say, group, were the pickets. Comrade Sands was a unanimous choice for Picket Captain. [He] accepted the job on a provision that he pick his own men and that the group of 40 was to be considered a permanent picket squad for the duration of the strike, to be excused of all other duties, and to take care of all situations calling for special picket work.

This ex-German soldier and Communist [who later met his death in the Spanish Civil War] would have shared his last shoestring with you. He had still a little of the stiff back, ramrod-ism, of his early training about him but there was a clamour to get onto his squad. Sands picked his picket squad, all six-footers, and before long, I am sure, they must have resembled Sands’ old army platoon in every respect except the goose step, and, believe me, they loved it.

The relief offices in town were picketed constantly [because] anybody applying for relief would be given papers and transportation to a relief camp. The pickets would advise them to hand over their transportation and send them down to a strike headquarters to join the strikers. Most of them would do this. The very few who refused always lost their transportation on the way to the railroad depot.

...Two outstanding events happened in the last part of May just before our strike shifted from Vancouver to the box cars. The notorious Hudson’s Bay store “riot,” and the Day of the Museum when by a brilliant manoeuvre, we seized the museum, rallied 50,000 people on the downtown streets for over eight hours, and forced seven days’ relief from the City of Vancouver for all our members.

Short of jobs the unemployed needed relief as provided by this soup kitchen. —Public Domain

While I write this, I have here a copy of [Maclean’s Magazine] for April 1960. In this copy there is an article on the “Dirty ‘30s” written by a Mr. Frank Croft. I quote: “In 1935, Vancouver got a taste of real violence, when 300 unemployed stormed up Granville Street, smashing shop windows. They entered the Hudson [sic] Bay Company store, and smashed and overturned every showcase on the ground floor before police could stop them. The reason was that they didn’t like being ‘unemployed.’” End of quote.

Lies! Lies! and Lies again! and still they lie!

Here is what happened that day of the [Hudson’s] Bay imbroglio, and Gerry McGeer’s Riot Act.

The three Divisions of strikers were out on a routine march, each division taking a different district. The police dearly loved a compact target, one on which they could converge from all sides, surround and bash into submission. (I leave it to readers to judge Mr. Liversedge’s credibility in making such a charge. —Ed.]

We always tried to avoid giving them that opportunity. Our objective was not civil disturbance, but the abolition of the slave camp system. These marches were for publicity purposes to keep up the morale of our forces, enhance our esprit de corps, and proved on the whole a healthy influence during our strike.

On the day of which I write, my Division, Three, marched west on Hastings then south on Granville with no windows broken despite Mr. Croft. At the head of the Division chosen as the leader of the march for that day, my friend Jack. It must be mentioned here that due to previous marches and demonstrations all the large department stores had guards at each of the doors.

We marched in good style, singing our songs and chanting our slogans. At Granville and Georgia, Jack swung the Division east on Georgia, and then north on Seymour, and right away noticing that the Seymour entrance to the Hudson’s Bay Store was, for some unknown reason, unguarded, he wheeled left and marched the Division onto the main floor of the store.

It was a golden opportunity not to be passed up, and for anything that followed, the only part of the blame that the relief camp workers assume was in making the tactical error of remaining on the main floor, and thus allowing the stupid police to be tempted to evict us.

Again, contrary to Mr. Croft, we were in the store for over 30 minutes before the police arrived. Jack had made a nice speech to the shoppers which was well received, another comrade said a few words, and we were actually on the point of marching out and back to headquarters when the police arrived. There were probably a hundred of them; they marched in and lined up opposite our ranks.

Immediately, a tense situation developed, the rank and file of the police detachment were very obviously nervous. There was no attempt at parleying, no depositions. There followed a period which lasted for over 15 minutes of staring each other down, with the police leaders seemingly studying their own chances of a successful eviction.

There could have been telephone conversations going on with police headquarters, but of that I have no knowledge, and I also do not know where the final order to draw batons and charge came from, but come it did, and resulted in a particularly vicious shambles. As usual, the relief workers did not submit peacefully, and despite the handicap of having no weapons, and facing big men with clubs, they put up a terrific resistance.

In the heat of battle, of course, some showcases were damaged. A special squad of police were detailed off to get Jack. Jack took a terrific clubbing and in his delirium lashed out in an attempt at self defence, and damaged a showcase, for which he subsequently served three months in Oakalla Jail.

Meanwhile, the battle raged, and we were being steadily evicted. More police arrived, about a dozen arrests took place, many of us received cracked heads and bruised bodies. I received four cracked ribs, and the police did not come off unscathed.

