Pioneer Methodist Cemetery

Our current pandemic may be a burden to us humans but, apparently, it’s been a blessing for some flora.

A resident who lives near Maple Bay’s historic Pioneer Cemetery, just off Herd Road and so tucked away in the trees as to be invisible and all but unknown to passersby, recently complained to North Cowichan Council that the vegetation between the headstones had gotten out of hand.

The Municipality responded immediately and explained that COVID-19 has also played havoc with its work schedules hence the cemetery’s temporary neglect.

I wonder how many Chronicles readers even know of the Pioneer Cemetery’s existence let alone have been there. I can assure you it’s well worth a visit and it really does call to mind the expression, “God's Acre."

* * * * *

Pioneer Methodist Cemetery - Herd Road

Long before there was an E&N Railway or the Island Highway over the Malahat, Maple and Cowichan Bays served as the gateways to the Cowichan Valley. Hence Maple Bay was a likely site for a Methodist church. Previously, Methodists had shared the Anglican chapel at Somenos, their minister attending from Victoria. In 1868 they held the first of three annual outdoor meetings at the site of today’s Maple Bay Inn. The Saanich-milled lumber from the ‘tents’ used for those occasions was recycled the following year in construction of a modest log church on 100 acres pre-empted by the Rev. E. White.

Missionary Thomas Crosby tells of the Methodists’ first efforts at Maple Bay in his book, Among the Ankomenums of the Pacific Coast: “Camp meeting have been among the most successful means of reaching the Indians and bringing them to the light. In June of 1869, the first camp meeting ever held in B.C. [sic] took place on what afterwards became historic ground at Maple Bay. Lumber had been brought from Saanich mills with which to build a church, and this lumber was used to make ‘tents’ for this first meeting. The steamer Enterprise brought people from Victoria and New Westminster. Indians from Chilliwack and Sumas as well as from Nanaimo, gathered in large numbers. Following the meeting we had a mighty spiritual upheaval at Nanaimo which gave us great encouragement. The second camp meeting [sic] at Maple Bay took place in July 1870, and in September of the same year....”

Another source tells us that the Rev. White, “ably assisted by his lieutenant, Brother Crosby,” conducted the tent meetings of 1869 and 1870 under unspecified “circumstances of difficulty and discouragement”. But they prevailed and “many decided for Christ, especially young people, and some backsliders were restored. The Indian services under Brother Crosby’s direction resulted in many conversions, and wanderers from their Father’s house were brought back with shouts of rejoicing.”

Erected by volunteer labour and lined with tongue-and-groove lumber, the little church served intermittently for 24 years. Unfortunately, as United Church historian G.W. Owens has noted, few records were kept of those years. It is known that the Revs. Derrick and Bryant, both of Nanaimo, took the services every other fortnight for several years and the first minutes of the trustee book were entered June 24, 1875. After the Rev. W.V. Sexsmith’s departure the church reverted to monthly services then, from 1881 to 1883, stopped altogether until a visiting minister could again attend on a monthly basis. Thus it seems somewhat surprising that the corner-stone for a second church, in place of the first, which likely had outlived its usefulness, was laid, on the far side of Herd Road, on October 10, 1893. Sale of 50 of the parsonage’s acres financed this second church which cost $602.40. The balance of the excess acreage, with the exception of the cemetery and its roadway access, was sold in 1904.

The years passed and times changed and, after 61 years of service, this, the second Maple Bay Methodist Church was closed. It is now a private home.

There is no sign of the first church now, just its small graveyard and a plaque, installed by the Native Sons of B.C., Prevost Post No. 10, identifying the site. Responsibility for the cemetery has been assumed by North Cowichan Municipality.

