Pioneer Days in the Cowichan Valley (Conclusion)

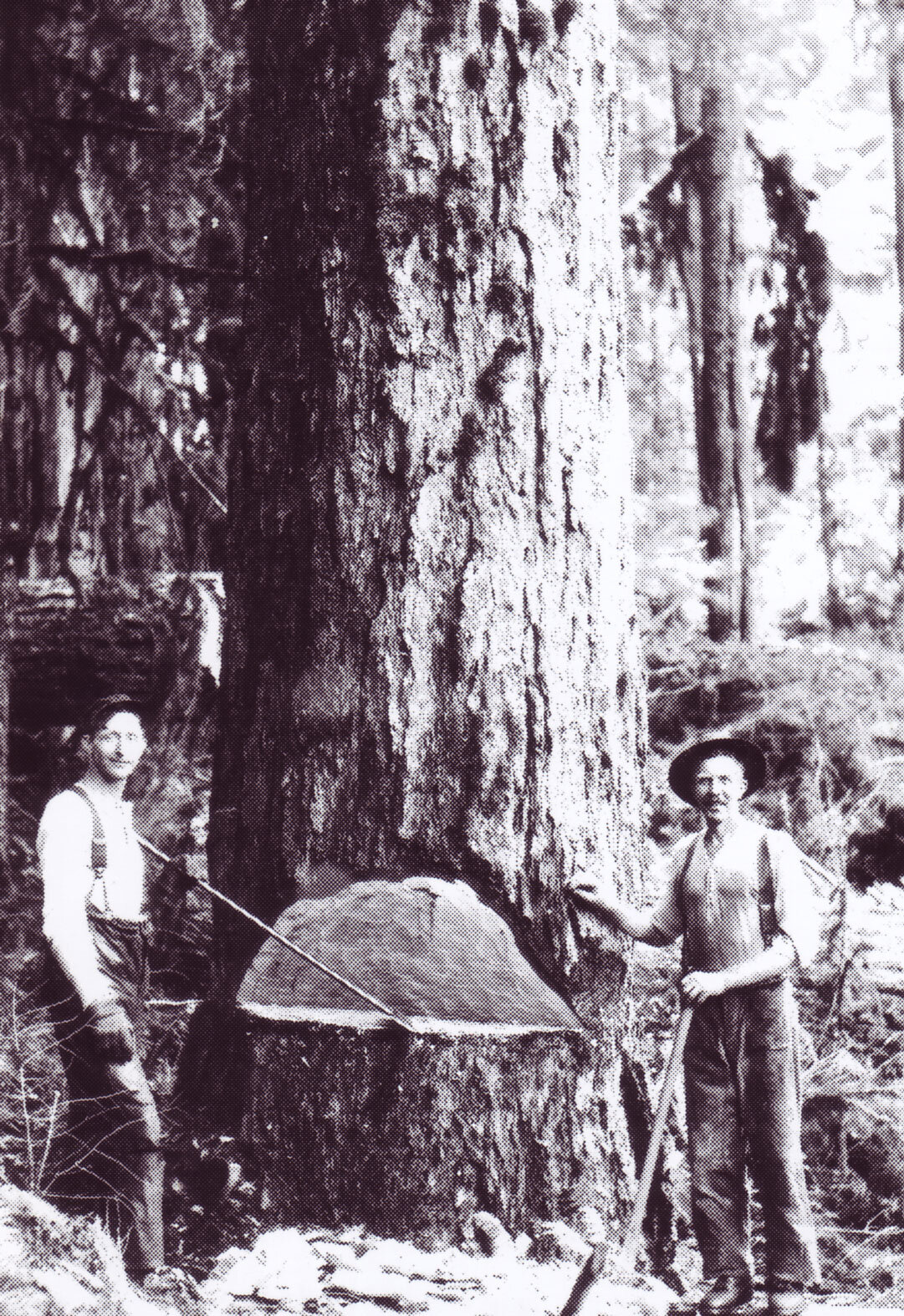

As our pioneer historian describes so well, THIS is the way they cleared the land in the Cowichan Valley, with hand tools and muscles. Something to think about as we drive by the acres and acres of green fields in Cobble Hill, Westholme, etc.

