‘On-To-Ottawa Trek, 1935 (Part 3)

We’re comparing the ‘On-To-Ottawa Trek’ by thousands of unemployed men in 1935 to the recent three-week-long occupation of Ottawa and the blockading of crucial border crossings by truckers and supporters virulently opposed to continuing pandemic legislation*.

(*See Editorially Speaking...)

Again, this week’s Chronicle is based upon the “recollections” of onetime Lake Cowichan resident and Spanish Civil War veteran Ronald Liversedge.

His memory isn’t infallible; by the 1960s he didn’t remember every name and he sometimes struggled with the actual sequence of events when so much happened about the same time. That said, his insider’s view, partisan though it is, is historically priceless.

I shall weigh it against more mainstream records in next week’s Conclusion.

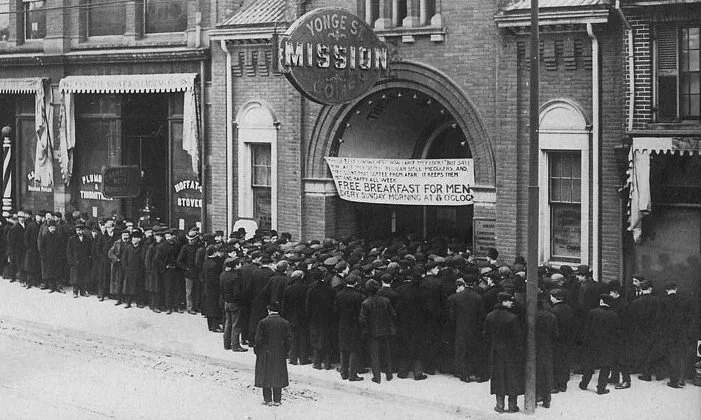

The current pandemic has devastated many small businesses but the resulting unemployment has been nothing like that of the ‘Dirty ‘30s’ when scenes such as this were commonplace in larger communities. Federally-run relief camps for unemployed single men were a token effort to deal with a national crisis. —Public Domain

As we saw last week, in 1934, thousands of Relief Camp Workers, as these unemployed single men in B.C called themselves, had rebelled against federally-run relief work camps where they’d laboured for their board and 25 cents a day. Most of them converged on Vancouver to seek relief from the City while they continued to press for direct negotiations with the Conservative government of R.B. Bennett in Ottawa.

The result was the spontaneous and violent occupation of Woodward’s Store then the brief but peaceful occupation of the Vancouver Public Museum in exchange for a week’s food vouchers from the City.

But Vancouver citizens, generally sympathetic, had their own families to feed and the unemployed’s morale began to flag. Taking their cause directly to the federal government seemed to be their last shot and those who agreed did so with renewed determination.

Editor’s Note: Because of the length of Mr. Liversedge’s firsthand account what follows is a much condensed version of his 1960s memoir. We resume with the momentous decision to go to Ottawa, their pit-stop in Calgary then fast-forward to their arrival in Regina where the stage was set for their clash with armed police.

