Re-dedication of Memorial Recalled 1886 Harbour Tragedy

It happened in an instant, with a single flash of flame like that of a lightning bolt.

* * * * *

We know that more than 600 miners were killed on the job in Nanaimo area coal mines over that industry's 80-year history. If we take into account those who died later, sometimes much later, from their injuries or from work-related illnesses, the death toll must be much greater.

Nor is it likely that either of these totals include the six longshoremen who were killed in a blast of ignited coal dust while loading the steamship Queen of the Pacific at Cameron Island, July 29, 1886.

The Nanaimo coal jetty about the time of the horrendous accident of July 1886. —BC Archives

According to the headlines in the Nanaimo Free Press, 12 men had been severely burned and several others “slightly scorched” while loading the Pacific. The tragedy began with the cry of “Fire!” followed almost instantaneously by an explosion between decks, and “the outburst of an immense sheet of flame through the forward hatch”.

Of the 20 men who were working below decks, trimming the coal, 12 received severe burns about the head, back, chest and arms. Some of them, panicking or in agony, jumped overboard and, upon being picked up by the ship's crew, were rushed to the infirmary of Dr. D. Cluness, medical officer for the Marine Department. There, he and Doctors. Renwick and Davis partially dressed their injuries while Dr. O'Brien attended to those still on board the ship.

All the while, teams of horses and wagons were being rounded up to serve as ambulances to take the injured men to the city hospital. The newspaper described it as “a pitiable sight to see the poor fellows with the burnt flesh hanging to their arms, hands and faces”.

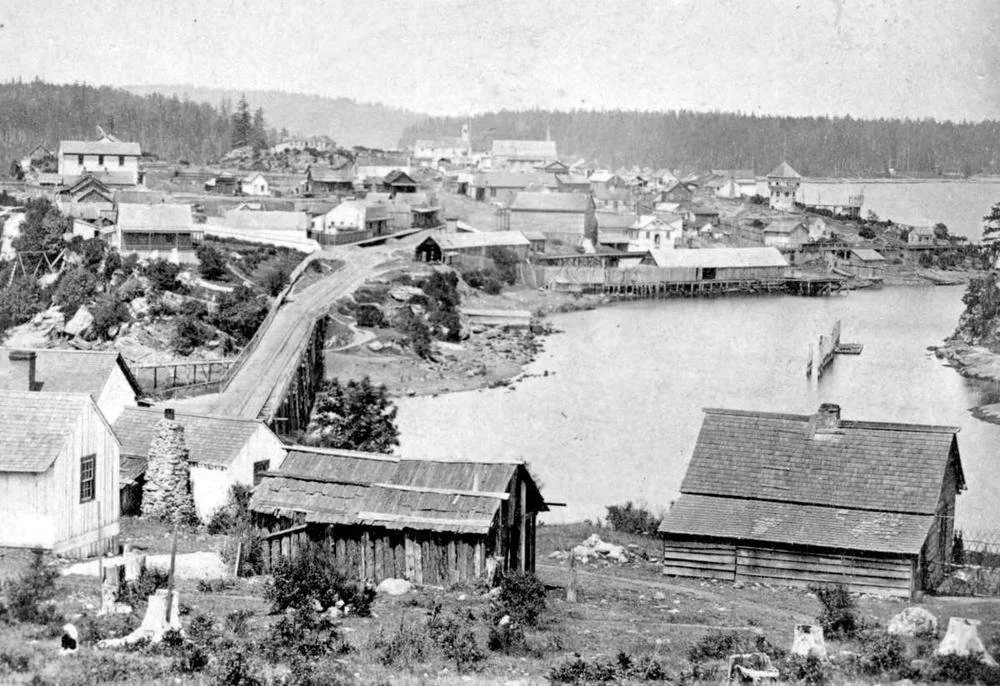

An earlier view of the Nanaimo waterfront; Cameron Island and the Vancouver Coal Co.’s jetty to the right. —BC Archives

Immediately suspected as the cause of the blast was highly volatile coal dust. The fact that the coal was being loaded through chutes meant the unavoidable production of dust. Despite the use of canvas curtains, illumination by open-flame lanterns created the catalyst for disaster.