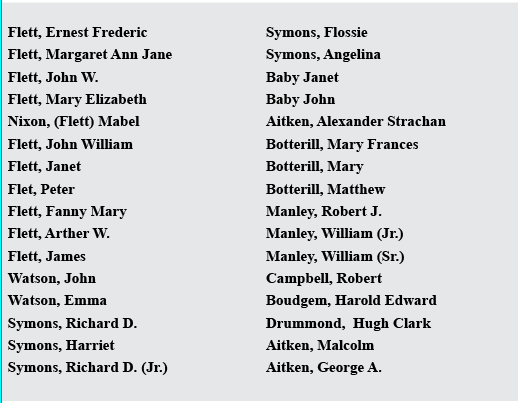

CEMETERY

Tucked between trees and farms, Cowichan’s Pioneer (Methodist) Cemetery is out of sight and out of mind but for those, it seems, who use its secluded driveway for purposes of their own. Some of our earliest pioneers, the Manley’s, the Fletts, the Aitkens and others, take their rest here, at the end of appropriately named Pioneer Road. For that matter, it always will be a ‘Pioneer’ Cemetery as, by North Cowichan bylaw, “Only those persons and their spouses residing in the Cowichan Valley prior to 1900, and their direct blood descendants and spouses, may be interred [here].”

The winding lane from Herd Road leads to an unlocked gate. Immediately inside, a brass plaque on stone and concrete tells us that the “first Methodist church in Cowichan stood a few feet away” and the first burial took place in 1870.

With its emerald-green grass, red, white and pink button-top field daisies, and the pleasing droning of bees all but overpowering the faint background of passing traffic, Pioneer Cemetery is as peaceful on a sunny Spring afternoon for the living as it is for the dead. At least half of the cemetery remains unused with some wide spaces between plots. On the left and closest to the gate are the only graves on this side.