It would have been OK with us if the “do” ended at that. We had made an error, and taken a temporary defeat which to us was part of the business, but news had spread like lightning, the other Divisions were on their way to our defence, along with hundreds of enraged citizens. The whole police force were on the streets, the Cossacks were in action, and engagements were taking place all over downtown Vancouver.

The result was that the mayor, George McGeer, was rushed to Victory Square to read the Riot Act.

The camp workers lined up in their Divisions and in the interests of peace, marched off the streets to their respective headquarters and in the late afternoon, an uneasy peace once more descended upon Vancouver.

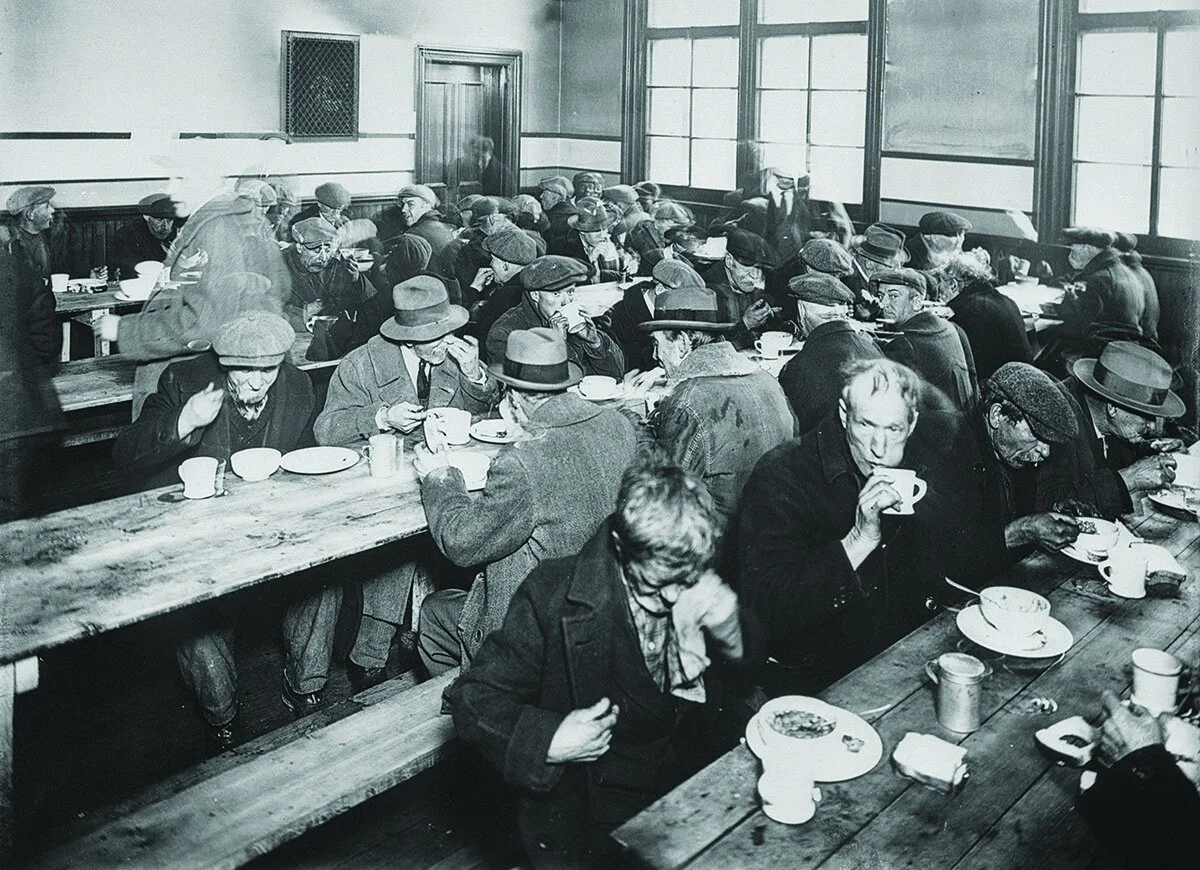

From the beginning of the relief workers’ protests the majority of Vancouver residents appear to have been sympathetic and helpful within their own limited means. —Public Domain

One of the camp workers, a brilliant cartoonist, drew a cartoon of Gerry McGeer on the steps of the Cenotah reading the Riot Act. Gerry in his ceremonial robes, but with wings and a halo and with a look of sanctimonious hypocrisy on his face, so real that it was startling. The publicity committee had the cartoon printed in thousands of copies which sold on the streets at five cents a copy, thus helping out our almost non-existent strike fund, and in a small measure easing a situation that was becoming desperate.