This is the third and final instalment of an unidentified pioneer’s recollections of Cowichan Valley pioneers, most of whom he’d known personally, and of the dramatic changes he’d witnessed over his own lifetime.

To maintain its original flavour, I’ve kept editing to an almost non-existent minimum. To correct the misspellings and grammatical errors would take away much of its charm. Hence I’ve only interceded when I felt absolutely compelled to do so to maintain clarity.

* * * * *

But we cleared land, and that is what most of you are intrested in. To me there is not more intresting work under the sun than clearing land when the land is your own. We went at it whole heartedly in those days when work was the joy of life.

Now in those days you must remember we had no blasting powder or any modern machinery to help us, we put our trust in an axe, a brushhook, a mattock, a shovel, a canthook and a saw and found them sufficant. First of all we would select a piece of bottom land or swamp where alder and willow and crabapple grew, for the reason that generally speaking that was the richest available land and also because the stumps of that class of timber would rot in from three to five years. So they could be grubbed out very easily. Of this kind of clearing a man could do from three to five acres a year at first, slowing up as every acre cleared added to his work in cropping it.

First we would slash it, piling very carefully to ensure a good burn, and as there were no fire wardens of fire restrictions in those days we generally got it to burn and frequently had to do some tall fire fighting as a consequence. There isn’t anything you can tell us old settlers abut fire danger and fire precaution, we have all been through the mill and had our experience[s]. And it is no joke to stand by and see the labour of weeks, months or even years swept away before your eyes in a few minutes. Nor is it any joke in the dog days of August to be tugging away at the end of a fence rail with the fire crackling at the other end of it. There were the times [too] when a neighbour at hand was better than a friend afar as Solomon put it. In these emergencies you could count on every neighbour night or day to stand by you, without money and without price.

Generally the loss if any was in the shape of a fence, a bush fire in a snake fence makes merry headway. One old settler at Sahtlam could tell you how he stood up to his waist in snow one winter, sawing a huge tree about six feet through into stove wood and after his hard toil he went about hugging himself with the thought of enough beautiful firewood to last two winters. But alas for anticipation, next summer a smoldering fire he had left, started afresh in his absence and swept the whole pile out of existence. That borders on tragedy.

But the eliment of comedy creeps in sometimes as well.

In the case of old Lewis, a Welshman and one of the characters of early days, Bill Brown used to tell in his unmistakable Irish way how he met old Lewis one scorching day in July going down into the meadow bottom where his hay was all standing in the cock crackling dry. At the end of the hay was a small slashing, crackling dry too. “When are you going to haul in that hay, Lewis?” growled Brown. “Oh, I think I’ll just set fire to that bit of slashing first.” “Well, your a fool if you set fire today, you’ll lose all your hay.”

“What do you know about fire?” snarled the old man, “You can’t tell me anything, I’ve fired on occasion,” and he stamped off in a rage. While Bill called after him, “Well, if you strike a match today you’ll have to fight fire in Somenos,” and went on with his work. In about fifteen minutes he heard an awful yelling over in the next bottom and ran to the top of the ridge in time to see old Lewis running like mad and bawling for help as he barely beat the fire which was crackling at his heels in getting out of that bottom. We are sorry the old man lost his hay, but he gained in experience.

We seem to have got off the track here and will have to hark back a little. After a good burn which left only a few butt ends and small logs, these were picked up and piled. When the ashes were cold the burn was seeded down in clover and thimothy. With thick seeding and any luck as to weather, a fine catch resulted. You could either mow around the stumps or pasture cows on it. In about three years most of the stumps could be kicked out and the plowing and breaking up was an easy matter. That was our class of clearing and the easiest and quickest.