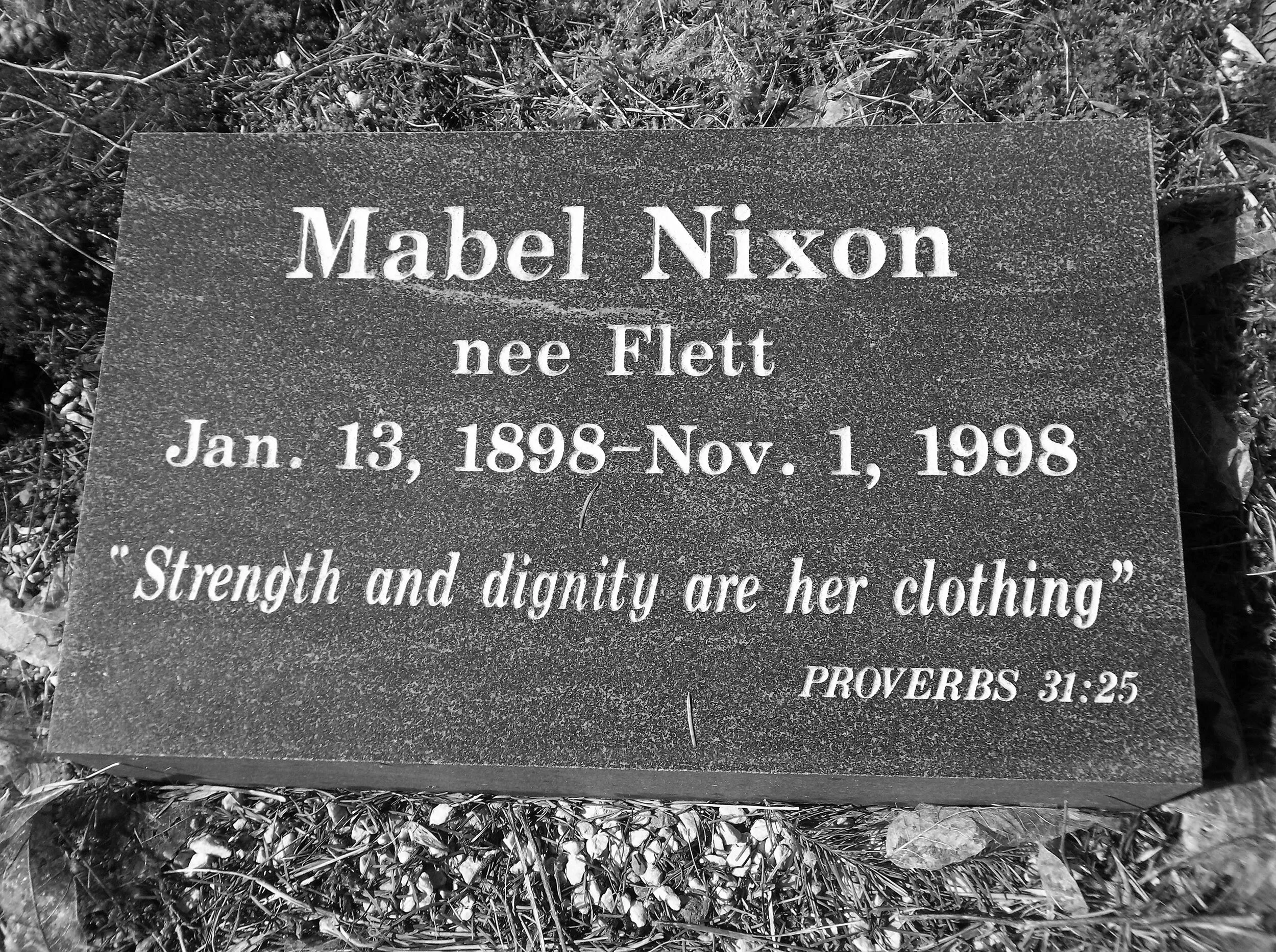

Four cornerstones of granite identify a large family plot but the single headstone is that of Ernest Frederic Flett, 1905-1987, and Margaret Ann Jane Flett, 1913-2002. They are across from John W. Flett, 1855-1938, and Mary E. Flett, 1873-1971, and their daughter Mabel (Flett) Nixon, January 13, 1898-November 1, 1998. Mabel is the only one here who made it to her centenary and her headstone indicates she is the most recent interment. When, in January 1988, more than 100 relatives and friends joined to celebrate her 90th birthday at Duncan United Church to, she recalled that Maple Bay “was a wonderful place to grow, even though in those days, there weren’t many things a woman was allowed to do, except stay home with her parents. But I did manage to do a bit of personal nursing” before marrying John James Nixon in December 1941. She was the first bride in the new Duncan United Church. As the wife of a Methodist minister, she accompanied him to Nanaimo and Cumberland. A year after they returned to the Duncan United Church parish in 1946, John died of cancer. For 30 years she ran a boarding house. By her 80th birthday, she appreciated living on her own again with three cats, birds and a visiting seagull. While living in Duncan, “her pew” was the one her mother had occupied before her. At the time of her passing she resided with family in Mission.

Her father, John William Flett served on North Cowichan Council and as a school trustee and was active in the historical and agricultural societies, faithfully attending every Fall Fair from 1870 to 1937. There is an intriguing footnote attached to John W.’s 1938 obituary: “It is some five years since a burial took place in the Maple Bay Church cemetery. The first burial ever held in that cemetery took place on the day that Mr. Flett arrived in this district, March 5, 1876. On this occasion a white man [who was] shot by Indians who mistook him for someone else, was buried.” This date, obviously, is at variance with the memorial plaque.

A close-up of Mabel (Flett) Nixon’s headstone.

In an interview for a Victoria newspaper, probably in 1968 as it mentions her approaching her 95th birthday, Mary Elizabeth Flett was said to be one of the few people still living who could recall the big day the first Esquimalt and Nanaimo train steamed into Duncan with Sir John A. Macdonald and “a group of major and minor celebrities aboard...”