Upon the dumping of a car containing five tons of coal down the chute, the explosion was described by a survivor as a dull, heavy thud, “as like an earthquake”. Amazingly, the resulting flame flared upward and outward through the forward hatch without causing injury to the ship. It happened in an instant, with a single flash of flame, like that of a lightning bolt.

This was not the way of a gas explosion which, it was thought, would have caused greater damage.

“Another theory advanced,” reported the Press, “was that a giant cartridge [a blasting cap made by the Giant Powder Co.] had been accidentally left [by miners] among the coal and had been fired by the concussion of the [coal falling down the chute], but that is so highly improbable that it is hardly worthy of serious consideration.

Coal was sorted by hand; did an overlooked, live blasting cartidge from the No. 1 Mine ignite the explosion? —Courtesy Matt James

“The fire was a sudden outburst of flame, and in a moment had expended itself. We have made careful inquiries into all the circumstances and surroundings of this unfortunate and mysterious accident, and we draw the following conclusion:

“At the time of the explosion the weather was extremely sultry and oppressive, and that the limited ventilation in the hold and between decks, was almost stagnant, and the air became impregnated with the fine particles of coal dust. The quick rush of about five tons of coal down the shutes [sic] and into the stagnant atmosphere of the between decks, caused a sudden draught, and the impregnated atmosphere was thrown into active commotion and while in this state the dust ignited from one of the several lamps hanging about the between decks.

“It is now a well-established fact that not only will the coal dust in mines, but the dust in flour mills, explode.

“The preventative for such explosions is good ventilation, and we feel confident that the explosion of Thursday was caused solely by the oppressive atmosphere causing the limited ventilation to stagnate, and the use of ordinary ship lamps...”

The Nanaimo waterfront would have looked like this in 1886, as sailing and steam ships waited to load coal, usually without incident. —Vancouver City Archives

Already, despite four doctors and nine nurses working around the clock, some of the worst injured had succumbed to shock. First to die, the next afternoon, was longshoreman William 'Frenchy' Robee who, although a resident of Seattle, was interred in the city cemetery. He was followed, hours later, in death and in interment, by fellow Seattle stevedores James Kade, aged 30, and Hans Hanson, 21.

On Monday morning, four days after the explosion, August Johnson, a 28-year-old seaman on the Pacific, joined the death toll. This left six longshoremen and seamen in hospital with life- threatening injuries.

Because government-appointed medical officer Dr. Cluness doubled as coroner, between attending to victims' medical needs, he chaired the first inquest, that of William Robee. Three further inquests, those for James (since corrected to William) Kade, Hans Hanson and August Johnson followed. In every case, Dr. Benwick cited nervous shock because of extensive skin burns as the killer, none of the victims having demonstrated internal injuries through inhalation.

(With the limited medical capabilities of the day, we can’t even begin to imagine the pain and suffering these men endured; surely, for some, death came as a blessing.)

By the ninth day, those still being treated were said to be having “a severe time of it,” some of them in such extreme pain that they had to be forcibly held down in their beds. Perhaps mercifully, next to go were Patrick Priestly, George Watch and Henry Jackson, all said to have succumbed to nervous shock. Sadly for Jackson, his “good heart and strong constitution” appear to have prolonged his agony.

As the deaths mounted, one of the series of inquests took a curious turn.

At each inquiry, the doctors had extolled the exemplary care and attention given to the patients by themselves and the nurses. But, during the Jackson inquest, male nurse Richard Williams, in answer to a question from a juryman, replied, “So far as I have been on the day shift the doctors and nurses have done their duty; I never saw Dr. Davis, who was on the day shift, take a drink of liquor while on duty. Dr. Cluness is now attending to the patients. Again, to the jury: “I can't say that I saw Dr. Renwick the worse for liquor.”

To the coroner, Dr. Cluness: “[I] never saw Dr. Cluness take a glass of liquor in my life, nor have I seen him under the influence of liquor during my stay at the hospital.”

That's as much as we know from this line of questioning in the reports in the Nanaimo Free Press. But one has to wonder at the fact that, just weeks later, the newspaper reported that Dr. Cluness had died suddenly—of, as it was determined by autopsy, cirrhosis of the liver!

Another view of the coal wharf, taken some years after the accident that claimed the lives of six longshoremen. —BC Archives

To date, the death toll stood at six Seattle longshoremen—William Robee, William Kade, Hans Hanson, Patrick Priestly, August Johnson, William McDonald (originally identified as John Macdonald), Henry Jackson, a seaman of the Queen of the Pacific, and George Watch of Nanaimo. Recovering were the ship's first assistant engineer, William Allison, water tender Richard Parle and seaman James Coffee.