When we were at a desperately low ebb, our strategy committee finally came through with a scheme for forcing relief from the city which was, theoretically, foolproof, and which with its execution proved a glorious success. The day chosen was a Saturday, the Divisions met at their respective headquarters at 11:30 in the morning,

The program was for Division One to immediately march to Spencer’s Store, give the impression that they were going to enter [but], keep marching around, and draw the people together. Ten minutes later, Division Two would march to Woodward’s Store on a similar diversionary move, and as soon as we, Division Three, got word that the police had been diverted to [David] Spencer’s and Woodward’s, we would march in quick-time to Main and Hastings, enter the [Vancouver City] Museum over the Public Library, turn out all the occupants and barricade ourselves in.

As soon as we were ensconced in the Museum the other two divisions would inform the public of what had happened and start to move to Main and Hastings, drawing the people there in our defence.

There was intense excitement amongst the comrades, a cheer broke out, the motion was moved, seconded, and carried without debate. It was then explained that the strategy committee had assured us that with our strict cooperation, the scheme would not fail to being about the desired result.

As soon as a certain message was received we would move. The moment we leave our seats we must be in action, no hesitation on the sidewalk. The head of the Division will march immediately, keep close formation, and move.

Within seconds of receiving the word to act, Division Three in close-packed columns of four were quickly marching the five or six blocks to Main and Hastings, and a few minutes before noon we swung into Vancouver City Museum.

At the door of the Library, two of our members left the ranks, but we were close to 500 men who took over the Museum that day.

From the moment that we entered the Museum, we all felt reassured. There was a spirit of exhilaration that could be felt. Our strategy committee had picked wisely and well.

The museum, for a city the size of Vancouver, was rather small. One big room with angles and alcoves and corners crowded with historical, artistic, cultural and anthropological exhibits and artifacts, some good oil paintings and taxidermy, most of which was irreplaceable.

We were virtually sure that there would be no attempt to evict us. From the point of view of defence, there could not have been another building in all Vancouver so “ideally constituted.” There was one entrance which was also the exit across which a sliding steel grill-work kind of door could be drawn, and at the back of the room, a small door leading to a staircase, twisting and narrow, up which only one person at a time could come.

The museum also contained a telephone. As soon as we entered the Museum, our leader for the day, Tom, went to the woman at the information table where the visitors’ book also was, and told her we were taking over, to please take her papers and quickly leave, and not to worry, as nothing would be disturbed as long as there was no attempt to disturb us.

The caretaker or Curator came from around one of the corners, and was told he must leave right away, and he asked us to respect the exhibits, and was assured they were sacred to us as long as there was no attempt to evict us by force.

Meanwhile, the boys rounded up the very few visitors who were there and herded them out, and we drew the iron grill door and barricaded ourselves in.

All [this] time Tom had been busy on the phone, the first call being to contact outside informing them that we were in possession. That information was immediately transferred to the other two Divisions, at Spencer’s and Woodward’s, who instantly started a movement of the people to the Museum before the police woke up to the fact and finally disconnected us from our service.

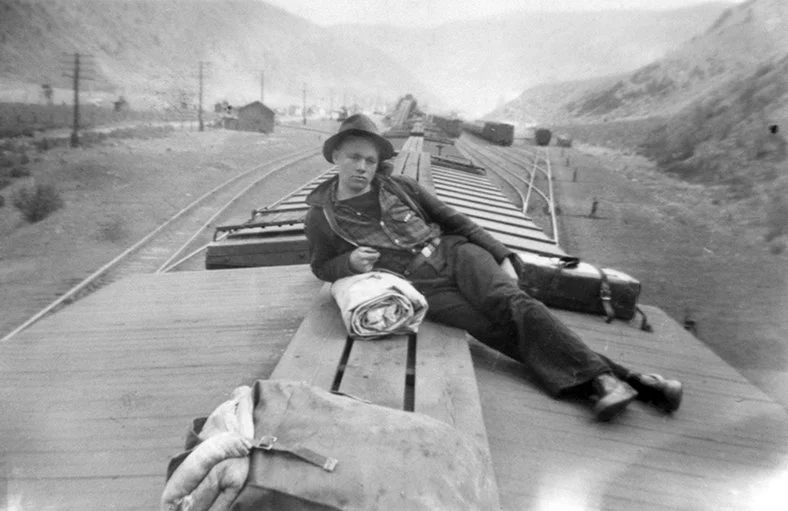

This is how many an unemployed man slept during better weather if he couldn’t find anything better.—Public Domain

While we were organizing our committees, guards, first aid, food, entertainment, etc., Tom was phoning up/ the newspapers, trade union offices, C.C.F. headquarters, language organizations, and anybody who would be interested, informing them of what [was happening].