“They sure were surprised to find such a big crowd waiting for them,” she said. “Especially since it was almost decided that the railway station was going to be located at Somenos. The only reason they built the station on W.C. Duncan’s farm was because the farmer at Somenos wanted more money for his land [sic]. Every available person, white and Indian–must have been 2000 or more–was there that day.”

Her vivid recall did not surprise her interviewer who found her to be bright-eyed and clear-headed, with a handshake “that would put a longshoreman to shame”. That, at a time when she was hospitalized with a broken hip and the ‘flu! (It was only her second trip to a hospital in 95 years.) One of the many Cowichan Evans clan, the daughter of John Newell Evans, she was born in California because her mother had turned back after Indians attacked the wagon train in which she was crossing the American plains and killed many people. By the time they arrived in Cowichan, Mary was almost five. She recalled being ferried across the Cowichan River daily to go to school as there were no bridges, going to the fall fair at Maple Bay in an oxen-drawn wagon, acting as nurse while a doctor removed son Alfred’s tonsils on the kitchen table, and meeting face-to-face with a bear. “We looked at each for a while. Then he went, and I went–different ways.” She married John W. Flett in October 1893 and had three children, Arnold Christmas, John Alfred and Mabel. She concluded her interview on a nostalgic note: “Sure, we worked hard in the early days [but] people in the Valley all seemed like one big family. We all helped each other.”

At the time of her death, nine days short of her 98th birthday, she was one of Cowichan’s oldest pioneers.

Observe the striking cross-and-crown logo on the headstone of neighbouring Janet Flett, January 1, 1823-June 7, 1909. At that time, The Cowichan Leader reported, “Another gap was made in the ranks of the pioneers of the Cowichan Valley when the death occurred on Monday last of Mrs. Flett [sic], widow of the late John Flett and the residence of her son, at Maple Bay. The deceased, who was 86 years of age at the time of her death, came to this district 55 years ago.” Among her pallbearers were John Watson and R.D. Symons, who have since followed her to Pioneer Cemetery.

The Cross and Crown logo on Janett Flett’s head stone can be seen frequently in other Cowichan Valley cemeteries.

Peter Flett, November 26, 1861-December 30, 1919, who lies with wife Fanny Mary Flett, September 9, 1870-May 23, 1940, had been in failing health for the last two years of his life. A farmer like his parents, he was said to be “of a retiring disposition [who] did not enter much into public life” other than his involvement with the Methodist Church. Widow Fanny was an active church woman, Sunday School teacher and member of the Women’s Auxiliary.

The youngest of this pioneering family is Arthur W. Flett, who died at the young age of 24, in October 1915. Born at Somenos, his father had for a time been the stationmaster. An exception to the Flett preference for the Maple Bay Cemetery is James Flett, who was thought to be “Vancouver Island’s oldest native son” at the time of his interment in Mountain View Cemetery in May 1948.

In 1991, Alfred Flett, then an alderman in Nanaimo, recalled how Grandfather John Flett arrived in Nanaimo from the Orkney Islands in 1849. A cooper, or barrel maker, by trade, he accompanied the first miners imported by the Hudson’s Bay Co. to work in the Fort Rupert coal mine and was working in the San Juan Islands at the time of the famous ‘Pig War.’ After a stint as a fur trader he began farming at Maple Bay. Another family history tells us that John worked for the HBCo. for 20 years, returning to the Old Country at the end of his first five-year contract to marry his first cousin Janet; he was 27, she was 33. When they reached Victoria, April 1, 1855, it was John’s third rounding of Cape Horn under sail. For Janet, it had been even more daunting as she was pregnant; she gave birth to John William Jr., four months after their arrival. John Sr. continued in the employment of the fur company, in Victoria and on San Juan Island, as a cooper and as a fur-grader until, aged 42, he traded his house in Victoria for a house and pre-emptive rights to100 acres of Crown land at Maple Bay. Before long, he acquired a grant for a further 50 acres.