At the official inquiry, held a month later, Allison and Parle testified, but Coffee remained hospitalized and, it seems, had no memory of the accident other than of his being burned. Luckily for Allison, he'd been out of the direct line of fire and his injuries were the least serious. Parle, who said he was the first hit by the blast, thought that it was Allison's lantern, an ordinary lamp such as used in a home, that sparked the blast.

Vancouver Coal Company manager Samuel Robins deposed that he'd been assured by the ship's officers that naked-flame lamps weren't used below decks while loading coal, and that smoking was forbidden.

He said that he was confident that the coal dust had ignited because an un-detonated charge left in the coal would have created two explosions—its own, and that of the coal dust. Professional colliery manager John Bryden concurred, although he didn't attribute the blast to Allison's lantern because “the flame came to him, struck him and knocked him backwards”.

VLC loading manager Harry Cooper testified that the Pacific was one of the best ventilated ships in the trade, that “there was no more than the usual amount of dust for the summertime; it was very hot but there was a slight breeze”. He said that longshoreman Hanson assured him that they'd used only covered lights, but he was convinced that the explosion was caused by an open flame, as was the general practice aboard sailing ships: “Have heard it said that the men smoke in the hold”.

Dr. William Renwick testified that the first three deaths were the result of shock, the rest from “inflammation of the internal organs, particularly the brain”. He made the grim observation that the men's shirts had been “burnt to a tinder”.

Coal Trimmer James Lawrence said he’d seen no naked lights, although it was common practice to use them, but he had noticed “one man especially, smoking”. He initially thought that the ship's boiler had exploded and that there had been a second flash of flame. The final witness, coal trimmer William Crowe, also thought that the boiler had “bursted”. He'd noticed an open-flame lamp burning that morning and, on a previous shift, he'd observed another trimmer and a ship's officer smoking between decks.

Despite the need for ventilation, two of the ship's portholes had been ordered closed, he said.

A month after the disaster, the victims’ suffering went on, the Nanaimo hospital board having to appeal to the public for old cotton and linen rags for bandages—”the great number of patients suffering from burns having entirely exhausted the previous kind donation”. Worse than that, with only four of the injured men having any form of medical coverage, the hospital had been beggared; in mid-September a fund raising benefit was staged in Wellington to raise additional operating funds.

As it happened, the Pacific Coast Steamship Company, owners of the Queen of the Pacific, came through with a cheque for $2002 and a warm thank-you for the hospital's care and attention given its injured seamen.

Local citizens were startled to hear that the Tacoma Ledger had quoted an informant, identified only as “one who knew,” to the effect that it really was a miner's un-exploded cartridge left in the coal that did the damage, But the Free Press held fast to its belief that an explosion other than one caused by coal dust would have caused considerably greater injury to the men and damage to the ship.

All the while, for nine torturous weeks, seaman James Coffee had held on, finally succumbing, the doctors said, to exhaustion. They'd wanted to amputate his right arm but didn't think him strong enough to survive the operation. Dr. Renwick thought he'd survived so long, despite having a preexisting medical condition, because of his strength and “recuperative power”.

The final inquest concluded with Dr. W.N. Jones graphically detailing the horrendous extent of the injuries suffered by Patrick Priestly.

Nanaimo Cemetery. Although from Seattle, three of the stevedores—William ‘Frency’ Robee, Wrilliam Kade and Hans Hanson—are interred here. —Find A Grave

The six longshoremen weren't forgotten by their co-workers of the Stevedores, Longshoremen & Riggers Union of Washington, W.T. who, within weeks, established a memorial in Nanaimo, and expressed their gratitude for the kindnesses shown them: “We wish to express our heartfelt thanks and appreciation of the services rendered our six comrades...

“Should the opportunity ever present itself, the people of Nanaimo may rest assured that the longshoremen of Seattle will endeavour to repay the debt that they so justly owe them.”

The memorial was rededicated in September 2014 by the International Longshoremen Warehouse Local 19 and the Seattle Pension Club.

(With thanks to Ken Hiebert of Ladysmith who kindly reminded me of this tragedy it upon the re-dedication of the memorial.)