* * * * *

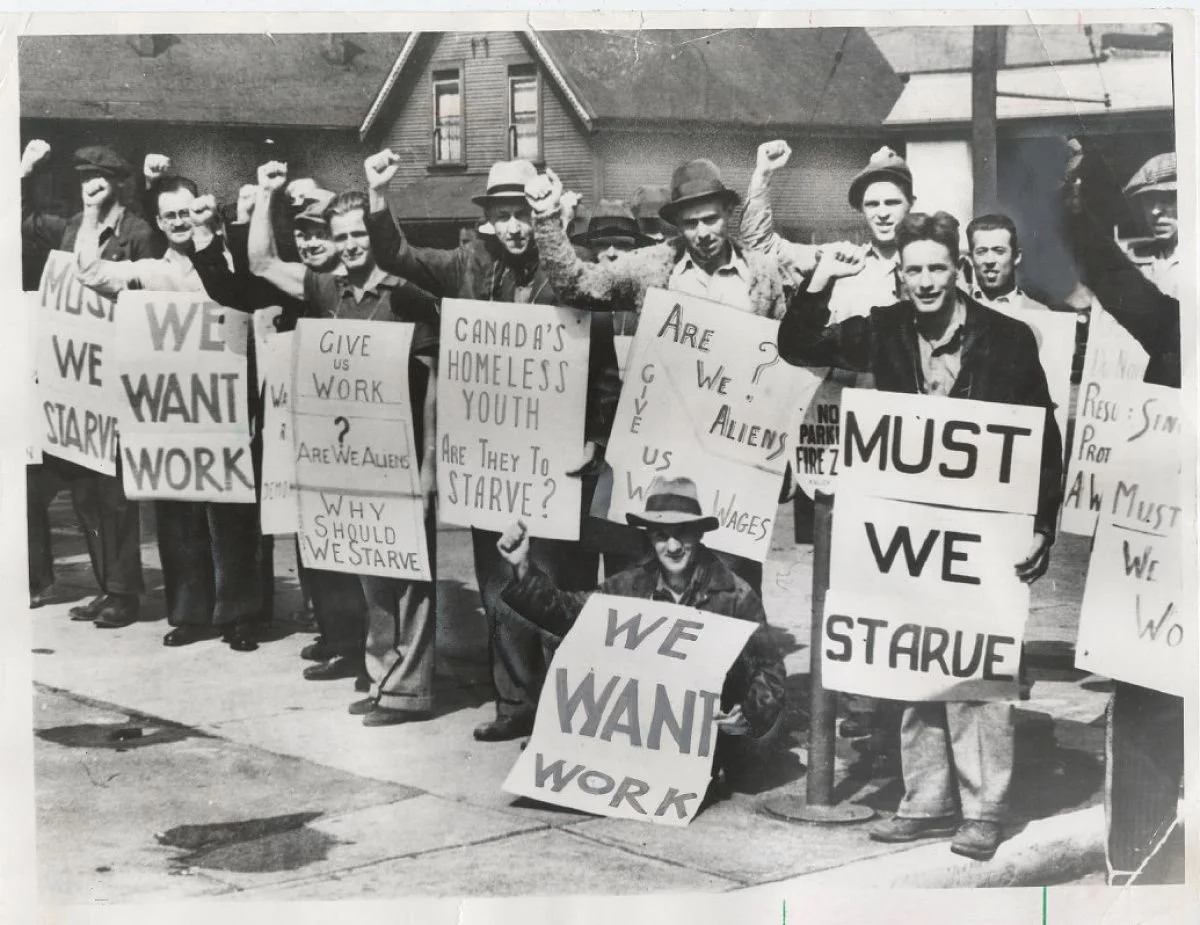

Even those fortunate enough to have jobs during the ‘Great’ Depression had to fight to keep their wages from being cut to the bone. —Public Domain

While our meal tickets lasted, we concentrated all our efforts on trying to bring about negotiations with the federal government, contacts with M.L.A.’s, M.P.’s, wires to Ottawa, all without success.

Soon we were facing hunger again, the people of Vancouver as good as they were, could not feed us indefinitely, thousands of them being on Relief themselves.

A feeling of apathy was beginning to be felt amongst the camp strikers, the strain of the long struggles was beginning to be felt, and we could not ignore the fact that we were losing many of our members.

It was in this atmosphere that a special night meeting of the Central Strike Committee was called to discuss the situation. At this meeting, after a lot of discussion which had offered nothing in the way of a solution to our desperate problems, a lull occurred when everybody present seemed to be trying hard to think of something to suggest.

Suddenly Slim Evans jumped up, and banging one fist into the palm of his other hand, said, “Comrades, we’ve got to get militant! We’ve got to get militant!”

“Militant!” said one of the boys, “What do you think we’ve been doing, Slim, ever since the strike started?”

Just then, another member took the floor. “Comrades,” he said, “I think that we are through in Vancouver, but I don’t think our struggle is finished. All the time, since the slave labour camps were established, we have been trying to get to the people who run the slave camps. Our oldest slogan is a demand for negotiations with the federal government. They won’t come to us, so I say, let us go to them. I hereby move that we go to Ottawa, to discus work and wages with the federal cabinet.”

The sheer effrontery of the motion startled the meeting, there was quite a lengthy silence, broken by [Slim] Evans, who seconded the motion. After the first shock of the motion was absorbed and the possibilities conjured up, the meeting was electrified, and discussion went on and on.

Every man in the room was a seasoned freight [train] rider, and not one would have hesitated at a 3000-mile boxcar trip if it was necessary—that is, as individuals. But it was a different thing for a couple of thousand men, maybe many more, before the end of the journey was reached. It would take a lot of organizing and publicity, and lots of determination on the part of the boys.