Continuing the senior Fletts’ story by descendant Victor E. Jaynes: “With their four sons ranging in age from [fourteen] down to eight, John and Janet arrived by ship at Maple Bay on 5 March 1870. A large cart and two oxen were borrowed to move their possessions to the farm over a rough road. When one of the cart’s wheels gave way a tree was felled and from it a makeshift wheel was cut and fitted. Any pleasure they might have felt on entering their new home would have been dampened by news on arrival of the burial of a nearby settler, murdered it was suspected, by an Indian...

“John’s decision to settle at Maple Bay owes much if not all to the precedent set by his younger brother James who some three years earlier had commenced farming a 100-acre block adjoining John’s new farm. This too was Crown land for which James obtained the freehold on 21 June 1871, having paid 100 [pounds], probably in instalments of 25 [pounds] a year. James had left Stromness at some time after 1851 and was on the west coast in time to take part in the Cariboo gold rush of 1858... There is nothing to suggest James was one of the lucky few. Late in life he became the fourth husband of Charlotte Jane (Lottie) Reeves. There were no children of the marriage, a circumstance which helps explain why so little is known about James’ life story. [James is in Mountain View Cemetery.]”

John, who helped to build the Maple Bay church and who served a term on North Cowichan Council, died, aged 58, after an injury to his left foot became infected. By the time he reached medical assistance in Victoria, his gangrenous leg had to be amputated and he succumbed, February 4, 1886.

Keeping company with the Fletts are in-laws John Watson, 1843-1910, who “fought a good fight...finished [his] course [and] kept the faith,” and his wife Emma Watson, Feb. 10, 1840-February 17, 1912.

Right of centre are three headstones, side by side, for Richard D. Symons, June 20, 1827-February 18, 1883 and wife Harriet Symons, May 3, 1828-September 21, 1915, who “died at Duncans, B.C.” (Note the plural in Duncans; today’s Duncan, singular, has evolved from Alderlea, Duncan’s Crossing and Duncans to Duncan.) A single headstone lists son and namesake Richard D. Symons, 1857-1912, wife Flossie Symons, 1894-1949, and daughter Angelina Symons, 1903-1939.

Between the Aitkens and the Fletts, a distinctive rough granite headstone marks the graves of Baby Janet, 1901, and Baby John, 1907. Even more striking is the pinkish-orange heart for Alexander Strachan Aitken, 1919-1931.

So simple, so to the point: ‘Baby Janet,’ ‘Baby John.’

The most eye-catching grave here is the heart-shaped head stone for Alexander Strachan Aitken, 1919-1931.

Mary Frances Botterill, the third daughter of Matt. and Mary Botterill, was just 17 years and four months at the time of her passing, April 10th, 1885. Her headstone, mid-cemetery, intrigues visitors with its poignant epitaph:

A light from our household has gone

A voice we loved is still;

A place is vacant in our home

That can never be filled.

Parents Mary Botterill, who died June 5, 1903, and Matthew Botterill, a native of Westow, Yorkshire, England, who died April 18, 1921, are beneath the red column: We loved you most who loved you best. You can barely read the inscription on William Manley’s concrete tombstone which, with that of son Robert J. Manley, 1868-1959, is almost mid-cemetery. William Jr. and twin brother Robert are thought to be the first white children born in the Cowichan Valley. Fortunately for Robert, his headstone is of bronze.

William Manley (Sr.) inspired the naming of Cobble Hill’s Manley Creek. No more than half a mile long, it flows northeasterly into Satellite Channel, between Hatch and Cherry Points.

Although one of Cowichan’s earliest settlers, this Irishman was not the first to settle there, the 200 acres he pre-empted in the early 1860s upon his arrival from the Australian gold fields having originally been claimed by Alphonse Verdier in 1858. Manley’s farm consisted of large meadows and forest, all fed by natural springs on its western side, hence the name ‘Springvale.’