At the same time, calls were coming in from our strategy committee, keeping us informed of what was happening outside. [Meanwhile] Divisions One and Two were rapidly drawing near, leading a crowd of stupendous proportions. Through an open window we could hear the noise of the approaching crowd; first, the steadily increasing murmur, then we could distinguish the Divisions singing “Hold the Fort,” and the roar of the crowds behind.

To us in the museum, although we had taken part in many crowded scenes on the streets, it was truly awe inspiring.

The Divisions had done a swell job. Within 15 or 20 minutes of us taking over the Museum, they had mobilized a demonstration of thousands of people outside.

It was the first wave of a demonstration comprising tens of thousands of people. There was no way of judging just how many people took part. Crowds were coming in from all over Vancouver all day; it is a fact that for eight hours (the time it took to break down Mayor McGeer) no traffic of any description moved over many blocks of downtown Vancouver.

In the Museum, one of our committees was to be responsible for communication with the crowds outside, furnish speakers, and be responsible for getting any donation of food which we knew would be forthcoming from the people in the street. This activity was to be carried out from a wide stone ledge outside the window overlooking the intersection and above the main entrance to the Library.

This means of raising the donations of food, etc., was a wicker basket and a couple hundred feet of light, strong line which was miraculously discovered in a corner of the Museum where there had been nothing the day before. The leader of this committee was Steve Brody, a very active spirit, a good speaker, a good comrade, respected by all.

I think Steve spent almost the whole eight hours that we were in the Museum on that ledge, speaking to the crowds below, whom I am sure, couldn’t hear a word, and working that basket up and down our lifeline. As the first crowds approached, Steve was already out on the ledge and giving back to us inside a running commentary on the scene below. We could tell by the agitation in his voice that the scene was stupendous.

We got word on the phone that a big part of the police force had moved into the Library below, cleared the building, and moved in tear gas equipment, but that there was a conference going on, the Librarian and Museum Curator were there, and more civic officials were arriving all the time.

This was understandable to us. We knew that, left to the police, there would be a shambles, but we knew that there were many influential people in Vancouver who would not stand for the museum being damaged, and we placed our faith in the people who were already congregating on the streets below.

We had a big guard [at] the entrance to the Museum, and it was thought that for the little back door and narrow stair up which only one man at a time could come, and he would have to come head first, that four men on guard would be plenty and a four-man guard was placed there to be relieved every every hour as long a we were there, and volunteers were asked for.

About a hundred men immediately clamoured for the job, and one of them who got on the first shift, Tony Costello, stubbornly refused to be relieved the whole time that we were in the building. I know that he was disappointed when it was all over and not one head had presented itself in that small three-foot opening. We were not disturbed in any way, and it was much later in the afternoon before we had our first visitors.

The noise coming through the open window was like the steady boom of distant thunder.

Soon Steve and his boys were steadily employed, hauling up and lowering down the basket. All the bake shops for blocks around were sending bread, pastries, and pies, the stores, the delicatessens and the cafes were contributing.

From the White Lunch down the street came gallon cream cans filled with hot coffee. People in the crowd below were sending up tobacco and cigarettes and candies and chocolate bars.

Later in the evening, when many of the boys in the Museum began to suffer with headaches (probably from overeating and smoking), a request via the basket quickly brought half a dozen bottles of aspirin tablets. We were overwhelmed with good things.

Some time during the afternoon there was a general alert when the guards at the entrance shouted to us that someone was coming up the stairs, and as some of us got to the iron gate, Col. [William Wasbrough] Foster, Chief of Police, and Oscar Salomen, president of the Longshoremen’s Union, walked across the lobby to speak to us.

Major-General William Wasbrough Foster, DSO, CMG, VPD (1875-1954), was a noted mountaineer, Conservative Party politician, businessman and Vancouver City Chief Constable in addition to his distinguished military career. —Wikipedia

It transpired that Col. Foster had asked Oscar Salomen to accompany him as a sort of witness and aide, and probably also with the hope that Oscar would be able to influence us to leave the Museum. Col. Foster stayed for a half hour, the conference took place through the iron grille.

He also made threats but pleaded with us to evacuate the building, pointing out that the situation in downtown Vancouver was dangerous, all traffic was blocked for many blocks around Main and Hastings, and that by our “coup” we had placed him and the police force in an impossible situation.