At the end of the long night’s session, the motion was carried. It remained for the Divisions at the next day’s meeting to endorse or reject. Since that time it has often been said and appeared in print also, that Slim Evans was the author of the motion which started the Trek. For the record, I can state that it was not so.

But I have to state that Slim immediately saw the possibilities with the “On-To-Ottawa Trek”. Slim...led it, and by sheer will power, guided it over its worst moments. From leaving Vancouver to the night he was arrested in Regina, Slim hardly ever slept, and never had time to eat much. His presence was always a stimulation to the rest of us.

The three Divisions endorsed the recommendations from the Strike Committee, and at a mass rally of all the strikers in a theatre at Main and Georgia...the Trek was officially launched, the name chosen, the “On-to-Ottawa Trek,” and the day set for our leaving Vancouver, June 3rd, 1935.

The Trek Begins

On the night of June 3, 1935, our trek got away to an almost subdued start, with around 1000 relief camp strikers lined up along the Canadian Pacific Railway tracks at the foot of Gore Avenue, waiting for the seaboard freight train which left Vancouver at 10:10 every night.

—Public Domain

There was an atmosphere of sadness hovering over the departure. Our ranks were drastically depleted. Reactions to our leaving Vancouver were varied. The working people who had been on our strike with us, in all our struggles in Vancouver, were genuinely sorry to see us go.

Officially, the mayor and council, the police, the Citizens League and most of the merchants could not hide their glee in our departure.

Also it was felt by the camp workers that the secret majority opinion of the people of Vancouver (including our friends) was that we had put up a great struggle but that we were at last defeated, and that our ranks would melt away soon after leaving Vancouver.

Public opinion was never in greater error, although at our first stop, Kamloops, the morale of the boys reached its lowest ebb, and it looked for a brief period as though there would be a breakaway of our numbers.

Anyhow, our farewells said, we boarded the CPR boxcars, keeping our group and Division formations, and huddled together on top of the cars, preparing ourselves for the long, cold ride ahead...

(Upon arrival in Calgary they demonstrated for meal tickets from the City.—Ed.)

There were plenty of people lining the sidewalks, and a couple of mounted police escorted us across the city. Our march was orderly. At the [fair]grounds, coffee and sandwiches had been prepared by a group of women volunteers, and after we had eaten, the Central Strike Committee met to plan their program of action.

We had to have a few days’ respite, to clean up, to rest. There would have to be some regrouping of our forces, many things had to be done...

It was a three-ring circus. Calgary had seen nothing like it before, and were pouring into the downtown area by the thousands.

This was reassuring to us, the more the merrier, or as we knew from past experience, the more the safer. Our job was to keep snake parading around and around the one block so that a continuous column was passing [City Hall]. We varied our singing with shouted slogans, “We want relief!” “Grant relief!” “Relief! Relief! Relief!”

Soon we had thousands of people joining in, and there would be a solid chant of “Relief!” repeated for a minute at a time. It was, though, some work for us, especially on empty stomachs. No traffic was moving. Downtown Calgary was tied up.

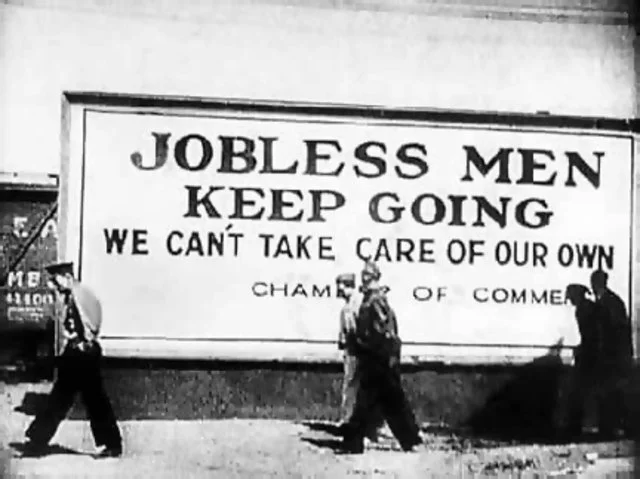

It isn’t surprising that cities such as Calgary were reluctant to feed the Trekkers. —Public Domain

[An hour of parading while a committee of Trekkers met with City Council to negotiate food vouchers was interrupted dramatically when] MacLeod, looking across at [City Hall] shouted out, “Oh, stop them, boys, they’re trying to get away!”