When we tackled the big timber it was a more serious problem. The first thing of course was to fall the trees. In the very early days that was all done with the axe, later saws were used and found easier and quicker. Falling the timber was the easiest and most pleasant of the operation, it was a wise thing in falling to lop all the branches to ensure a clean burn. Then the logs were sawn into lengths about four feet for logging it. This cutting up required a good deal of skill and judgement to get resaults, and in piling the logs. A working unit of three good men and a team was the most effective. We used to have logging bees to, where large parties gathered and made the work more light and intresting, but the usual way was for two or three neighbours to work together and exchange work. It was surprising the quantity of logs three good men could pile up in a ten hour day with out hurting themselves.

After logging...the stumps were left and believe me they were sometimes enough to stagger anyone but an old settler.

There were three ways you could tackle them. If you didn’t mind mowing or ploughing and working around them, you just left them where they were. Another way was to burn the top of the stump level with or a few inches below the surface and leave the roots alone, in this way you could work over a level surface but it was tough on the man who had to do the ploughing afterwards. The other way was to dig them out, and before the days of stumping powder, you can imagine what that meant. I have always believed that life was to short to spend it in that way, even while doing it, for we have grubbed and helped out a good many in our day.

I have sometimes thought if I were an artist I should like to paint a picture of one of these five foot diameter stumps half grubbed out with all the paraphanalia scattered around it, shovels, mattocks, axes, crowbars, canthooks, saws, wedges, hammers, lines block and tackle and logging chains.

With a dejected looking team of horses standing by and two tired looking old timers in the foreground surveying their labours. Roughly that is how we cleared land in the early days. Hard work.. Healthy work, interesting work, to see your clearing bite deeper into the forest year by year and to know that by that way lay the road to independence.

But no millionaire was ever made in that way, we have thought that the whole ethics of land clearing was apply summed up in the remark of a lady long ago when we stood on the road overlooking Somenos swamp. I pointed out to her all we hoped and planned to do in reclaiming that swamp and how there was a fortune in it for some body. After I was done she turned and said quietly, “What a lot you boys are planning to do for the next generation.” We let it stand at that. The swamp is not all cleared yet, no one of us has realized the high hopes of our youth. But “no one liveth to hiself.” There is not one of these old timers but has left his mark on the progress of our district and done everything for the generations that shall follow.

The houses were built of logs in those days and many of them are still standing yet. One built by Mr. J. [Evans] stands today in the heart of Duncan, an object of great intrest.

There was no particular acquisition [sic] to size or shape, it depended on the individuals taste or the size of their family. One man is on record of building so small that if he wanted to turn around he had to go out side to turn. Another man built his so large that he never did finish it. We didn’t worry much about windows, you would call them dark and ill lighted today. But they were warm and comfortable, when chinked with moss and clay and served there purpose.

The fireplaces we used to build into these sometimes were made of loose rocks and plastered with clay. I recall our first log house built in this way, the finest drawing fireplace I ever saw. The chimney was so low and wide our old cat used to make it her way of going in and out, until one winter night when we had a roaring fire going and a neighbours dog came in by the door, the cat promptly left by her usual way and left an awful smell of singed fur behind. She wasn’t seen for a week and on her return we noticed she always used the door after that.

This method of building fireplaces however had its disadvantages. It was all right so long as you had a fire on every day and kept it dry. But after a week[’s] absence in the rainy season you would find your chimney lying inside your fireplace on your return. Which made a bad preparation for the sabbath. Barns were built of logs to and many a merry logrolling we had putting them up, but they were satisfactory, the only recommendation they had was they required no boarding up. Stout cedar posts set in the ground, with strong plates, ties and rafters have been proved as best and most practic[al].

One mistake was made before we got wisdom of experience was in framing to[o] light timbers and insufficent bracing. We could only guess at the strain to which they would be subjected and in summer when they were generally built the temptation to put in the lightest possible timbers was great. But in the winter of 1886 after a heavy fall of snow followed by a soaking rain many an old settler cast anxious eyes at the bending rafters and bulging walls. A good many collapsed barns resaulted. Luckily with little loss of stock. The most notable case was that of John Shopland at Maple Bay and the marvellous escape of his stock.

We had a gay time stamping and slushing around in the snow clearing away the ruins and building temporary shelters for his animals.