The Colonel appealed to our patriotism, said that some of us older ones must be ex-servicemen, and when we said that we were he appealed [to us] as one ex-soldier to another, asked us to restore order, said that his sympathies were entirely with us, but that we must not break the law.

We on our part told Col. Foster that as soon as were assured of relief for a short period that we would evacuate the building and disperse. We told him that he must be aware that we had been on the verge of starvation for some time, and that the City had a Relief Fund from which we were determined to get a few days’ relief.

The Colonel asked Oscar to speak to us and Oscar said that it wasn’t much use him speaking as he was with us all the way, and that we should be grated relief. He told Col. Foster that he would help him in every way possible but that the solution was to grant relief to the boys.

Finally the Colonel told us [Mayor Gerry McGeer] had disappeared and we said that he must use his police force to find the mayor and get him to sign the order for relief.

Two similar meetings were held later in the evening with similar results, and it was eight o’clock p.m. when Col. Foster] returned with the news that he had finally located Mayor McGeer at the Vancouver Yacht Club. The mayor had finally capitulated, had agreed to granting two or three days’ relief and had empowered the Chief of Police to carry out the negotiations with us.

We asked Col. Foster to bring up the chairman and marshal of the other two Divisions and that after a short conference with them we would give an answer. We asked Col. Foster to wait in the lobby for a few minutes and we opened the gate sufficiently to allow the representatives of the other two Divisions in and then called all the men together

There was only one thing to discuss, the numbers of days’ relief we would or could win. Three days was not enough and was not even discussed. As far as we in the museum were concerned we could hold out much longer, but our men outside had to be considered.

While we in the museum had been the hub of the scheme, the focus of the day’s activity, ours had really been a passive role. The other two Divisions on the streets had done a splendid job, drawing off the police, rallying the crowds, speaking from the Library steps, appealing for food for us in the building, going to the stores for donations for us; many of them had not eaten all day.

It was quickly decided that for a week’s relief we could vacate. At this we asked [Col. Foster] and Oscar Salomen if hey would come in and when they joined us we told them what we had decided.

Col. Foster offered six days, two meal tickets per day for every one of our men for six days. We accepted and discussed procedure. Col. Foster said that the minute we left and the crowd started to disperse, he himself with the authorized persons from the City, would meet with our Relief Committee and on the basis of our rolls would issue the meal tickets to our Relief Committee.

We asked for the Museum Curator and that Col. Foster be present when we handed over to the Curator. We sent a speaker down to tell tell the people that we had won relief, to thank them for their aid, and to ask them to disperse as soon as we left the building.

We told the Chief that we would line up our Divisions in columns and march out of the building and straight to our headquarters. He was willing, and finally, we got the Chief’s word of honour that the crowd would be allowed to disperse peacefully.

When the Museum Curator arrived, we asked him to check over the museum which he quickly did, and in the Chief’s presence, reported nothing was out of place, nothing broken or disturbed in any way. We asked if he would like us to leave a clean-up squad for the floor was messed up with cigarette butts, and he said no, that he was quite satisfied that everything was in order.

With that, we filed out, packing enough food with us for a couple of days, lined up in fours in the lobby, and commenced what turned into a triumphal march.

The police were lined up shoulder to shoulder on the stairway, but no remarks were passed. When we reached the open, the scene was staggering to us.

In the dusk of an early spring evening, as far as we could see in any direction, and jammed right up against the building, faces, thousands of faces, and then the roar of greeting; it was like a physical shock.

It was difficult to maintain our ranks, slowly making our way through that wildly cheering throng, the wonderful people of Vancouver, but how embarrassing to be a hero. Our meeting with the comrades of the other Divisions at strike headquarters was a joyful one, everyone filled with pride and joy at our victory.

It was our greatest success in Vancouver.

Like 1000s of other unemployed Canadians, this youth is riding the rods in search of work. —Public Domain

The occupation of the Vancouver Public Museum gained the unemployed a week of relief at the City’s expense. What then? They couldn’t impose further on the generosity of Vancouver citizens. Hence the desperate scheme to take their fight to Ottawa by hitching rides aboard trains—not in ones, twos or in small groups, but in the 1000s. —Public Domain

The recent occupation of downtown Ottawa by protesting truckers that prompted the invoking of the Emergency Act for only the second time in Canadian history is of such significance and has potential for future major expressions of public dissent that the Chronicles is comparing current events with those of the Trek to Ottawa in 1935.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.