Everybody looked and, sure enough, coming out of the building was the [Police] Commissioner, the Mayor and one or two more men. As quick as lightning the leader of [Division Two], Comrade Thomas, moved on to the sidewalk, at the same time shouting, “First two people after me, the rest keep marching!”

Thomas made a rugby drive and brought the first man, the Commissioner, I think, down on the sidewalk while the men of Groups One and Two hustled the Mayor and the councillors back into the building.

MacLeod...helping the Commissioner to his feet, said, “Let us go inside and take up our talk where we left off.”

Our own Finance and Relief Committee were back in business again, and within an hour or so showed up at the Stadium with the meal tickets which were made out to certain cafes downtown. After everybody had eaten, squads of volunteers went to join in the Tag Day with the Calgary men and women who were really doing a splendid job on our behalf.

There is the possibility that we, the B.C. originals, had started to regard ourselves as being a wee bit exclusive. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that within the original family, that hard core of class conscious, politically conscious Relief Camp Workers of B.C., the Trek could have been overwhelmed and defeated in the great influx of crude, raw, unemployed recruits which joined us in Calgary.

The Recruiting Committee became all-important. A complex reorganization had to be accomplished. Groups were split into two and sometimes three sections, and then such sections would be rebuilt into full group strength by the addition of new recruits, so that the new groups would be composed of half newcomers and half Old Guard.

The newcomers had to be taught organization and discipline.

And there wasn’t enough time for a leisurely approach. We knew from experience that there would be attempts to disrupt our organization, in all probability an attempt sooner or later to smash us physically.

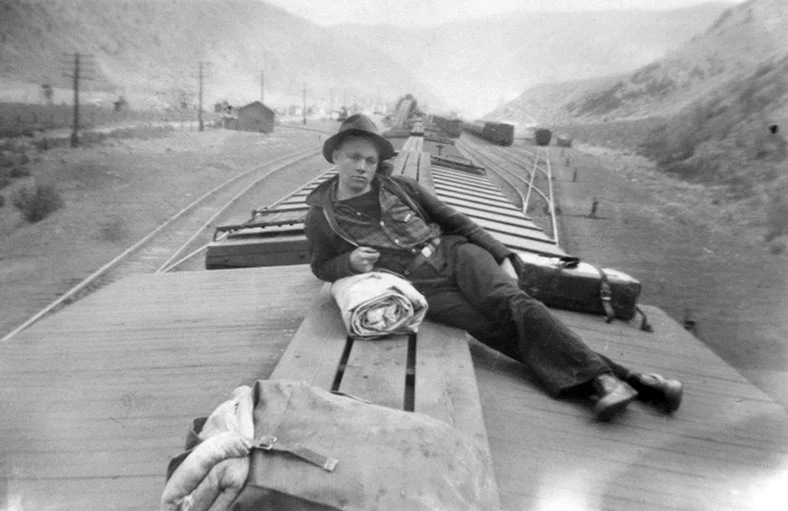

Like this lad, many of those who joined the Trekkers in Calgary were young and had to be quickly indoctrinated in the goals of the Trek and be taught discipline. —Public Domain

We had to convince the newcomers of the necessity to conform to our standards of discipline. Lectures were given on a Division and also Group level, outlining the history of our union, our past struggles, and our present objectives. The new members on the whole being unemployed youth, soon fitted in and became anew source of strength on the Trek.

We rolled into Regina about the middle of the month, that is, June 1935, and if there is any truth to this premonition business, then that is what of us must have felt, because every one of us thought that something different would happen here...

Our entry into Regina was something of a triumph. We had been successful up to now, had built our forces up. And we were a proud little army. As we marched through the city streets. Throngs of people lined the sidewalks to give us a rousing welcome. At the Exhibition Grounds where we were to stay as usual, an official welcome had been prepared for us.

In the huge building which we called as usual, the Stadium, there were gathered representatives of all the working people’s organizations, Communist, CCF, unemployed, trade unions, and there was a large choir from the Ukrainian Farmer’s People’s Temple Association. There were speeches of welcome and congratulation, and the choir sang for us. The Ukrainian organization offered us the use of their Labour Temple for as long as we were to be in Regina, and we held many of our camp committee meetings there.