All this was voluntary labour by neighbours far and wide. Perhaps I could point this out as a concrete instance of the neighbourly help we gave each other in times of need. Barn raising bees were plentiful and always the occasion for great social emenity. A good deal of stimulant was sometimes needed and bountiful provisions of things to eat. There was generally a good deal of confusion and a great many bosses on the job, but always without fail we got the barn raised.

Gradually a better class of house and buildings was evolved, we even began to put a little paint on them.

Frame houses, hand finished, panel[led] and decorated with all modern conveniences have been built since then. Beautiful homes that our district is proud of. But these do not belong to old times. And they will never have the halo of old romantic intrest that attaches to the humble log shanty.

I intend to say something abut the old time politics though perhaps it is hardly safe to mention here to night, but I am not going to say a word that will disturb the amenity of this evening. They took their politics seriously...those old timers and they took them as some of them took their whisky, strait, going back a long ways to the time when there was no secret ballot, a voter had to call out to a returning officer the name of the candidate he voted for, and back to the days when there was no law forbidding men to shout within a mile of the polling station on election day or to carry a flag or bear colors. Some of the old timers were very fond of trying how close they could run their vote to closing time and would try to work up a little sensation by just beating the clock. One election old Jim Boal did succeed in bringing it off. When J.P. Booth of Saltspring Island was returned as one of our members; we had two in those days.

All the votes were in and they stood at a tie, everything depending on the casting vote of the returning officer. All eyes had been on the clock and on the road alternately to see if no other voter would show up to turn the scale. At last it came ten minutes to the hour and nothing doing. Then 8-7-6-5 and all hope was abandoned but at 4 minutes a horse was heard away up the road, pounding down the hill to the polling station, lickety split, the old man threw himself off, stuck his head in at the door and bawled, “I vote for Booth.” As the clock struck the vote was allowed and Booth was elected and Boal was the hero of the hour. But we would not advise any voter to play that trick next Wednesday on the chance of a repeat.

We had no party politics in those days and I doubt if we got any better government on that account. Broadly speaking we believed in our democratic institutions that the man elected would represent those who elected them no matter what they may call them selves.

We have no need to be ashamed of the men or their record who represented Cowichan in those early days. Our own district of Somenos has given three Premiers to the province. We note too that Somenos has generally given a Reeve to the municipality. It is curious how all the old arguments and election cries and issues of those days have been forgotten, while little incidents of the campains stand out clear in our memories.

Like the time when Theodore Davi[e] and Henry Croft were holding an election meeting at the old Somenos school house. They were both very convivial spirits, and quite understanding, how a great deal of liquid argument was required in that day to carry an election. A good stock of course was carried in the buggy they travelled around in, but on this night they figured to put up an over whelming argument [so] a whole keg of beer was ordered up from Duncan.

Our little post man, Joseph Kier, under took to deliver both the goods and the candidates to the school house.

Any old timer will recall how Joe use[d] to drive when he got a little bit excited. So it happened they started out a little late for the meeting, with the beer and the candidates on board his two wheel rig. Joe under took to make up time, you’ll remember our roads were not so good then as now, coming up the hill from Duncan the tail door fell down and the keg bumped out and rolled over the bank. It was found there the next morning, but there was great consternation when they arrived at the meeting with no argument to put up. I don’t know that it influenced the election. Both candidates were returned. But it furnished us with a good joke and is the one thing about that election which remains when all else is forgotten.

I am going to stop here while you are all in a good humour. The things I have told you about the old timers and the old times, we fear have been very disjointed and scrappy. No one can do them justice in an hour of speaking but I hope some one some day will feel inspired to set down and write a book which will to some extent enshrine there labours and keep there memories green.

* * * * *

Well, there you have it, one pioneer’s colourful look back at his immediate predecessors, the first generation of “old timers” whom he so obviously admired and respected.

I noted at the beginning that I’m not sure of our author’s identity but upon reading and re-reading this several times, I finally spotted the giveaway clue: he was secretary of the Agricultural Society in 1911!

Now I have something to pursue. Consider it a work in progress until I can get back to you.—TW.