The late historian Nathan Dougan credited William Manley with being the first to practise “practical agriculture” in the southern Cowichan Valley. He was, to again quote Dougan, indefatigable. Not that he, nor any other settler, had much choice; it was brawn against bush with no quarter asked and none given.

After building a solid house, Manley had to make his own roads, too, starting with a trail to the beach, that he might row to Cowichan Bay to meet the coastal steamships. This was essential to him when he produced his first crop of vegetables, the surplus having to go to Victoria for sale or trade. But he also needed an inland route. There was no railway, no Island Highway over the Malahat, not even a wagon road, just game and Indian trails that followed the line of least resistance via Shawnigan Lake and Sooke, and known as the Goldstream Trail.

Manley went to Victoria, likely by boat, to take delivery of several head of cattle he had ordered from Oregon and began driving them home in a windstorm. When a toppling tree struck and killed one of his cows, it was back to Victoria to order a replacement. This time he made it home with the nucleus of his future herd.

Despite such a daunting schedule he found time for civic affairs, helping to build the South End’s first school in 1869, and to go courting. Robert Hopkins (like Manley, like the many Dougans, also of the ‘Auld Sod’) and sister Margaret had settled at Cobble Hill. The three became friends if not really neighbours, Hopkins cutting a trail to Telegraph Road so they could exchange visits with Manley. Originally Hopkins’ Swamp Road, according to Adelaide Ellis’s history of Cobble Hill, today its southern end is Lover’s Lane. In honour of William Manley and Margaret Hopkins?

They were married at St. Paul’s Garrison Church, Esquimalt, in 1867. The following June, Margaret gave birth to William Jr. and Robert, reputedly the first white settlers born in Cowichan (Dougan) or the first white twins born in the district (Ellis). Margaret Jane followed two years later.

William Manley did not long enjoy the fruits of his labours, dying in 1873 of a kidney ailment. He was only 48. Neighbours rallied to help see him formally interred in the Maple Bay cemetery. A crude coffin was made and loaded aboard an ox-drawn cart for the ride to the beach, where it was transferred to a rowboat for the pull to Cowichan Bay. There, it was again loaded into an ox-cart for the final leg of William Manley’s earthly voyage.

With help, Margaret Manley continued to manage the farm. One day a cow grazed her across the face with its horn. Daughter in her arms, the twins a-tow, she staggered through the woods to the Rogers’ homestead on the ridge overlooking Dougan Lake (by today’s Valleyview Centre), where she received first aid before proceeding to Victoria for proper medical attention. She survived, to move to Cowichan Flats with her new husband, James Boal. She died in 1893. For almost 20 years she had been friend, mother and nurse to one and all. Father Rondeault, founder of the Butter/Old Stone Church, called her “an angel of mercy.”

The Watson marker stands out among the head stones in Pioneer Cemetery.

William’s and Robert’s graves stand apart from the others but for immediate neighbour Robert Campbell, who was from the County of Antrim, Ireland, and 43 years old when he died in 1876. Beyond two trees towards the back of the cemetery, is another child’s grave, that of Harold Edward Boudgem, who was called to rest, August 15, 1898, aged five years and three months.

The conspicuous red stone for Hugh Clark Drummond, who died, aged 41, October 10, 1926, denotes a family plot yet he appears to be alone. A smaller red granite marker, for Malcolm Aitken, 1916 - 1994, bears the appropriate, “At rest among the pioneers.” The four almost identical granite headstones for members of the Aitkens family invite the question, why is that of George A. Aitken, 1908-1948, only half-size? Sub-sized headstones usually mark the grave of a child, hardly the case of 40-year-old George.

Certainly Cowichan’s first settlers earned their rest. Pioneer Cemetery’s idyllic setting in the trees off Herd Road seems most fitting.

(From Tales the Tombstones Tell: A Walking Guide to Cemeteries in the Cowichan Valley, T.W. Paterson, FirGrove Publishing, 2012)

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.