There was lots of unemployment and poverty on the Prairies, and the people of Regina understood our struggle and made it their own. There was understanding and cordial relations between the camp workers and the people of Regina for the whole of the time that we were there.

Our marches and demonstrations had been blown up out of all proportion by the papers and news broadcasts and our strike parade was made to appear a magical formula before which civic authorities capitulated very quickly.

This was an exaggeration, of course, the strike parade had been devised by us in Vancouver as a defence measure. When we had seen, early in our struggles for relief, how easy it was for the police to barge into and by sheer force of weight and the club, to disperse a crowd on the street, we decided that we would not be dispersed as easily as that.

We found that, by linking arms, packing ourselves solidly together, taking up the whole of the street by weaving from one side to the other, we presented a more solid object. Add to this a loose revolving defence group on each side of the main body, these to engage the police and take the brunt of the first attacks, and it is true that we were hard to disperse, but always our best and sure defence were the masses of people that we could rally to the streets.

However, the press had made the snake parade notorious, and the people were disappointed if we did not respond, so that on the second day in Regina, we went through our paces on the downtown streets, and a good time was had by the thousands who thronged the streets, and by ourselves.

For the first two of three days in Regina everything was on a large scale. Our entry, our welcome, our demonstration, and finally, I believe on the third day, the whole complement of Dundurn Relief Camp, 500 men, marched in to Regina in a body to add their strength to the Trek. It was a stupendous event as the 500 men from Dundurn marched into the Exhibition grounds between the massed ranks of 2500 men of the Trek who were lined up to greet them.

We had intended to spend three or four days in Regina, to rest, to recoup our strength, do some reorganization, etc., and continue on our “On To Ottawa Trek”.

I think that was on the night that we held the big mass rally in the Stadium, to officially welcome into our ranks the men of Dundurn, that we received the double shock: the news from Vancouver of the “Battle of Ballantyne Pier” [see next paragraph] and the news that two cabinet ministers had arrived in Regina to parley with our strike committee and arrange conditions for negotiations with the prime minister of Canada...

[We] received the news from Vancouver [that locked-out longshoremen were dispersed by of armed and club-wielding City and Mounted] police with a feeling of intense frustration and regret. We all knew that had we been in Vancouver the police would not have dared pull a stunt like that. The Longshoremen of Vancouver were our friends and we would have fought to protect them at any hour of the day or night.

In 2020 the International Longshoremen and Warehouse Union Canada marked the 85th anniversary of the ‘Battle of Ballantyne Pier. —https://ilwu.ca/remembering-the-battle-of-ballantyne-pier/

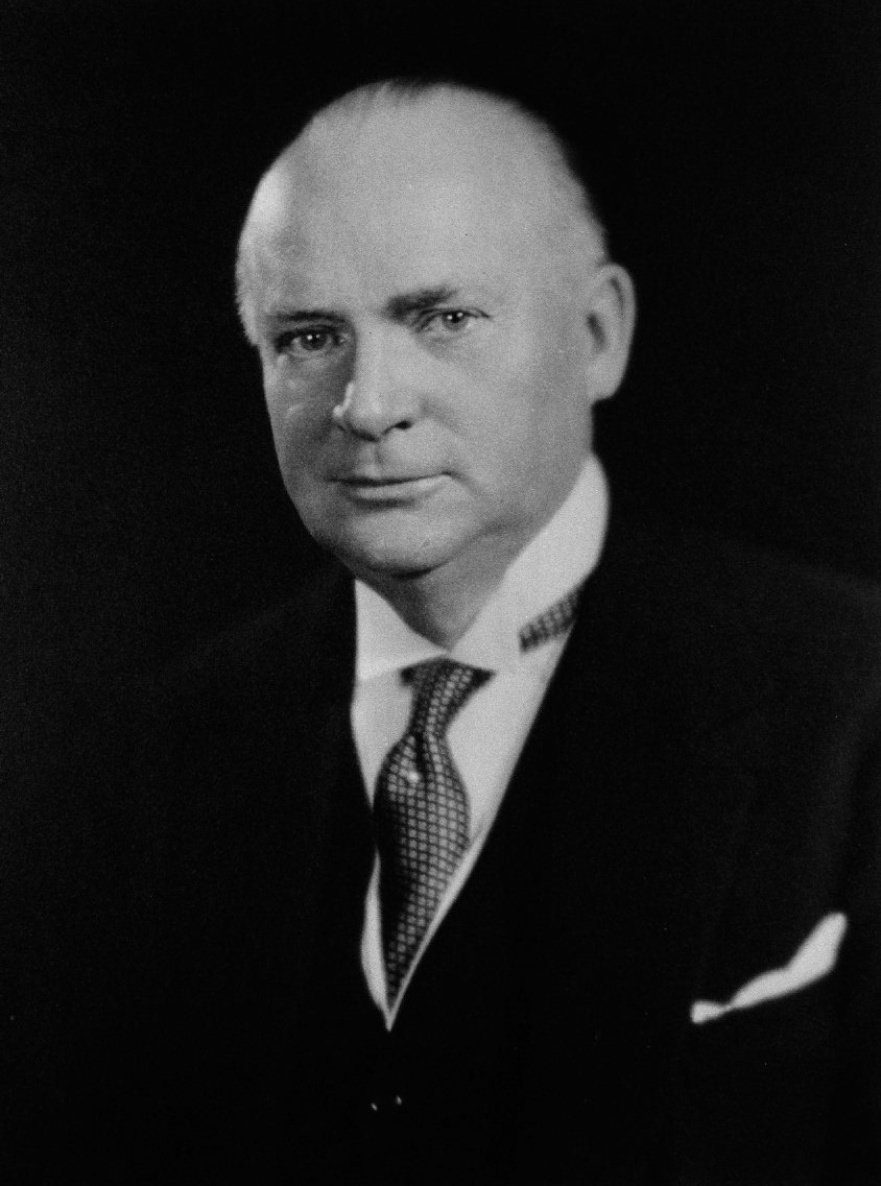

It was with this bitterness in our minds then, that we turned our attention to the fact that the great [Prime Minister R.B.] Bennett, the supreme ego of the 20th century, had been finally forced to take notice of us. The 3000 miles of isolationism between us and him had been considerably reduced, reduced by over one-third, and was likely to be reduced some more, so that we had to be finally taken into consideration.

The next day the meeting took place between the Strike Committee and the two cabinet ministers from the federal government.

Prime Minister R.B. Bennett. —Wikipedia

One of these gentlemen was the Minister of Education and was named the “Honourable Mr. Gray.” The other one’s position or name I do not remember, and apologize for my poor memory.

The two cabinet ministers were empowered to act for the prime minister. Their instructions, which were final and could not be changed, were that the prime minster would accept a delegation from the Trek, that the delegation would travel by train first-class, that from the time the delegation left Regina until it returned to Regina, the members of the Trek would receive at federal government expense, three meal tickets per day, and would give their pledged word to remain in Regina until the return of the delegation.

There was not one man of the more than 3000 Trekkers who did not recognize the manoeuvre of Mr. Bennett for what it was, a trap.

Even school children realized that the Prime Minister was incapable of making the proper gesture [by] offering to redress our wrongs. Every Canadian worker knew that in any dealings with the ordinary people of Canada, Mr. Bennett’s mind was incapable of rising above the double-cross. The federal government, which was in fact R.B. Bennett, needed time to gather police reinforcements at Regina, hence the belated offer to negotiate with the camp workers.

There can be no doubt whatever that we could have carried on with very little difficulty had we decided to reject Bennett’s offer. Our next big stopover would have been Winnipeg where 3000 single unemployed were waiting to merge their forces with ours on the journey to the east...

Despite all these considerations we had to accept the offer of negotiations.

For almost five years since the inception of the slave camps [in British Columbia] under the jurisdiction of the Federal Department of National Defence, our main demand, our number one slogan and the reason for our “On To Ottawa Trek” had been to negotiate our grievances with the federal government.

Now that we had won our demand, we could not turn the offer down. Had we done so, the newspapers of Canada would have made mincemeat of us. We would have been isolated from our only support, the support of the Canadian people.

* * * * *

As we shall in next week’s conclusion to the saga of the On-To-Ottawa Trek, Prime Minister Bennett had no intention of letting the Vancouver Relief Camp Workers, now reinforced with Alberta’s unemployed, join ranks with Winnipeg’s 3000 relief workers—let alone go on to Ottawa.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.